Zine

A zine (/ziːn/ ⓘ ZEEN; short for magazine or fanzine) is a small-circulation self-published work of original or appropriated texts and images, usually reproduced via a copy machine. Zines are the product of either a single person or of a very small group, and are popularly photocopied into physical prints for circulation. A fanzine (blend of fan and magazine) is a non-professional and non-official publication produced by enthusiasts of a particular cultural phenomenon (such as a literary or musical genre) for the pleasure of others who share their interest. The term was coined in an October 1940 science fiction fanzine by Russ Chauvenet and popularized within science fiction fandom, entering the Oxford English Dictionary in 1949.

Popularly defined within a circulation of 1,000 or fewer copies; in practice, however, many zines are produced in editions of fewer than 100. Among the various intentions for creation and publication are developing one's identity, sharing a niche skill or art, or developing a story, as opposed to seeking profit. Zines have served as a significant medium of communication in various subcultures, and frequently draw inspiration from a "do-it-yourself" philosophy that disregards the traditional conventions of professional design and publishing houses, proposing an alternative, confident, and self-aware contribution.[1] Handwritten zines, or carbon zines, are individually made, emphasizing a personal connection between creator and reader,[1] turning imagined communities into embodied ones.[2]

Historically, zines have provided community for socially isolated individuals or groups through the ability to express and pursue common ideas and subjects. For this reason, zines have cultural and academic value as tangible traces of marginal communities, many of which are otherwise little-documented. Zines present groups that have been dismissed with an opportunity to voice their opinion, both with other members of their own communities or with a larger audience. This has been reflected in the creation of zine archives and related programming in such mainstream institutions as the Tate museum and the British Library.[3]

Written in a variety of formats from desktop-published text to comics, collages and stories, zines cover broad topics including fanfiction, politics, poetry, art & design, ephemera, personal journals, social theory, intersectional feminism, single-topic obsession, or sexual content far enough outside the mainstream to be prohibitive of inclusion in more traditional media. (An example of the latter is Boyd McDonald's Straight to Hell, which reached a circulation of 20,000.[4]) Although there are a few eras associated with zine-making, this "wave" narrative proposes a limited view of the vast range of topics, styles and environments zines occupied.

History

[edit]Overview and origins

[edit]Dissidents, under-represented, and marginalized groups have published their own opinions in leaflet and pamphlet form for as long as such technology has been available. The concept of zines can be traced to the amateur press movement of the late 19th and early 20th century, which would in turn intersect with Black literary magazines during the Harlem Renaissance, and the subculture of science fiction fandom in the 1930s. The popular graphic-style associated with zines is influenced artistically and politically by the subcultures of Dada, Fluxus, Surrealism, and Situationism.[1]

Many[citation needed] trace zines' lineage from as far back as Thomas Paine's exceptionally popular 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, Benjamin Franklin's literary magazine for psychiatric patients at a Pennsylvania hospital and The Dial (1840–44) by Margaret Fuller and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[5][1]

Zines were given a pop culture revival in March 2021 with the release of the Amy Poehler-directed film Moxie, released by Netflix, about a 16-year old high school student who starts a feminist zine to empower the young women at her school.[6]

1920s

[edit]"Little magazines" during the Harlem Renaissance

[edit]In the 1920s during the Harlem Renaissance, a group of Black creatives in Harlem began a literary magazine "the better to express ourselves freely and independently – without interference from old heads, white or [black]."[7] This led to the creation of a "little magazine" entitled Fire!!. Only one issue of Fire!! was released, but this inspired the creation of other "little magazines" by Black authors. Contributions by Black writers, artists, and activists to the zine movement are often overlooked, in part "because they had such short runs and were spearheaded by a single or small group of individuals."[8]

1930s–1960s and science fiction

[edit]

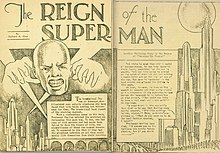

During and after the Great Depression, editors of "pulp" science fiction magazines became increasingly frustrated with letters detailing the impossibilities of their science fiction stories. Over time they began to publish these overly-scrutinizing letters, complete with their return addresses. Hugo Gernsback published the first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories in 1926. In January 1927, Gernsback introduced a large letter column which printed reader's addresses. allowing them to write to each other; it was out of this mailing list that fans' own science fiction fanzines began.[9] Fans also began writing to each other not only about science fiction but about fandom itself, leading to perzines.[10] Science fiction fanzines vary in content, from short stories to convention reports to fanfiction were one of the earliest incarnations of the zine and influenced subsequent publications.[11] "Zinesters" like Lisa Ben and Jim Kepner honed their talents in the science fiction fandom before tackling gay rights, creating zines such as "Vice Versa" and "ONE" that drew networking and distribution ideas from their science fiction roots.[12] A number of leading science fiction and fantasy authors rose through the ranks of fandom, creating "pro-zines" such as Frederik Pohl and Isaac Asimov. The first science fiction fanzine, The Comet, was published in 1930 by the Science Correspondence Club in Chicago and edited by Raymond A. Palmer and Walter Dennis.[13] The first version of Superman (a bald-headed villain) appeared in the third issue of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's 1933 fanzine Science Fiction.[14]

