Aosta Valley

Aosta Valley

| |

|---|---|

The Fénis Castle (13th century) and the Aosta Valley | |

|

| |

| Anthem: Montagnes Valdôtaines | |

| |

| Coordinates: 45°45′N 7°26′E / 45.750°N 7.433°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Aosta |

| Government | |

| • President | Renzo Testolin (UV) |

| Area | |

• Total | 3,263 km2 (1,260 sq mi) |

| Population (30 October 2012) | |

• Total | 126,933 |

| • Density | 39/km2 (100/sq mi) |

| • Official languages[1] | Italian French |

| Demonyms | Aostan, Valdostan or Valdotainian[citation needed] Italian: Valdostano (man) Italian: Valdostana (woman) French: Valdôtain (man) French: Valdôtaine (woman) |

| Citizenship | |

| • Italian | 95% |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €4.737 billion (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IT-23 |

| HDI (2021) | 0.889[4] very high · 14th of 21 |

| NUTS Region | ITC |

| Website | Regione.vda.it |

The Aosta Valley (French: Vallée d'Aoste [vale dɔst];[a] Italian: Valle d'Aosta [ˈvalle daˈɔsta]; Arpitan: Val d'Aoûta)[b] is a mountainous autonomous region[6] in northwestern Italy. It is bordered by Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France, to the west; by Valais, Switzerland, to the north; and by Piedmont, Italy, to the south and east. The regional capital is Aosta.

Covering an area of 3,263 km2 (1,260 sq mi) and with a population of about 128,000, it is the smallest, least populous, and least densely populated region of Italy. The province of Aosta having been dissolved in 1945, the Aosta Valley region was the first region of Italy to abolish provincial subdivisions,[7] followed by Friuli-Venezia Giulia in 2017 (where they were reestablished later). Provincial administrative functions are provided by the regional government. The region is divided into 74 comuni (French: communes).

The official languages are Italian and French; Valdôtain, a dialect of Franco-Provençal, is also officially recognized. Italian is spoken as a mother tongue by 77.29% of the population, Valdôtain by 17.91%, and French by 1.25%. In 2009, reportedly 50.53% of the population could speak all three languages.[8]

Geography

[edit]

The Aosta Valley is an Alpine valley which, with its tributary valleys, includes the Italian slopes of Mont Blanc, Monte Rosa, Gran Paradiso and the Matterhorn; its highest peak is Mont Blanc (4,810 m or 15,780 ft). This makes it the highest region in Italy, according to the list of Italian regions by highest point.

Climate

[edit]The valleys, usually above 1,600 m (5,200 ft), annually have a cold continental climate (Dfc). In this climate, the snow season is very long, as long as 8 or 9 months at the highest points. During the summer, mist occurs almost every day. These areas are the wettest in the western Alps. Temperatures in January are low, between −7 and −3 °C (19 and 27 °F), and in July are between 20 and 35 °C (68 and 95 °F).

Areas between 2,000 and 3,500 m (6,600 and 11,500 ft) usually have a tundra climate (ET), where every month has an average temperature below 10 °C (50 °F). This climate may be either a kind of more severe cold oceanic climate, with a low summer average but mild winters, sometimes above −3 °C (27 °F), especially near lakes, or a more severe cold continental climate, with a very low winter average. Temperature averages in Plateau Rosa, at 3,400 m (11,200 ft) high, are −11.6 °C (11.1 °F) in January and 1.4 °C (34.5 °F) in July. It is the coldest place in Italy where the climate is verifiable.[9]

In the past, above 3,500 m (11,500 ft), all months had an average temperature below freezing, with a perpetual frost climate (EF). In recent years, however, there has been a rise in temperatures. See, as an example, the data for Plateau Rosa.[9]

-

Blue Lake[10] and the Matterhorn

History

[edit]

