Atari 2600

| |

Four-switch VCS model (1980–1982) | |

| Also known as | Atari Video Computer System (prior to November 1982) |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Atari, Inc. |

| Type | Home video game console |

| Generation | Second |

| Release date | |

| Lifespan | 1977–1992 |

| Introductory price | US$189.95 (equivalent to $960 in 2023) |

| Discontinued | 1992[1] |

| Units sold | 30 million (as of 2004[update])[2] |

| Media | ROM cartridge |

| CPU | 8-bit MOS Technology 6507 @ 1.19 MHz |

| Memory | 128 bytes RAM |

| Graphics | Television Interface Adaptor |

| Controller input |

|

| Best-selling game | Pac-Man, 8 million (as of 1990)[a] |

| Predecessor | Atari Home Pong Atari Video Pinball |

| Successor | Atari 5200 |

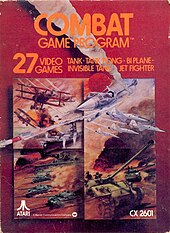

The Atari 2600 is a home video game console developed and produced by Atari, Inc. Released in September 1977 as the Atari Video Computer System (Atari VCS), it popularized microprocessor-based hardware and games stored on swappable ROM cartridges, a format first used with the Fairchild Channel F in 1976. The VCS was bundled with two joystick controllers, a conjoined pair of paddle controllers, and a game cartridge—initially Combat[3] and later Pac-Man.[4] Sears sold the system as the Tele-Games Video Arcade. Atari rebranded the VCS as the Atari 2600 in November 1982, alongside the release of the Atari 5200.

Atari was successful at creating arcade video games, but their development cost and limited lifespan drove CEO Nolan Bushnell to seek a programmable home system. The first inexpensive microprocessors from MOS Technology in late 1975 made this feasible. The console was prototyped under the codename Stella by Atari subsidiary Cyan Engineering. Lacking funding to complete the project, Bushnell sold Atari to Warner Communications in 1976.

The Atari VCS launched in 1977 with nine games on 2 KB cartridges. Atari ported many of their arcade games to the system, and the VCS versions of Breakout and Night Driver are in color while the arcade originals have monochrome graphics. The system's first killer application was the home conversion of Taito's Space Invaders in 1980. Adventure, also released in 1980, was one of the first action-adventure video games and contains the first widely recognized Easter egg. Beginning with the VCS version of Asteroids in 1980, many games used bank switching to allow 8 KB or larger cartridges. By the time of the system's peak in 1982-3, games were released with significantly more advanced visuals and gameplay than the system was designed for, such as Activision's Pitfall!. The popularity of the VCS led to the founding of Activision and other third-party game developers and competition from the Intellivision and, later, ColecoVision consoles.

By 1982, the Atari 2600 was the dominant game system in North America. However, poor decisions by Atari management damaged both the system and company's reputation, most notably the release of two highly anticipated games for the 2600: a port of the arcade game Pac-Man and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Pac-Man became the 2600's bestselling game, but was panned for being inferior to the arcade version. E.T. was rushed to market for the holiday shopping season and was similarly disparaged. Both games, and a glut of third-party shovelware, were factors in ending Atari's significance in the console market, contributing to the video game crash of 1983.

Warner sold the assets of Atari's consumer electronics division to former Commodore CEO Jack Tramiel in 1984. In 1986, the new Atari Corporation under Tramiel released a revised, low-cost 2600 model, and the backward-compatible Atari 7800, but it was Nintendo that led the recovery of the industry with its 1985 launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System. Production of the Atari 2600 ended in 1992, with an estimated 30 million units sold across its lifetime.

History

[edit]| 1972 | Formation of Atari, Inc. |

|---|---|

| 1973 | |

| 1974 | Acquisition of Cyan Engineering |

| 1975 | Debut of the MOS 6502 |

| 1976 | Sale of Atari to Warner Communications |

| 1977 | Launch of Atari VCS |

| 1978 | |

| 1979 | Formation of Activision |

| 1980 | Release of Space Invaders and Adventure |

| 1981 | First bank-switched game: Asteroids |

| 1982 | Rebranding to Atari 2600 (November) |

| Release of Pac-Man and E.T. | |

| 1983 | Video game crash of 1983 |

| 1984 | Sale of Atari to Jack Tramiel |

| 1985 | |

| 1986 | Release of US$50 model |

| 1987 | |

| 1988 | |

| 1989 | |

| 1990 | Final game from Atari: Klax |

| 1991 | |

| 1992 | Discontinuation |

Atari, Inc. was founded by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney in 1972. Its first major product was Pong, released in 1972, the first successful coin-operated video game.[5] While Atari continued to develop new arcade games in following years, Pong gave rise to a number of competitors to the growing arcade game market. The competition along with other missteps by Atari led to financial problems in 1974, though recovering by the end of the year.[6] By 1975, Atari had released a Pong home console, competing against Magnavox, the only other major producer of home consoles at the time. Atari engineers recognized, however, the limitation of custom logic integrated onto the circuit board, permanently confining the whole console to only one game.[7] The increasing competition increased the risk, as Atari had found with past arcade games and again with dedicated home consoles. Both platforms are built from integrating discrete electro-mechanical components into circuits, rather than programmed as on a mainframe computer. Thus, development of a console had cost at least $100,000 (equivalent to about $566,000 in 2023) plus time to complete, but the final product only had about a three-month shelf life until becoming outdated by competition.[6]