Star Trek

[edit]The first media fanzine was a Star Trek fan publication called Spockanalia, published in September 1967[15][16] by members of the Lunarians.[17] Some of the earliest examples of academic fandom were written on Star Trek zines, specifically K/S (Kirk/Spock) slash zines, which featured a gay relationship between the two. Author Joanna Russ wrote in her 1985 analysis of K/S zines that slash fandom at the time consisted of around 500 core fans and was 100% female.[18]

"K/S not only speaks to my condition. It is written in Female. I don't mean that literally, of course. What I mean is that I can read it without translating it from the consensual, public world, which is sexist, and unconcerned with women per se, and managing to make it make sense to me and my condition."[19]

Russ observed that while science fiction fans looked down on Star Trek fans, Star Trek fans looked down on K/S writers.[19] Kirk/Spock zines contained fanfiction, artwork, and poetry created by fans. Zines were then sent to fans on a mailing list or sold at conventions. Many had high production values and some were sold at convention auctions for hundreds of dollars.[18]

Janus and Aurora

[edit]Janus, later called Aurora, was a science fiction feminist zine created by Janice Bogstad and Jeanne Gomoll in 1975. It contained short stories, essays, and film reviews. Among its contributors were authors such as Octavia Butler, Joanna Russ, Samuel R. Delany, and Suzette Hayden Elgin. Janus/Aurora was nominated for the Hugo Award for "Best Fanzine" in 1978, 1979, and 1980. Janus/Aurora was the most prominent science fiction feminist zine during its run, as well as one of the only zines that dealt with such content.[20]

Comics

[edit]Comics were mentioned and discussed as early as the late 1930s in the fanzines of science fiction fandom. They often included fan artwork based on existing characters as well as discussion of the history of comics. Through the 1960s, and 1970s, comic fanzines followed general formats, such as the industry news and information magazine (The Comic Reader was one example), interview, history and review-based fanzines, and the fanzines which basically represented independent comic book-format exercises.[citation needed]

In 1936, David Kyle published The Fantasy World , possibly the first comics fanzine.[21][22]

Malcolm Willits and Jim Bradley started The Comic Collector's News in October 1947.[23] In 1953, Bhob Stewart published The EC Fan Bulletin,[22] which launched EC fandom of imitative Entertaining Comic fanzines. Among the wave of EC fanzines that followed, the best-known was Ron Parker's Hoo-Hah! In 1960, Richard and Pat Lupoff launched their science fiction and comics fanzine Xero and in 1961, Jerry Bails' Alter Ego, devoted to costumed heroes, became a focal point for superhero comics fandom.[22]

Horror

[edit]Calvin T. Beck's Journal of Frankenstein (later Castle of Frankenstein) and Gary Svehla's Gore Creatures were the first horror fanzines created as more serious alternatives to the popular Forrest J Ackerman 1958 magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland.[citation needed] Garden Ghouls Gazette – a 1960s horror title under the editorship of Dave Keil, then Gary Collins—was later headed by Frederick S. Clarke and in 1967 became the respected journal Cinefantastique. It later became a prozine under journalist-screenwriter Mark A. Altman and has continued as a webzine.[24] Richard Klemensen's Little Shoppe of Horrors,[25] having a particular focus on "Hammer Horrors", began in 1972 and is still publishing as of 2017.[26] The Baltimore-based Black Oracle (1969–1978) from writer-turned-John Waters repertory member George Stover was a diminutive zine that evolved into the larger-format Cinemacabre. Stover's Black Oracle partner Bill George published his own short-lived zine The Late Show (1974–1976; with co-editor Martin Falck), and later became editor of the Cinefantastique prozine spinoff Femme Fatales.[citation needed][27] In the mid-1970s, North Carolina teenager Sam Irvin published the horror/science-fiction fanzine Bizarre which included his original interviews with UK actors and filmmakers; Irvin would later become a producer-director in his own right.[28] Japanese Fantasy Film Journal (JFFJ) (1968–1983) from Greg Shoemaker covered Toho's Godzilla and his Asian brethren. Japanese Giants (JG) appeared in 1974 and was published for 30 years.[29] In 1993, G-FAN was published, and reached its 100th regularly published issue in Fall 2012.[30] FXRH (Special effects by Ray Harryhausen) (1971–1976) was a specialized zine co-created by future Hollywood FX artist Ernest D. Farino.[citation needed]

Board games

[edit]Board game-focused zines, especially those focused on the board game Diplomacy, took off in the 1960s. These not only contained news and articles about the hobby, but also served as a common form for the organisation of play-by-mail games.[31][32]

Rock and roll

[edit]Several fans active in science fiction and comics fandom recognized a shared interest in rock music, and the rock fanzine was born. Paul Williams and Greg Shaw were two such science fiction fans turned rock zine editors. Williams' Crawdaddy! (1966) and Shaw's two California-based zines, Mojo Navigator Rock and Roll News (1966) and Who Put the Bomp (1970), are among the most popular early rock fanzines.

