Réseau Express Régional

| Réseau Express Régional (RER) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

RER C train at Villeneuve-le-Roi station | |||

| Overview | |||

| Owner | RATP and SNCF | ||

| Locale | Île-de-France, Hauts-de-France and Centre-Val de Loire | ||

| Transit type | Hybrid commuter rail and rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 5 | ||

| Number of stations | 257 | ||

| Annual ridership | 983 million (2019)[1] | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 9 December 1977 | ||

| Operator(s) | RATP (RER A and B) SNCF (all lines) | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 602 km (374 mi) | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | Overhead line, 1,500 V DC (RATP) or 25 kV 50 Hz AC (SNCF) | ||

| Top speed | 140 km/h (90 mph) | ||

| |||

The Réseau Express Régional (French pronunciation: [ʁezo ɛkspʁɛs ʁeʒjɔnal]; English: Regional Express Network), commonly abbreviated RER (pronounced [ɛʁ.ə.ɛʁ]), is a hybrid commuter rail and rapid transit system, similar to the S-Bahns of German-speaking countries and the S Lines of Milan, serving Paris and its suburbs. It acts as a combined city-center underground rail system and suburbs-to-city-center commuter rail. In the city center, it acts as a faster counterpart of the Paris Métro, having fewer stops.

Conceived of as a "métropolitain express" (express metro) during the mid 1930s, the scheme was revived in the 1950s and construction began in the early 1960s. The RER was not fully conceptualised until the completion of the Schéma directeur d'aménagement et d'urbanisme (roughly: "master plan for urban development") in 1965. The RER network, which initially comprised two lines, was formally inaugurated on 8 December 1977 in a ceremony that was attended by President Valery Giscard D'Estaing. A second phase of construction commenced at the end of the 1970s which saw additional lines constructed along with extensions to the original two. The RER is operated partly by RATP, the authority that operates most of the public transport in Paris, and partly by SNCF, France's national rail operator.

As of 2023, the network consists of five lines: A, B, C, D and E. The network has 257 stations and has interchanges with the Métro and commuter rail within the City of Paris and the suburbs. The lines are identified by letters to avoid confusion with the Métro lines, which are identified by numbers. The network is still expanding: RER E, which opened in 1999, is planned for westward extension toward La Défense and Mantes-la-Jolie in two phases by 2024–2026. The performance of the RER has made it a model for proposals to improve transit within other cities.[2] In November 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the creation of the additional RERs that will serve the ten largest French metropolises by 2040.[3]

Characteristics

[edit]The RER contains 257 stations, 33 of which are within the city of Paris, and runs over 602 km (374 mi) of track, including 81.5 km (50.6 mi) underground. Each line passes through the city almost wholly underground and on tracks dedicated to the RER, but some city center tracks are shared between line D and line B. The RER is operated partly by RATP, the authority that operates most public transport in Paris, and partly by SNCF, the national rail operator.[4] The system, which is structured in a traditional radial arrangement, operates a through-service and uses a single fare model that works seamlessly with several other public transit systems.[5] Total traffic on the central sections of lines A and B, operated by RATP, was 452 million people in 2006; in the same year, total traffic on all Paris area commuter lines operated by SNCF (both RER and Transilien trains) was 657 million.[6]

RATP manages 65 RER stations, including all stations on Line A east of Nanterre-Préfecture and those on the branch to Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[7] It also operates stations on Line B south of Gare du Nord.[8] Other stations on the two lines and those on lines C, D and E are operated by SNCF. Of the RER stations operated by RATP, 9 have interchanges with Métro lines, and 9 allow transfer to SNCF's Transilien service.[9] In comparison to the Metro, the RER provides better coverage of Paris' suburbs and typically operates at higher speeds and with greater distances between stations.[10] Within the city center, RER services practice limited stop operations.[11]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Its roots are in the 1936 Ruhlmann-Langewin plan of the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (Metropolitan Railway Company of Paris) for a "métropolitain express" (express metro). The company's post-war successor, RATP, revived the scheme in the 1950s, and in 1960 an interministerial committee decided to go ahead with the construction of an east-west line.[12] Subsequently, the central part of the RER was completed between 1962 and 1977 in a large-scale civil engineering project whose chief supervisor was Siavash Teimouri. The construction of the RER was a major undertaking, being highly visible to both Parisians and visiting tourists at various sites across the city for an extended period.[13]

As its instigator, RATP was granted authority to run the new link. The embryonic (and as yet unnamed) RER was not properly conceived until the 1965 Schéma directeur d'aménagement et d'urbanisme (roughly: "master plan for urban development"), which envisioned an H-shaped network with two north-south routes.[14] Between 1969 and 1970, RATP purchased the Vincennes and Saint-Germain lines from SNCF, as the basis for the east-west link.[citation needed] Only a single north-south route crossing the Left Bank has so far come to fruition, although the Métro's line 13 has been extended to perform a similar function.