By 1974, Atari had acquired Cyan Engineering, a Grass Valley electronics company founded by Steve Mayer and Larry Emmons, both former colleagues of Bushnell and Dabney from Ampex, who helped to develop new ideas for Atari's arcade games. Even before the release of the home version of Pong, Cyan's engineers, led by Mayer and Ron Milner, had envisioned a home console powered by new programmable microprocessors capable of playing Atari's current arcade offerings. The programmable microprocessors would make a console's design significantly simpler and more powerful than any dedicated single-game unit.[8] However, the cost $100–300 of such chips was far outside the range that their market would tolerate.[7] Atari had opened negotiations to use Motorola's new 6800 in future systems.[9]

MOS Technology 6502/6507

[edit]In September 1975, MOS Technology debuted the 6502 microprocessor for $25 at the Wescon trade show in San Francisco.[10][8] Mayer and Milner attended, and met with the leader of the team that created the chip, Chuck Peddle. They proposed using the 6502 in a game console, and offered to discuss it further at Cyan's facilities after the show.[9]

Over two days, MOS and Cyan engineers sketched out a 6502-based console design by Meyer and Milner's specifications.[11] Financial models showed that even at $25, the 6502 would be too expensive, and Peddle offered them a planned 6507 microprocessor, a cost-reduced version of the 6502, and MOS's RIOT chip for input/output. Cyan and MOS negotiated the 6507 and RIOT chips at $12 a pair.[9][12] MOS also introduced Cyan to Microcomputer Associates, who had separately developed debugging software and hardware for MOS, and had developed the JOLT Computer for testing the 6502, which Peddle suggested would be useful for Atari and Cyan to use while developing their system.[8] Milner was able to demonstrate a proof-of-concept for a programmable console by implementing Tank, an arcade game by Atari's subsidiary Kee Games, on the JOLT.[8]

As part of the deal, Atari wanted a second source of the chipset. Peddle and Paivinen suggested Synertek whose co-founder, Bob Schreiner, was a friend of Peddle.[7] In October 1975, Atari informed the market that it was moving forward with MOS. The Motorola sales team had already told its management that the Atari deal was finalized, and Motorola management was livid. They announced a lawsuit against MOS the next week.[9]

Building the system

[edit]

By December 1975, Atari hired Joe Decuir, a recent graduate from University of California, Berkeley who had been doing his own testing on the 6502. Decuir began debugging the first prototype designed by Mayer and Milner, which gained the codename "Stella" after the brand of Decuir's bicycle. This prototype included a breadboard-level design of the graphics interface to build upon.[6][8] A second prototype was completed by March 1976 with the help of Jay Miner, who created a chip called the Television Interface Adaptor (TIA) to send graphics and audio to a television.[13] The second prototype included a TIA, a 6507, and a ROM cartridge slot and adapter.[6]

As the TIA's design was refined, Al Alcorn brought in Atari's game developers to provide input on features.[8] There are significant limitations in the 6507, the TIA, and other components, so the programmers creatively optimized their games to maximize the console.[11] The console lacks a framebuffer and requires games to instruct the system to generate graphics in synchronization with the electron gun in the cathode-ray tube (CRT) as it scans across rows on the screen. The programmers found ways to "race the beam" to perform other functions while the electron gun scans outside of the visible screen.[14]

Alongside the electronics development, Bushnell brought in Gene Landrum, a consultant who had just prior consulted for Fairchild Camera and Instrument for its upcoming Channel F, to determine the consumer requirements for the console. In his final report, Landrum suggested a living room aesthetic, with a wood grain finish, and the cartridges must be "idiot proof, child proof and effective in resisting potential static [electricity] problems in a living room environment". Landrum recommended it include four to five dedicated games in addition to the cartridges, but this was dropped in the final designs.[8] The cartridge design was done by James Asher and Douglas Hardy. Hardy had been an engineer for Fairchild and helped in the initial design of the Channel F cartridges, but he quit to join Atari in 1976. The interior of the cartridge that Asher and Hardy designed was sufficiently different to avoid patent conflicts, but the exterior components were directly influenced by the Channel F to help work around the static electricity concerns.[8][15]

Atari was still recovering from its 1974 financial woes and needed additional capital to fully enter the home console market, though Bushnell was wary of being beholden to outside financial sources.> Atari obtained smaller investments through 1975, but not at the scale it needed, and began considering a sale to a larger firm by early 1976. Atari was introduced to Warner Communications, which saw the potential for the growing video game industry to help offset declining profits from its film and music divisions. Negotiations took place during 1976, during which Atari cleared itself of liabilities, including settling a patent infringement lawsuit with Magnavox over Ralph H. Baer's patents that were the basis for the Magnavox Odyssey.[8] In mid-1976, Fairchild announced the Channel F, planned for release later that year, beating Atari to the market.[15]

By October 1976, Warner and Atari agreed to the purchase of Atari for $28 million.[8] Warner provided an estimated $120 million which was enough to fast-track Stella.[6][16] By 1977, development had advanced enough to brand it the "Atari Video Computer System" (VCS) and start developing games.[6]

Launch and success

[edit]

The unit was showcased on June 4, 1977, at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show with plans for retail release in October. The announcement was purportedly delayed to wait out the terms of the Magnavox patent lawsuit settlement, which would have given Magnavox all technical information on any of Atari's products announced between June 1, 1976, and June 1, 1977.[8] However, Atari encountered production problems during its first batch, and its testing was complicated by the use of cartridges.