Crawdaddy! (1966) quickly moved from its fanzine roots to become one of the first rock music "prozines" with paid advertisers and newsstand distribution.[33] Bomp remained a fanzine, featuring many writers who would later become prominent music journalists, including Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus, Ken Barnes, Ed Ward, Dave Marsh, Mike Saunders and R. Meltzer as well as cover art by Jay Kinney and Bill Rotsler (both veterans of science fiction and Comics fandom). Other rock fanzines of this period include denim delinquent (1971) edited by Jymn Parrett, Flash (1972) edited by Mark Shipper, Eurock Magazine (1973–1993) edited by Archie Patterson and Bam Balam written and published by Brian Hogg in East Lothian, Scotland (1974).

In the 1980s, with the rise of stadium superstars, many home-grown rock fanzines emerged. At the peak of Bruce Springsteen's megastardom following the Born in the U.S.A. album and Born in the U.S.A. Tour in the mid-1980s, there were no less than five Springsteen fanzines circulating at the same time in the UK alone, and many others elsewhere.[citation needed] Gary Desmond's Candy's Room, coming from Liverpool, was the first in 1980. This was quickly followed by Dan French's Point Blank, Dave Percival's The Fever, Jeff Matthews' Rendezvous, and Paul Limbrick's Jackson Cage.[citation needed] In the US, Backstreets Magazine started in Seattle in 1980 and still continues today as a glossy publication, now in communication with Springsteen's management and official website.[citation needed] Crème Brûlée documented post-rock genre and experimental music (1990s).[citation needed]

1970s and punk

[edit]Punk zines emerged as part of the punk subculture in the late 1970s, along with the increasing accessibility to copy machines, publishing software, and home printing technologies.[34] Punk became a genre for the working class because of the economic necessity to use creative DIY methods, which were echoed in both zine and Punk music creation. Zines became vital to the popularization and spread of punk spreading to countries outside the UK and America, such as Ireland, Indonesia, and more by 1977.[35][36] Amateur, fan-created zines played an important role in spreading information about different scenes (city or regional-based subcultures) and bands (e.g. British fanzines like Mark Perry's Sniffin Glue and Shane MacGowan's Bondage) in the pre-Internet era. They typically included reviews of shows and records, interviews with bands, letters, and ads for records and labels.

The punk subculture in the United Kingdom spearheaded a surge of interest in fanzines as a countercultural alternative to established print media.[citation needed] The first and still best known UK 'punk zine' was Sniffin' Glue, produced by Deptford punk fan Mark Perry which ran for 12 photocopied issues; the first issue produced by Perry immediately following (and in response to) the London debut of the Ramones on 4 July 1976.[citation needed] Other UK fanzines included Blam!, Bombsite, Burnt Offering, Chainsaw, New Crimes, Vague, Jamming, Artcore Fanzine, Love and Molotov Cocktails, To Hell With Poverty, New Youth, Peroxide, ENZK, Juniper beri-beri, No Cure,Communication Blur, Rox, Grim Humour, Spuno, Cool Notes and Fumes.

By 1990, Maximum Rocknroll "had become the de facto bible of the scene, presenting a "passionate yet dogmatic view" of what hardcore was supposed to be."[37] HeartattaCk and Profane Existence took the DIY lifestyle to a religious level for emo and post-hardcore and crust punk culture. Slug and Lettuce started at the state college of PA and became an international 10,000 copy production – all for free.[38] In Canada, the zine Standard Issue chronicles the Ottawa hardcore scene. The Bay Area zine Cometbus was first created at Berkeley by the zinester and musician Aaron Cometbus. Gearhead Nation was a monthly punk freesheet that lasted from the early 1990s to 1997 in Dublin, Ireland.[39] Some hardcore punk zines became available online such as the e-zine chronicling the Australian hardcore scene, RestAssured. In Italy, Mazquerade ran from 1979 to 1981 and Raw Art Fanzine ran from 1995 to 2000.[40][41]

