Architecture of Albany, New York

The architecture of Albany, New York, embraces a variety of architectural styles ranging from the early 18th century to the present. The city's roots date from the early 17th century and few buildings survive from that era or from the 18th and early 19th century. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 triggered a building boom, which continued until the Great Depression and the suburbanization of the area afterward. This accounts for much of the construction in the city's urban core along the Hudson River. Since then most construction has been largely residential, as the city spread out to its current boundaries, although there have been some large government building complexes in the modernist style, such as Empire State Plaza, which includes the Erastus Corning Tower, the tallest building in New York outside of New York City.[1]

Owing to Albany's status as New York's state capital, many of its most architecturally notable buildings are government buildings, such as the state capitol and city hall. The city also boasts many prominent churches, such as All Saints and Immaculate Conception cathedrals, the diocesan seats of the Episcopal and Roman Catholic churches respectively. Downtown has some prominent commercial buildings like the former headquarters of the Delaware and Hudson Railroad, now the SUNY System Administration Building, another symbol of the city. The bulk of the city's historic architecture, however, are its many rowhouses, homes to residents of both affluent neighborhoods like Center Square and poorer areas like Arbor Hill.

Architects of national stature represented among Albany's buildings include Philip Hooker, Patrick Keely, Andrew Jackson Downing and Calvert Vaux, Richard Upjohn and his son, Henry Hobson Richardson, and Stanford White. In their capacity as New York's state architect, Isaac Perry and Lewis Pilcher did significant work. Two architects who practiced locally, Marcus T. Reynolds and Albert Fuller, contributed many important early 20th-century buildings.

Much of the city's important architecture has been recognized in the city's listings on the National Register of Historic Places, either individually or as contributing properties to its 14 historic districts. All but two of the other 48 extant properties listed are buildings. Three—the state capitol, St. Peter's Episcopal Church and the mansion of Revolutionary War officer and early U.S. Senator Philip Schuyler—are further recognized as National Historic Landmarks in part for their architectural achievement.

Overview

[edit]

Albany is situated along the Hudson River. Its central core is opposite the smaller city of Rensselaer, with which it is connected by the Dunn Memorial Bridge. Major roads—Interstate 787 on the east, the Slingerlands Bypass (New York State Route 85), I-787 and the Interstate 87 portion of the New York State Thruway on the south and Interstate 90 on the north—form the envelope of most of the city's developed area. Beyond the Slingerlands Bypass the city is bounded mostly by Normanskill Creek and its tributary Krum Kill, save for a long western protrusion that encompasses the Albany Pine Bush Preserve.

I-787 and the railroad tracks used by CSX Transportation's River Subdivision separate the industrial waterfront of the Port of Albany and parks like the Corning Preserve from the rest of the city.[2] To the west the land gently rises 200 feet (60 m), giving buildings about a half-mile (800 m) from the riverfront a view of it over the buildings to their east.[3] This bluff was, at the time of original settlement, divided by ravines through which various creeks flowed, ravines which have been mostly filled in as the city grew. Sheridan Hollow, just north of downtown, was an exception as it could not be completely filled and still topographically sets off Arbor Hill and the 82-acre (33 ha) Tivoli Nature Preserve to its north.[4] With the exception of the riverfront portion of the city, Interstate 90 roughly parallels the city's northern boundary with the village of Menands and, further inland, the town of Colonie.

Downtown Albany, the densely developed center of the flood plain area, is the oldest neighborhood in the city, roughly contiguous with the city's original stockaded area. it is densely developed with high-rises like the Home Savings Bank Building, joined by newer projects like the Times Union Center arena.[5] To its south are the first residential areas that got built out as the city expanded—the Mansion and Pastures districts, with the South End just past them.[6] North of downtown most development clusters along Broadway and North Pearl Street (New York State Route 32), since there is more parkland and open space closer to the river.[2]