The Atari VCS was launched in September 1977 at $199 (equivalent to about $1,000 in 2023), with two joysticks and a Combat cartridge; eight additional games were sold separately.[17] Most of the launch games were based on arcade games developed by Atari or its subsidiary Kee Games: for example, Combat was based on Kee's Tank (1974) and Atari's Jet Fighter (1975).[6] Atari sold between 350,000 and 400,000 Atari VCS units during 1977, attributed to the delay in shipping the units and consumers' unfamiliarity with a swappable-cartridge console that is not dedicated to only one game.[18]

In 1978, Atari sold only 550,000 of the 800,000 systems manufactured. This required further financial support from Warner to cover losses.[18] Bushnell pushed the Warner Board of Directors to start working on "Stella 2", as he grew concerned that rising competition and aging tech specs of the VCS would render the console obsolete. However, the board stayed committed to the VCS and ignored Bushnell's advice, leading to his departure from Atari in 1979. Atari sold about 600,000 VCS systems in 1979, bringing the installed base to a little over 1.3 million.[19]

Atari obtained a license from Taito to develop a VCS conversion of its 1978 arcade hit Space Invaders. This is the first officially licensed arcade conversion for a home console.[20] Atari sold 1.25 million Space Invaders cartridges and over 1 million VCS systems in 1980, nearly doubling the install base to over 2 million, and then an estimated 3.1 million VCS systems in 1981.[19] By 1982, 10 million consoles had been sold in the United States, while its best-selling game was Pac-Man[21] at over 8 million copies sold by 1990.[a] Pac-Man propelled worldwide Atari VCS sales to 12 million units during 1982, according to a November 1983 article in InfoWorld magazine.[24] An August 1984 InfoWorld magazine article says more than 15 million Atari 2600 machines were sold by 1982.[25] A March 1983 article in IEEE Spectrum magazine has about 3 million VCS sales in 1981, about 5.5 million in 1982, as well as a total of over 12 million VCS systems and an estimated 120 million cartridges sold.[26]

In Europe, the Atari VCS sold 125,000 units in the United Kingdom during 1980,[27] and 450,000 in West Germany by 1984.[28] In France, where the VCS released in 1982, the system sold 600,000 units by 1989.[29] The console was distributed by Epoch Co. in Japan in 1979 under the name "Cassette TV Game", but did not sell as well as Epoch's own Cassette Vision system in 1981.[30]

In 1982, Atari launched its second programmable console, the Atari 5200. To standardize naming, the VCS was renamed to the "Atari 2600 Video Computer System", or "Atari 2600", derived from the manufacture part number CX2600.[31] By 1982, the 2600 cost Atari about $40 to make and was sold for an average of $125 (equivalent to $390 in 2023). The company spent $4.50 to $6 to manufacture each cartridge, plus $1 to $2 for advertising, wholesaling for $18.95 (equivalent to $60 in 2023).[24]

Third-party development

[edit]Activision, formed by Crane, Whitehead, and Miller in 1979, started developing third-party VCS games using their knowledge of VCS design and programming tricks and began releasing games in 1980. Kaboom! (1981) and Pitfall! (1982) are among the most successful with at least one and four million copies sold, respectively.[32] In 1980, Atari attempted to block the sale of the Activision cartridges, accusing the four of intellectual property infringement. The two companies settled out of court, with Activision agreeing to pay Atari a licensing fee for their games. This made Activision the first third-party video game developer and established the licensing model that continues to be used by console manufacturers for game development.[33]

Activision's success led to the establishment of other third-party VCS game developers following Activision's model in the early 1980s,[34][35][36] including U.S. Games, Telesys, Games by Apollo, Data Age, Zimag, Mystique, and CommaVid. The founding of Imagic included ex-Atari programmers. Mattel and Coleco, each already producing its own more advanced console, created simplified versions of their existing games for the 2600. Mattel used the M Network brand name for its cartridges. Third-party games accounted for half of VCS game sales by 1982.[37]

Decline and redesign

[edit]In addition to third-party game development, Atari also received the first major threat to its hardware dominance from the ColecoVision. Coleco had a license from Nintendo to develop a version of the arcade game Donkey Kong (1981), which was bundled with every ColecoVision console. Coleco gained about 17% of the hardware market in 1982 compared to Atari's 58%.[38] With third parties competing for market share, Atari worked to maintain dominance in the market by acquiring licenses for popular arcade games and other properties to make games from. Pac-Man has numerous technical and aesthetic flaws, but nevertheless more than 7 million copies were sold. Heading into the 1982 holiday shopping season, Atari had placed high sales expectations on E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, a game programmed in about six weeks. Atari produced an estimated four million cartridges,[39] but the game was poorly reviewed, and only about 1.5 million units were sold.[40]

Warner Communications issued revised earnings guidance in December 1982 to its shareholders, having expected a 50% year-to-year growth but now only expecting 10–15% due to declining sales at Atari.[41][42] Coupled with the oversaturated home game market, Atari's weakened position led investors to start pulling funds out of video games, beginning a cascade of disastrous effects known as the video game crash of 1983.[41] Many of the third-party developers formed prior to 1983 were closed, and Mattel and Coleco left the video game market by 1985.[43]