In the US, Flipside (created by Al Kowalewski, Pooch (Patrick DiPuccio), Larry Lash (Steven Shoemaker), Tory, X-8 (Sam Diaz)) and Slash (created by Steve Samioff and Claude Bessy) were important punk zines for the Los Angeles scene, both debuting in 1977.[42] In 1977 in Australia, Bruce Milne and Clinton Walker fused their respective punk zines Plastered Press and Suicide Alley to launch Pulp; Milne later went on to invent the cassette zine with Fast Forward, in 1980.[43][44] In the American Midwest, a zine called Touch and Go described the area's hardcore scene from 1979 to 1983. We Got Power described the LA scene from 1981 to 1984, and included show reviews and band interviews with groups including DOA, the Misfits, Black Flag, Suicidal Tendencies, and the Circle Jerks. My Rules was a photo zine that included photos of hardcore shows from across the US an in Effect, launched in 1988 described the New York City punk scene. Among later titles, Maximum RocknRoll is a major punk zine, with over 300 issues published. As a result, in part, of the popular and commercial resurgence of punk in the late 1980s, and after, with the growing popularity of such bands as Sonic Youth, Nirvana, Fugazi, Bikini Kill, Green Day and the Offspring, a number of other punk zines have appeared, such as Dagger, Profane Existence, Punk Planet, Razorcake, Slug and Lettuce, Sobriquet and Tail Spins. The early American punk zine Search and Destroy eventually became the influential fringe-cultural magazine Re/Search.

"In the post-punk era several well-written fanzines emerged that cast an almost academic look at earlier, neglected musical forms, including Mike Stax' Ugly Things, Billy Miller and Miriam Linna's Kicks, Jake Austen's Roctober, Kim Cooper's Scram, P. Edwin Letcher's Garage & Beat, and the UK's Shindig! and Italy's Misty Lane."[citation needed] Mark Wilkins, the promotion director for 1982 onwards US punk/thrash label Mystic Records, had over 450 US fanzines and 150 foreign fanzines he promoted to regularly. He and Mystic Records owner Doug Moody edited The Mystic News Newsletter which was published quarterly and went into every promo package to fanzines. Wilkins also published the highly successful Los Angeles punk humor zine Wild Times and when he ran out of funding for the zine syndicated some of the humorous material to over 100 US fanzines under the name of Mystic Mark.[citation needed]

Factsheet Five

[edit]During the 1980s and onwards, Factsheet Five (the name came from a short story by John Brunner), originally published by Mike Gunderloy and now defunct, catalogued and reviewed any zine or small press creation sent to it, along with their mailing addresses. In doing so, it formed a networking point for zine creators and readers (often the same people). The concept of zine as an art form distinct from fanzine, and of the "zinesters" as member of their own subculture, had emerged. Zines of this era ranged from perzines of all varieties to those that covered an assortment of different and obscure topics. Genres reviewed by Factsheet Five included quirky, medley, fringe, music, punk, grrrlz, personal, science fiction, food, humour, spirituality, politics, queer, arts & letters, comix.[1]

1990s and riot grrrl

[edit]The riot grrrl movement emerged from the DIY Punk subculture in tandem with the American era of third-wave feminism, and used the consciousness-raising method of organizing and communication.[45][46][47] As feminist documents, they follow a longer legacy of feminist and women's self-publication that includes scrapbooking, periodicals and health publications, allowing women to circulate ideas that would not otherwise be published.[45] The American publication Bikini Kill (1990) introduced the Riot Grrrl Manifesto in their second issue as a way of establishing space.[1] Zinesters Erika Reinstein and May Summer founded the Riot Grrrl Press to serve as a zine distribution network that would allow riot grrrls to "express themselves and reach large audiences without having to rely on the mainstream press".[48]

"BECAUSE we girls want to create mediums that speak to US. We are tired of boy band after boy band, boy zine after boy zine, boy punk after boy punk after boy . . . BECAUSE in every form of media I see us/myself slapped, decapitated, laughed at, trivialized, pushed, ignored, stereotyped, kicked, scorned, molested, silenced, invalidated, knifed, shot, choked, and killed ... BECAUSE every time we pick up a pen, or an instrument, or get anything done, we are creating the revolution. We ARE the revolution."

Women use this grassroots medium to discuss their personal lived experiences, and themes including body image, sexuality, gender norms, and violence to express anger, and reclaim/refigure femininity.[45][49][50][51] Scholar and zinester Mimi Thi Nguyen notes that these norms unequally burdened riot grrrls of color with allowing white riot grrrls access to their personal experiences, an act which in itself was supposed to address systemic racism.[52]

BUST - "The voice of the new world order" was created by Debbie Stoller, Laurie Hanzel and Marcelle Karp in 1993 to propose an alternate to the popular mainstream magazines Cosmopolitan and Glamour.[1] Additional zines following this path are Shocking Pink (1981–82, 1987–92), Jigsaw (1988– ), Not Your Bitch 1989–1992 (Gypsy X, ed.) Bikini Kill (1990), Girl Germs (1990), Bamboo Girl (1995– ), BITCH Magazine (1996– ), Hip Mama (1997– ), Kitten Scratches (1999) and ROCKRGRL (1995–2005).