Early inhabitants of the Aosta Valley were Celts and Ligures, whose language heritage remains in some local placenames. Rome conquered the region from the local Salassi around 25 BC and founded Augusta Prætoria Salassorum (modern-day Aosta) to secure the strategic mountain passes, and they went on to build bridges and roads through the mountains. Thus, the name Valle d'Aosta literally means "Valley of Augustus".[11]

In 1031–1032, Humbert I of Savoy, the founder of the House of Savoy, received the title Count of Aosta from Emperor Conrad II of the Franconian line and built himself a commanding fortification at Bard. Saint Anselm of Canterbury was born in Aosta in 1033 or 1034. The region was divided among strongly fortified castles, and in 1191, Thomas I of Savoy found it necessary to grant to the communes a Charte des franchises ("Charter of Liberties") which preserved autonomy—rights that were fiercely defended until 1770, when they were revoked to tie Aosta more closely to Piedmont, but which were again demanded during post-Napoleonic times. In the mid-13th century, Emperor Frederick II made the County of Aosta a duchy (see Duke of Aosta), and its arms charged with a lion rampant were carried in the Savoy arms until the reunification of Italy in 1870.[13]

The region remained part of Savoy lands, with the exceptions of French occupations from 1539 to 1563, later in 1691, and then between 1704 and 1706. It was also ruled by the First French Empire between 1800 and 1814. During French rule, it was part of Aoste arrondissement in Doire department.[14] As part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, it joined the new Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

French forces briefly controlled the area at the end of World War II, but withdrew under British and American pressure.[15] The region gained special autonomous status after the end of World War II; the province of Aosta ceased to exist in 1945.[7]

Government and politics

[edit]For decades, the valley has been dominated by autonomist regional parties such as the Valdostan Union, which represents the interests of the French-speaking population.[16] The latest regional election was held in September 2020. On 2 March 2023, Renzo Testolin was elected regional president, supported by a coalition of autonomist and progressive lists.[17]

The Aosta Valley, being the smallest region of Italy by area, is not divided into provinces. Nevertheless, it is still divided into 74 comunes namely:

| ISTAT code | Municipality | Population (2005) |

|---|---|---|

| 007001 | Allein | 243 |

| 007002 | Antey-Saint-André | 602 |

| 007003 | Aosta / Aoste | 34,270 |

| 007004 | Arnad | 1,294 |

| 007005 | Arvier | 848 |

| 007006 | Avise | 312 |

| 007007 | Ayas | 1,296 |

| 007008 | Aymavilles | 1,966 |

| 007009 | Bard | 135 |

| 007010 | Bionaz | 244 |

| 007011 | Brissogne | 962 |

| 007012 | Brusson | 860 |

| 007013 | Challand-Saint-Anselme | 695 |

| 007014 | Challand-Saint-Victor | 589 |

| 007015 | Chambave | 937 |

| 007016 | Chamois | 99 |

| 007017 | Champdepraz | 674 |

| 007018 | Champorcher | 417 |

| 007019 | Charvensod | 2,333 |

| 007020 | Châtillon | 4,846 |

| 007021 | Cogne | 1,470 |

| 007022 | Courmayeur | 2,979 |

| 007023 | Donnas | 2,661 |

| 007024 | Doues | 409 |

| 007025 | Émarèse | 217 |

| 007026 | Étroubles | 472 |

| 007027 | Fénis | 1,653 |

| 007028 | Fontainemore | 412 |

| 007029 | Gaby | 490 |

| 007030 | Gignod | 1,352 |

| 007031 | Gressan | 2,981 |

| 007032 | Gressoney-La-Trinité | 306 |

| 007033 | Gressoney-Saint-Jean | 799 |

| 007034 | Hône | 1,162 |

| 007035 | Introd | 573 |

| 007036 | Issime | 400 |

| 007037 | Issogne | 1,374 |

| 007038 | Jovençan | 709 |

| 007039 | La Magdeleine | 95 |

| 007040 | La Salle | 1,985 |

| 007041 | La Thuile | 766 |

| 007042 | Lillianes | 494 |

| 007043 | Montjovet | 1,795 |

| 007044 | Morgex | 1,938 |

| 007045 | Nus | 2,713 |

| 007046 | Ollomont | 161 |

| 007047 | Oyace | 211 |

| 007048 | Perloz | 467 |

| 007049 | Pollein | 1,441 |

| 007050 | Pontboset | 190 |

| 007051 | Pontey | 742 |

| 007052 | Pont-Saint-Martin | 3,957 |

| 007053 | Pré-Saint-Didier | 968 |

| 007054 | Quart | 3,263 |

| 007055 | Rhêmes-Notre-Dame | 124 |

| 007056 | Rhêmes-Saint-Georges | 200 |

| 007057 | Roisan | 900 |

| 007058 | Saint-Christophe | 3,124 |

| 007059 | Saint-Denis | 361 |

| 007060 | Saint-Marcel | 1,206 |

| 007061 | Saint-Nicolas | 325 |

| 007062 | Saint-Oyen | 218 |

| 007063 | Saint-Pierre | 2,785 |

| 007064 | Saint-Rhémy-en-Bosses | 387 |

| 007065 | Saint-Vincent | 4,833 |

| 007066 | Sarre | 4,434 |

| 007067 | Torgnon | 522 |

| 007068 | Valgrisenche | 184 |

| 007069 | Valpelline | 627 |

| 007070 | Valsavarenche | 178 |

| 007071 | Valtournenche | 2,169 |

| 007072 | Verrayes | 1,305 |

| 007073 | Verrès | 2,623 |

| 007074 | Villeneuve | 1,136 |

| Total | 122,868 |

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 81,884 | — |

| 1871 | 81,260 | −0.8% |

| 1881 | 85,007 | +4.6% |

| 1901 | 83,529 | −1.7% |

| 1911 | 80,680 | −3.4% |

| 1921 | 82,769 | +2.6% |

| 1931 | 83,479 | +0.9% |

| 1936 | 83,455 | −0.0% |

| 1951 | 94,140 | +12.8% |

| 1961 | 100,959 | +7.2% |

| 1971 | 109,150 | +8.1% |

| 1981 | 112,353 | +2.9% |

| 1991 | 115,938 | +3.2% |

| 2001 | 119,548 | +3.1% |

| 2011 | 126,806 | +6.1% |

| 2021 | 123,360 | −2.7% |

| Source: ISTAT | ||

| Nationality | Population |

|---|---|

| 2,361 | |

| 1,553 | |

| 695 | |

| 298 | |

| 272 | |

| 261 | |

| 235 | |

| 220 | |

| 179 | |

| 160 | |

| 144 | |

| 105 | |

| 102 |

The population density of Aosta Valley is by far the lowest of the Italian regions. In 2008, 38.9 inhabitants per km2 were registered in the region, whereas the average national figure was 198.8, though the region has extensive uninhabitable areas of mountain and glacier, with a substantial part of the population living in the central valley.

Negative natural population growth since 1976 has been more than offset by immigration. The region has one of Italy's lowest birth rates, with a rising average age. This, too, is partly compensated by immigration, since most immigrants arriving in the region are younger people working in the tourist industry. Between 1991 and 2001, the population of Aosta Valley grew by 3.1%, which is the highest growth among the Italian regions. With a negative natural population growth, this is due exclusively to positive net migration.[2] Between 2001 and 2011, the population of Aosta Valley grew by a further 7.07%. As of 2006[update], the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) estimated that 4,976 foreign-born immigrants live in Aosta Valley, equal to 4.0% of the total regional population.