In September 1983, Atari sent 14 truckloads of unsold Atari 2600 cartridges and other equipment to a landfill in the New Mexico desert, later labeled the Atari video game burial.[44] Long considered an urban legend that claimed the burial contained millions of unsold cartridges, the site was excavated in 2014, confirming reports from former Atari executives that only about 700,000 cartridges had actually been buried.[45] Atari reported a $536 million loss for 1983 as a whole,[46]: ch14 and continued to lose money into 1984, with a $425 million loss reported in the second quarter.[47] By mid-1984, software development for the 2600 had essentially stopped except that of Atari and Activision.[48]

Warner, wary of supporting its failing Atari division, started looking for buyers in 1984. Warner sold most of the assets of Atari's counsumer electronics and home computer divisions to Jack Tramiel, the founder of Commodore International, in July 1984 in a deal valued at $240 million, though Warner retained Atari's arcade business. Tramiel was a proponent of personal computers, and halted all new 2600 game development soon after the sale.[47]

The North American video game market did not recover until about 1986, after Nintendo's 1985 launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in North America. Atari Corporation released a redesigned model of the 2600 in 1986, supported by an ad campaign touting a price of "under 50 bucks".[49] With a large library of cartridges and a low price point, the 2600 continued to sell into the late 1980s. Atari released the last batch of games in 1989–90 including Secret Quest[50] and Fatal Run.[51] By 1986, over 20 million Atari VCS units had been sold worldwide.[52][53] The final Atari-licensed release is the PAL-only version of the arcade game KLAX in 1990.

After more than 14 years on the market, 2600 production ended in 1992,[1] along with the Atari 7800 and Atari 8-bit computers. In Europe, last stocks of the 2600 were sold until Summer/Fall of 1995.[54]

Hardware

[edit]Console

[edit]The Atari 2600's CPU is the MOS Technology 6507, a version of the 6502,[55] running at 1.19 MHz in the 2600.[56] Though their internal silicon was identical, the 6507 was cheaper than the 6502 because its package included fewer memory-address pins—13 instead of 16.[57] The designers of the Atari 2600 selected an inexpensive cartridge interface[58] that has one fewer address pins than the 13 allowed by the 6507, further reducing the already limited addressable memory from 8 KB (213 = 8,192) to 4 KB (212 = 4,096). This was believed to be sufficient as Combat was only 2 KB.[59] Later games circumvented this limitation with bank switching.[60]

The console has 128 bytes of RAM for scratch space, the call stack, and the state of the game environment.

The top bezel of the console originally had six switches: power, TV type selection (color or black-and-white), game selection, left and right player difficulty, and game reset. The difficulty switches were moved to the back of the bezel in later versions of the console. The back bezel also included the controller ports, TV output, and power input.

Graphics

[edit]

The Atari 2600 was designed to be compatible with the cathode-ray tube television sets produced in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which commonly lack auxiliary video inputs to receive audio and video from another device. Therefore, to connect to a TV, the console generates a radio frequency signal compatible with the regional television standards (NTSC, PAL, or SECAM), using a special switch box to act as the television's antenna.[62][11]

Atari developed the Television Interface Adaptor (TIA) chip in the VCS to handle the graphics and conversion to a television signal. It provides a single-color, 20-bit background register that covers the left half of the screen (each bit represents 4 adjacent pixels) and is either repeated or reflected on the right side. There are 5 single-color sprites: two 8-pixel wide players; two 1 bit missiles, which share the same colors as the players; and a 1-pixel ball, which shares the background color. The 1-bit sprites all can be controlled to stretch to 1, 2, 4, or 8 pixels.[63]

The system was designed without a frame buffer to avoid the cost of the associated RAM. The background and sprites apply to a single scan line, and as the display is output to the television, the program can change colors, sprite positions, and background settings. The careful timing required to sync the code to the screen on the part of the programmer was labeled "racing the beam"; the actual game logic runs when the television beam is outside of the visible area of the screen.[64][14] Early games for the system use the same visuals for pairs of scan lines, giving a lower vertical resolution, to allow more time for the next row of graphics to be prepared. Later games, such as Pitfall!, change the visuals for each scan line or extend the black areas around the screen to extend the game code's processing time.[32][61]

Regional releases of the Atari 2600 use modified TIA chips for each region's television formats, which require games to be developed and published separately for each region. All modes are 160 pixels wide. NTSC mode provides 192 visible lines per screen, drawn at 60 Hz, with 16 colors, each at 8 levels of brightness. PAL mode provides more vertical scanlines, with 228 visible lines per screen, but drawn at 50 Hz and only 13 colors. SECAM mode, also a 50 Hz format, is limited to 8 colors, each with only a single brightness level.[63][65]

Controllers

[edit]The first VCS bundle has two types of controllers: a joystick (part number CX10) and pair of rotary paddle controllers (CX30). Driving controllers, which are similar to paddle controllers but can be continuously rotated, shipped with the Indy 500 launch game. After less than a year, the CX10 joystick was replaced with the CX40 model[66] designed by James C. Asher.[67] Because the Atari joystick port and CX40 joystick became industry standards, 2600 joysticks and some other peripherals work with later systems, including the MSX, Commodore 64, Amiga, Atari 8-bit computers, and Atari ST. The CX40 joystick can be used with the Master System and Sega Genesis, but does not provide all the buttons of a native controller. Third-party controllers include Wico's Command Control joystick.[68] Later, the CX42 Remote Control Joysticks, similar in appearance but using wireless technology, were released, together with a receiver whose wires could be inserted in the controller jacks.[69]

Atari introduced the CX50 Keyboard Controller in June 1978 along with two games that require it: Codebreaker and Hunt & Score.[66] The similar, but simpler, CX23 Kid's Controller was released later for a series of games aimed at a younger audience.[70] The CX22 Trak-Ball controller was announced in January 1983 and is compatible with the Atari 8-bit computers.[71]