In the mid-1990s, zines were also published on the Internet as e-zines.[53] Websites such as Gurl.com and ChickClick were created out of dissatisfaction of media available to women and parodied content found in mainstream teen and women's magazines.[54][55] Both Gurl.com and ChickClick had a message board and free web hosting services, where users could also create and contribute their own content, which in turn created a reciprocal relationship where women could also be seen as creators rather than consumers.[53][56]: 154

Commercialization

[edit]Starting in this decade[which?], multinational companies started appropriating and commodifying zines and DIY culture.[1] Their faux zines created a commercialized hipster lifestyle. By late in the decade, independent zinesters were accused of "selling out" to make a profit.[1]

Distribution and circulation

[edit]Zines are sold, traded or given as gifts at symposiums, publishing fairs, record and book stores and concerts, via independent media outlets, zine 'distros', mail order or through direct correspondence with the author. They are also sold online on distro websites, Etsy shops, blogs, or social networking profiles and are available for download. While zines are generally self-published, there are a few independent publishers who specialize in art zines such as Nieves Books in Zurich, founded by Benjamin Sommerhalder, and Café Royal Books founded by Craig Atkinson in 2005. In recent years a number of photocopied zines have risen to prominence or professional status and have found wide bookstore and online distribution. Notable among these are Giant Robot, Dazed & Confused, Bust, Bitch, Cometbus, Doris, Brainscan, The Miscreant, and Maximum RocknRoll.[citation needed]

Live map of zine distributors worldwide

There are many catalogued and online based mail-order distros for zines. The longest running distribution operation is Microcosm Publishing in Portland, Oregon. Some other longstanding operations include Great Worm Express Distribution in Toronto, CornDog Publishing in Ipswich in the UK, Café Royal Books in Southport in the UK, AK Press in Oakland, California,[57] Missing Link Records in Melbourne.[58] and Wasted Ink Zine Distro in Phoenix, AZ.[59]

Libraries and archives

[edit]A number of major public and academic libraries as well as museums carry zines and other small press publications, often with a specific focus (e.g. women's studies) or those that are relevant to a local region.

Libraries and institutions with notable zine collections include:

- Barnard College Library[60]

- The University of Iowa Special Collections[61][62]

- The Sallie Bingham Center for Women's History and Culture at Duke University[63]

- The Tate Museum[64]

- The British Library[65][66]

- Harvard University's Schlesinger Library[67]

- Los Angeles Public Library[68]

- San Francisco Public Library[69]

- Jacksonville Public Library[70]

- Interference Archive[71]

- Anchor Archive Zine Library[72]

- Toronto Zine Library[73]

- Denver Zine Library[74]

The Indie Photobook Library, an independent archive in the Washington, D.C., area, is a large collection of photo books and photo zines dating from 2008 to 2016 which the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University acquired in 2016.[75][76] In California, the Long Beach Public Library was the first public library in the state to start circulating zines for three weeks at a time in 2015. In 2017, the Los Angeles Public Library started to circulate zines publicly to its patrons as well. Both projects have been credited to librarian Ziba Zehdar, who has been an advocate in promoting public circulation of zines at libraries in California.[77][78][79]

It has been suggested that the adoption of zine culture by powerful and prestigious institutions contradicts the function of zines as declarations of agency by marginalized groups.[3]

Zine fests, workshops, and clubs

[edit]

There has been a resurgence in the alternative publication culture beginning in the 2010s, in tandem with the influx of zine libraries and as a result of the digital age, which has sparked zine festivals across the globe. The San Francisco Zine Fest started in 2001 and features up to 200+ exhibitors, while the Los Angeles Zine Fest started in 2012 with only a handful of exhibitors, now hosting over 200 exhibitors. These are considered to be some of the biggest zine fests in the United States,[80]

Other big zine fests across the globe include, San Francisco Zine Fest, Brooklyn Zine Fest, Chicago Zine Fest, Feminist Zine Fest, Amsterdam Zine Jam, and Sticky Zine Fair. At each zine fest, the zinester can be their own independent distributor and publisher simply by standing behind a table to sell or barter their work. Over time, zinesters have added posters, stickers, buttons and patches to these events. In many libraries, schools and community centers around the world, zinesters hold meetings to create, share, and pass down the art of making zines.