At the crest of the bluff, just west of downtown, is the Lafayette Park Historic District, distinguished by two monumental government buildings, the state capitol.[7] and State Education Department building. They are complemented by smaller buildings such as city hall, the New York Court of Appeals building, the Old Albany Academy Building (now the main offices of the city's schools[8]) and Cathedral of All Saints, the seat of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany. Four separate small parks besides the district's titular one, with statuary, buffer the capitol and other buildings.[9]

Just to the south of the capitol is Empire State Plaza, a collection of state agency office buildings. Its five sleek modernist towers dominate the core and indeed almost any view of Albany. At the center is the 589-foot (180 m) Erastus Corning Tower, the tallest building in not only Albany[10] but all of upstate New York.[1]

On the south side Empire Plaza is bounded by Madison Avenue (U.S. Route 20), one of Albany's major east–west arteries. Across it is the similarly modern New York State Library, fronted on the east by the two Gothic Revival spires of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, just to the north of the Victorian governor's mansion,[11] which gives the adjacent Mansion District its name.[12]

Lincoln Park, one of Albany's two major parks, which drops gently down to the South End, reflecting another creek that once ran through a ravine here. On its 68 acres (28 ha) are tennis and basketball courts and pools, the largest of which, at 2 acres (8,000 m2) is believed to be the largest cement pool in the Northeast.[13] In the southeast corner is the small brick Italian villa-style James Hall Office, a National Historic Landmark now annexed to a former elementary school building.[14] Between it and the city's southern limit at I-787 are residential neighborhoods around Second Avenue, with the open space of school athletic fields and two smaller city parks on either side.[15]

To the west of the bluff the land generally levels out again.[16] Across the one-block West Capitol Park from the capitol, on the corner of Washington Avenue (at that point also New York State Route 5 (NY 5)) is another tall state office tower, the Art Deco Alfred E. Smith Building. It is a contributing property to the Center Square/Hudson–Park Historic District,[17] the large residential area, its streets lined with rowhouses, that stretches past Lark Street (U.S. Route 9W), the city's main nightlife destination, to Washington Park, the city's largest, with 5.2 acres (2.1 ha) of its 81 acres (33 ha) given over to Washington Park Lake.[18] Madison Avenue on the south and State Street on the south are lined with older rowhouses built to take advantage of the park,[19] and the SUNY at Albany downtown campus, the original location of the University of Albany, is located just to the northwest corner.[20]

The Park South neighborhood, another residential enclave of rowhouses that includes the small Knox Street Historic District, buffers Washington Park from the large campuses of Albany Academy, Albany College of Pharmacy, Albany Law School, Sage College of Albany, and Albany Medical College. This is the center of the University Heights neighborhood. New Scotland Avenue, the neighborhood's northern boundary, leads out into residential areas where the rowhouses give way to frame detached houses. St. Peter's Hospital campus the only significant break.[21]

West of Washington Park is Pine Hills, one of the first neighborhoods in the city to develop along more suburban lines. It is a primarily residential area with the exception of the 48-acre (19 ha) campus of The College of St. Rose[22] and some commercial development along nearby sections of Madison and Western avenues.[23] In the northwest corner of the city, a large industrial park sits next to the Tivoli Preserve, and Central Avenue, which NY 5 follows out of the city, passes through a neighborhood where some larger multiple-unit dwellings begin to intrude amidst the older houses before giving way to a large commercial area near I-90 and the city line.[24]

Immediately west of NY 85 the 330-acre (130 ha) W. Averell Harriman State Office Building Campus, its buildings nested between two ring roads. Just beyond it to the west, only partially located within Albany city limits, is the main campus of SUNY Albany, echoing Empire Plaza with four tall modern dormitory towers arranged in a square pattern around a large central academic pavilion with courtyards and fountains. The campus, too, is surrounded by a ring road. South of Western are more newer residential neighborhoods; between Washington and I-90 are hotels, restaurants and gas stations serving traffic from the nearby interstate exits.[25]