There were two attempts to turn the Atari 2600 into a keyboard-equipped home computer: Atari's never-released CX3000 "Graduate" keyboard,[72] and the CompuMate keyboard by Spectravideo which was released in 1983.[73]

Console models

[edit]Minor revisions

[edit]The initial production of the VCS was made in Sunnyvale during 1977, using thick polystyrene plastic for the casing as to give the impression of weight from what was mostly an empty shell inside.[8] The initial Sunnyvale batch had also included potential mounts for an internal speaker system on the casing, though the speakers were found to be too expensive to include; instead sound was routed through the TIA to the connected television.[8] All six console switches were mounted on the front panel. Production of the unit was moved to Taiwan in 1978, where a less thick internal metal shielding was used and thinner plastic was used for the casing, reducing the system's weight. These two versions are commonly referred to as "Heavy Sixers" and "Light Sixers" respectively, referencing the six front switches.[74][8]

In 1980, the difficulty switches were moved to the back of the console, leaving four switches on the front and replacing the previous all lowercase font for the switch labels to fully capitalized wording. Otherwise, these four-switch consoles look nearly identical to the earlier six-switch models. In 1982, to coincide with the release of the Atari 5200, Atari rebranded the console as the "Atari 2600", a name first used on a version of the four-switch model without woodgrain, giving it an all-black appearance. This all-black model is commonly referred to by fans as the "Vader" model, due to its resemblance to the Star Wars character of the same name.

Sears Video Arcade

[edit]Atari continued its OEM relationship with Sears under the latter's Tele-Games brand, which started in 1975 with the original Pong. This is unrelated to the company Telegames, which later produced 2600 cartridges.[75][76] Sears released several models of the VCS as the Sears Video Arcade series starting in 1977. The final Sears-specific model was the Video Arcade II, released during the fall of 1982.[77]

Sears released versions of Atari's games with Tele-Games branding, usually with different titles.[78] Three games were produced by Atari for Sears as exclusive releases: Steeplechase, Stellar Track, and Submarine Commander.[78]

Atari 2800

[edit]The Atari 2800 is the Japanese version of the 2600 released in October 1983. It is the first Japan-specific release of a 2600, though companies like Epoch had distributed the 2600 in Japan previously. The 2800 was released a short time after Nintendo's Family Computer (which became the dominant console in Japan), and it did not gain a significant share of the market. Sears previously released the 2800 in the US during late 1982 as the Sears Video Arcade II, which came packaged with two controllers and Space Invaders.[79][77] Around 30 specially branded games were released for the 2800.

Designed by engineer Joe Tilly, the 2800 has four controller ports instead of the two of the 2600. The controllers are an all-in one design using a combination of an 8-direction digital joystick and a 270-degree paddle, designed by John Amber.[79] The 2800's case design departed from the 2600, using a wedge shape with non-protruding switches. The case style is the basis for the Atari 7800, which was redesigned for the 7800 by Barney Huang.[79]

1986 model

[edit]The cost-reduced 1986 model, sometimes referred to as the "2600 Jr.", has a smaller form factor with an Atari 7800-like appearance. It was advertised as a budget gaming system (under $50) with the ability to run a large collection of games.[80] Released after the video game crash of 1983, and after the North American launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System, the 2600 was supported with new games and television commercials promoting "The fun is back!". Atari released several minor stylistic variations: the "large rainbow" (shown), "short rainbow", and an all-black version sold only in Ireland.[81] Later European versions include a joypad.[82]

Unreleased prototypes

[edit]The Atari 2700 was a version of the 2600 with wireless controllers.

The CX2000, with integrated joystick controllers, was a redesign based on human factor analysis by Henry Dreyfuss Associates.[83]

The circa-1982 Atari 3200 was a backwards compatible 2600 successor with "more memory, higher resolution graphics and improved sound".[84]

Related hardware and recreations

[edit]The Atari 7800, announced in 1984 and released in 1986, is the official successor to the Atari 2600 and is backward compatible with 2600 cartridges.

Multiple retro-style consoles and microconsoles have been released since the lifespan of the original Atari 2600:

- The TV Boy includes 127 games in an enlarged joypad.

- The Atari Classics 10-in-1 TV Game, manufactured by Jakks Pacific, emulates the 2600 with ten games inside an Atari-style joystick with composite-video output.

- The Atari Flashback 2 (2005) contains 40 games, with four additional programs unlocked by a cheat code. It uses a recreated chip based on original 2600 hardware, and is compatible with original 2600 controllers. It can be modified to play original 2600 cartridges.

- In 2017, Hyperkin announced the RetroN 77, a clone of the Atari 2600 that plays original cartridges instead of preinstalled games.[85]

- The Atari VCS (2021 console) can download and emulate 2600 games via an online store.[86]

- The Atari Flashback 12 Gold (2023) contains 130 games built-in.[87]

- The Atari 2600+ (2023) is a replica of the 2600 and is 20% smaller. The 2600+ includes support for original Atari 2600 and 7800 cartridges.[88]

- The Atari 7800+ (2024) is a smaller replica of the Atari 7800. It has similar features to the Atari 2600+, but its exterior encasing design pays homage to the Atari 7800.