The RER's first phase of construction during the 1960s and 1970s was marked by scale and expense. In 1973 alone, FRF 2 billion were committed to the project in the budget, equating to roughly €1.37 billion in 2005 terms, and closer to double that as a proportion of the region's (then much smaller) economic output.[15]: 77 The construction cost was controversial at the time of its construction.[16] This initial investment, along with subsequent spending, was partly financed by the versement transport, a local tax levied on businesses that was introduced in July 1971. It has remained in effect into the twenty-first century.[17]

First phase

[edit]During the first phase of construction, the Vincennes and Saint-Germain lines became the ends of the east-west Line A, the central section of which was opened station by station between 1969 and 1977. On its completion, Line A was joined by the initial southern section of the north-south Line B. Both Lines A and B were intentionally designed to converge with as many of the existing commuter lines as possible as to maximise its usefulness to existing travelers.[11] During this first phase, six new stations were built, three of which are entirely underground.

Construction was inaugurated by Robert Buron, then Minister for Public Works, at the Pont de Neuilly on 6 July 1961, four years before the publication of the official network blueprint. The rapid expansion of the La Défense business district in the west made the western section of the first line a priority. Nation, the first new station, was opened on 12 December 1969 and became for the next 8 years the new western terminus of the Vincennes line.[18][12] The section from Étoile (not yet renamed after Charles de Gaulle) to La Défense was opened a few weeks later. It was later extended eastward to the newly built Auber on 23 November 1971, and westward to Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 1 October 1972. The latter extension was achieved by a connection to the existing Saint-Germain-en-Laye line, the oldest railway line into Paris, at Nanterre.[19]

The RER network was inaugurated on 8 December 1977 with the joining of the eastern Nation-Boissy segment and the western Auber-Saint-Germain-en-Laye segment at Châtelet–Les Halles. The inauguration was attended by President Valery Giscard D'Estaing.[16] The southern Ligne de Sceaux was simultaneously extended from Luxembourg to meet Line A at Châtelet – Les Halles, becoming the new Line B. The system of line letters was introduced to the public on this occasion, though it had been used internally by RATP and SNCF for some time.

Second phase

[edit]A second phase of construction commenced at the end of the 1970s, which was carried out at a slower pace than the first phase. SNCF gained the authorisation to operate its own routes, which became lines C, D and E. Extensive sections of suburban tracks were added to the network, but only four new stations were built.[citation needed]

During 1979, Line C (along the Left Bank of the Seine) was added, although it almost entirely comprised existing SNCF lines.[11] The main civil engineering works performed involved the construction of a connecting link between Invalides and Musée d'Orsay.[citation needed] In 1981, Line B was extended through to Gare du Nord via a new deep tunnel from Châtelet – Les Halles. It was later extended further northward.[20][21] By 1992, a total of 233 miles of track was operational, while a further 94 miles were under construction.[11]

During 1995, Line D (north to south-east via Châtelet – Les Halles) was completed; its primary feature was a purpose-built deep tunnel between Châtelet – Les Halles and Gare de Lyon.[22] No new building work was necessary at Châtelet – Les Halles, as additional platforms for Line D had been built at the time of the station's construction 20 years earlier. In 1999, Line E was added to the network, connecting the north-east with Gare Saint-Lazare by means of a new deep tunnel from Gare de l'Est.[citation needed]

