Aydin Aghdashloo

Aydin Aghdashloo | |

|---|---|

| آیدین آغداشلو | |

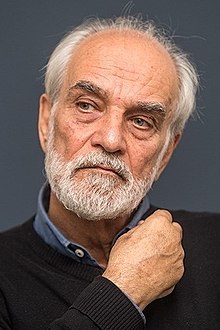

Aghdashloo in 2014 | |

| Born | October 30, 1940 Rasht, Iran |

| Other names | Faramarz Kheybari |

| Education | Tehran University |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | Termination Memories Falling Angels Identity: In Praise of Sandro Botticelli |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2, including Tara |

| Honours | Legion of Honour |

| Website | aghdashloo |

Aydin Aghdashloo (Persian: آیدین آغداشلو; born October 30, 1940) is an Iranian painter, graphic artist, art curator, writer, and film critic.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Aydin Aghdashloo, the son of Mohammad-Beik Aghdashloo (Haji Ouf) and Nahid Nakhjevan,[2] was born on October 30, 1940, in the Afakhray neighborhood of Rasht.[3] His father was an Azerbaijani Turk and a member of Azerbaijan Equality Party and his family assumes their surname from the small town of Agdash.[4] After seeing Aydin's talent in painting at school and his hand-made models, Mohammad-Beik took him to Habib Mohammadi, a painter and a teacher from Rasht.

In 1959, at 19, after successfully passing the university entrance examination, he enrolled in Tehran University's School of Fine Arts. In 1967, he decided to leave the program during its final year.[5]

Works

[edit]In 1975, Aghdashloo held his first individual exhibition at Iran-America Society in Tehran. The exhibited paintings were mostly about floating things, dolls and some works about the Renaissance. Between 1976 and 1979, Aghdashloo helped open and launch Museums Abghineh va Sofalineh, Reza Abbasi Museum and Contemporary Arts in Tehran and also Kerman and Khorram-Abad Museums.[3]

Aghdashloo was the holder and coordinator of several exhibitions after the Iranian Revolution. While none of them were special exhibitions of his works, they played an important role in introducing contemporary Iranian art to the people inside and outside Iran. He took multiple exhibitions from Iran to other countries, including "Iranian Art, since the Past until Today" in China, "Past Iranian Art" in Japan, and the contemporary Iranian paintings with a traditional background sent to Bologna, Italy.[4] Aghdashloo is also a recipient of the Legion of Honour.[6]

Aghdashloo's interest in including surreal spaces in his works and painting floating objects began at his 30 years of age. During the period, his works were of floating objects having a shadow on the ground. In a surrealistic environment, he painted dolls having no faces influenced by Gergeo Deki Riko, and they later became a large part of his series "Years of Fire and Snow". According to him, painting of such faceless dolls helped him say the subconscious suspicious and illusive words in the form of a painting.[7]

After the 1979 revolution and the eight-year war, most of Aghdashloo's works were about memorials and objects proceeding to doom and damage; abandoned huts and views, green wooden rotten windows with broken glasses, old doors with rusted locks, and deadly blades as symbols of missiles hitting the cities; all of them showed the painter's thinking of gradual doom and damage as the passing of hard times. Using Iranian miniature continued in his works and he used every Iranian classic style and space for transferring his subjective concepts about the contemporary world.

Aghdashloo paints most of his works by gouache on canvas.

Bahram Beyzai writes in a part of his article: "Why shouldn't I be rude and say that if there's a value in copy-painting, the patterns of the previous celebrities of painting and visualizing aren't in our reach; so that as evaluation criteria, they can testify for the level of accomplishment of those masters in copy-painting; but their works, which Aydin has remade, are proof of Aydin's skill in copy-painting. Copy-painting wasn't all of their art, as it's not all of Aydin's. It's Aydin's imagination and time-sighting and death-aware thought that's the final maker of his work. The notches that time has made in the paintings and the oppressions that the cosmos – or man's hand – has inflicted upon them. In Aydin's repaintings, these masters' praise is accompanied by sorrow for their own and their works' mortality."[8]