Games

[edit]In 1977, nine games were released on cartridge to accompany the launch of the console: Air-Sea Battle, Basic Math, Blackjack, Combat, Indy 500, Star Ship, Street Racer, Surround, and Video Olympics.[89] Indy 500 shipped with special "driving controllers", which are like paddles but rotate freely. Street Racer and Video Olympics use the standard paddle controllers. Atari, Inc. was the only developer for the first few years, releasing dozens of games.

Atari determined that box art featuring only descriptions of the game and screenshots would not be sufficient to sell games in retail stores, since most games were based on abstract principles and screenshots give little information. Atari outsourced box art to Cliff Spohn, who created visually interesting artwork with implications of dynamic movement intended to engage the player's imagination while staying true to the gameplay. Spohn's style became a standard for Atari when bringing in assistant artists, including Susan Jaekel, Rick Guidice, John Enright, and Steve Hendricks.[90] Spohn and Hendricks were the largest contributors to the covers in the Atari 2600 library. Ralph McQuarrie, a concept artist on the Star Wars series, was commissioned for one cover, the arcade conversion of Vanguard.[91] These artists generally conferred with the programmer to learn about the game before drawing the art.[90]

An Atari VCS port of the Breakout arcade game appeared in 1978. The original is in black and white with a colored overlay, and the home version is in color. In 1980, Atari released Adventure,[92] the first action-adventure game, and the first home game with a hidden Easter egg.

Rick Maurer's port of Taito's Space Invaders, released in 1980, is the first VCS game to have more than one million copies sold—eventually doubling that[93] within a year[94] and totaling more than 6 million cartridges by 1983.[22] It became the killer app to drive console sales. Versions of Atari's own Asteroids and Missile Command arcade games, released in 1981, were also major hits.

Each early VCS game is in a 2K ROM. Later games, like Space Invaders, have 4K.[95] The VCS port of Asteroids (1981) is the first game for the system to use 8K via a bank switching technique between two 4K segments.[96] Some later releases, including Atari's ports of Dig Dug and Crystal Castles, are 16K cartridges.[95] One of the final games, Fatal Run (1990), doubled this to 32K.[97]

Many early VCS titles were able to display in both monochrome (black and white) and full color through the use of the "TV type" switch on the console. This allowed the VCS games to function on both monochrome and color televisions. However, beginning around the rebranding from "VCS" to "2600", support for black and white display modes diminished greatly, with most releases during this period only displaying in color and the TV type switch serving no function. Other later titles, such as Secret Quest, began using the TV type switch for gameplay functions, such as pausing.[98]

Two Atari-published games, both from the system's peak in 1982, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial[99] and Pac-Man,[100] are cited as factors in the video game crash of 1983.

A company named American Multiple Industries produced a number of pornographic games for the 2600 under the Mystique Presents Swedish Erotica label. The most notorious, Custer's Revenge, was protested by women's and Native American groups[101] because it depicted General George Armstrong Custer raping a bound Native American woman.[102] Atari sued American Multiple Industries in court over the release of the game.[103]

Legacy

[edit]

The 2600 was so successful in the late 1970s and early 1980s that "Atari" was a synonym for the console in mainstream media and for video games in general.[104] Jay Miner directed the creation of the successors to the 2600's TIA chip—CTIA and ANTIC—which are central to the Atari 8-bit computers released in 1979 and later the Atari 5200 console.

The Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame at The Strong in Rochester, New York, in 2007.[105] In 2009, the Atari 2600 was named the number two console of all time by IGN, which cited its remarkable role behind both the first video game boom and the video game crash of 1983, and called it "the console that our entire industry is built upon".[106]

In November 2021, the current incarnation of Atari announced three 2600 games to be published under "Atari XP" label: Yars' Return, Aquaventure, and Saboteur.[107] These were previously included in Atari Flashback consoles.[108]

A model of the Atari 2600 was released by Lego in 2022.[109] Included are the three games Asteroid, Centipede, and Adventure. Included is a minifigure with a bedroom designed from the 1980s.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Montfort & Bogost 2009, p. 137.

- ^ "A Brief History of Game Console Warfare". BusinessWeek. May 9, 2007. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ Weesner, Jason (January 11, 2007). "On Game Design: A History of Video Games". Archived from the original on November 24, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "Image of box with Pac-Man sticker". Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Chafkin, Max (April 1, 2009). "Nolan Busnell is Back in the Game". Inc. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fulton, Steve (November 6, 2007). "The History of Atari: 1971–1977". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c Goldberg, Marty (January 4, 2008). "The 2600 Story – Part I". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Goldberg, Marty; Vendel, Curt (2012). "Chapter 5". Atari Inc: Business is Fun. Sygyzy Press. ISBN 978-0985597405.

- ^ a b c d Bagnall, Brian (2011). Commodore: A company on the edge. Variant Press. ISBN 978-0973864960.

- ^ "MOS 6502 the second of a low cost high performance microprocessor family". Computer. 8 (9). IEEE Computer Society: 38–39. September 1975. doi:10.1109/C-M.1975.219074. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c Decuir, Joe (July 2015). "Atari Video Computer System: Bring Entertainment Stories Home". IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine: 59–66. doi:10.1109/MCE.2015.2421572.

- ^ Oral History of Chuck Peddle. Computer History Museum X7180.2014 https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102739938 Archived June 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enHF9lMseP8 Archived June 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine time index: 0:59:10 and 1:19:24

- ^ Curt Vendel. "The Atari VCS Prototype". Atarimuseum.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Kohler, Chris (March 19, 2009). "Racing the Beam: How Atari 2600's Crazy Hardware Changed Game Design". Wired. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Edwards, Benj (January 22, 2015). "The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge". Fast Company. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Goll, Steve (October 1, 1984). "When The Magic Goes". Inc. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Forster, Winnie (2005). The encyclopedia of consoles, handhelds & home computers 1972–2005. GAMEPLAN. p. 27. ISBN 3-00-015359-4.

