Winston Churchill's "Wilderness" years, 1929–1939

Winston Churchill retained his UK Parliamentary seat at the 1929 general election as member for Epping, but the Conservative Party was defeated and, with Ramsay MacDonald forming his second Labour government, Churchill was out of office and would remain so until the beginning of the Second World War in September 1939. This period of his life has been dubbed his "wilderness years",[1] but he was extremely active politically as the main opponent of the government's policy of appeasement in the face of increasing German, Italian and Japanese militarism.

Marlborough and the India Question: 1929–1932

[edit]

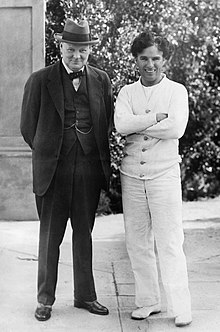

In the 1929 general election, Churchill retained his Epping seat but the Conservatives were defeated and MacDonald formed his second Labour government.[2] Out of office, Churchill began work on Marlborough: His Life and Times, a four-volume biography of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough.[3] Hoping that the Labour government could be ousted, he gained Baldwin's approval to work towards establishing a Conservative-Liberal coalition, although many Liberals were reticent.[3] In August he travelled to Canada with his brother and son, giving speeches in Ottawa and Toronto, before travelling through the United States.[4] In San Francisco he met with William Randolph Hearst, who convinced Churchill to write for his newspapers;[5] in Hollywood he dined with the film star Charlie Chaplin.[6] From there he travelled through the Mojave Desert to the Grand Canyon and then to Chicago and finally New York City.[6]

Back in London, Churchill was angered by the Labour government's decision—backed by the Conservative Shadow Cabinet—to grant Dominion status to India.[7] He argued that giving India enhanced levels of home rule would hasten calls for full independence from the British Empire.[8] In December 1930 he was the main speaker at the first public meeting of the Indian Empire Society, set up to oppose the granting of Dominion status.[9] In his view, India was not ready for home rule. He believed that the Hindu Brahmin caste would gain control and further oppress both the "untouchables" and the religious minorities.[10] When riots between Hindus and Muslims broke out in Cawnpore in March 1931, he cited it in support of his argument.[11]

Churchill called for swift action against any Indian independence activists engaged in illegal activity.[9] He wanted the Indian National Congress party to be disbanded and its leaders deported.[12] In 1930, he stated that "Gandhi-ism and everything it stands for will have to be grappled with and crushed".[13] He thought it "alarming and nauseating" that the Viceroy of India agreed to meet with independence activist Mohandas Gandhi, whom Churchill considered "a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir".[14] These views enraged Labour and Liberal opinion although were supported by many grassroot Conservatives.[15] Angered that Baldwin was supporting the reform, Churchill resigned from the Shadow Cabinet.[16]

In October 1930, Churchill published his autobiography, My Early Life, which sold well and was translated into multiple languages.[17] The October 1931 general election was a landslide victory for the Conservatives[18] Churchill nearly doubled his majority in Epping, but he was not given a ministerial position.[19] The following month saw the publication of The Eastern Front, the final volume of The World Crisis.[20] The Commons debated Dominion Status for India on 3 December and Churchill insisted on dividing the House. This backfired as only 43 MPs supported him and 369 voted for the government.[20] According to a history of the British Secret Service, "Churchill's constitutional position in relation to the intelligence community in his wilderness years was wholly remarkable. Unable to tolerate the lack of intelligence after he left office in 1929, Churchill sought it from [Desmond] Morton and no doubt from others. Early in the life of the first National Government, Morton consulted Ramsay MacDonald. 'Tell him whatever he wants to know, keep him informed,' the prime minister replied. He put that permission in writing and it was endorsed by his successors, Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain. Astonishingly, Churchill was then supplied on the instructions of three prime ministers with secret intelligence which he was to use as the basis of public attacks on their defence policies and of his own campaign for rearmament."[21]