In the western extension of the city, following I-90, is the small residential Rapp Road neighborhood. Artificial Rensselaer Lake, the city's largest body of water at 35.3 acres (14.3 ha),[26] is located just east of the junction of I-90 and the Adirondack Northway. Excelsior College, the Pine Bush Preserve Discovery Center on New York State Route 155, some small residential neighborhoods and the Corporate Circle industrial park are the only breaks in the open space of the Pine Bush which dominates the city's western extremity.[27]

The city's viewshed takes in the river on the east, with some of the Taconic foothills visible further in that direction from taller buildings. To the southwest is the long ridge of the Helderberg Escarpment. The distinctive rooster-comb ridgeline of the Blackhead Range in the northern Catskills, at nearly 4,000 feet (1,200 m) the highest mountains visible from the city, are to the south. On clear enough days the lower Adirondack foothills can be seen in the northern distance, along with the Green Mountains of Vermont to the northeast.

History

[edit]

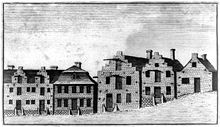

The first building known to have been constructed on the city's present location was a 1540 French fort. This was destroyed by the annual Hudson River freshet and was rebuilt as Fort Nassau by the Dutch in 1614. It too was destroyed and eventually Fort Orange was built in 1624.

Albany's initial architecture incorporated many Dutch influences, followed soon after by those of the English. The Quackenbush House, a Dutch Colonial brick mansion, was built c. 1736.[28] Schuyler Mansion, a 1765 Georgian mansion, was built for Philip Schuyler, an American general during the Revolutionary War and later a United States Senator from New York; it became a National Historic Landmark in 1979.[29] The oldest building currently standing in Albany is the Van Ostrande-Radliff House at 48 Hudson Avenue;[30] scientific testing estimates it was built in 1728.[31]

Albany City Hall, a Richardsonian Romanesque structure designed by Henry Hobson Richardson and opened in 1883, houses Albany's city government. The New York State Capitol was opened in 1899 (after 32 years of construction[7]) at a cost of $25 million, making it the most expensive government building at the time.[33] So notable were these two buildings in their day that in 1885 American Architect and Building News listed them among the top ten most beautiful buildings in the country.[34] Albany's Union Station, a major Beaux-Arts design,[35] was under construction at the same time; it opened in 1900. It was said that "perhaps no other building has been so important to the growth of Albany during the twentieth century as Union Station."[36]

Albany's housing varies greatly, with mostly row houses in the older sections of town, closer to the river. The change in housing type looks like "ripples of housing styles radiating from downtown," with the row houses in the first ring. The second ring includes a surge in two-family homes in the late 19th century, which were serviced by electric street cars. Automobiles made it possible to move even further from downtown; outside the two-family home ring is a ring of one-family homes that were first built after World War II and are still being built today.[37]

The Washington Avenue Armory opened in 1891; technically a Romanesque Revival design, its architect, Isaac Perry, was strongly influenced by Henry Richardson, who had previously worked with Perry on the State Capitol. Today the Armory is an entertainment venue.[38] In 1912, the Beaux-Arts styled New York State Department of Education Building opened on Washington Avenue near the Capitol. It has a classical exterior, which features a block-long white marble colonnade.[39] Later in the decade, Albert W. Fuller's 1917 First Congregational Church of Albany, in the then-undeveloped Woodlawn neighborhood, was the city's first to use the emerging Colonial Revival style.[40]

The 1920s brought the Art Deco movement, which is illustrated by the Home Savings Bank Building (1927) on North Pearl Street[41] and the Alfred E. Smith Building (1930) on South Swan Street,[42] two of Albany's tallest high-rises.[43] Philip Livingston Junior High School, an iconic building at the city's northern gateway, combined high Colonial Revival on the exterior with Art Deco touches inside on its 1932 opening. In 1941, the Miss Albany Diner opened as "Lil's Diner". A classic "Silk City Diner" Art Deco design,[44] Miss Albany is one of the few pre-World War II diners in the United States in near-original condition.[45]

