The Second World War (book series)

This article contains several duplicated citations. (June 2024) |

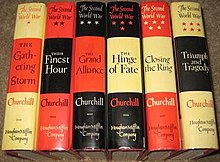

First edition in 6 volumes | |

| Author | Winston Churchill and assistants |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Second World War |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1948–1953 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom[1] |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Liberal Government

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

First Term

Second Term

Books

|

||

The Second World War is a history of the period from the end of the First World War to July 1945, written by Winston Churchill. Churchill labelled the "moral of the work" as follows: "In War: Resolution, In Defeat: Defiance, In Victory: Magnanimity, In Peace: Goodwill".[2] These had been the words which he had suggested for the First World War memorial for a French municipality. His suggestion had not been accepted on that occasion.[3]

Churchill compiled the book, with a team of assistants, using both his own notes and privileged access to official documents while still serving as Leader of the Opposition; the text was vetted by the Cabinet Secretary. Churchill was largely fair in his treatment, but wrote the history from his personal point of view. He was unable to reveal all the facts, as some, such as the use of Ultra electronic intelligence, had to remain secret. From a historical point of view the book is therefore an incomplete memoir by a leading participant in the direction of the war.

The book was a major commercial success in Britain and the United States. The first edition appeared in six volumes; later editions appeared in twelve and four volumes, and furthermore there is also a single-volume abridged version.

Finance

[edit]

Churchill received the first offer for his War Memoirs from a US newspaper syndicate, King Features, at 6.36pm on the day of his resignation as Prime Minister. He initially declined as it would have meant losing his tax status as a "retired author" which exempted his earnings from previous books from the then 90% rate of income tax.[4]

Churchill was eventually tempted in November 1945 by a suggestion from Marshall Field III of the Chicago Sun that he donate his papers to a family trust (thus reducing the impact of high inheritance tax on his children), after which he would only be taxed on his income as "editor" of any book written using them.[5] By February 1946 Churchill's tax advisors had drawn up a detailed plan along these lines. He returned to England in late March from the US, where he had delivered his "Iron Curtain" speech at Fulton, Missouri.[6] In early April he had more meetings with solicitors and tax advisors.[7] On 3 May 1946 Churchill met with Henry Luce and Walter Graebner of Time Life.[8]

Lord Camrose and Emery Reves negotiated further finance deals. Churchill (who despite his large literary earnings throughout his life had been perennially short of money) wanted payment up front, and received £40,000 from Cassells (double what they paid for the History of the English Speaking Peoples which was begun the 1930s but not finished until the 1950s). He probably could have made more had he made a deal for royalties rather than a lump sum. However, lucrative deals were also signed for publication by Houghton Mifflin in the United States, serialisation in Life magazine, The New York Times, in Camrose's The Daily Telegraph in the UK and the Murdoch Press in Australia.[9] Volume 1 was serialised in 80 magazines across the world, and was published in 50 countries in 26 languages.[10] Along with other deals for the publication of his personal papers Churchill appears to have secured around £550,000 (approximately £17 million at 2012 prices). The books made him a rich man for the first time in his life. At the time the salary of the Prime Minister was £10,000 and that of the Leader of the Opposition £2,000.[9]

However Walter Graebner of Life became concerned that insufficient progress was being made over the summer of 1947, during which time Volume One advanced from "Provisional Semi-Final" to "Provisional Final". He bought Churchill a new poodle to replace Rufus who had been run over at the Conservative Party Conference and persuaded his employer to pay for the first of several "working holidays" in the Mediterranean, at a time when British people were only permitted to take £35 out of the country because of exchange controls. The New York Times agreed to share the cost, but Houghton Mifflin declined.[11] After the last of Churchill's expenses-paid working holidays in 1951 (Walter Graebner's suggestions of a final one in 1952 were rejected both by his US Head Office and by Downing Street, as Churchill was Prime Minister again by then), Time Life executives calculated that these had cost $56,572.23 of which Time Life had paid around $35,000 and the New York Times the rest; on the whole they judged this to have been a good investment to get a major writing project finished.[12]

Cassells (who had paid Churchill £40,000 for the entire series) made £100,000 profit from the first volume alone. By 1953 the first five volumes had sold 1.75 million copies in the UK, 1.76 million in the USA and 77,000 in Canada.[13] By April 1954 the six volumes had sold 2.2 million copies in the USA and another 2 million in Britain and the Empire.[14]

Writing

[edit]When Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, he intended to write a history of the war then beginning. He said several times: "I will leave judgements on this matter to history—but I will be one of the historians." To circumvent the rules against the use of official documents, he took the precaution throughout the war of having a weekly summary of correspondence, minutes, memoranda and other documents printed in galleys and headed "Prime Minister's personal minutes". These were then stored at his home and Churchill wrote or dictated letters and memoranda with the intention of placing his views on the record, for later use as a historian. The arrangements became a source of controversy when The Second World War began appearing in 1948. Churchill was a politician, not an academic historian and was Leader of the Opposition, intending to return to office, so Churchill's access to Cabinet, military and diplomatic records denied to other historians was questioned.[15]

It was not known at the time that Churchill had done a deal with Clement Attlee and the Labour government which came to office in 1945. Attlee agreed to allow Churchill's research assistants access to all documents, provided that no official secrets were revealed and the documents were not used for party political purposes.[16] Churchill's privileged access to documents and his knowledge gave him an advantage over other historians of the Second World War for many years.[17][18] The gathered documents were placed in chronologies by his advisers, and this store of material was further supplemented by dictated recollections of key episodes, together with queries about chronology, location and personalities for his team to resolve.[19] Churchill finally obtained Cabinet approval to quote from official documents after negotiations with the Cabinet Secretary Edward Bridges.[20] Churchill also wrote to many fellow actors requesting documents and comments.[19]

The books were largely written by a team of writers known as "The Syndicate". The name comes from horse racing, as Churchill had recently become a racehorse owner.[21] Peter Clarke writes that the Syndicate was run with "businesslike efficiency tempered by the author's whims" by William Deakin. They included Hastings Ismay, Henry Pownall and Commodore Gordon Allen.[22] By February 1946 Churchill's tax advisors had drawn up a detailed plan for his memoirs. Returning to England in late March from the US (where he had delivered his "Iron Curtain" speech at Fulton, Missouri) he engaged William Deakin.[6] Churchill met Deakin on 19 March 1946.[7] In early April, whilst having more meetings with solicitors and tax advisors, Churchill met with Ismay.[7] A year earlier Ismay had sent Churchill a printed copy of the minutes of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council of 1939–40, and in the third week of May Churchill sent him a dictated account of the events leading up to the outbreak of war. Ismay replied with comments and some recollections of his own.[8] By September 1946 Churchill was dictating some chapters on the Battle of France in 1940, which he planned to send to Ismay for comments, whilst warning him that they would be further checked by the "young gentlemen" he would employ, and that they would not be published for several years.[23]

Clarke comments that the books were very much "a collaborative effort", far more so even than Churchill's Marlborough in the 1930s when he had already come to rely heavily on drafts written by specialist researchers. Churchill had the greatest personal input into Volume One.[22] The barrister Denis Kelly was in charge of Churchill's massive personal archive (Churchill would sometimes write on or even chop up documents).[24] Kelly increasingly took on the role of a senior writer.[22] He later recalled bringing proofs from the printers to Churchill at Chartwell in the evenings, to be worked on after dinner late into the night; he would sometimes take instructions from Churchill until after he had climbed into bed, turned out the light and removed his false teeth. He recalled condensing Goodwin's 150 page account of The Blitz down to 3 pages over the course of ten days' work, only for Churchill to sharpen his prose "like a skilled topiarist restoring a neglected and untidy garden figure to its true shape and proportions."[25] Kelly was paid £1,200 per annum over the three year period of 1950–2.[26]

Charles C Wood formerly of Harraps was hired as a proofreader. Sir Edward Marsh also fulfilled that role.[22] Wood, similar in age to Churchill and long retired, was engaged after an early typo that the French Army was "the poop of the French nation". Kelly wrote that this was "too near the truth to let it go" and that after a furious midnight call from Churchill to the publishers errata slips had to be included explaining that the intended word had been "prop"; he commented that it was reminiscent of the newspaper account of Queen Victoria "pissing over Clifton Suspension Bridge to the cheers of her loyal subjects".[25]