- ^ a b Fulton, Steve (August 21, 2008). "Atari: The Golden Years – A History, 1978–1981". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Smith, Alexander (2019). They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Vol I (1 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 458, 466, 518. ISBN 9781138389908.

- ^ "The Definitive Space Invaders". Retro Gamer. No. 41. Imagine Publishing. September 2007. pp. 24–33.

- ^ Guinness World Records Gamer's Edition. Guinness World Records. 2008. p. 24. ISBN 1-904994-21-0.

10 million – number of Atari 2600 consoles sold by 1982.

- ^ a b Cartridge Sales Since 1980. Atari Corp. Via "The Agony & The Ecstasy". Once Upon Atari. Episode 4. Scott West Productions. August 10, 2003. 23 minutes in.

- ^ Vendel, Curt (May 28, 2009). "Site News". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Hubner, John; Kistner, William F. (November 28, 1983). "The Industry: What went wrong at Atari?". InfoWorld. Vol. 5, no. 48. InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. pp. 151–158 (157). ISSN 0199-6649. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ Bisson, Gisselle (August 6, 1984). "Atari: From Starting Black to Auction Block". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 32. InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. p. 52. ISSN 0199-6649.

- ^ Perry, Tekla; Wallich, Paul (March 1983). "Design case history: the Atari Video Computer System". IEEE Spectrum. 20 (3): 45, 50, 51. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.1983.6369841. S2CID 2840318.

- ^ "Technology: The games that aliens play". New Scientist. Vol. 88, no. 1232–1233. Reed Business Information. December 18, 1980. p. 782. ISSN 0262-4079.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "EG Goes Continental: Europe Joins the Game World". Electronic Games. Vol. 2, no. 23. January 1984. pp. 46–7. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "Guerre Dans Le Salon" [War in the Living Room]. Science & Vie Micro (in French). No. 67. December 1989. pp. 126–8. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "40 years of the Nintendo Famicom – the console that changed the games industry | Games | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ Barton, Matt; Loguidice, Bill (February 28, 2008). "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 2600 Video Computer System/VCS". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Reeves, Ben (February 26, 2013). "Activisionaries: How Four Programmers Changed The Game Industry". Game Informer. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Flemming, Jeffrey. "The History Of Activision". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ "Atari Sues to k.o. Competition". InfoWorld. Vol. 2, no. 13. August 4, 1980. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ John Markoff (December 21, 1981). "Atari attempts to gobble software competition". InfoWorld. Vol. 3, no. 31. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Mark P. Wolf (2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 6. ISBN 9780313379369. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Rosenberg, Ron (December 11, 1982). "Competitors Claim Role in Warner Setback". The Boston Globe. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ Gallager, Scott; Ho Park, Seung (February 2002). "Innovation and Competition in Standard-Based Industries: A Historical Analysis of the U.S. Home Video Game Market". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 49 (1). IEEE Technology and Engineering Management Society: 67–82. doi:10.1109/17.985749.

- ^ Bruck, Master of the Game: Steve Ross and the Creation of Time Warner, pp. 179–180

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "IGN: Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ a b Crawford, Chris (1991). "The Atari Years". The Journal of Computer Game Design. Vol. 5.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara; Mikkelson, David P (May 10, 2011). "Buried Atari Cartridges". Snopes.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Ernkvist, Mirko (2008). "Down many times, but still playing the game: Creative destruction and industry crashes in the early video game industry 1971–1986". In Gratzer, Karl; Stiefel, Dieter (eds.). History of Insolvancy and Bankruptcy. Södertörns högskola. pp. 161–191. ISBN 978-91-89315-94-5.

- ^ "Atari Parts Are Dumped". The New York Times. September 28, 1983. Archived from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ Poeter, Damon (May 31, 2014). "Atari's Buried E.T. Games Up for Sale". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- ^ Kent, Steven (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b Sange, David E. (July 3, 1984). "Warner Sells Atari To Tramiel". The New York Times. pp. Late City Final Edition, Section D, Page 1, Column 6, 1115 words. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016.

- ^ Holyoak, Craig (May 30, 1984). "Here are ColecoVision's jewels". Deseret News. pp. 4 WV. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ "Atari 2600 1986 Commercial 'The Fun is Back'". YouTube. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Secret Quest". Atari Mania. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Fatal Run". Atari Mania. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Where every home game turns out to be a winter". The Guardian. March 6, 1986. p. 15. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (September 27, 1986). "Video Games, Once Zapped, In Comeback". The New York Times. A1. Archived from the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Atari Benelux Timeline – Atarimuseum.nl". Archived from the original on May 16, 2023. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "When Pac Ruled the Earth". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 62. EGM Media, LLC. September 1994. p. 18.

- ^ Stewart, Keith (February 24, 2017). "10 most influential games consoles – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ Montfort & Bogost 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Montfort & Bogost 2009, p. 26 The cartridge connector's 24 pins are allocated to one supply-voltage line, two ground lines, 8 data lines, and 13 address lines. The uppermost address line is used as a so-called chip select for the cartridge's ROM chip, however, leaving only 12 address lines for the chip's game program. Thus, without special "hardware tricks" built into the cartridge, an Atari 2600 game can occupy a maximum address space of 4 KB.