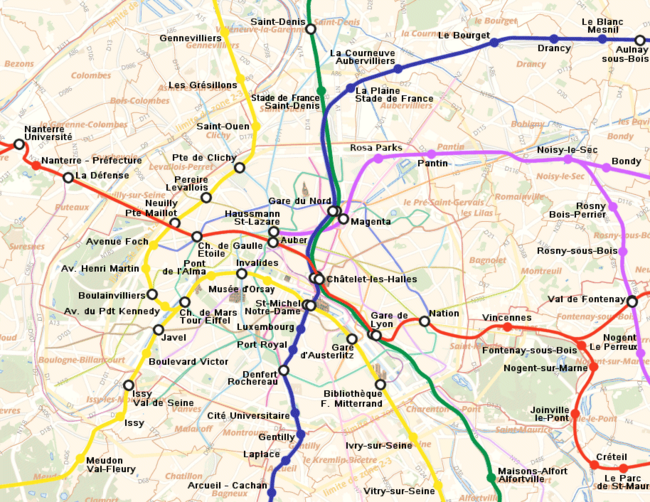

Maps

[edit]

Rolling stock

[edit]The predominance of suburban SNCF track on the RER network explains why RER trains use overhead line power and run on the left, like SNCF trains (except in Alsace-Moselle), contrary to the Métro where trains use third rail power and run on the right. RER trains run by the two different operators share the same track infrastructure, a practice called interconnection. On the RER, interconnection required the development of specific trains (MI 79 series for Materiel d'Interconnexion 1979, and MI 2N series for Materiel d'Interconnexion à 2 niveaux (double-deck interconnection stock)) capable of operating under both 1.5 kV direct current on the RATP network and 25 kV / 50 Hz alternating current on the SNCF network. The MS 61 series (Matériel Suburbain 1961) can be used only on the 1.5 kV DC network.

The RER's tunnels have unusually large cross-sections. This is due to a 1961 decision to build them according to a loading gauge standard created by the Union Internationale des Chemins de Fer (UIC), with space for overhead catenary power supply to trains. Single-track tunnels measure 6.30 m across and double-track tunnels up to 8.70 m, meaning a cross-sectional area of up to 50 square metres, larger than that of the stations on many comparable underground rail networks.[15]: 29

The first RER rolling stock in fact predated the formation of the RER by 40 years, with the Z 23000 stock used on the ligne de Sceaux (which was thereafter integrated into RER B) from 1937 until 27 February 1987. In 1965 the Z 5300 train was introduced, followed by the MS 61 in 1967, MI 79 in 1980, MI 84 and Z 8800 in 1985, Z 20500 in 1988, MI 2N in 1996, Z 20900 in 2001, MI 09 on 5 December 2011, Z 50000 (Francilien) in 2015 and Regio 2N (Z 57000) in 2019. In 2017, it was announced that an consortium comprising Alstom and Bombardier Transportation had been selected to supply 255 X’Trapolis Cityduplex double-deck electric multiple units to replace aging rolling stock on both lines D and E under a €3.75 billion arrangement.[23] In April 2023, 60 additional Cityduplexs were ordered to increase service frequency.[24]

Many services are performed by double-decker train sets, usually operating in double formations.

Lines

[edit]| Line name | Operator | Opened | Last extension |

Stations | Trains in service |

Peak tph | Length | Daily ridership | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RER A | RATP/SNCF[a] | 1977 | 1994 | 46 | 91 | 26 | 109 km (68 mi) | 1,400,000 | |

| RER B | RATP/SNCF[b] | 1977 | 1981 | 47 | 147 | 20 | 80 km (50 mi) | 983,000 | |

| RER C | SNCF | 1979 | 2000 | 84[c] | 172 | 20 | 187 km (116 mi)[c] | 540,000 | |

| RER D | SNCF | 1987 | 1995 | 54[d] | 134 | 12 | 172 km (107 mi)[d] | 660,000 | |

| RER E | SNCF | 1999 | 2024 | 25 | 64 | 22 | 60 km (37 mi) | 350,000 | |

- ^ Most of the line is operated by the RATP, except the Cergy and Poissy branches which are operated by the SNCF

- ^ South of the line (from Châtelet-les-Halles southwards) operated by the RATP, north (from Gare du Nord northwards) operated by the SNCF

- ^ a b Before the section between Epinay-sur-Orge, Massy-Palaiseau, and Versailles-Chantiers was transferred to the T12 and Transilien V.

- ^ a b Within Île-de-France only; full line is 59 stations and 197 km (122 mi).

Stations

[edit]Ten new stations have been built under the heart of Paris since the 1960s as part of the RER project. The six stations of Line A opened between 1969 and 1977 are:

- Nation (1969): deep construction at the Place de la Nation.