At this time, however, Churchill's main interest was in recovering financial losses—about £12,000 (equivalent to about £958,280 in 2023)—he had sustained in the Wall Street Crash and he embarked on a potentially lucrative lecture tour of North America, accompanied by Clementine and Diana. They arrived in New York City on 11 December and Churchill gave his first lecture in Worcester, Massachusetts the following night.[18][20] On 13 December, he was back in New York and travelled by cab to meet his friend Bernard Baruch. Having left the cab, he was crossing Fifth Avenue when he was knocked down by a car that was exceeding the speed limit. He suffered a head wound, two cracked ribs and general bruising from which he developed neuritis. He was hospitalised for eight days and then began a period of convalescence at his hotel until New Year's Eve.[22] While he was there he sent an article about his experience to the Daily Mail and afterwards received thousands of letters and telegrams from well-wishers.[23] To further his convalescence, he and Clementine took ship to Nassau for three weeks but Churchill became depressed there, not just about the accident but also about his financial and political losses.[24] Meanwhile, the lecture agency managed to reschedule many of his engagements and, on returning to America in late January, he was able to fulfil nineteen of them until 11 March, though he remained mostly in the north-east and did not go further west than Chicago.[25] He arrived back home on 18 March.[24]

Having worked on Marlborough for much of 1932, Churchill in late August decided to visit the battlefields of "John Duke" (Churchill's pet name for him) in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. He travelled with Lindemann.[26] In Munich, he met Ernst Hanfstaengl, a friend of Hitler, who was then rising in prominence. Talking to Hanfstaengl, Churchill raised concerns about Hitler's anti-Semitism and, probably because of that, missed the opportunity to meet his future enemy.[27] Churchill went from Munich to Blenheim. Soon afterwards, he was afflicted with paratyphoid fever. He was taken over the border into Austria and spent two weeks at a sanatorium in Salzburg.[28] He returned to Chartwell on 25 September, still working on Marlborough. Two days later, he collapsed while walking in the grounds after a recurrence of paratyphoid which caused an ulcer to haemorrhage. He was taken to a London nursing home and remained there until late October, missing the Conservative Party Conference.[29]

While Churchill was in Salzburg, the German Chancellor Franz von Papen requested that the other Western powers accept Germany's right to re-arm, something they had been forbidden from doing by the Treaty of Versailles. Foreign Secretary John Simon, rejected the request and affirmed that Germany was still bound by the treaty's disarmament clauses. Churchill later supported Simon as he believed that a re-armed Germany would soon pursue the re-conquest of territories lost in the previous conflict.[30]

Warnings about Germany and the abdication crisis: 1933–1936

[edit]After Hitler came to power on 30 January 1933, Churchill was quick to recognise the menace to civilisation of such a regime. As early as 13 April that year, he addressed the Commons on the matter, speaking of "odious conditions in Germany" and the threat of "another persecution and pogrom of Jews" being extended to other countries, including Poland.[31][32] On the issue of militarism, Churchill expressed alarm that the British government had reduced air force spending and warned that Germany would soon overtake Britain in air force production.[33][34]

Between October 1933 and September 1938, the four volumes of Churchill's Marlborough: His Life and Times were published.[35] In November 1934, he gave a radio broadcast in which he warned of Nazi intentions and called on Britain to prepare itself for conflict. This was the first time that his concerns about German militarism were heard by such a large audience.[36] In December, the India Bill entered parliament and was passed in February 1935. Churchill and 83 other Conservative MPs voted against it.[37] He continued to express misgivings but did message Gandhi, saying: "You have got the thing now; make it a success and if you do I will advocate your getting much more".[38] In June 1935, MacDonald resigned and was replaced as prime minister by Baldwin.[39] Baldwin then led the Conservatives to victory in the 1935 general election; Churchill retained his seat with an increased majority but was again left out of the government.[40]

Armed with official data provided clandestinely by two senior civil servants, Desmond Morton and Ralph Wigram, Churchill was able to speak with authority about what was happening in Germany, especially the development of the Luftwaffe.[41] He was involved with the Anti-Nazi Council, despite its being primarily leftist in political outlook, and called for improved training of troops and airmen. He also warned that industry must prepare for wartime production.[42]