Architecture from the 1960s and 1970s is well represented in the city. Built between 1965 and 1978 at the hand of Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller and architect Wallace Harrison, the Empire State Plaza complex is a powerful example of late American modern architecture[1] and remains a controversial building project both for displacing city residents and for its architectural style. The most recognizable aspect of the complex is the Erastus Corning Tower, the tallest building in the state outside of New York City.[1]

At the opposite end of the city are two more large modern complexes, the W. Averell Harriman State Office Building Campus (1950s and 1960s) and on the uptown campus of the University at Albany (1962–1971). The state office campus, occupying a piece of land totaling nearly 330 acres (130 ha), is home to over 7,000 employees in approximately 16 buildings comprising about 3 million square feet (280,000 m2) of office space.[47][48] It is a suburban-style, car-oriented campus bordered by an outer ring road that cuts the campus off from the surrounding neighborhoods. The state office campus was planned in the 1950s by governor W. Averell Harriman to offer more parking and easier access for state employees. The first building was built in 1956, but most of the buildings were built in the 1960s under Governor Rockefeller.[49]

The uptown SUNY campus was built in the 1960s under Governor Nelson Rockefeller on the site of the city-owned Albany Country Club. Straying from the open campus layout made popular by both Union College in Schenectady and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, SUNY Albany has a centralized building layout. At its core is a large "podium" containing the academic and administrative buildings. Four dormitory complexes, each centered by a high-rise housing tower surrounded by a low-rise grouping of support buildings, are located at each corner of the podium. The architecture called for much use of concrete and glass, and the style has slender, round-topped columns and pillars reminiscent of those at Lincoln Center in New York City.[50]

Downtown Albany has seen a revival in recent decades, often considered to have begun with Norstar Bank's renovation of the former Union Station as its corporate headquarters in 1986.[Note 1] The Times Union Center (TU Center), originally known as Knickerbocker Arena, was once slated for suburban Colonie,[53] but was instead built downtown and opened in 1990.[54] The TU Center, on South Pearl Street, and the renovated Palace Theatre (2003 renovation),[55] on North Pearl Street, have anchored Pearl Street (around State Street) as an entertainment district with many bars and restaurants. Downtown has benefited from the Alive at 5 summer concert series, which takes place at the Corning Preserve, and the block party that follows each show on North Pearl Street.[56] Other development in downtown includes the construction of the Dormitory Authority headquarters at 515 Broadway (1998);[57] the Department of Environmental Conservation building, with its iconic green dome, at 625 Broadway (2001);[58] the State Comptroller headquarters on State Street (2001);[59] the Hudson River Way (2002), a pedestrian bridge connecting Broadway to the Corning Preserve;[60] 677 Broadway (2005), "the first privately owned downtown office building in a generation";[56][61] and a Hampton Inn & Suites (2005) on Chapel Street.[56] The late 2000s saw a real possibility for a long-discussed and controversial Albany Convention Center; as of August 2010, the Albany Convention Center Authority has already purchased 75% of the land needed to build the downtown project.[62]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In 2009, Bank of America (which now owns FleetBank, the bank that eventually bought Norstar) consolidated its operations in an office building on State Street, leaving the former train station vacant.[51] Mayor Corning made great efforts to save the building, which had been owned by his great-grandfather's railroad a hundred years before. He was able to do it when governor Rockefeller brought state money in to purchase the building.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Waite (1993), pp. 81–82

- ^ a b ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by U.S Geological Survey. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Waite, 104.