The Valdôtain population and their language dialects have been the subject of some sociological research.[19]

Culture

[edit]Languages

[edit]The Aosta Valley was the first government authority to adopt Modern French as the official language in 1536, three years before France itself.[20]

Since 1946, Italian and French are the region's official languages[1] and are used for the regional government's acts and laws, though Italian is much more widely spoken in everyday life, and French is mostly spoken in cultural life. Education is conducted evenly in French and Italian,[1] so that anyone who has gone to school in the Aosta Valley can speak both languages to at least a medium-high level.[21]

Legal decree No.365 of 11 November 1946 (art.2) states that it is mandatory to know both Italian and French to teach in Aosta Valley's schools.[22] According to Aosta Valley's autonomous status (art.39), the same quantity of hours of French and Italian teaching must be held.[23] The decree No.861 of the President of the Republic of 31 October 1975 (art.5) states that it is mandatory to pass a French exam to teach in Aosta Valley for Italian native speakers, as well an Italian exam for French native speakers.[24] Italian law No.196 of 16 May 1978 states the adaptation rules of national educational programmes into French for Aosta Valley, and states as well that all members of the examination boards must be fluent both in Italian and French.[25] Aosta Valley students must pass an extra test in French at the Secondary education final exam, similar to the first test (in Italian).

The regional language, known as patoué valdotèn or simply patoué (patois valdôtain in French), is a dialectal variety of Franco-Provençal. It is spoken as a native and second language by 68,000 residents, or about 58% of the population according to a sociolinguistic survey carried out by the Fondation Émile Chanoux in 2001.[26]

The survey found that the Italian language was native to 77.29% of respondents, Franco-Provençal to 17.91%, and French to 1.25%, though the active use of these languages by the population shows French at 75.41% and Franco-Provençal at 55.77%. The population of Gressoney-Saint-Jean, Gressoney-La-Trinité and Issime, in the Lys Valley, speak two dialects of Walser German, Titsch and Töitschu respectively.[21] According to the survey, Walser German was spoken as a mother tongue by 207 people, or 17.78%, in these three villages. Nevertheless, it was known to 56.38% of the population.[27]

Castles and fortresses

[edit]There are numerous medieval castles and fortified houses in the Aosta Valley, including Châtel-Argent, Saint-Pierre Castle, Fénis Castle, Issogne Castle, Bard Fort, Ussel Castle, Sarre Castle, Cly Castle, Verrès Castle, and Châtelard Castle.[28] Savoy Castle in Gressoney-Saint-Jean was conceived in the 19th century and completed in 1904.[28] Since 1990, it has also been home to the Savoy Castle Alpine Botanical Garden.

-

The Sarre Castle

-

The Verrès Castle

-

The Issogne Castle

-

The Bard Fort

-

The Savoy Castle

-

The Châtel-Argent

Cuisine

[edit]

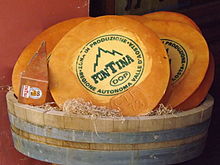

The cuisine of Aosta Valley is characterized by simplicity and revolves around "robust" ingredients such as potatoes, polenta; cheese and meat; and rye bread. Many of the dishes involve Fontina,[30] a cheese with PDO status, made from cow's milk that originates from the valley. It is found in dishes such as the soup à la vâpeuleunèntse[31] (Valpelline Soup). Other cheeses made in the region are Tomme de Gressoney[32] and Seras. Fromadzo (Valdôtain for cheese) has been produced locally since the 15th century and also has PDO status.[33]

Regional specialities, besides Fontina, are Motzetta (dried chamois meat), Vallée d'Aoste Lard d'Arnad[34] (a cured and brined fatback product with PDO designation), Vallée d'Aoste Jambon de Bosses[35] (a kind of ham, likewise with PDO designation), a dark bread made with rye, and honey.

Notable dishes include Carbonnade, similar to the Belgian dish of the same name consisting of salt-cured beef cooked with onions and red wine served with polenta; breaded veal cutlets called costolette; teuteuns,[36] salt-cured cow's udder that is cooked and sliced; and steak à la valdôtaine,[37] a steak with croûtons, ham and melted cheese.

