1998 Nobel Prize in Literature

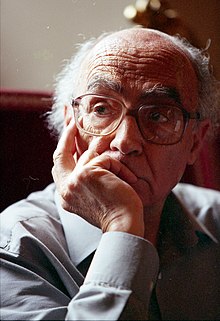

| José Saramago | |

"who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality." | |

| Date |

|

| Location | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Presented by | Swedish Academy |

| First award | 1901 |

| Website | Official website |

The 1998 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Portuguese author José Saramago (1922–2010) "who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality."[1] He is the only recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature from Portugal.[2][3]

Laureate

[edit]José Saramago frequently makes use of allegory in his writing, and fanciful elements are interspersed with a detailed and critical look at society. A characteristic of Saramago's style is the blending of dialog and narration, in parabolic forms, with sparse punctuation and long sentences that can extend for several pages. In one of his most successful novels, Ensaio sobre a Cegueira ("Blindness", 1995), the population is stricken with an epidemic of blindness that quickly leads to societal collapse.[4] Among his other well-known literary masterpieces include Memorial do Convento ("Baltasar and Blimunda", 1982), O Ano da Morte de Ricardo Reis ("The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis", 1984), História do Cerco de Lisboa ("The History of the Siege of Lisbon", 1989), and O Evangelho Segundo Jesus Cristo ("The Gospel According to Jesus Christ", 1991).[2][4] Saramago's last published work was Caim ("Cain", 2009), which narrates Adam and Eve's son as he witnesses and recounts passages from the Bible that add to his increasing hatred of God.[2]

Reactions

[edit]The choice of Saramago as the Nobel Prize laureate was internationally generally well received. One commentator in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter described it as a safe choice: "an authorship that is appreciated by everyone and won't be questioned by anyone". In Saramago's home country reactions were however radically mixed, lauded by the left wing press and heavily criticised by the bourgeois press.[5]

Following the Swedish Academy's decision to present Saramago with the Nobel Prize in Literature, the Vatican City questioned the decision on political grounds, though gave no comment on the aesthetic or literary components of his work. Saramago responded: "The Vatican is easily scandalized, especially by people from outside. They should just focus on their prayers and leave people in peace. I respect those who believe, but I have no respect for the institution."[6] He received the news when he was about to fly to Germany for the Frankfurt Book Fair, and caught both him and his editor by surprise.[7]

Award ceremony speech

[edit]At the award ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December 1998, Kjell Espmark of the Swedish Academy said of Saramago's writing:

This rich work, with its constantly shifting perspectives and constantly renewed images of the world, is held together by a narrator whose voice is with us all the time. Apparently he is a story-teller of the old-fashioned omniscient variety, a master of ceremonies standing on the stage next to his creations, commenting on them, guiding their steps and sometimes winking at us across the footlights. But Saramago uses these traditional techniques with amused distance. The narrator is also adept in the contemporary devices of the absurd and develops a modern scepticism when faced with the omniscient claim to be able to say how things stand.The result is literature characterised at one and the same time by sagacious reflection and by insight into the limitations of sagacity, by the fantastic and by precise realism, by cautious empathy and by critical acuity, by warmth and by irony. This is Saramago’s unique amalgam.[8]

Nobel Prize Museum

[edit]In 2024, Saramago's widow Pilar del Rio and the José Saramago Foundation donated a number of Saramago's belongings to the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm, including a pair of his glasses, a stone found in Lanzarote that was important to him, and a manuscript written in his youth.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 1998 nobelprize.org

- ^ a b c José Saramago britannica.com

- ^ Alan Riding (8 October 1998). "Nobel in Literature Goes to Jose Saramago". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ a b José Saramago – Facts nobelprize.org

- ^ Helmer Lång Hundra nobelpris i littedatur 1901-2001, Symposion 2001, p.376-377

- ^ "Nobel Writer, A Communist, Defends Work". The New York Times. 12 October 1998. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Quoted in: Eberstadt, Fernanda (26 August 2007). "The Unexpected Fantasist". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ "Award ceremony speech". nobelprize.org.

- ^ "Föremål från José Saramago har skänkts till Nobelprismuseet" (in Swedish). Nobel Prize Museum. 1 March 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1998 Press release nobelprize.org

- Award ceremony speech nobelprize.org

- Award ceremony video nobelprize.org

- José Saramago Nobel lecture nobelprize.org

- José Saramago Banquet speech nobelprize.org

- Nobel diploma nobelprize.org

- Photo gallery nobelprize.org

- Excerpt from Baltasar and Blimunda by José Saramago nobelprize.org