The typescript was also vetted by the new Cabinet Secretary, Sir Norman Brook. Brook took a close interest in the books and rewrote some sections to ensure that British interests were not harmed or the government embarrassed.[16] Brook read three successive proofs of Volume One and became in David Reynolds' words almost "an additional member of the Syndicate".[27]

Churchill's personal input into the books declined over time and by 1951 the Syndicate were increasingly writing much of the work in Churchill's style.[28] Peter Clarke uses the phrase "School of Churchill", referring to Peter Paul Rubens' system of delegating much of the work of painting to apprentices and outside experts.[22] Churchill finally released the Syndicate, to whom he had been paying combined salaries of £5,000 per annum, in 1952.[29] Triumph And Tragedy, the final volume, appeared in 1953 after Churchill had once again become Prime Minister, but for appearances' sake it was pretended that Churchill had written it before his return to office in 1951.[22]

Six Volumes

[edit]As various archives have been opened, several deficiencies of the work have become apparent. Some of these are inherent in the position Churchill occupied as a former prime minister and a serving politician. He could not reveal ongoing military secrets, such as the work of the code breakers at Bletchley Park, or the planning of the atomic bomb.[30] As stated in the author's introduction, the book concentrates on the British war effort.[2] Other theatres of war are described largely as a background.[31]

Volume One: The Gathering Storm (covers up to May 1940, published 1948)

[edit]Writing

[edit]Churchill wanted to call the first volume Downward Path but changed the title at the insistence of his US publishers Houghton Mifflin, relayed to him via Emery Reves. Churchill later rejected other advice from Reves, to cut the number of lengthy direct quotes from documents and letters (many of which had been written with a view to eventual publication), and to include more detail in subsequent volumes about his first meetings with Eisenhower and Montgomery (very likely as this would have reduced the emphasis on Churchill's own central role).[32]

In June 1947 while Churchill was recovering from a hernia operation the Daily Telegraph gave permission to extend the book from 4 volumes to 5 (it would run to 6 in the end).[33] Volume 1 was largely completed by July 1947. Daniel Longwell of Life Magazine spent a month in England, making various suggestions for changes, most of which were accepted.[34] In November 1947 Henry Luce complained that the book contained too many lengthy quotes from documents.[35] Churchill had the first of several holidays, paid for by his publishers, at Marrakesh in December 1947.[36]

Before publication, at the urging of his son-in-law Christopher Soames he toned down a reference to the Polish seizure of Teschen from Czechoslovakia after Munich being "baseness in almost every aspect of their collective life" to "faults in almost every aspect of their governmental life".[37] Churchill's comment that "the heroic characteristics of the Polish race must not blind us to their record of folly and ingratitude...the Poles were glorious in revolt and ruin; squalid and shameful in triumph [over Czechoslovakia in 1938-9]" was given wide publicity by the Communist government in Warsaw as an example of the anti-Polish feelings of British leaders.[38] The comments also annoyed Polish American opinion, as did another about Poland "grovelling in villainy", and were cut from the British edition.[39]

The Gathering Storm began to appear serialised in the newspapers in April 1948 just as the Soviets were suppressing Czechoslovakia and was published in book form in June and July as the Berlin Blockade began.[40] The Gathering Storm was published in the USA on 2 June 1948.[41] The message of 'the book was that appeasement of dictators always leads to war as they escalate their demands in response to concessions, and Churchill made it quite clear in several speeches in 1948 that he was referring to Stalin as much as Hitler.[42]

An early draft of Volume One had conceded that there "may be some substance" to the argument that the Ten Year Rule, still in force during Churchill's chancellorship (1924–29), had slowed defence research and long term planning. This was amended to stress that the rule was laid down by the Lloyd George government in 1919 and had the backing of the Cabinet and Committee of Imperial Defence. Churchill argued that he was not wrong to have kept the Rule in place until 1929, as war did take another ten years to break out, and he argued that Hitler could have been stopped without loss of life up to 1934 when he had started building the Luftwaffe. Former Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey wrote in protest to The Times (31 Oct 1948) arguing that even after its repeal the Ten Year Rule had cast a baleful influence over defence planning. Hankey had a testy public exchange of letters with Churchill's assistant General Ismay, who wrote that it was unfair to blame Churchill for actions of governments when he was out of office after 1929. Hankey's final letter (20 Nov 1948), which The Times declined to publish, argued that Churchill's rearmament campaign in the 1930s had served merely to cause public dismay and encourage Hitler. Hankey prepared, but did not complete, a longer critique of Churchill's interwar influence. He sent material to Viscount Templewood (the former Sir Samuel Hoare) whose memoirs were published in 1954.[43]

After publication Noël Coward complimented Churchill on his "impeccable sense of theatre", eg. describing his last meeting with Joachim von Ribbentrop in 1938 as "the last time I saw him before he was hanged".[44]

Analysis

[edit]British historian David Reynolds noted that in Volume One, The Gathering Storm, Churchill skipped over the 1920s as his actions then did not support his self-image as a leader who was far-sighted about the Axis threat. Churchill criticised the "follies" of the victors of 1918 in drafting the Treaty of Versailles, which he viewed as too harsh towards Germany, but then contradictorily defended the Treaty's disarmament clauses on the grounds that if the Reich had remained disarmed, the Second World War would never had happened.[45] Churchill defended the foreign policy of the Second Baldwin ministry-of 1924 to 1929 in which he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer and-which sought to promote peace by revising the Treaty in favour of Germany.[46] Reynolds noted that Churchill did not mention that as Chancellor he had fought for greater social spending to combat the appeal of the British Communist Party to the British working class by cutting defence spending.[47] In the decade or so after the Russian Revolution, Churchill saw Soviet Russia as the principal enemy, but he viewed the Soviet challenge to Britain as ideological, not military. In December 1924 Churchill told the prime minister Stanley Baldwin at a cabinet meeting: "A war with Japan! I do not believe there is the slightest chance of that in our lifetime" and he argued that the Royal Navy budget should be cut as Japan was the only naval power capable of challenging Britain in Asia and that the reduced expenditure should be used for social programmes.[47] Churchill portrayed the 1929 United Kingdom general election, which was won by the Labour Party under Ramsay MacDonald, as the moment that British foreign policy went off the rails.[46] Reynolds noted that Churchill portrayed himself in The Gathering Storm, as being in the political "wilderness" in the 1930s because of his prescient opposition to the appeasement of Nazi Germany, but the real reason was that in Opposition in 1930–1931 he had led a backbenchers' rebellion trying to topple Baldwin (who supported Indian self-government) as Conservative leader; this disloyalty led to his exclusion from the National Government formed in 1931. He was later absolutely opposed to the Government of India Act 1935 which devolved much power to the Indians as a preparatory step towards ending the British Raj.[48]

Churchill portrayed Anthony Eden – who served twice as his Foreign Secretary in 1940–1945 and again in 1951–1955 – as an especially noble anti-appeaser when in fact he had regarded Eden in the 1930s, including his first time as Foreign Secretary between 1935 and 1938, as both an excessively ambitious political lightweight with bad judgement and until 1938 as an appeaser.[49] Churchill portrayed Eden's resignation from the Chamberlain cabinet in February 1938 as the decisive turning point under which the appeaser Lord Halifax became Foreign Secretary.[49] This account was written to please Eden, who had been Churchill's "heir apparent" since 1940, and who wanted to be remembered as an anti-appeaser who had resigned in protest against Neville Chamberlain's foreign policy.[50] In fact at the time Churchill did not regard the appointment of Halifax as an important change.[51] In the late 1940s as he waited with barely veiled impatience for Churchill to retire as Conservative leader Eden wanted to airbrush the fact that he had very much liked and admired Adolf Hitler on first meeting him in 1935 and felt Hitler's foreign policy was limited to revising the Treaty of Versailles. However Eden had favoured a tougher line against Benito Mussolini, whom he detested as much as liked Hitler, and it was foreign policy disagreements over Italy, not Germany, that prompted his resignation from the cabinet in February 1938.[51]