2000s and the effect of the Internet

[edit]With the rise of the Internet in the mid-1990s, zines initially faded from public awareness; this is possibly due to the ability of private web-pages to fulfill much the same role of personal expression. Indeed, many zines were transformed into Webzines, such as Boing Boing or monochrom. The metadata standard for cataloging zines is xZineCorex, which maps to Dublin Core.[81] E-zine creators were originally referred to as "adopters" because of their use of pre-made type and layouts, making the process less ambiguous.[1] Since, social media, blogging and vlogging have adopted a similar do-it-yourself publication model.

In the UK Fracture and Reason To Believe were significant fanzines in the early 2000s, both ending in late 2003. Rancid News filled the gap left by these two zines for a short while. On its tenth issue Rancid News changed its name to Last Hours with 7 issues published under this title before going on hiatus. Last Hours still operates as a webzine though with more focus on the anti-authoritarian movement than its original title. Artcore Fanzine (established in 1986) continues to this day, recently publishing a number of 30-year anniversary issues.[82]

Mira Bellwether's zine Fucking Trans Women, published in 2010 online and 2013 in print, proved influential in the field of transgender sexuality, receiving both scholarly[83][84] and popular-culture attention.[85][86] It was described in Sexuality & Culture as "a comprehensive guide to trans women's sexuality"[84]: 965 and The Mary Sue as "the gold standard in transfeminine sex and masturbation".[86]

In the early 2000s, zines with comics in them had a "thriving" fandom.[87]

Television shows

[edit]Two popular kids shows in the late 1990s and early 2000s featured zine-making: Our Hero (2000–02) and Rocket Power (1999–2004).[1] The main character in Our Hero, Kale Stiglic, writes about her life in the Toronto suburbs. The episodes are narrated and presented in the form of zine issues that she creates, inheriting her father's storytelling passion. The show won titles from the Canadian Comedy Awards and Gemini Awards during its development.[88]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Triggs, Teal (2010). Fanzines The DIY Revolution. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-7692-6.

- ^ Piepmeier, Alison (2008). "Why Zines Matter: Materiality and the Creation of Embodied Community". American Periodicals: A Journal of History, Criticism, and Bibliography. 18 (2): 213–238. doi:10.1353/amp.0.0004. S2CID 145377264.

- ^ a b Fife, Kirsty (2019). "Not for you? Ethical implications of archiving zines". Punk & Post Punk. 8 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1386/punk.8.2.227_1. S2CID 199233569 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ William E. Jones, True Homosexual Experiences: Boyd McDonald and "Straight to Hell", Los Angeles: We Heard You Like Books, 2016, ISBN 9780996421812, p. 6.

- ^ Piepmeier, Alison (2009). Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. NYU Press. p. 215 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ehrlich, Brenna (8 March 2021). "How Amy Poehler's 'Moxie' Is Bringing Riot Grrrl -- and Bikini Kill -- to a New Generation". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Abby Ann Arthur; Johnson, Ronald M. (1974). "Forgotten Pages: Black Literary Magazines in the 1920s". Journal of American Studies. 8 (3): 363–382. doi:10.1017/S0021875800015930. ISSN 0021-8758. JSTOR 27553130.

- ^ Jensen, Kelly (6 February 2019). "Get To Know The Little Magazines of The Harlem Renaissance". BOOK RIOT. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Iamandi, Petru (2007). "The SF Fandom: A Subculture with a Difference". Proceedings of the Culture, Subculture, Counterculture Conference. Galaţi: 9.

- ^ "zine info". all thumbs press. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Bingham Center Zine Collections | A Brief History of Zines". Duke University Libraries. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "How gay rights got its start in science fiction". Southern California Public Radio. 4 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Moskowitz, Sanders, Sam, Joe (1994). The Origins of Science Fiction Fandom: A Reconstruction. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 17–34.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster - "Reign of the Superman" -- Science Fiction Fanzine V1#3 And Others (1933)". c. 2006. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022.

- ^ Verba, Joan Marie (2003). Boldly Writing: A Trekker Fan & Zine History, 1967–1987 (PDF). Minnetonka MN: FTL Publications. ISBN 978-0-9653575-4-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Grimes, William (21 September 2008). "Joan Winston, 'Trek' Superfan, Dies at 77". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Bacon-Smith, Camille (2000). Science Fiction Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-8122-1530-4.

- ^ a b Grossberg, Lawrence; Nelson, Cary; Treichler, Paula (1 February 2013). Cultural Studies. Routledge. ISBN 9781135201265.

- ^ a b "Concerning K/S." Joanna Russ Papers, Series II: Literary Works: Box 13, Folder #, Page 25. University of Oregon Special Collections.

- ^ "Janus & Aurora |". Sf3.org. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Kyle, David. "Phamous Phantasy Phan". Mimosa no. 24, pp. 25–28.