- Charles de Gaulle–Étoile (1970): deep construction at the Arc de Triomphe.

- La Défense (1970): near-surface construction beneath the site of the yet-to-be-built Grande Arche de la Défense, just outside the Paris city boundary.

- Auber (1971): deep construction near Gare Saint-Lazare.

- Châtelet–Les Halles (1977): near-surface construction on the site of the former marketplace, claimed in 2017 to be the largest underground station in Europe.[26]

- Gare de Lyon (1977): near-surface construction beneath and alongside the main-line SNCF station.

Some controversy followed the construction of the Line A. Using the model of the existing Métro, and unlike any other underground network in the world, engineers elected to build the three new deep stations (Étoile, Auber and Nation) as single monolithic halls with lateral platforms and no supporting pillars. A hybrid solution of adjacent halls was rejected on the grounds that it "completely sacrificed the architectural aspect" of the oeuvre.[15]: 31 [Notes 1] The scale in question was vast: the new stations cathédrales were up to three times longer, wider and taller than Métro stations, and hence 20 or 30 times more voluminous. Most importantly, unlike the Métro they were to be constructed deep underground. The decision turned out to be expensive: around 8 billion francs for the three stations, equivalent to €1.2 billion in 2005 terms, with the two-level Auber the costliest of the three.[15]: 34 The comparison was obvious and unfavourable with London's Victoria line, a deep line of 22 km (14 mi) constructed during the same period using a two-tunnel approach at vastly lower cost though with a lower capacity. However, the three stations represent undeniable engineering feats and are noticeably less claustrophobic than traditional underground stations.[citation needed]

Only two stations were inaugurated to complete Lines B, C and D:

- Gare du Nord (1982): near-surface construction on two levels.

- St-Michel - Notre-Dame (1988): deep construction on an existing stretch of the Line B between Luxembourg and Châtelet - Les Halles with two tunnels, common in other underground systems but unique in Paris. The station is situated on and built at the same time as the Luxembourg Châtelet tunnel.

Two stations were added to the network as part of Line E in the 1990s. They are notable for their lavishly spacious deep construction, a technique not used since Auber. Although similar to the three 1960s "cathedral stations" of Line A, their passenger traffic has so far proved vastly lower.

- Magenta (1999): deep construction serving both Gare du Nord and Gare de l'Est.

- Haussmann–Saint-Lazare (1999): deep construction serving Gare Saint-Lazare and Auber.

Usage

[edit]

Journey times, particularly on east-west and north-south routes, have been reduced by the RER; in combination with the cross-platform connection at Châtelet - Les Halles, even certain "diagonal" trips have reduced journey times.[citation needed] Typically being used for leisure journeys, the RER has made a significant social impact. By bringing far-flung suburbs within easy reach of central Paris, the network has aided the reintegration of the traditionally insular capital with its periphery. Evidence of this social impact can be seen at Châtelet - Les Halles, whose neighbourhood and Forum des Halles leisure and shopping facilities are popular among banlieusards (suburbanites), in particular from eastern suburbs.[27]

Lines A and B reached saturation relatively quickly, exceeding by far all traffic expectations: up to 55,000 passengers per hour in each direction on Line A (1992), the highest such figure outside of East Asia.[15]: 61 Despite a frequency of more than one train every two minutes, made possible by the installation of digital signalling in 1989, and the gradual introduction of double-decker trains from 1998 to 2017, the central stations of Line A are critically crowded at peak times.[28] In June 2015, a contract valued at €20 million was awarded to Alstom Transport to develop and install an automatic train operation (ATO) system on RER A; at the time, this line was the most heavily frequented regional line in Europe, the introduction of ATO enabled increased service frequency and improved performance to be achieved.[29]

The RER has a substantial impact on the suburban areas of greater Paris, specifically on land values near the stations along its lines.[30] The RER has received criticism for its high level of particle pollution during busy periods, largely due to train braking. Pollution by PM10 particles regularly reaches 400 μg/m3 at Auber,[31] much more than at neighboring metro stations and eight times the EU Commission's daily average limit [32] of 50 μg/m3.