Historic villages

[edit]

Aosta Valley has many small and picturesque villages, three of them have been selected by I Borghi più belli d'Italia (English: The most beautiful Villages of Italy),[38] a non-profit private association of small Italian towns of strong historical and artistic interest,[39] that was founded on the initiative of the Tourism Council of the National Association of Italian Municipalities.[40]

Wine growing

[edit]Notable wines include two white wines from Morgex (Blanc de Morgex et de La Salle and Chaudelune), a red wine blend from Arvier (Enfer d'Arvier) and one from Gamay.[41]

Frazione

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

The prehistoric site near Chenal castle, Montjovet, rich in petroglyphs

-

A view from refuge Albert Deffeyes, La Thuile

See also

[edit]- Alps-Mediterranean Euroregion

- Arch of Augustus in Aosta

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Aosta

- Elections in Aosta Valley

- Bard Fort – Museum of the Alps

- Gran Paradiso National Park

- List of presidents of Aosta Valley

- Mont Blanc

- Mont Blanc Tunnel

- Roman bridge Pont d'Aël

- Refuge Grand Tournalin

- Roman Theatre, Aosta

- 13th-century bridge of Grand Arvou

Notes

[edit]- ^ If pronounced in Aostan French; [vale daɔst] if pronounced in Standard French.[5] Also informally known as Val d'Aoste or Val d'Aosta in French and Italian respectively.

- ^ Walser: Augschtalann or Ougstalland; Piedmontese: Val d'Osta.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Statut spécial de la Vallee d'Aoste" (in French). Conseil régional de la Vallée d'Aoste. 2001. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT" (in Italian). Demo.istat.it. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ Regions and Cities > Regional Statistics > Regional Economy > Regional Gross Domestic Product (Small regions TL3), OECD.Stats. Accessed on 16 November 2018.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Jean-Marie Pierret (1994). Phonétique historique du français et notions de phonétique générale (in French). Louvain-la-Neuve: Peeters. p. 104.

- ^ "Le Statut spécial de la Vallée d'Aoste". 1948. Retrieved 10 July 2017. Articles 1 and 48b of the constitutional law officially assert the region's autonomy.

- ^ a b "Italian Parliament – VI Commission document 2000-07-18 (in Italian)" (PDF).

- ^ Decime, R.; Vernetto, G., eds. (2009). Profil de la politique linguistique de la Vallée d'Aoste (in French). Le Château. p. 20.

- ^ a b "Tempo in atto su Plateau Rosa". meteoam.it. 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Lovevda.it

- ^ Poling, Dean (12 October 2009). "What does Valdosta mean?". Valdosta Daily Times. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "ESO Astronomy Camp for Secondary School Students". eso.org. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ François Velde (2000). "Heraldry in the House of Savoia". Heraldica. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ Almanach Impérial an bissextil MDCCCXII, pp. 392–393, accessed in Gallica 18 February 2015 (in French)

- ^ Harris, Charles Reginald Schiller (1957). Allied military administration of Italy, 1943–1945. H. M. Stationery Office. pp. 318–20.

- ^ Vampa, Davide (15 September 2016). The Regional Politics of Welfare in Italy, Spain and Great Britain. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-39007-9.

- ^ "Regione Valle d'Aosta, Renzo Testolin è il nuovo presidente - Valle d'Aosta". 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Citizens. Resident Population by sex and citizenship on 31st December 2019". National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Saint-Blancat, Chantal (1984). "The Effect of Minority Group Vitality upon Its Sociopsychological Behaviour and Strategies". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 5 (6): 511–516. doi:10.1080/01434632.1984.9994177.