Churchill had a strong belief in the power of strategic bombing to win wars and in a speech in the House of Commons on 28 November 1934 he had predicted that Luftwaffe strategic bombing of London would kill between 30,000 and 40,000 Londoners in the first week. In July 1936 he claimed that a single Luftwaffe bombing raid on London would kill at least 5,000 people.[52] In reality, German strategic bombing of British cities killed or wounded about 147,000 people between 1939 and 1945 and the major problem was not people being killed, but rather the homelessness caused by the destruction of houses and flats.[52] Churchill admitted in The Gathering Storm that in the 1930s he had made exaggerated claims about the killing capacity of Luftwaffe strategic bombing to spur the government to spend more on the Royal Air Force (RAF).[52] David Dutton wrote that the popular image of British politics in the 1930s is of an epic feud between Churchill the anti-appeaser and Chamberlain the arch-appeaser, but the real target in The Gathering Storm is not Chamberlain, but rather Baldwin, a man whom Churchill greatly hated.[53] The "Churchill Camp" of anti-appeasers consisted of Churchill, Brendan Bracken, Admiral Roger Keyes, Lord Lloyd, and Leo Amery, and because it was so small Chamberlain did not consider it a threat to his ministry. Dutton noted that Churchill was much more critical of Baldwin, who after the failed attempt to depose him in 1930–1931 always made it clear that he would never allow Churchill to serve in the cabinet again, than of Chamberlain who allowed Churchill to join his cabinet on 3 September 1939 as First Lord of the Admiralty (his old job from 1911–1915), despite the popular perception that Churchill had a chequered record as a politician associated with failures, most notably the Gallipoli campaign in 1915.[53] This gave Churchill's career a major boost, and it was the perception that Churchill was a successful First Lord of the Admiralty in 1939–1940 that allowed him to become Prime Minister on 10 May 1940.[53] In The Gathering Storm, Churchill turned Baldwin "man of Middle England" image against him to devastating effect as he portrayed Baldwin as a petty and provincial politician unfit to be prime minister.[53] As Conservative leader, Baldwin had been often been photographed in rural settings, dressed as a squire and smoking his pipe, to associate him with rural England, a positive image that Churchill turned into a negative one by writing that Baldwin was too provincial to conduct a proper foreign policy.[53] Dutton wrote that the popular belief that Churchill became Prime Minister in May 1940 because he was an anti-appeaser is not true, and the real reason was the widespread belief that the failure of the Norway expedition proved Chamberlain to be an unsuccessful war leader while Churchill was seen as the best man to win the war. Appeasement only started to be seen as a disastrous foreign policy after the publication of the best-selling book Guilty Men in early July 1940.[54]

In the chapter on the development of radar, Churchill downplayed the role of Sir Henry Tizard while playing up the role of his science adviser Lord Cherwell, aka "The Prof".[55] Churchill wrote that Tizard sacked Cherwell from the Scientific Air Defence Committee in 1937 for being Churchill's friend, but in reality it was for his impassioned advocacy of the impractical weapon of "aerial mines", which made Cherwell a disruptive force on the committee.[56] Cherwell served as Churchill's science adviser throughout the war, and Churchill found it embarrassing that some of his ideas were those of a crank.[57] In a note he sent to research assistant Bill Deakin on 30 June 1947, Churchill asked: "Surely there was some fighting in 1931 between Japan and China?"[58] Churchill gave only very brief mentions of the crisis in Asia caused by Japan's invasion of China in 1937 along with increasingly strident Japanese claims that all of Asia should be in their sphere of influence, which gave a distorted picture of British politics as Neville Chamberlain's government was very concerned that Japan might use a war in Europe to seize Britain's Asian colonies.[58] Despite support for strategic bombing Churchill, judging by his "Memorandum on Sea-power" written on 25 March 1939, did not see air attacks on ships as a major danger. He also wrote that any threat from submarines had been "mastered".[59] The major theme in Churchill's memo which was based on his previous experience as First Lord of the Admiralty (1911–1915) was that naval warfare would be decided by traditional battleship gunnery duels. Churchill also assumed that Italy would enter any war on the German side and argued that the Royal Navy should concentrate in the Mediterranean at the expense of Asia. Churchill assumed that Japan would enter the war on the Axis side, but dismissed the need to activate the Singapore strategy as they could never take Singapore.[59] Churchill printed the "Memorandum on Sea-Power" in The Gathering Storm, but cut out the parts where he wrote that Singapore would be "easy" to hold against the Japanese; that there was no threat from U-boats to British shipping; and that Axis aircraft were not capable of sinking British warships.[60]

Reynolds also noted that Churchill's picture of the Soviet Union varied depending on the politics of the moment. In The Gathering Storm which was published in 1948 (before the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb), Churchill portrayed the Soviet Union as little better than the Axis states as reflected in his account of the Spanish Civil War which portrayed the Republicans and Nationalists as equally savage and deserving of condemnation.[61]

Churchill's account reflected his strong view that it would have been better for Britain to have gone to war for Czechoslovakia during the 1938 Sudetenland crisis rather than for Poland during the 1939 Danzig crisis. Reynolds noted that "many historians" tended to agree with Churchill.[62] During the Danzig crisis Churchill also believed that a "Grand Alliance" of Britain, France and the Soviet Union would have deterred Hitler from invading Poland, and in The Gathering Storm he strongly criticised Neville Chamberlain for not trying harder to reach a Soviet alliance and for believing that Poland was a stronger ally than the Soviet Union.[62] The principal problem during the "peace front" talks in 1939 was that the Poles absolutely refused to grant the incessant Soviet demands for Red Army transit rights into Poland. Reynolds noted that during the Danzig crisis British leaders first confronted in embryonic form the problem that it was not really possible to be an ally both of Poland and the Soviet Union, a recurring problem during Churchill's wartime premiership.[62]

Reviewers noted that Churchill, reflecting the "Great Man" view of history, gave readers the picture of "an almost stationary world upset by the wild ambitions of a few wicked men" such as Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, which also reflected the politics of the Cold War. Churchill saw the Soviet Union as the principal enemy and West Germany, Italy and Japan as British allies, which led him to portray the origins of World War Two in very personalised terms. Churchill wrote in an almost admiring tone that Mussolini was one of the exceptional leaders able to bend history to his will, and portrayed Il Duce as a man who perverted Italian politics by preventing the "normal" course of Italian history from occurring.[63] Likewise, Churchill portrayed Hitler very much as a "Great Man" able to bend history to his will owing to his determination and intelligence, which suggests that Nazism was only Hitlerism, and that if Hitler had never lived, German history would have continued on as "normal".[64] Churchill tended to downplay continuities in German history such as the imperialistic Second Reich war aims towards both Western and Eastern Europe in the First World War and the Weimar Republic's absolute refusal to accept the borders with Poland imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. In the Cold War, Churchill supported West German rearmament as an ally against the Soviet Union and he portrayed the Wehrmacht in a relatively favourable light.[65] Another reason for Churchill portraying the Wehrmacht generals more as victims than followers of Hitler was his claim that if only he had been prime minister in 1938, the Second World War would have been avoided altogether. He presented as fact the self-serving claims made by Wehrmacht generals after 1945 that during the 1938 Sudetenland crisis they would have staged a military coup to overthrow Hitler, which was prevented by the Munich Agreement. Churchill was informed by his researchers that these claims were dubious at best, and were clearly meant to be a rationalisation for serving the Nazi regime by blaming the British and French governments.[66]

In his coverage of the Norwegian campaign Churchill accepted the criticism that the Admiralty had been wrong to force Admiral Forbes to cancel his attack on the German fleet at Bergen shortly after the invasion.[67] During that campaign, which led to Chamberlain's fall from power, Churchill was seen as a dynamic war leader by the public, even though many senior political and naval colleagues took a dimmer view of his competence. In an early draft he had written "it was a marvel – I really do not know how – I survived and maintained my position in public esteem while all the blame was thrown on poor Mr Chamberlain". This was excised from the published edition.[68][69] Churchill's conduct of the campaign was later attacked by Stephen Roskill in the Official History of the Second World War in 1954, although Churchill deferred to the advice of Commodore Allen and Norman Brook not to press for changes.[70]