In January 1936, Edward VIII succeeded his father, George V, as monarch. Churchill liked Edward but disapproved of his desire to marry an American divorcee, Wallis Simpson.[43] Marrying Simpson would necessitate Edward's abdication and a constitutional crisis developed.[44] Churchill was opposed to abdication and, in the House of Commons, he and Baldwin clashed on the issue.[45] Afterwards, although Churchill immediately pledged loyalty to George VI, he wrote that the abdication was "premature and probably quite unnecessary".[46]

Anti-appeasement: 1937–1939

[edit]

In May 1937, Baldwin resigned and was succeeded as prime minister by Neville Chamberlain. At first, Churchill welcomed Chamberlain's appointment but, in February 1938, matters came to a head after Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden resigned over Chamberlain's appeasement of Mussolini,[47] a policy which Chamberlain was extending towards Hitler.[48]

Meanwhile, Churchill had continued writing fortnightly articles for the Evening Standard, and these were reprinted in various newspapers across Europe through the efforts of Emery Reves' Paris-based press service.[49] In September 1937, Churchill wrote an Evening Standard piece in which he directly appealed to Hitler, asking the latter to cease his persecution of Jews and religious organisations.[50] The following month, a selection of his articles were published in a collected volume called Great Contemporaries.[51]

In 1938, Churchill warned the government against appeasement and called for collective action to deter German aggression. In March, the Evening Standard ceased publication of his fortnightly articles, but the Daily Telegraph published them instead.[52][53] Following the German annexation of Austria, Churchill spoke in the House of Commons, declaring that "the gravity of the events[…] cannot be exaggerated".[54] He began calling for a mutual defence pact among European states threatened by German expansionism, arguing that this was the only way to halt Hitler.[55] This was to no avail as, in September, Germany mobilised to invade the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia.[56] Churchill visited Chamberlain at Downing Street and urged him to tell Germany that Britain would declare war if the Germans invaded Czechoslovak territory; Chamberlain was not willing to do this.[57] On 30 September, Chamberlain signed up to the Munich Agreement, agreeing to allow German annexation of the Sudetenland. Speaking in the House of Commons on 5 October, Churchill called the agreement "a total and unmitigated defeat".[58][59][60]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 464.

- ^ Rhodes James 1970, p. 183; Gilbert 1991, p. 489.

- ^ a b Gilbert 1991, p. 491.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 492–493.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 493–494.

- ^ a b Gilbert 1991, p. 494.

- ^ Rhodes James 1970, pp. 195–196; Gilbert 1991, p. 495.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 495.

- ^ a b Gilbert 1991, p. 497.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 495, 497, 500–501.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 501.

- ^ Rhodes James 1970, p. 198.

- ^ Rhodes James 1970, p. 198; Gilbert 1991, p. 498.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 499–500.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 500.

- ^ Rhodes James 1970, p. 199; Gilbert 1991, p. 499.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 496.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2001, p. 443.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 502–503.

- ^ a b c Gilbert 1991, p. 503.

- ^ Andrew, Christopher M. (1986). Her Majesty's Secret Service : the making of the British intelligence community (1st American ed.). New York, N.Y., U.S.A.: Viking. p. 355. ISBN 0-670-80941-1. OCLC 12889018.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 443–444.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 504.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2001, p. 444.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 504–505.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 445.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 508.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 508–509.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 509–511.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 468–470.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 516.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 470.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 513–515, 530–531.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 522, 533, 563, 594.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 533.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 538–539.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 540.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 544.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 547.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 479–480.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 554–564.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 568.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 568–569.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 569.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 570.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 514–515.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 576–577.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 576.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 580.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 580–581.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 516.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 588.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 589.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, pp. 590–591.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 594.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 595.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 598.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 527.

- ^ "Churchill's Wartime Speeches – A Total and Unmitigated Defeat". The Churchill Society, London. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gilbert, Martin (1991). Churchill: A Life. London: Heinemann. ISBN 978-04-34291-83-0.

- Jenkins, Roy (2001). Churchill. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-03-30488-05-1.

- Manchester, William The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill; Alone: 1932–1940 (Little, Brown, 1988).

- Rhodes James, Robert (1970). Churchill: A Study in Failure 1900–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-02-97820-15-4.

- Roberts, Andrew Churchill: Walking with Destiny. (London: Allen Lane, 2018), a major scholarly biography.