Cooper, Danielle Chavy (1987). "Voices from the Alps: Literature in Val d'Aoste Today". World Literature Today. 61 (1): 24–27. doi:10.2307/40142443. JSTOR 40142443. - ^ Caniggia, Mauro; Poggianti, Luca (25 October 2012). "La Vallée d'Aoste: enclave francophone au sud-est du Mont Blanc" (in French). Zigzag magazine. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b AA. VV. "Une Vallée d'Aoste bilingue dans une Europe plurilingue". in French and Italian. Aoste: Fondation Émile Chanoux. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ D.Lgs.C.P.S. 11 novembre 1946, n. 365. Ordinamento delle scuole e del personale insegnante della Valle d'Aosta ed istituzione nella Valle stessa di una Sovraintendenza agli studi.

- ^ Loi constitutionnelle n° 4 du 26 février 1948 – Statut spécial pour la Vallée d'Aoste.

- ^ D.P.R. 31 ottobre 1975, n. 861. – Organici delle scuole primarie, secondarie ed artistiche della Valle d'Aosta.

- ^ Legge del 16 maggio 1978, n. 196 – Norme di attuazione dello statuto speciale della Valle d'Aosta. (GU Serie Generale n.141 del 23-05-1978)

- ^ a b c "Sondaggio linguistico: Q 0301 Lingua materna – Qual è la sua lingua materna?". Fondation Émile Chanoux (in Italian and French). Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Sondaggio Linguistico Comunità Walser". Fondation Émile Chanoux (in Italian and French). Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ a b Massetti, E. "Aosta Valley Castles" n.d., accessed 15 March 2014.

- ^ Aosta Valley Regional Museum of Natural Science museoscienze.it

- ^ "Fontina". Valle D'Aosta Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Seupa à la Vapelenentse (Valpelline Soup)". Valle D'Aosta Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Gressoney toma cheese". Aosta Valley Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Fromadzo cheese". Valle D'Aosta Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Valleé d'Aoste Lard d'Arnad". Aosta Valley Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Vallée d'Aoste Jambon de Bosses". Aosta Valley Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "The Teuteun". Valle D'Aosta Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Steak Valdaostan style" (in Italian). Consorzio Produttori e Tutela Della Fontina DOP. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Valle d'Aosta" (in Italian). 9 January 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Borghi più belli d'Italia. Le 14 novità 2023, dal Trentino alla Calabria" (in Italian). 16 January 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "I Borghi più belli d'Italia, la guida online ai piccoli centri dell'Italia nascosta" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "D.O.C. Wine". Valle D'Aosta Official Tourism Website. 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Cerutti, Augusta Vittoria, Le Pays de la Doire et son peuple, Quart: éditeur Musumeci

- Colliard, Lin (1976), La culture valdôtaine au cours des siècles, Aoste

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Henry, Joseph-Marie (1967), Histoire de la Vallée d'Aoste, Aoste: Imprimerie Marguerettaz

- Janin, Bernard (1976), Le Val d'Aoste. Tradition et renouveau, Quart: éditeur Musumeci

- Riccarand, Elio, Storia della Valle d'Aosta contemporanea (1919–1945), Aoste: Stylos Aoste

External links

[edit]- Website of the Aosta Valley Regional Authority (in Italian and French)

- Official Tourism website

- Aosta Valley

- Autonomous regions of Italy

- Arpitania

- Provinces of Italy

- Regions of Italy

- Valleys of Italy

- Valleys of the Alps

- Castles in Aosta Valley

- French-speaking countries and territories

- NUTS 2 statistical regions of the European Union

- Regions of Europe with multiple official languages

- Wine regions of Italy

![Blue Lake[10] and the Matterhorn](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Cervino_dal_Lac_Bleu.jpg/280px-Cervino_dal_Lac_Bleu.jpg)

![The Saint-Pierre Castle[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/CastelloDiSaintPierreJuly312023_03.jpg/200px-CastelloDiSaintPierreJuly312023_03.jpg)

![The Sarre Castle [it]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/54/CastelloDiSarreJuly312023_03.jpg/200px-CastelloDiSarreJuly312023_03.jpg)

![The Aymavilles Castle [it]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/CastelloDiAymavillesJuly312023_02.jpg/200px-CastelloDiAymavillesJuly312023_02.jpg)