- ^ Montfort & Bogost 2009, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Montfort & Bogost 2009, p. 88.

- ^ a b Kohler, Chris (March 13, 2009). "Racing the Beam: How Atari 2600's Crazy Hardware Changed Game Design". Wired. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014.

- ^ Arceneaux, Noah (February 19, 2010). "Review Article: Game theories, technologies and techniques of play". New Media & Society. 12 (1): 161–166. doi:10.1177/1461444809350996. S2CID 220595570.

- ^ a b Wright, Steve (December 3, 1979), Stella Programmer's Guide

- ^ Montfort & Bogost 2009.

- ^ Atari 2600 "TIA color chart" Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Current, Michael A. "A History of WCI Games / Atari / Atari Games / Atari Holdings". Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ "United States Patent 4,349,708" (PDF). September 14, 1982. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Hruschak, PJ (April 1, 2008). "Gamertell Review: Wico's Command Control Joystick". Technologytell.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016.

- ^ "AtariAge – Atari 2600 – Controllers – Remote Control Joysticks". atariage.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "AtariAge – Atari 2600 – Controllers – Kid's Controller". atariage.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ Current, Michael D. "Atari 8-Bit Computers FAQ". Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ "The Atari "Graduate" Computer CX-3000". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ "The Spectravideo "Compumate" Keyboard". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on November 26, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ Beaudoin, Dave (May 31, 2016). "You Can Judge a 2600 By Its Cover". Digital Game Museum. Archived from the original on September 11, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ Yarusso, Albert. "Atari 2600 Catalog: Telegames". AtariAge. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- ^ Grasso, Michael (September 19, 2017). "The Sears Tele-Games Video Arcade (1977) and the Coleco Gemini (1982)". We Are the Mutants. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ a b "Sears Ad". Daily Record. Sears. December 8, 1982. p. 9. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Yarusso, Albert. "Atari 2600 – Sears – Picture Label Variation". AtariAge. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c Vendel, Curt. "The Atari 2800 System". atarimuseum.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Atari 7800 and 2600". Sears Catalog. 1988. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "2600 Consoles and Clones". Archived from the original on October 6, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ retroplace. "Atari 2600 Jr. | Atari 2600". retroplace.com. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "The Atari CX-2000 Prototype". www.atarimuseum.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "The Atari 3200: Super-Stella/Sylvia". AtarL Museum. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ "Atari 2600 fans get the revival console they deserve". June 14, 2017. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Bonifac, Igor (June 15, 2021). "Atari VCS is now available to buy". Engadget. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "Atari Flashback 12 Gold Console". AtGames E-Store. Archived from the original on September 16, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ Nam, Michael (September 30, 2023). "Atari 2600+ sees its future in retro gaming | CNN Business". CNN. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ "Video Games Console Library Atari VCS Launch Titles". Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Webster, Andrew (September 19, 2013). "How Atari Box Art Turned 8-bit Games Into Virtual Wonderlands". The Verge. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Wanserski, Nick (February 22, 2017). "How fantastical Atari box art taught the world what makes video games special". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Robinett, Warren. "Adventure for the Atari 2600 Video Game Console". Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ Kevin Day, Patrick (January 22, 2013). "Atari bankruptcy: Remembering the 2600, 7 bestselling games". Hero Complex. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ Hutcheon, Stephen (June 7, 1983). "The video games boom has yet to come". The Age. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Horton, Kevin (1996). "Info about cart sizes and bankswitching methods". Archived from the original on February 23, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Grand, Joe (2004). Hardware Hacking. Syngress Publishing. ISBN 978-1932266832.

- ^ "Atari 2600 VCS Fatal Run : scans, dump, download, screenshots, ads, videos, catalog, instructions, roms". www.atarimania.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Nerdly Pleasures: The Forgotten Switch : The Atari 2600's B&W/Color Switch". Nerdly Pleasures. March 22, 2015. Archived from the original on January 28, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy. "Classic 1UP.Com's Essential 50". 1UP.Com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ Vendel, Curt. "The Atari 2600 Video Computer System". The Atari Museum. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "AGH – Third Party Profile: Mystique". AtariHQ.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Fragmaster. "Custer's Revenge". Classic Gaming. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Gonzalez, Lauren. "When Two Tribes Go to War: A History of Video Game Controversy". GameSpot. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Edgers, Geoff (March 8, 2009). "Atari and the deep history of video games". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ Farhad Manjoo (November 10, 2007). "The Atari 2600 makes the Toy Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ "Atari 2600 is number 2". IGN. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ Gardner, Matt (November 17, 2021). "Atari 2600 Gets Three New Releases, 28 Years After Discontinuation". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Fahey, Mike (November 17, 2021). "Atari's New Collectible Game Cartridges Off To A Rocky Start". Kotaku. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Reed, Chris (August 1, 2022). "Atari 2600 LEGO Set Is Now Available". IGN. Retrieved November 13, 2024.

General bibliography

[edit]- Tim Lapetino (2016). "Industrial Design". Art of Atari. Dynamite. ISBN 978-1-5241-0103-9. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- Montfort, Nick & Bogost, Ian (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- Perry, Tekla; Wallich, Paul (March 1983). "Design case history: The Atari Video Computer System". IEEE Spectrum.

External links

[edit]- A history of the Atari VCS/2600

- Inside the Atari 2600

- Hardware and prototypes at the Atari Museum