Churchill's account of how he became Prime Minister is inaccurate. Deakin took the blame for misdating the meeting of Chamberlain, Halifax and Churchill and omitting the presence of Chief Whip David Margesson. Jonathan Rose suggests that Churchill may have deliberately embellished the story by omitting the presence of Margesson, exaggerating the length of a pause when Halifax declined to accept the premiership (other accounts suggest that Churchill may have been more aggressive in stating that he did not believe Halifax should be Prime Minister) and timing the meeting to coincide with the German attack on the Low Countries (in fact Chamberlain briefly tried to rescind his resignation, agreed the previous day, when the attack began).[71][72]

Volume Two: Their Finest Hour (covers 1940, published 1949)

[edit]Writing

[edit]Churchill was briefly at a low ebb in June 1948 and asked his solicitor to check the contract to see if he could step down as the notional author of the work. The mood passed, helped in part by another "working holiday" in the South of France, once again paid for by Life and the New York Times.[73] Churchill worked in the South of France in late August 1948.[74] Deakin helped Churchill with Volume Two in France in summer 1948, and a "starred final" version was ready for the printers after his return to Britain. Another working holiday, this time in Monte Carlo, was arranged for that winter.[75]

The first draft of Volume Two included an account of the intense debate within the Cabinet between 26 and 28 May 1940, in which Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax argued that Britain should use Mussolini as an "honest broker" to make peace before France was defeated. The Labour leaders Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood rejected Halifax's approach, and were joined by Chamberlain. Churchill accused Halifax of being willing to "buy off" Mussolini by ceding to Italy Gibraltar, Malta and the Suez Canal and praised Chamberlain and Attlee as "very stiff and tough" in rejecting Halifax's suggestions. He did not mention his own statement to Halifax on 26 May that "if we could get out of this jam by giving up Malta and Gibraltar and some African colonies he would jump at it", though he went on to say that he doubted that it was possible to make any sort of reasonable peace with Hitler who had no reason to make concessions with Germany winning the war. Churchill ultimately dropped all references to the debate while mentioning that French Prime Minister Reynaud was willing to make concessions to Mussolini in exchange for brokering peace.[76]

In June 1950, the year after publication, Churchill agreed to tone down criticism of the Italian invasion of British Somaliland in August 1940, which he described as "our only defeat at Italian hands". This was at the request of Major General Chater who blamed the collapse of the Vichy French in French Somaliland and late approval of his defence plans by the War Office and Colonial Office. Churchill agreed to amend subsequent editions.[77]

Analysis

[edit]Reynolds noted that in Their Finest Hour Churchill sometimes engaged in national stereotypes. In his account of his summit with the French Premier Paul Reynaud on 16 May 1940, Churchill portrayed Reynaud along with Maurice Gamelin and Édouard Daladier as hopelessly defeatist figures, reflecting the faiblesse of France in contrast to the fighting spirit and courage of the British.[78] Reynolds noted that the actual transcript of the summit showed that Gamelin was indeed depressed as Churchill portrayed him, but that Reynaud and Daladier-though worried by the German victory in the Second Battle of Sedan-were nowhere near as defeatist as Churchill portrayed them.[78] Reynaud wrote a lengthy reply in The Daily Telegraph and The New York Times challenging Churchill's account of the meeting on 16 May 1940, stating that Churchill made him like the rest of the French cabinet appear very defeatist.[79] Churchill did not mention the intense debate within the Cabinet between 26 and 28 May 1940 where the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax argued that France would soon be defeated and that Britain should use Mussolini as an "honest broker" to negotiate peace, but mentioned that Reynaud was willing to do so, thereby contrasting the supposedly craven and cowardly French and the stout and stalwart British.[80] British historian Max Hastings noted that Churchill downplayed his own importance in seeking to continue the war in 1940. The picture that he painted of a British people solidly united under his leadership for victory over Nazi Germany was not true, and in May–June 1940 much of the British aristocracy including the Duke of Westminster and Lord Tavistock along with a number of MPs including former prime minister David Lloyd George thought that the Reich was invincible and favoured making peace while there was still time. Hastings wrote that the principal difference between the British and French experiences of the war in 1940 was that in France leaders such as Marshal Philippe Pétain, Pierre Laval, and General Maxime Weygand actually did sign an armistice with Germany.[81] Churchill also gave the misleading impression that in 1940 he wanted to fight on until the total destruction of Nazi Germany while in fact he was open to a negotiated peace provided Hitler was overthrown.[82][83] Churchill did not mention his 4 September 1940 memo arguing that strategic bombing would so damage the German economy that the Wehrmacht generals would overthrow Hitler to make a favourable peace with no need for major land battles, just as in 1918 Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Wilhelm Groener had forced the Emperor Wilhelm II to abdicate in order to make a peace which limited but not destroy German power.[84]

Churchill did not mention the crisis in July 1940 caused by the Japanese demand that Britain close the Burma Road, which linked India to China and was the principal means by which arms reached China.[85] Lord Halifax wanted to reject the Japanese ultimatum and risk war with Japan while Churchill wanted to give in and close the Burma Road, saying that with Germany on the brink of invading Britain that this was no time for a war with Japan.[85] A compromise was crafted and Britain closed the Burma Road until October 1940 over furious Chinese protests and adverse American comments.[85] Churchill also did not mention his belief in 1940 that the pro-Allied neutrality of President Franklin D. Roosevelt meant that the United States would enter the war later in 1940, which did not happen.[86] Churchill's contacts in the United States were mostly with Anglophile upper-class, WASP "Eastern Establishment" Americans who had been educated at elite universities like Harvard, Yale and Princeton and were unrepresentative of the broader American public.[87] Churchill wrongly assumed in 1940 that most Americans were Anglophiles who would be so outraged by the German bombing of the British cities that public pressure would force Congress to declare war on Germany before the presidential election due in November of that year.[87]

Most of the chapter on the Battle of Britain was based on a short book entitled The Battle of Britain by Albert Goodwin that was published in March 1941 by the Air Ministry and sold over a million copies in the first week after its publication.[88] In that chapter Churchill celebrated "the few" as he called the pilots of RAF Fighter Command, but said almost nothing about their commander Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding.[89] Churchill insisted that he sacked Dowding in November 1940 only reluctantly and blamed the civil servants of the Air Ministry.[89] Dowding was a shy, modest man virtually unknown to the British people during the Battle of Britain, and his sacking had attracted little media attention. It was after 1945 that Dowding came to be celebrated as a "quiet hero", hence Churchill's defensive tone about why he sacked him.[89] In fact, Churchill had sacked Dowding because he believed that the narrow victory won by the Fighter Command was a sign of incompetence. Dowding's repeated statements during the Battle of Britain that the Luftwaffe was killing Fighter Command pilots faster than the Training Command could produce new pilots were viewed by Churchill at the time as a sign that Dowding was not fit to command. A key moment in Their Finest Hour is the account of a meeting with Air Marshal Keith Park who commanded the Number 11 Group of Fighter Command that covered south-eastern England on 15 September 1940.[90] He claimed that he asked the same question of Park that he had asked of Gamelin on 16 May 1940 "where are the reserves?" and in both cases received the answer that there were none; in a contrast to Gamelin who was portrayed as broken and defeated, Park was portrayed as unbowed and determined.[90] The same point about the French as useless allies is driven home by the contrast between the French using obsolescent technology which features prominently in the account of the meeting on 16 May and Fighter Command which was using highly advanced aircraft such as the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire in the meeting on 15 September.[90] Churchill downplayed the importance of radar in the Battle of Britain largely because it was the Chamberlain government that had built the network of radar stations, but devoted an entire chapter to "The Wizard War".[89] "The Wizard War" celebrated two young British scientists, R.V. Jones and Albert Goodwin, as the scientific "wizards" who had "broken the beams" (the radio beams that guided German bombers onto British cities) that was largely based upon notes from Goodwin and Jones.[91] The portrayal of Jones and Goodwin as "wizards", rhetoric that invoked magic and sorcery revealed much about Churchill's attitude towards science. When Italy invaded Greece on 28 October 1940, Churchill portrayed the opposition of Wavell to sending forces to Greece as a misunderstanding as he claimed he was unaware that Wavell had a plan for an offensive intended to stop the Italian invasion of Egypt and push into the Italian colony of Libya.[92] In fact, Churchill was informed on 3 November 1940 of Wavell's plans, but in order to gain the War Cabinet's approval to send forces to Greece on 4 November he did not tell them about Wavell's plan until 8 November.[93]