See also

[edit]- List of metro systems

- List of RER stations

- List of Paris Métro stations

- Réseau Express de l'Aire urbaine Lyonnaise

- Transport in France

- Île-de-France tramway Line 11 Express

- S-train

- Réseau Ferré National

Notes

[edit]- ^ Internal RATP journal #226, October 1966

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "La qualité de service du réseau express régional (RER) en Île-de-France" [Île-de-France Regional Express Network (RER) service quality] (PDF). French Court of Accounts 'Annexe n° 1 : consistance et caractéristiques du réseau RER'. October 2023. p. 92.

- ^ "Regional Rail for New York City – Part I". thetransportpolitic.com. 16 July 2009.

- ^ Dailey, Emma (20 January 2023). "12-billion-euro overhaul of major rail hub in France takes shape". railtech.com.

- ^ Blakely 1993, p. 17.

- ^ Blakely 1993, pp. 51, 57.

- ^ Les transports en commun Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, edition 2005-2006, Mairie de Paris.

- ^ "Line A: a priority". RATP. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "New management system for line B". RATP. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Statistiques Annuelles 2006, Départiment Commercial Tarification, Vente Résultats LAC A73 54,quai de la Rapée-75599 Paris

- ^ Rosehill, Harry (27 April 2022). "Railways Around The World That Inspired Crossrail". londonist.com.

- ^ a b c d Blakely 1993, p. 11.

- ^ a b "About us: History". Île-de-France Mobilités. 22 July 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Vitry and Sage 2018, pp. 87-88.

- ^ "Schéma directeur d'aménagement et d'urbanisme de la région de Paris (SDAURP)". institutparisregion.fr. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Gerondeau, Christian (2003). La Saga du RER et le maillon manquant. Presse de l'École nationale des ponts et chaussées. ISBN 2-85978-368-7.

- ^ a b Schofield, Hugh (20 July 2004). "France's answer to Crossrail". BBC News.

- ^ "Versement transport" (PDF). ACGEI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Deep-Level Underground for Paris". The Railway Magazine. No. 826. February 1970. pp. 80–83.

- ^ "The Underground Revolution". Rail Enthusiast. No. 23. August 1983. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "World Update". Railway Age. January 1995. p. 68.

- ^ Dienel 2004, p. 193.

- ^ INA - Report on the new RER D

- ^ Sadler, Katie (11 January 2017). "SNCF selects consortium to supply 255 trains for Île-de-France network". globalrailwayreview.com.

- ^ Booth, Janine (27 April 2023). "Alstom to supply sixty more new-generation trains for Île-de-France". railadvent.co.uk.

- ^ "La qualité de service du réseau express régional (RER) en Île-de-France" [Île-de-France Regional Express Network (RER) service quality] (PDF). French Court of Accounts. October 2023. p. 92.

- ^ "Ouverture de la Porte Marguerite de Navarre, nouvel accès direct à la gare de Châtelet-Les Halles". RATP.

- ^ Large, Pierre-François (2013). Des Halles au Forum: Métamorphose au coeur de Paris. Harmattan. p. 102.

- ^ (in French) SACEM signalling on the French Wikipedia

- ^ Sadler, Katie (11 June 2015). "Automatic train operation to be installed on Line A of Paris RER". intelligenttransport.com.

- ^ European Conference of Ministers of Transport 1980, pp. 44-45.

- ^ "Les données | Plateforme opendata de la RATP". Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ EU Directives 1999/30/EC, Annex III and 96/62/EC, the Air Quality Framework Directive

Bibliography

[edit]- Vitry, Chloé; Sage, Daniel J. (2018). Societies Under Construction. Springer International. ISBN 978-3319739960.

- Blakely, Edward James (1993). Transporting and Transforming a Nation: Issues 584–596. University of California.

- European Conference of Ministers of Transport (1980). ECMT Round Tables Transfers Through the Transport Sector. OECD. ISBN 9282105121.

- Dienel, Hans-Liudger (2004). Unconnected Transport Networks: European Intermodal Traffic Junctions 1800-2000. Campus Verlag. ISBN 359337661X.

Further reading

[edit]- Gaillard, Marc (1991). Du Madeleine-Bastille à Météor: Histoire des transports Parisiens. Martelle. ISBN 2-87890-013-8.

External links

[edit]- RATP (official, in (in French))

- RATP (official, in (in English))

- Interactive Map of the RER (from RATP's website)

- Interactive Map of the Paris métro (from RATP's website)

- Complete track map of the RER system by Franklin Jarrier, 10 November 2015