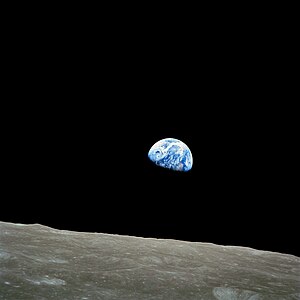

Earthrise

Earthrise is a photograph of Earth and part of the Moon's surface that was taken from lunar orbit by astronaut William Anders on December 24, 1968, during the Apollo 8 mission.[1][2][3] Nature photographer Galen Rowell described it as "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken".[4]

Anders' color image had been preceded by a crude black-and-white 1966 raster image taken by the Lunar Orbiter 1 robotic probe, the first American spacecraft to orbit the Moon.

Details

[edit]

Earthrise was taken by astronaut William Anders during the Apollo 8 mission, the first crewed voyage to orbit the Moon.[4][5] One account suggests that before Anders found a suitable 70 mm color film, mission commander Frank Borman took a black-and-white photograph of the scene, with the Earth's terminator touching the horizon. In fact, all three photographs had been taken by Anders.[6] The land mass position and cloud patterns in this image are the same as those of the color photograph entitled Earthrise.[7]

The photograph was taken from lunar orbit on December 24, 1968, 16:39:39.3 UTC,[8][9] with a highly modified Hasselblad 500 EL with an electric drive. The camera had a simple sighting ring, rather than the standard reflex viewfinder, and was loaded with a 70 mm film magazine containing custom Ektachrome film developed by Kodak. Immediately prior, Anders had been photographing the lunar surface with a 250 mm lens; the lens was subsequently used for the Earthrise images.[6]

Anders: Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! There's the Earth coming up. Wow, that's pretty.

Borman: Hey, don't take that, it's not scheduled. (joking)[1]

Anders: (laughs) You got a color film, Jim?

Hand me that roll of color quick, would you...

Lovell: Oh man, that's great!

There were many images taken at that point. The mission audio tape establishes several photographs were taken, on Borman's orders, with the enthusiastic concurrence of Jim Lovell and Anders. Anders took the first color shot, then Lovell who notes the setting (1/250th of a second at f/11), followed by Anders with another very similar shot (AS08-14-2384).

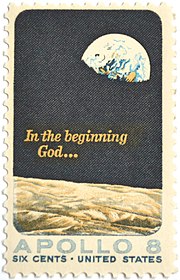

A black and white reproduction of Borman's image appeared in his 1988 autobiography, captioned, "One of the most famous pictures in photographic history – taken after I grabbed the camera away from Bill Anders". Borman noted that this was the image "the Postal Service used on a stamp, and few photographs have been more frequently reproduced".[10]: 212 The photograph reproduced is not the same image as the Anders photograph; aside from the orientation, the cloud patterns differ. Borman later recanted this story and agreed that the black and white shot was also taken by Anders, based on evidence presented by transcript and a video produced by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio employee, Ernie Wright.[6][8]

After Apollo 8's return, NASA technicians – not able to wait for normal film processing – drove four hours from Houston to Corpus Christi, Texas to the family-owned R&R Photo Studio & Color Labs (later known as R&R PhotoTechnics) which at that time was the first and only place in South Texas with color photo processing equipment. More importantly, R&R featured the rare four-hour Ektachrome slide processing capability for the professional 220-size film used by the astronauts' Hasselblad, making R&R a convenient same-day trip for NASA's critical need.[citation needed]

There, the owner Raul Rodriguez took the film, which had traveled 500,000 miles (800,000 km) to the far side of the Moon and back. He personally developed the slides and copied them to regular 220 negatives, which he then also had to develop. Then he exposed and printed the requested photos in quick 8" x 10" glossy size, one of which would eventually be known as Earthrise. Rodriguez then returned the slides, negatives and photos to the appreciative NASA technicians to rush back to Houston.[citation needed]

For the Earthrise slides, then later the Earthrise negatives, Rodriguez used a German-made Merz S2A dual-rocking-drum developer. To print the first Earthrise photo, he used an Auto-focus Chromega D4 enlarger that had modern dial-in color filters. It sat on a motorized-drive, lightproof, 11" wide, roll-paper carrier. The images were fully defined via Rodriguez's then-state-of-the-art, self-replenishing, Mylar-leader, continuous-feed roll-photo paper processor produced by the Nord photo company then based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.[citation needed]

The stamp issue reproduces the cloud, color, and crater patterns of the Anders picture. Anders is described by Borman as holding "a masters degree in nuclear engineering"; Anders was thus tasked as "the scientific crew member ... also performing the photography duties that would be so important to the Apollo crew who actually landed on the Moon".[10]: 193

On the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 8 mission in 2018, Anders stated: "It really undercut my religious beliefs. The idea that things rotate around the pope and up there is a big supercomputer wondering whether Billy was a good boy yesterday? It doesn't make any sense. I became a big buddy of [atheist scientist] Richard Dawkins."[11]

Geometry

[edit]

The original image was rotated 95 degrees clockwise to produce the published Earthrise orientation to better convey the sense of the Earth rising over the moonscape. The published photograph shows Earth rotated clockwise approximately 135° from the typical north–south-Pole-oriented perspective, with south to the left.[13]

Legacy

[edit]Earthrise was used as the cover photograph for the Spring 1969 issue of the Whole Earth Catalog.[14]

In Life's 2003 book 100 Photographs that Changed the World, wilderness photographer Galen Rowell called Earthrise "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken".[15][16] Another author called its appearance the beginning of the environmental movement.[17] Fifty years to the day after taking the photo, William Anders observed, "We set out to explore the moon and instead discovered the Earth."[18]