In the chapters on the Middle East, Churchill initially wrote that he wanted to arm the Jews of the Palestine Mandate (modern Israel), but was blocked by Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, who commanded the Commonwealth forces in the Middle East.[94] The first draft included the line: "All our military men disliked the Jews and loved the Arabs. General Wavell was no exception. Some of my trusted ministers like Lord Lloyd and of course, the Foreign Office, were all pro-Arab if they not actually anti-Semitic".[95] Sir Norman Brook told Churchill to delete that sentence, saying it was not helpful towards Britain's image in the Middle East.[96] Churchill wrote in Their Finest Hour that he wanted to sack Wavell as Middle East commander-in-chief in the summer of 1940 and to replace him with one of his favourite generals, Bernard Freyberg of New Zealand.[94] Only the objections that Freyberg, who had never commanded anything larger than a division, did not have the personality for high command led him to retain Wavell despite his lack of confidence in him.[94] An entire chapter is devoted to Churchill's decision in August 1940 to send 154 tanks,-which were half of the entire tank force in the United Kingdom,-to Egypt (which Italy had invaded) through the shorter and more dangerous route through the Mediterranean rather the longer and more safer route via the Cape of Good Hope.[96] Churchill wrote correctly that the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, thought the Mediterranean route was too dangerous, but he did not mention in the final draft the idea originated with the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir John Dill.[94] The first drafts had mentioned Dill's role, but Eden who was serving as the War Secretary at the time wanted to share credit for the bold decision to send the tanks to Egypt, and had Dill's role eliminated.[95]

Churchill mentioned in Their Finest Hour that he tried to bring his old mentor in politics, David Lloyd George, into his cabinet as an elder statesmen, but he did not mention that Lloyd George refused his offer because he expected him to lose the war.[97] Lloyd George had met Hitler several times in the 1930s, and he believed that he had a special rapport with Hitler that would allow him to negotiate a favourable peace with Germany. As late as October 1940, Lloyd George was predicting that Britain would soon be defeated as he expected Churchill to fail as prime minister and that King George VI would be forced to make him prime minister again with a mandate to make peace.[98] Churchill did admit that his position as prime minister was precarious for much of 1940 as he took over the leadership of the Conservative Party in October 1940 when Chamberlain resigned owing to the bowel cancer that would kill him within a month.[98] Churchill wrote that whoever led the Conservative Party would be the real leader of the country, and that he had "only executive responsibility" as prime minister without being the Conservative party leader.[98] Churchill did not mention that his real concern was that Lord Halifax would succeed Chamberlain as Conservative leader and that he wanted Halifax out of his cabinet as he believed that Halifax would bring him down as prime minister sooner or later.[98] The opportunity finally came in December 1940 when Lord Lothian the British ambassador to the United States died, leading to Churchill to appoint Halifax as the new ambassador in Washington and make Eden his new Foreign Secretary.[98] Besides the removal of a rival, Churchill felt that Eden as Foreign Secretary would be more capable than Halifax of executing the foreign policy he wanted to see.[98]

Volume Three: The Grand Alliance (covers 1941, published 1950)

[edit]Writing

[edit]In May 1949 Churchill wrote to Deakin that he had largely finished Volume 3.[99] In July 1949 Pownall wrote to him that he had spent some time with Field Marshal Wavell going through the parts of Volume 3 which concerned him. Wavell commented that "on the whole [Churchill] has been very kind to me".[100]

In the summer of 1949[101] Churchill had another working holiday on Lake Garda in Italy. He had planned to work on Volume 4 but was delayed by criticism from the US publishers that the Volume 3 draft contained too much detail about British campaigns in the Mediterranean. Reves urged him to discuss his top-level talks with Roosevelt. Churchill had a mild stroke at Max Beaverbrook's villa in the south of France and had to be rushed home privately.[102] By autumn 1949, with a General Election looming, Churchill was conducting sporadic work on Volume 4 while still polishing Volume 3. Another working holiday was planned for late in the year but once again his interest was flagging. He had a discussion with Camrose of the Daily Telegraph about appointing Duff Cooper as a possible replacement as writer-in-chief of the work, but nothing came of this.[103]

In October 1949 Pownall and Kelly incorporated comments by the New Zealand War Historian on the Crete campaign and Cunningham the who criticised Churchill's account of the bombardment of Tripoli, but otherwise thought the book "a fair picture of the doings of the Fleet". The US publishers complained once again about too many long quotes from minutes and his wife Clementine complained at dinner in front of Walter Graebner thar "I got so tired of the endless detail about unimportant battles and incidents. So much of the material is pedestrian".[104] Clementine persuaded him to tone down some criticism of the Royal Navy.[105]

Dutch opinion was angry at Churchill's failure to mention the activities of their submarines in the Far East in December 1941 (under the command of Conrad Helfrich), so he agreed to include a footnote in the Dutch edition of Volume 3. Michael Foot reviewed Volume 3 to say that when Barbarossa had been launched in June 1941 Churchill like many others had "grossly under-estimated the Russian powers of resistance" and it was "a downright falsehood" to claim otherwise. Churchill's former Assistant Private Secretary Jock Colville provided oral testimony that whereas CIGS John Dill and US Ambassador Winant had both thought that the Soviets would be lucky to last six weeks Churchill had been willing to bet "a Monkey to a Mousetrap" (£500 to £1 or a sovereign) that the Soviets would be fighting victoriously in two years' time. Colville commented "So much for Michael Foot".[106]

Analysis

[edit]In order to uphold the unity of the Commonwealth, Churchill did not mention that he had serious disagreements about strategy in the first half of 1941 with the Australian prime minister Robert Menzies and the New Zealand prime minister Peter Fraser, both of whom had major doubts about the wisdom of dispatching Australian and New Zealand soldiers to the defence of Greece in 1941.[107] Menzies and Fraser both paid an extended visit to London in early 1941 to debate strategy with Churchill; Menzies's visit was only briefly mentioned while Fraser's visit was not mentioned at all.[107] Churchill defended the decision to send an expedition to Greece on the grounds that it could have changed the course of the war by allowing British bombers to use Greek airfields to reach Romanian oil fields which supplied most of the oil used by the Wehrmacht.[108] Churchill mentioned that he sent Eden on a visit to Turkey in January 1941 where he reported that President İsmet İnönü might be open to joining the war on the Allied side, which led Churchill to hope for a league of Turkey, Greece and Yugoslavia which would tie down the Wehrmacht in the Balkans.[108]

Churchill was sensitive to the charge made by General Francis de Guingand in his 1947 memoirs that the Greek expedition had weakened the British offensive into Libya and thereby ended the chance to clear the Italians out of Libya before the arrival of the Afrika Korps.[109] Menzies during his lengthy visit to London between 20 February and 20 May 1941 found himself playing devil's advocate as he questioned the assumptions behind the Greek expedition.[110] Menzies thought that using Greek airfields to bomb the Romanian oilfields was a good plan, but pointed out that Hitler would reach the same conclusion and would invade Greece to thwart it. Churchill did not mention that Menzies thought that the forces being dispatched to Greece were not strong enough to hold out against the expected German invasion, giving the impression that no arguments were made against the Greek expedition.[110] The fact that Churchill was not allowed to mention the Ultra programme did not allow him to defend himself from one of the charges made against him, namely that by sending the Australians and New Zealanders to Greece, he weakened the Commonwealth forces in Libya and Egypt.[111] Churchill's assumption that he could pull forces out of North Africa to defend Greece was based upon his reading of the German codes and of Hitler's orders to Erwin Rommel of the Afrika Korps to stay on the defensive in Libya; he did not anticipate that Rommel, gambling that Hitler would not punish him for a successful offensive, would launch an unauthorised offensive which pushed the Commonwealth forces back to the Egyptian frontier.[111] The chapter on the Battle of Crete was heavily based upon notes written by Bernard Freyberg who commanded the defence of Crete, where Freyberg presented the battle as a hopeless, but noble struggle, which thereby covered up the fact that Freyberg had ignored intelligence that the Germans were planning to invade Crete via the air instead of the sea as he expected.[112] Wavell had informed Freyberg of the Ultra secret just before the Battle of Crete and told him of the three airfields where the German paratroopers were going to drop, but also told him not to change the disposition of his forces as that might tip the Germans off that the British were reading their codes.[113] Freyberg believed that Crete was not very important and was not informed that Hitler was obsessed with the fear that British bombers based in Crete would destroy the Romanian oilfields upon which the Reich depended, a point he impressed on Churchill in his letters to him.[114] Churchill made much of the Pyrrhic victory won by the Germans in the Battle of Crete as the elite Paratroop Corps was badly mauled by the ferocious resistance of the Anglo-Australian-New Zealander-Greek defenders, but exaggerated the losses suffered by the Paratroop Corps.[115] Churchill claimed 15, 000 German dead while in reality the Paratroopers lost only 5, 000 dead.[115]