In a ceremony that was held in the French embassy in Iran on Tuesday, January 12, 2016, Aghdashloo received the Legion of Honour.[6]

Aghdashloo participated in the exhibition "Memling Now" in October 2021, which aimed to showcase the enduring impact of Hans Memling on the realm of contemporary art. The exhibition prominently featured the works of Aghdashloo alongside other notable artists.[9][10][11]

In Summer 2022 Aydin Aghdashloo was a speaker in commemoration of his longtime friend and collaborator Abbas Kiarostami.[12]

His work was also part of August 26 – September 22, 2022 "A Nostalgic Glimpse Into the Recent Art of Iran" at Homa Art Gallery in Tehran.[13]

Controversy

[edit]Allegations of sexual misconduct

[edit]On August 22, 2020, Sara Omatali, a former reporter, publicly stated that during an encounter in late 2006, Aydin Aghdashloo forcibly grabbed her and kissed her in his office, where they had met for an interview.[14][15] On August 27, 2020, Aghdashloo issued English and Persian public statements denying the allegations and expressing his support for women's movements, stating that false accusations made it difficult for real victims to seek justice.[16]

Barbad Golshiri, son of Iranian author Houshang Golshiri, announced that the new edition of his father's novel, Prince Ehtejab, would not include Aghdashloo's painting.[17]

Investigation in The New York Times

[edit]On October 22, 2020, Farnaz Fassihi published two months' worth of investigations, interviewing alleged victims of Aghdashloo in The New York Times.[15] The investigation included 13 women who accused Aghdashloo of sexual abuse, including one who was underage.

After the release of the New York Times article, one of the cited sources, Solmaz Naraghi, publicly stated that the report misrepresented her statement. Subsequently, the New York Times made an amendment, incorporating the term 'verbal' into the abuse allegations in the Persian-language article (not reflected in the English-language version).[18]

In an interview with Houman Mortazavi for Tajrobeh Magazine, Aghdashloo shared insights into his perception of power and responsibility within society.

"One of the reasons I started lecturing and teaching was to share of my knowledge with others. I have never abused this position. At least consciously, I never used it. Maybe I got the love of the community because of it, but it was nothing more."

Furthermore, he acknowledged making mistakes in life but refuted the claims made in a New York Times article and by a source blogger, labeling them as documents and forgeries aimed at ulterior motives such as tarnishing his reputation.[19]

205 individuals, including artists, gallery owners, and art critics, have raised concerns about similarities between the New York Times article and narratives about Mr. Afshin Parvaresh, a social media investigative reporter, over the past four to five years. They question if the article relies on Mr. Parvaresh's information and why it hasn't been presented in court if accurate. This inquiry adds complexity to discussions about Aghdashloo's situation, prompting questions about information credibility and legal processes.[20]

Solidarity Collective Responding to Accusations

[edit]On September 8, 2020, a group of students of Iranian artist Aydin Aghdashloo released a collective statement, emphasizing the demand for the rights of all, especially women. More than 150 of Aydin’s students signed a statement in support of him and describe the safe and supportive environment in which they were his students.[21][22] The students, spanning various decades of Aghdashloo's courses, described him as an inspiring teacher and caring figure. Addressing accusations against Aghdashloo, the statement explained their deliberate choice of silence to avoid contributing to a smear campaign and expressed a hope for the genuine demands of the community to find truth. The statement, concluding with a list of endorsing students, offers insight into Aghdashloo's impact as perceived by those who have directly experienced his teachings and mentorship.[23]

Personal life

[edit]From 1972 until 1980, he was married to actress Shohreh Aghdashloo (née Vaziri-Tabar).[24] In 1981 he married the architect Firouzeh "Fay" Athari. Together they had two children, Takin and Tara Aghdashloo. They are divorced.[25][26][27]

On September 25, 2022, Aydin Aghdashloo was the first prominent Iranian painter to release a personal statement in support of the protests that were sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini by Iran’s Morality Police. He was also one of the signers on a collective statement by Iranian artists, scholars, critics, art historians and curators in support of the student protests in the country published on October 20, 2022.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "BBC فارسی - فرهنگ و هنر - از دور و نزدیک؛ نگاهی به نوشتههای سینمایی آیدین آغداشلو". bbc.com (in Persian). Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Bayzai, Bahram. About Aydin Aghdashloo and His Art.