In October 2018, two of the craters seen in the photo were named Anders' Earthrise and 8 Homeward by the Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN) of the International Astronomical Union. The craters had previously been designated only with letters.[19]

Joni Mitchell sings on her 1976 song "Refuge of the Roads": "In a highway service station / Over the month of June / Was a photograph of the Earth / Taken coming back from the Moon / And you couldn't see a city / On that marbled bowling ball / Or a forest or a highway / Or me here least of all …"

Stamp

[edit]

In 1969, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp (Scott# 1371) commemorating the Apollo 8 flight around the Moon. The stamp featured a detail (in color) of the Earthrise photograph, and the words, "In the beginning God...", recalling the Apollo 8 Genesis reading.[20]

2013 simulation

[edit]In 2013, in commemoration of the 45th anniversary of the Apollo 8 mission, NASA issued a video about the taking of the photograph.[21] This computer-generated visualization used data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft, which had provided detailed images of the lunar surface that could be matched with those taken every 20 seconds by an automatic camera on Apollo 8. The resulting video, re-creating what the astronauts would have seen (rotated 90 degrees clockwise to match the perspective presented in the photograph), was synchronized with the recording of the crew's conversation as they became the first humans to witness an Earthrise. The video reconstruction team was led by Ernie Wright, and included explanatory narration written and read by Andrew Chaikin.[8][22] Chaikin writes that all the photographs of the rising Earth on Apollo 8's fourth orbit were taken by Anders.[23]

Potential earthrises as seen from the Moon's surface

[edit]The Earth "rose" because the spacecraft was traveling over the Moon's surface. An earthrise that might be witnessed from the surface of the Moon would be quite unlike moonrises on Earth. Because the Moon is tidally locked with the Earth, one side of the Moon always faces toward Earth. Interpretation of this fact would lead one to believe that the Earth's position is fixed on the lunar sky and no earthrises can occur; however, the Moon librates slightly, which causes the Earth to draw a Lissajous figure on the sky. This figure fits inside a rectangle 15°48' wide and 13°20' high (in angular dimensions), while the angular diameter of the Earth as seen from the Moon is only about 2°. This means that earthrises are visible near the edge of the Earth-observable surface of the Moon (about 20% of the surface). Since a full libration cycle takes about 27 days, earthrises are very slow, and it takes about 48 hours for Earth to clear its diameter.[24] During the course of the month-long lunar orbit, an observer would additionally witness a succession of "Earth phases", much like the lunar phases seen from Earth. That is what accounts for the half-illuminated globe, the ashen glow, seen in the photograph.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Chasing the Moon: Transcript, Part Two". American Experience. PBS. July 10, 2019. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (December 21, 2018). "Apollo 8's Earthrise: The Shot Seen Round the World – Half a century ago today, a photograph from the moon helped humans rediscover Earth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ Boulton, Matthew Myer; Heithaus, Joseph (December 24, 2018). "We Are All Riders on the Same Planet – Seen from space 50 years ago, Earth appeared as a gift to preserve and cherish. What happened?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Rowell, Galen. "The Earthrise Photograph". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (December 14, 2005). "Earthrise". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

- ^ a b c Chaikin, Andrew (January–February 2018). "Who Took the Legendary Earthrise Photo From Apollo 8?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Poole, Robert (2008). Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth. New Haven, Connecticut, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13766-8.

- ^ a b c Wright, Ernie; Kaplan, Eytan (October 15, 2018). "SVS: Earthrise: The 45th Anniversary". NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio. Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ The mission transcript (day 4, p. 114) shows the shot taken at 03 03 49 (mission time 3d3h49), and the launch was on 1968-12-21 12:51 UTC. However, the 2013 reconstruction by Ernie Wright mentioned below as well as in the previous reference yielded a mission time of 3d3h48m39.3s, meaning 16:39:39.3 UTC.

- ^ a b Borman, Frank (1988). Countdown: An Autobiography. New York, NY, US: Morrow (Silver Arrow Books). ISBN 0-688-07929-6.

- ^ Earthrise: how the iconic image changed the world Archived June 8, 2024, at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 2018-12-24.

- ^ "Earthrise – Apollo 8". NASA on The Commons. NASA. December 24, 1968. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020 – via Flickr.

- ^ "See the Apollo 8 mission and learn more from the astronaut who lived it". The Seattle Times. December 7, 2012. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Brand, Stewart [@stewartbrand] (April 22, 2020). "The Spring 1969 WHOLE EARTH CATALOG had the "Earthrise" photo on the cover" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Rowel, Galen. "100 Photographs that Changed the World by Life". The Digital Journalist. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ Widmer, Ted (December 24, 2018). "What Did Plato Think the Earth Looked Like? – For millenniums, humans have tried to imagine the world in space. Fifty years ago, we finally saw it". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (July 14, 2009). "On Hand for Space History, as Superpowers Spar". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ Anders, Bill (December 24, 2018). "50 Years After 'Earthrise,' a Christmas Eve Message from Its Photographer". Space.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ Schulz, Rita. "Lunar craters named in honor of Apollo 8". EurekAlert!. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "Apollo 8 Issue – Postal Bulletin: March 27, 1969". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ NASA. "45th anniversary of the Earthrise Photo". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Steigerwald, Bill (December 20, 2013). "NASA Releases New Earthrise Simulation Video". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on June 14, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ Chaikin, Andrew. "Who Took the Legendary Earthrise Photo From Apollo 8?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Makowiecki, Piotr (1985). Pomyśl zanim odpowiesz (in Polish). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo "Wiedza Powszechna". ISBN 83-214-0419-7.

External links

[edit]- Earthrise: The 45th Anniversary (NASA Goddard, YouTube channel)

- Earthrise: The 45th Anniversary Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine – NASA Goddard webpage with various reconstruction videos

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, reconstruction video of the Earthrise photograph