Churchill was dissatisfied with Admiral Andrew Cunningham's apparent reluctance to attack Tripoli in April 1941, which Churchill wanted him to do to stop supply of Rommel's forces from Italy. Admiral Dudley Pound suggested using HMS Centurion, used as a target ship since the 1920s, as a sacrificial blockship. The next day the Admiralty ordered Cunningham to sacrifice HMS Barham and a light cruiser; Cunningham thought this a waste of two good ships and their crews, as the Axis had already landed a lot of supplies and could land more through Vichy French Tunisia. Instead he obtained permission to bombard Tripoli on 21 April 1941 but warned that future attempts might not be so successful if the Luftwaffe was active in the area, and preferred that Tripoli should be bombed by air from Egypt. Churchill deferred to his judgment, although Pound suggested stationing an old battleship at Malta to disrupt Axis convoys from Italy to Libya. Jock Colville (25 May 1941) recorded Churchill saying that Cunningham should be willing to lose half the Mediterranean Fleet to save Crete. Off Crete Britain lost three cruisers and five destroyers with two battleships, one aircraft carrier, eight cruisers and seven destroyers damaged.[116] Churchill also did not mention the memo he received from Cunningham after the Battle of Crete in May 1941 saying he never wanted to have Royal Navy warships without air cover again, and that the losses taken by the Royal Navy off Crete due to German and Italian aircraft were unacceptably high, very likely as it would have invited criticism of his deployment of capital ships to Singapore, where they were sunk by Japanese aircraft in December.[117] Fortunately Luftwaffe aircraft were diverted to the Russian Front in the latter part of 1941 and a force of light cruisers and destroyers was able to be deployed to Malta; Churchill still felt that Cunningham was insufficiently aggressive but by November was distracted by the Operation Crusader battle in the desert.[118]

In contrast to his favourable treatment of Freyberg, Churchill made it clear that he regarded Wavell as incompetent. Churchill came close to accusing Wavell of cowardice as he wrote he had to push Wavell into invading the colony of Italian East Africa (modern Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea).[115] Churchill wrote that Wavell did not want to take action about the campaigns in Iraq and Syria, and that he to push him into action.[119] By splitting the campaigns that involved Middle East Command into different chapters, Churchill downplayed the immense problems faced by Wavell who was in charge of campaigns in Egypt, Ethiopia, Crete and Iraq all at the same time.[119] Churchill wrote that the British had a spy in the Afrika Korps and as such there was no excuse for Wavell's defeat in Operation Battleaxe in June 1941, for which Churchill sacked him.[120] There was no such spy, but Churchill could not mention the secret Ultra intelligence; however, it is true that Churchill sacked Wavell believing that he should have been victorious given his intelligence advantage.[120]

The chapter "The Soviet Nemesis" about Operation Barbarossa featured a lengthy attack on the "error and vanity" of Joseph Stalin in ignoring repeated British warnings that Germany was going to invade the Soviet Union in the spring of 1941.[121] On 14 May 1941, the Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess flew to Scotland to propose peace.[122] Churchill had prepared a statement to the House of Commons saying that the British government was not interested in talking to Hess, but upon the advice of Eden he did not deliver it.[123] Eden thought it best to leave the impression that Britain might be willing to take up Hess on his eccentric peace mission as a way to blackmail the United States into providing more aid.[123] Churchill did not mention that he followed Eden's advice, which had the opposite effect from the one intended, not the least because Stalin thought that Britain was trying to make peace and took the British warnings about Operation Barbarossa as a part of an Anglo-German plot.[123] However, Stalin had already long decided before Hess made his flight that Germany was not going to invade the Soviet Union. In The Grand Alliance, the image of the Soviet Union that Churchill painted was as a "burden" upon the British war effort as Churchill portrayed the Soviets as in constant need of British support.[124] Churchill argued that the failed expedition to Greece in April–May 1941 had "saved" Moscow later in 1941 as he argued that the campaign in the Balkans had given the Soviet Union an extra five weeks by delaying Operation Barbarossa.[121] Operation Barbarossa was due to start on 21 May 1941, but was instead was launched on 22 June 1941. However, the reason for the delay was not the campaigns in the Balkans, but rather the heavy rains in the spring of 1941 that made the made the mud roads of Eastern Europe almost impassable.[121]

In The Grand Alliance Churchill stated that Japan was in a "sinister twilight" in 1941, although he believed she could be deterred by forceful diplomacy. When the Japanese prime minister Fumimaro Konoe on 28 July 1941 ordered the occupation of southern French Indochina, disregarding Roosevelt's long-standing warnings, Roosevelt imposed sanctions on Japan, most notably the oil embargo. Churchill did not mention that he opposed this, and barely mentioned that Britain followed the United States in imposing an oil embargo on Japan.[125]

Churchill's wish to have the United States enter the war against Germany led him to be dragged into policies against Japan that would have preferred to have avoided. Because he was out of office from 1929 to 1939, Churchill was frank about the essential weakness of the Singapore strategy, namely that Singapore was only a naval base and not the great fortress that it was presented as.[126] Churchill wrote about the decision to activate a mini-version of the Singapore strategy, by sending out Force Z under the command of Admiral Tom Philips to Singapore, that that he believed that Force Z would be sufficient to deter Japan, which he admitted had been a mistake.[127] Admiral Philips-a convinced "battleship admiral" who had a dismissive attitude towards air power-took Force Z into the South China Sea without air cover to confront a Japanese invasion fleet heading towards Malaya (modern Malaysia), which resulted in Force Z being sunk by Japanese aircraft operating out of French Indochina (modern Vietnam).[127] Churchill initially sought to explain Philips's folly as being due to aircraft having never sunk warships before, only to be told by his research assistants that they had indeed done so, which led him to exclude that argument from the final draft.[127] Churchill took a defensive tone in The Grand Alliance about his appointment of Phillips, whom he described as a "trusted" friend, which presumably meant he was aware of Phillips's views about air power to command Force Z led .[127] In fact, Churchill had had a falling-out with Phillips after he had opposed Churchill's plans to send an expedition to Greece, and the decision to appoint Phillips to command Force Z seems to have been as a punishment.[117] Churchill suffered much guilt over the death of Phillips who went down with the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, which was reflected in the chapter of the destruction of Force Z.[128] In the Official History of the Second World War Stephen Roskill later attacked Churchill for sending Force Z to Singapore. Bell writes that much of such criticism is mistaken as Force Z was intended to deter Japan from going to war with in the first place. Bell writes that it is unclear what Churchill wanted to happen, but that privately he blamed Phillips for actively seeking out enemy targets instead of retreating. He did not urge bold action on Phillips the way he had on Cunningham earlier in the year. He wrote to Commodore Allen along these lines in response to Roskill's criticisms in 1953. In his memoirs Churchill had claimed that a meeting, "mostly Admiralty", was convened on the night of 9 December in the Cabinet War Room, and they decided to sleep on it before ordering Phillips to seek refuge with the US Fleet. Roskill could not find any evidence in the Chiefs of Staff and Defence Committee minutes to back this up, and concluded that "they never discussed "the disappearing strategy"" although he was careful to attribute this supposed untruth to Churchill's memoirs rather than to Churchill himself. However, Churchill's claim is confirmed by Alan Brooke's diary, not available when Roskill was writing.[129]