- ^ a b c The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture, p. 175, at Google Books

- ^ Everyday Information: The Evolution of Information Seeking in America, p. 286, at Google Books

- ^ "Cinefantastique: The Website with a Sense of Wonder". cinefantastiqueonline.com.

- ^ "Little Shoppe of Horrors". littleshoppeofhorrors.com.

- ^ "Little Shoppe of Horrors". www.littleshoppeofhorrors.com.

- ^ "Women in Horror: A Look Back at Femme Fatales Magazine". 21 February 2017.

- ^ "School of Cinematic Arts Directory Profile – USC School of Cinematic Arts". usc.edu.

- ^ "Japanese Giants". www.fum.wiki.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "GFAN Magazine Index". g-fan.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Sharp, Richard (1978). The Game of Diplomacy. A. Barker. ISBN 978-0213166762.

- ^ Tamlyn, Pete (Spring 1985). "Adapting Games for Postal Play". Flagship. No. 6. p. 33.

- ^ Saffle, Michael (2010). "Self-Publishing and Musicology: Historical Perspectives, Problems, and Possibilities". Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association. 66 (4): 731. doi:10.1353/not.0.0376. ISSN 1534-150X.

- ^ Mattern, Shannon (2011). "Click/Scan/Bold: The New Materiality of Architectural Discourse and Its Counter-Publics". Design and Culture. 3 (3): 329–353. doi:10.2752/175470811X13071166525298. S2CID 191353038.

- ^ "Early Irish fanzines". Loserdomzine.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "Collections | IISG". iisg.amsterdam.

- ^ Heller, Jason. "With zines, the '90s punk scene had a living history". archive.today. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Slug and Lettuce". Slug and Lettuce.

- ^ "Gearhead Nation". Zine Wiki. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Perugiamusica.com". perugiamusica.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Raw Art Fanzine: restauro digitale e disponibilità dei numeri degli anni '90". truemetal.it. 26 May 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Hannon, Sharon M. (2010). Punks: A Guide to an American Subculture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36456-3.

- ^ "Fast Forward: A Pre-Internet Story". messandnoise.com. 18 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Fanzines (1970s)". Clinton Walker. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Piepmeier, Alison (2009). Girl Zines: making media, doing feminism. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814767528. OCLC 326484782.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ "Third-wave feminism" (PDF). Rachelyon1.files.wordpress.com. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Dunn, Kevin; Farnsworth, May Summer (2012). ""We Are The Revolution": Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-publishing". Women's Studies. 41 (136–137): 142, 147, 150. doi:10.1080/00497878.2012.636334. S2CID 144211678.

- ^ Sinor, Jennifer (2003). "Another Form of Crying: Girl Zines as Life Writing". Prose Studies: History, Theory, Criticism. 26 (1–2): 246. doi:10.1080/0144035032000235909. S2CID 161495522.

- ^ Stone-Mediatore, Shari (2016). Storytelling/Narrative. Oxford Handbooks Online.

- ^ Licona, Adela (2012). Zines in third space: radical cooperation and borderlands rhetoric. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1438443720.

- ^ Nguyen, Mimi Thi (12 December 2012). "Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival". Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory. 22 (2–3): 173–196. doi:10.1080/0740770X.2012.721082. S2CID 144676874.

- ^ a b Oren, Tasha; Press, Andrea (29 May 2019). The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Feminism. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 9781138845114.

- ^ Copage, Eric V. (9 May 1999). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: NEW YORK ON LINE; Girls Just Want To ..." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Macantangay, Shar (18 April 2000). "Chicks click their way through the Internet". Iowa State Daily. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Shade, Leslie Regan (19 July 2004). "Gender and the Commodification of Community". Community in the Digital Age: Philosophy and Practice. By Feenberg, Andrew. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 151–160. ISBN 9780742529595.

- ^ "Welcome to AK Press". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Missing Link Digital". Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Phoenix zine community continues to grow thanks to ASU alumna". The Arizona State Press. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "Barnard Zine Library". zines.barnard.edu. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Zine and Amateur Press Collections at the University of Iowa". Iowa University Libraries. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Hevelin Collection". UI Libraries Blogs. 11 April 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Wooten, Kelly. "Zines at the Sallie Bingham Center". LibGuides at Duke University. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Show and Tell: Zine collection Launch". Tate Britain. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Do it yourself". The British Library. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Cox, Debbie (2018). "Developing and raising awareness of the zine collections at the British Library". Art Libraries Journal. 43 (2): 77–81. doi:10.1017/alj.2018.5. ISSN 0307-4722.