- ^ a b Maskub, Taraneh. The Calendar of Aydin Aghdashloo's Life.

- ^ a b Karimian, Rambod (1993). "An Interview with Aydin Aghdashloo". Kalak.

- ^ "AYDIN AGHDASHLOO". Assar Art Gallery.

- ^ a b "آیدین آغداشلو، نقاش ایرانی، نشان شوالیه فرانسه را دریافت کرد". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). January 13, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Murizinezhad, Hasan. Contemporary Iranian Artists: Aydin Aghdashloo.

- ^ Beyzai. About Aydin Aghdashloo and His Art.

- ^ "Memling Now: Memling in contemporary art". Arte por Excelencias. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Memling Now: Hans Memling in Contemporary Art". CODART. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Memling Now: Hans Memling in contemporary art". Musea Brugge. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "آیدین آغداشلو: جهان با عباس کیارستمی معنای تازهای پیدا کرد - ایسنا". www.isna.ir. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "group show - A Nostalgic Glimpse | Darz". darz.art. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Alinejad, Masih; Hakakian, Roya (August 26, 2020). "Iranian women are staging an offensive against sexual abuse. It's long overdue". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Fassihi, Farnaz (October 23, 2020). "A #MeToo Awakening Stirs in Iran". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Posts [@aydin_aghdashloo Instagram profile]". August 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Aghdashloo design removed from Prince Ehtejab cover, after being accused of "sexual harassment"". Aznews TV. August 30, 2020.

- ^ "Farnaz Fassihi misrepresented Solmaz Naraghi's words. – Aydin Aghdashloo Facts". Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Cassagnou, M (April 2020). "THE USE OF 3D VIRTUAL REALITY IN ENDO-ULTRASONOGRAPHY FOR RECTAL ADENOCARCINOMA: A NEW CONCEPT, FOR A NEW SOFTWARE APPLICATION (https://WWW.3D-EUS.FR)". ESGE Days. © Georg Thieme Verlag KG. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1704652.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Why do Aghdashloo's fans consider the NYT report unfair?/ Farnaz Fassihi and her ten incredible points". Iran arts. May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "Aydin Aghdashloo's Students never saw the behavior suggested. – Aydin Aghdashloo Facts". Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Statement of a Group of Aydin Aghdashloo Students". Iran arts. March 22, 2024. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Statement of a Group of Aydin Aghdashloo Students". Iran arts. January 31, 2024. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Shohreh Aghdashloo Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz; Porter, Catherine (November 2, 2020). "Famed Iranian Artist Under #MeToo Cloud Faces Art World Repercussions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ "Style Talk, Meet Tara Aghdashloo". Les Belles Heures. June 1, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

my own father Aydin Aghdashloo,

- ^ "An Interview With Abbas Kiarostami and Aydin Aghdashloo". Offscreen, Volume 21 Issue 7. July 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

Takin, my son!

- ^ "Instagram". www.instagram.com. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

Lucie-Smith, Edward (September 1999). Art Today. Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3888-8.

External links

[edit]- Aydin Aghdashloo's Official Website

- Ali Dehbāshi, Aghdashloo, a passer-by by the side of the wall (Aghdashloo, āberi dar kenār-e divār), in Persian, Jadid Online, January 30, 2009, [1].

• Aghdashloo: Living to Paint, in English, Jadid Online, May 14, 2009, [2].

• Audio slideshow by Shokā Sahrā'i, in Persian (with English subtitles), Jadid Online, 2009: [3] (7 min 6 sec).

- Iranian painters

- Contemporary painters

- Iranian graphic designers

- Iranian art critics

- Iranian people of Azerbaijani descent

- People from Rasht

- 1940 births

- Living people

- Iranian poster artists

- Iranian watercolourists

- Iranian contemporary artists

- Iranian art writers

- 20th-century Iranian people

- 21st-century Iranian people