Churchill lashed out at Australian Prime Minister John Curtin in The Grand Alliance for ordering the Australian troops serving in Egypt home to defend against the expected Japanese invasion, and for his famous appeal on 27 December 1941 for the United States to defend Australia from a Japanese invasion, which Churchill regarded as almost treason to the British Empire.[130] Churchill claimed that Curtin should have imposed conscription (a politically toxic move for any government in Canberra) instead of asking for American help.[130] By contrast Churchill praised Peter Fraser for his "loyal" attitude in keeping the New Zealand troops in Egypt.[130]

Volume Four: The Hinge of Fate (covers 1942-3, published 1950)

[edit]Writing

[edit]In July 1949 Pownall, who was writing up the North African campaign, wrote to Churchill that the sections on the Battle of El Alamein were largely finished but still needed checking by the Air Historian Denis Richards (later a biographer of Portal).[131]

In the summer of 1949[132] Churchill had another working holiday on Lake Garda in Italy. He had planned to work on Volume 4 but had to work on the Volume 3 draft in response to criticism from the US publishers.[133] Back at Chartwell by autumn 1949, and recovering from a mild stroke with a General Election looming, Churchill was conducting sporadic work on Volume 4 while still polishing Volume 3.[134]

Sir Norman Brook suggested the title The Hinge of Fate for Volume 4.[135] Early in 1950 Churchill was enjoying another paid holiday in Madeira and had worked on seventeen chapters of Volume 4 with Deakin and Pownall. He returned to Britain when Attlee called the 1950 United Kingdom general election. The very narrow Labour majority made Churchill's publishers keener than ever that he should finish the work. He managed a frenetic fortnight of work over the Easter Parliamentary Recess. The US publishers were not happy as only a quarter of the text was (in their words) "original writing" and there had also been a sharp drop off in sales because of excessive quotes from documents and minute details of military operations. Churchill dictated, but did not send, a sarcastic reply about what a "miracle" he had produced and how well the publishers had done out of it.[136] After a visit to Chartwell Malcolm Muggeridge recorded (23 August) that Churchill had lost interest in his memoirs and was just "stringing together masses of documents" and had let slip to his US publishers that he had not even written "certain chapters" himself.[137]

Churchill had planned to work on Volume 4 at Biarritz in September, but the US publishers insisted it be ready by 11 September so that they could publish for the Christmas market. Churchill had to cancel his writing holiday altogether because the Parliamentary Autumn Recess was postponed because of the outbreak of the Korean War, and a vital manuscript was lost in the transatlantic post, forcing Emery Reves to assemble a staff of twenty for three days around the clock work to make 1,000 changes to a previous draft. The United States Department of State demanded some excisions on security grounds. Extracts began to appear on 10 October, shortly after the Inchon Landings, a coincidence remarked on by the New York Times (which wrote that the UN forces were fighting the "same old fight for freedom and the democratic life that Churchill led").[138]

The following year The Times Literary Supplement (3 August 1951) commented on this volume that "as a chronicler of war, Mr Churchill has, hitherto, been disappointing" but The Hinge of Fate was "a breathtaking book" and that in its pages Churchill was "a romantic, as immortally young as the hero of Treasure Island" but had "massive common sense" and "superhuman resilience".[139]

Analysis

[edit]Churchill was on very friendly terms with the Anglophile Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky, which was acknowledged, but rather downplayed as the Soviet Union was Britain's enemy in the Cold War.[107] The intense dispute between Ernest Bevin and Lord Beaverbrook over control of the wartime economy, which ended with Lord Beaverbrook being dropped from the cabinet in 1942, was mentioned, but downplayed as the Bevin-Beaverbrook dispute did not present the Churchill cabinet in the best light.[140] In domestic politics, Churchill directed most of his fire against Sir Stafford Cripps, a leading figure on the left-wing of the Labour Party, who had angered Churchill during the war by his advocacy of independence for India.[140] Because Clement Attlee was prime minister when the first volumes were being written, Churchill did not mention his disagreements with him over strategic bombing (to which Attlee was opposed) and over plans for a post-war welfare state (to which Churchill was opposed).[141]

During his time as wartime prime minister, Churchill believed that strategic bombing of German cities might be sufficient to win the war, and as such had devoted immense sums of money to RAF Bomber Command.[142] Churchill had been greatly influenced by a 1942 paper by his science adviser Lord Cherwell known as the "dehousing paper".[143] Following the destruction of Coventry by the Luftwaffe on 14–15 November 1940 that left most of the people of Coventry homeless, there had been a fall in productivity in war industries in the Coventry area. Cherwell professed in the "dehousing paper" to have worked out a precise formula based on the experience of Coventry and other British cities if Bomber Command could "dehouse" a sufficient number of German workers by destroying their homes, the resulting decline in productivity would cripple the German economy, and in this way Britain would win the war without fighting any costly battles on land.[144] Lord Cherwell did not mention in his paper that "dehousing" bombing would probably often kill the people living in the destroyed houses.[144] Churchill accepted Lord Cherwell's advice and on 22 February 1942 appointed the single-minded and ruthless Air Marshal Arthur "Bomber" Harris as the new commander of Bomber Command.[144] Churchill played down his support for strategic bombing as many of the wartime claims made by the RAF leaders that strategic bombing alone could defeat Germany proved to be highly erroneous, and instead portrayed strategic bombing more as a supplement to the campaigns on land instead of the war-winning campaign that it was envisioned of at the time.[145] In fact, on 21 July 1942 Churchill told the war cabinet that he believed that it was possible to win the war via strategic bombing alone, a claim he repeated to Stalin during his summit in Moscow on 12 August 1942.[146] During the Moscow summit, Churchill referred to the bombing raid on Cologne on 30 May 1942 that destroyed much of the city, and told Stalin he "hoped to shatter twenty German cities as we had shattered Cologne".[146] During the war, the Deputy Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, was highly sceptical about the claims being made by Harris and the other "bomber barons", leading to Churchill to Attlee a lengthy memo on 29 July 1942 saying that Britain's only hope of winning the war was via strategic bombing.[147] In the same memo, Churchill wrote that both the British Army and the US Army were hopelessly inferior to the Wehrmacht in every respect and that "it will certainly be several years before British and American land forces will be capable of beating the Germans on even terms in the open field".[147] None of Churchill's wartime statements about winning the war via bombing alone were included in The Second World War books, nor his hope that every home in Germany would be destroyed nor his statements that it was not possible to defeat the Wehrmacht in battle, making the strategic bombing only option.[148]

Reynold noted that Churchill supported the "deal with Darlan" in 1942 under which Admiral François Darlan defected to the Allied side, bringing with him Algeria and Morocco, and at the time saw Darlan as a better French ally than Charles de Gaulle, whom Churchill gave the impression that he always suoported.[149] The picture of Darlan varied from volume to volume. In volume 2, Their Finest Hour, Darlan had been depicted as a devious and dishonest leader, a corrupt pro-Nazi schemer whose word was unreliable. This was a justification for the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir in 1940.[150] In The Hinge of Fate, Churchill portrayed Darlan as an honourable but misguided French patriot.[151]