- ^ Wilson, Anne Marie (8 June 2012). "Finding Zines in the Archives, and Archives in the Zines". Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Zine Library". Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Little Maga/Zine Collection". San Francisco Public Library. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Zine Collection". Jacksonville Public Library. 13 February 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Search Results for 'zines'". Interference Archive. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Home". Anchor Archive Zine Library. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "About". Toronto Zine Library. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "Home". Denver Zine Library. Retrieved 14 January 2025.

- ^ "Indie Photobook Library". Indiephotobooklibrary.org. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Morand, Michael (16 November 2016). "iPL collection adds to Beinecke's strengths in photobooks and modern trends in self-publishing". YaleNews. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "LAPL Zine Library". Tumblr. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Long Beach Public Zine Library". Long Beach Zine Fest. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Check out the zine collection at the Long Beach Public Library". Southern California Public Radio. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "LA Zine Fest Exhibitors". Archived from the original on 17 April 2018.

- ^ Miller, Milo. "xZineCorex: An Introduction" (PDF). Milo Miller. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "Artcore Fanzine | Est. 1986". Artcore Fanzine | Est. 1986. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Bauer, Greta R.; Hammond, Rebecca (April 2015). "Toward a Broader Conceptualization of Trans Women's Sexual Health". Commentary. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 24 (1). Sex Information and Education Council of Canada / University of Toronto Press: 1–11. doi:10.3138/cjhs.24.1-CO1. S2CID 144236595.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Shoshana; Tilley, P. J. Matt; Morgan, Julia (September 2019). "'I Couldn't Imagine My Life Without It': Australian Trans Women's Experiences of Sexuality, Intimacy, and Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy". Sexuality & Culture. 23 (3). Springer Science+Business Media: 962–977. doi:10.1007/s12119-019-09601-x. S2CID 255519091.

- ^ Tourjée, Diana (12 October 2017). "A Guide to Muffing: The Hidden Way to Finger Trans Women". Best You've Ever Had. Broadly. Vice Media. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ a b Valens, Ana (12 July 2022). "This Viral Sex Ed Tip For Trans Women Reveals How We're So Far Behind In Transfeminine Pleasure". The Mary Sue. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "comic book". Encyclopedia Britannica. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "IMDb Our Hero Awards". IMDb.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderberg, Kirsten. Alternative Economies, Underground Communities: A First Hand Account of Barter Fairs, Food Co-ops, Community Clinics, Social Protests and Underground Cultures in the Pacific Northwest & CA 1978–2012. US: 2012.

- Anderberg, Kirsten. Zine Culture: Brilliance Under the Radar. Seattle, US: 2005.

- Bartel, Julie. From A to Zine: Building a Winning Zine Collection in Your Library. American Library Association, 2004.

- Biel, Joe $100 & a T-shirt: A Documentary About Zines in the Northwest. Microcosm Publishing, 2004, 2005, 2008 (Video)

- Biel, Joe Make a Zine: Start Your Own Underground Publishing Revolution (20th anniversary 3rd edn) Microcosm Publishing, 1997, 2008, 2017 ISBN 978-1-62106-733-7

- Block, Francesca Lia and Hillary Carlip. Zine Scene: The Do It Yourself Guide to Zines. Girl Press, 1998.

- Brent, Bill. Make a Zine!. Black Books, 1997 (1st edn.), ISBN 0-9637401-4-8. Microcosm Publishing, with Biel, Joe, 2008 (2nd edn.), ISBN 978-1-934620-06-9.

- Brown, Tim W. Walking Man, A Novel. Bronx River Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9789847-0-0.

- Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm Publishing, 1997, 2008, 2017. ISBN 978-1-62106-484-8.

- Kennedy, Pagan. Zine: How I Spent Six Years of My Life in the Underground and Finally...Found Myself...I Think (1995) ISBN 0-312-13628-5.

- Klanten, Robert, Adeline Mollard, Matthias Hübner, and Sonja Commentz, eds. Behind the Zines: Self-Publishing Culture. Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag, 2011.

- Piepmeier, Alison . Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. NYU Press. (2009) ISBN 978-0-8147-6752-8.

- Spencer, Amy. DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture. Marion Boyars Publishers, Ltd., 2005.

- Watson, Esther and Todd, Mark. "Watcha Mean, What's a Zine?" Graphia, 2006. ISBN 978-0-618-56315-9.

- Vale, V. Zines! Volume 1 (RE/Search, 1996) ISBN 0-9650469-0-7.

- Vale, V. Zines! Volume 2 (RE/Search, 1996) ISBN 0-9650469-2-3.

- Wrekk, Alex. Stolen Sharpie Revolution. Portland: Microcosm Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-9726967-2-5.

- Richard Hugo House Zine Archives and Publishing Project (ZAPP). "ZAPP Seattle". Seattle, US.

- "The Ragged Edge Collection," Skateboarding, Music, and Art Zines from the '1980s and'1990s. Internet Archive