- ^ John F. Harwood and Austin O'Brien (September 7, 1979). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Downtown Albany Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 28. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Waite (1993), pp. 68–70

- ^ Waite, 72

- ^ C. E. Brook and E. Spencer-Ralph (April 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lafayette Park Historic District". pp. 4–5. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ "Erastus Corning II Tower". CTBUH. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Larson, Neil (July 13, 1982). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Mansion Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 50. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Clabby, Catherine (July 4, 1988). "An Albany 'Treasure' Back in the Swing of Things". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Communications. p. B1. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ James Sheire (July 9, 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: James Hall's Office" (pdf). National Park Service. p. 5. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by U.S Geological Survey. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ T. Robins Brown and E. Spencer-Ralph (1976). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Center Square/Hudson-Park Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. p. 8. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ "Washington Park Lake" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Brooke, Cornelia (May 1972). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Washington Park Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Downtown Campus (PDF) (Map). University at Albany. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "Fast Facts". The College of St. Rose. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ "Rensselaer Lake (Sixmile Waterworks)" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ ACME Mapper (Map). Cartography by Google Maps. ACME Laboratories. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Brooke, Cornelia E. (1972-02-04). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Quackenbush House". Archived from the original on 2011-04-29. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Waite (1993), pp. 48–49

- ^ "Albany Preservation Report" (PDF). Historic Albany Foundation. Spring 2007. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "From De Halve Maen to KLM". American Association for Netherlandic Studies and the New Netherland Institute. 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ^ Waite (1993), pp. 70 – 71

- ^ "Building Big: New York State Capitol". Public Broadcasting Service. 2001. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ Grondahl, Paul (2010-02-06). "Albany buildings reflect dreams, hopes for future". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. A1. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ^ Waite (1993), p. 106

- ^ Liebs, Chester H. (July 1970). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Albany Union Station". Archived from the original on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Scruton, Bruce A. (1986-07-06). "City's Architectural Heritage Diverse, Extensive". Knickerbocker News. Hearst Newspapers (online publisher). p. T52. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ Waite (1993), p. 88

- ^ Waite (1993), pp. 79–80

- ^ "Relocation to 405 Quail Street (1917)". First Congregational Church of Albany. Archived from the original on 2016-01-31. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ Waite (1993), p. 98

- ^ Waite (1993), p. 82

- ^ "Albany: Buildings of the City". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ Gutman, Richard (2000). American Diner Then and Now. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 259. ISBN 0-8018-6536-0.

- ^ Liquori, Donna (1991-10-06). "Miss Albany Diner Turns a Ripe 50". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- ^ McEneny (2006), pp. 122 - 124

- ^ Aaron, Kenneth (2003-02-23). "Big Doings for State Campus". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. C25. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Benjamin, Elizabeth (2005-11-05). "Questioning Grand Plan's Legacy". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. A1. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ McGuire, Mark (1997-09-28). "Dirt, Not Ivy, Covers This Campus". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. A1. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Waite (1993), pp. 241–242

- ^ Churchill, Chris (2009-10-21). "A Landmark Soon to Fall Empty". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 502

- ^ McEneny (2006), p. 194

- ^ McKeon, Michael (1990-02-01). "The Knick: Post-Debut Review Despite Glitches, Arena Withstands First Night". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. B1. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Dalton, Joseph (2003-01-17). "Yo-Yo Ma Grand at New Palace". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. B8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b c Barnes, Steve (2006-10-08). "Eat, drink, be merry. Now what?". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. A1. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ Benjamin, Elizabeth (1999-02-04). "DEC Firms Up Plans for Tower". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. B7. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Cappiello, Dina (2001-09-02). "Workers, DEC Tussle Over Office". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. D3. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ Woodruff, Cathy (2002-01-01). "New Kid on the Block Stands Tall Amid Neighbors". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. p. B1. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ^ "Hudson River Way". Albany County Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ^ "Completed Projects". BBL Development Group. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ Carleo-Evangelist, Jordan (2010-08-27). "Convention center pieces fall into place". Times Union (Albany). Hearst Newspapers. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

Bibliography

[edit]- Grondahl, Paul (2007). Mayor Erastus Corning: Albany Icon, Albany Enigma. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7294-1.

- McEneny, John (2006). Albany, Capital City on the Hudson: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, California: American Historical Press. ISBN 1-892724-53-7.

- Waite, Diana S. (1993). Albany Architecture: A Guide to the City. Albany: Mount Ida Press. ISBN 0-9625368-1-4.