In the first draft, Churchill had planned to be more critical of Operation Jubilee, the Dieppe Raid on 19 August 1942 that failed disastrously, but chose not as the man responsible for the raid, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten was a powerful man related to the Royal family who would have likely sued for libel had the first draft been published.[152] As a result, Churchill simply wrote that the raid had failed with no discussion as to why.[153] Mountbatten wrote to Churchill in 1950 that he objected to the statement that 70% of the men of the 2nd Canadian Division had been "lost" at Dieppe as only 18% of the men of the 2nd Division had been killed (by "losses" Churchill meant all the men killed, wounded or taken prisoner, which would have amounted to 70%).[154] Mountbatten also insisted that Churchill say the Chiefs of Staff had approved the raid, though there was and still is no evidence in support of this claim.[155] On 1 July 1942, Convoy PQ 17 on the highly dangerous "Murmansk run" though the Arctic Ocean to the Soviet city of Archangel had its protection withdrawn by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound, following erroneous reports that the German battleship Tirpitz had set sail from her base in the far north of Norway.[156] Without protection, the merchantmen of PQ 17 were defenceless against the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine, and 24 of the 35 merchantmen were sunk with the survivors dying in the freezing Arctic Ocean.[157] Churchill seemed rather surprised that Pound had given the order to withdrew the escorts from PQ 17, especially when it emerged that it was not entirely clear if the Admiral Tirpitz had actually set sail or not, and kept looking for some evidence that would excuse Pound's decision to withdrew the escorts.[156] Churchill was sensitive about PQ 17 as he been seeking to ease Pound into retirement since early 1942.[158] By early 1942, Pound was visibly suffering from the brain cancer that was to kill him in 1943, and Churchill had noticed that he had much trouble paying attention at meetings.[159] Churchill was normally quite ruthless about sacking generals, admirals and air marshals whom he believed had failed him, but he had a soft spot for Pound, whom he unsuccessfully tried to nudge into retirement.[159] Churchill's defensive tone about PQ 17 was due to the fact that many in the Royal Navy believed that Pound should have been sacked as First Sea Lord in 1942 instead of being allowed to continue to serve, despite his failing health, until September 1943.[160]

Churchill had difficult wartime relations with the Polish government-in-exile and painted a negative and critical picture of their leaders except for General Władysław Sikorski.[161] Churchill had found the demands from the Polish leaders such as Stanisław Mikołajczyk about restoring Poland's pre-war eastern frontiers to be highly unrealistic, causing difficulties in his relations with Joseph Stalin.[162] Churchill believed the Polish claim that the Soviet NKVD had committed the Katyn massacre of 1940 to be correct, but found the timing of the allegation in April 1943, when the Red Army was doing the bulk of the fighting against the Wehrmacht, to be highly inconvenient.[163] When writing the chapter on the Katyn Forest massacre, Deakin told Churchill that the Soviet claim that the Germans had executed 14,000 Polish POWs in 1941 was "incredible", a statement that Churchill changed to requiring "act of faith".[163] Against the charge that he not done enough to champion the Polish case, Churchill merely stated in The Hinge of Fate that it was impossible to determine in 1943 who had committed the Katyn Forest massacre.[164] Churchill got along well with President Edvard Beneš of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, and his picture of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile was as positive as his picture of the Polish government-in-exile was negative.[162]

During the war, Churchill was incensed by the advice from President Franklin D. Roosevelt that he should grant independence to India, which he portrayed in this volume as American meddling in the affairs of the British Empire, or "idealism at other people's expense".[165] In a blunt passage, Churchill wrote that Roosevelt's comparison of the Indian struggle for independence with the American Revolutionary War was wrong because the Thirteen Colonies deserved independence while India did not.[166] Such criticism was rare as Roosevelt was a beloved figure in the United States, and Churchill did not want to damage the Anglo-American "Special Relationship".[165] Churchill genuinely liked Roosevelt as a man and his books he tended to portray Roosevelt as an excellent president misled by his "bad" advisers such as General George Marshall and Admiral Ernest J. King whose views on grand strategy Churchill did not share.[167] Churchill did not mention that many British leaders had a low opinion of the American military with for example King George VI writing to Churchill in February 1943 after the American defeat in the Battle of Kasserine Pass that the British would "have to do all the fighting" as he felt the Americans were useless in combat.[168] Churchill printed the King's letter in The Hinge of Fate, but excluded his criticism of the US Army which had angered American readers.[168] Churchill praised the combat record of the Indian Army as a validation of the Raj as he wrote that India had played a major role in the British war effort.[166] But at the same time Churchill denounced all the peoples and politicians of India as ungrateful for the Raj.[166] Churchill portrayed the British as having sacrificed and suffered so much for the Indians who never expressed any thanks and kept unreasonably demanding independence.[166] In the first draft, Churchill accused Mahatma Gandhi of being a Hindu fundamentalist who wanted to oppress Muslims and as a pro-Nazi traitor who would have been all too willing to serve as a puppet Maharaja for the Japanese.[166] This passage was removed from the final draft after Churchill was told by Sir Norman Brook that it was false, inflammatory and likely to cause problems in Anglo-Indian relations.[166] The attack on Gandhi was removed, but throughout all of 'The Second World War, Churchill made clear his dislike of Gandhi and the Indian independence movement.[166]

Churchill wrote favourably about the South African prime minister General Jan Smuts, the Dominion prime minister whom Churchill most liked and respected.[169] Smuts was portrayed as the wise and benevolent old Boer general, the embodiment of an Afrikaner takhaar (patriarch), who was always giving sound advice. An additional reason for the favourable treatment was Smuts' support for Churchill's preference for operations in the Mediterranean at the expense of operations in France.[170] Of the British Army generals in the war, the one who Churchill liked and respected the most was Field Marshal Harold Alexander, whom Churchill credited with more or less single-handedly stopping the Japanese from following up their conquest of Burma in the spring of 1942 with an invasion of India.[171] Field Marshal Alan Brooke, who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) for most of the war, is barely mentioned in the books and even the few mentions that made of him relate to his command of II Corps in France in 1940, not as CIGS.[172]

Reflecting his traditional conception of naval war, Churchill devoted entire chapters to the pursuit of the Admiral Graf Spee in 1939 and the sinking of the Bismarck in 1941, but gave less attention to the campaign against the far more dangerous U-boats.[173] In 1938, British farms provided only enough food to feed 30% of the British people with the rest imported on board merchantmen from all over the world, making the United Kingdom very vulnerable to a U-boat induced famine. The sea battles usually fought at night between the "wolf packs" of the U-boats against the Royal Navy destroyers that protected the convoys of merchantmen and tankers were crucial for the survival of much of the British population, but Churchill did not seem to find the subject very interesting.[174] Churchill wrote (Volume 2 p529) that "the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-Boat peril". Bell writes that in fact his interest was "sporadic rather than constant". Initially in 1940 he thought Britain had sufficient merchant ships and prioritised sending tanks and other war supplies to the Middle East, only to be forced to take an interest in the U-Boat war in the period from December 1940 to June 1941 (a period corresponding, with a time lag, to the so-called First Happy Time of the U-Boats).[175] In the chapter of his memoirs "The U-boat Paradise" Churchill took a great interest in the "Second Happy Time" between January and July 1942 when the U-boats wreaked havoc upon shipping off the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts of the United States; this came across as an exercise in score-settling.[176] Admiral Ernest J. King, the Anglophobic commander of the U.S. Navy, refused to adopt the convoy system under the grounds that it was a British invention and likewise refused to have the lights turned off in American cities, thereby making silhouetted ships at sea perfect targets for the U-boats at night. In the chapter "The U-boat Paradise", Churchill grimly noted that the American shipping paid the price in first half of 1942 as the Americans refused to learn from British experience.[176] Bell writes that Churchill actually had a period of complacency because of the entry of the US Navy into the war, followed by another period of concern between November 1942 and May 1943. Stephen Roskill later (in the official History of the Second World War and more openly in his Churchill and the Admirals (1977)) criticised Churchill for prolonging the Battle of the Atlantic by instead deploying bombers to strategic bombing of German cities, which was then only of limited effectiveness.[177] Bell writes that there is some truth in this, but that Churchill also went along, against his better judgement, with air activity in the Bay of Biscay from June 1942 to the end of February 1943. This bombing sank seven U-Boats, less than one per month, whereas North East Atlantic air patrols sank seventeen U-boats for only a third of the flying time. Bell also comments that it was Churchill's Anti-U-boat Warfare Committee which arranged for modified Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers to be deployed from late 1942, finally helping to win the Battle of the Atlantic.[178] However, Bidwell and Graham comment that in his speeches and writings Churchill did much to popularise the idea that there had been a "Battle of the Atlantic" divided into phases. In so doing he both "satisfied dyed in-the-wool Mahanists who spurn[ed] the guerre de course (Mahan had stressed the importance of sea superiority and blockade)" and entertained the public who wanted to read about exciting battles. In fact, they argue, the main focus of the British and Royal Canadian Navies was "safe arrival" of convoys. It was only in 1943, when the "Battle" was largely won through naval and air superiority and the US Navy, which did not have to prioritise carrying supplies for Britain, took a more offensive attitude, that sinking U-Boats became an end in itself.[179]