Pirate Party

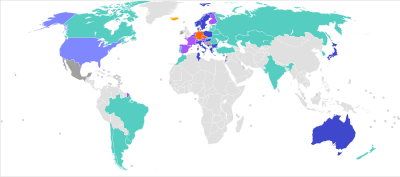

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: Map of elected pirates is heavily outdated. (October 2021) |

Pirate Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ideology | Pirate politics |

| Part of a series on |

| Pirate Parties |

|---|

|

Pirate Party is a label adopted by various political parties worldwide that share a set of values and policies focused on civil rights in the digital age.[1][2][3][4] The fundamental principles of Pirate Parties include freedom of information, freedom of the press, freedom of expression, digital rights and internet freedom. The first Pirate Party was founded in Sweden in 2006 by Rick Falkvinge initially named "Piratpartiet", and the movement has since expanded to over 60 countries.

Central to their vision is the defense of free access to and sharing of knowledge, and opposition to intellectual monopolies. They therefore advocate for copyright and patent laws reform, aiming to make them more flexible and fairer, foster innovation and balance creator' rights with public access to knowledge. Specifically, they support shorter copyright terms and promote open access to scientific research, educational resources, and courses.

Pirate parties are strong proponents of free and open-source software development. They recognize its inherent benefits: it provides freedom of use, modification and distribution, transparency to avoid unfair practices, global collaboration, innovation and cost reduction, and enhanced security through code verifiability. Net neutrality represents another key pillar: they advocate for equal access to the internet and oppose any attempts to restrict or prioritize internet traffic. They promote universal internet access, digital inclusion, and STEM and cybersecurity education to address digital divide. Equally crucial in their programs are public and private investments in R&D, tech startups, digital infrastructure, smart city technologies to optimize urban infrastructures, and robust cybersecurity measures to protect these systems from cyberattacks. Some Pirate parties also support universal basic income as a response to the economic challenges posed by advanced automation.

They think platform economy can be more equitable and more inclusive if it is based also on commons-based peer production and collaborative consumption, viewing technological innovations as part of the global digital commons—freely accessible to everyone. In contrast to many traditional political positions, Pirate parties reject cyber sovereignty and digital protectionism, advocating instead for the free flow of information across borders and the reduction of digital barriers between countries, while also reducing the influence of both corporate and state monopolies. Therefore, they argue that the internet should remain an open public space, free from restrictions, where people can access, create, and share content without fear of coercion. In terms of governance, Pirate Parties support the implementation of open e-government to enhance transparency, reduce costs, and increase the efficiency of decision-making processes. They propose a hybrid democratic model that integrates direct digital democracy (e-democracy) mechanisms with representative democratic institutions. This decentralised and participatory governance, known as collaborative e-democracy, aims to distribute participation and decision-making among citizens through digital tools, allowing them to directly influence public policies (e-participation). It also incorporates forms of AI-assisted governance, secure and transparent electronic voting systems, data-driven decision-making processes, evidence-based policies, technology assessments, and anti-corruption measures to strengthen democratic processes and prevent manipulation and fraud.

Furthermore, these parties strongly defend open-source, decentralized and privacy-enhancing technologies such as blockchain, cryptocurrencies, peer-to-peer networks, messaging apps with end-to-end encryption, virtual private networks, private and anonymous browsers ecc. considering them essential tools to protect personal data, individual privacy and information security, both online and offline, against mass surveillance, data collection without consent, content censorship without due process, forced decryption, internet throttling or blocking, backdoor requirements in encryption, discriminatory algorithmic practices, unauthorized access to personal data, and the abuse of power by Big Tech.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Ultimately, protecting individual freedom is at the core of their political agenda, seen as a bulwark against the growing power of corporations and governments in controlling information and digital autonomy. This aligns perfectly with cyber-libertarian values and principles.[11]

While the name pirate party originally alluded to online piracy, members have made concerted efforts to connect pirate parties to all forms of piracy, from pirate radio to the Golden Age of Pirates. Pirate parties are often considered outside of the economic left–right spectrum or to have context-dependent appeal.[12]

History

[edit]The first Pirate Party to be established was the Pirate Party of Sweden (Swedish: Piratpartiet), whose website was launched on 1 January 2006 by Rick Falkvinge. Falkvinge was inspired to found the party after he found that Swedish politicians were generally unresponsive to Sweden's debate over changes to copyright law in 2005.[13]

The United States Pirate Party was founded on 6 June 2006 by University of Georgia graduate student Brent Allison. The party's concerns were abolishing the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, reducing the length of copyrights from 95 years after publication or 70 years after the author's death to 14 years, and the expiry of patents that do not result in significant progress after four years, as opposed to 20 years. However, Allison stepped down as leader three days after founding the party.[14]

The Pirate Party of Austria (German: Piratenpartei Österreichs) was founded in July 2006 in the run-up to the 2006 Austrian legislative election by Florian Hufsky and Jürgen "Juxi" Leitner.[15]

The Pirate Party of Finland was founded in 2008 and entered the official registry of Finnish political parties in 2009.

The Pirate Party of the Czech Republic (Czech: Česká pirátská strana) was founded on 19 April 2009 by Jiří Kadeřávek.

The 2009 European Parliament election took place between the 4 and 7 June 2009, and various Pirate Parties stood candidates. The most success was had in Sweden, where the Pirate Party of Sweden won 7.1% of the vote, and had Christian Engström elected as the first ever Pirate Party Member of European Parliament (MEP).[16][17] Following the introduction of the Treaty of Lisbon, the Pirate Party of Sweden were afforded another MEP in 2011, that being Amelia Andersdotter.

On 30 July 2009, the Pirate Party UK was registered with the Electoral Commission. Its first party leader was Andrew Robinson, and its treasurer was Eric Priezkalns.[18][19][20]

In April 2010, an international organisation to encourage cooperation and unity between Pirate Parties, Pirate Parties International, was founded in Belgium.[21]

In the 2011 Berlin state election to the Abgeordnetenhaus of Berlin, the Pirate Party of Berlin (a state chapter of Pirate Party Germany) won 8.9% of the vote, which corresponded to winning 15 seats.[22][23] John Naughton, writing for The Guardian, argued that the Pirate Party of Berlin's success could not be replicated by the Pirate Party UK, as the UK does not use a proportional representation electoral system.[24]

In the 2013 Icelandic parliamentary election, the Icelandic Pirate Party won 5.1% of the vote, returning three Pirate Party Members of Parliament. Those were Birgitta Jónsdóttir for the Southwest Constituency, Helgi Hrafn Gunnarsson for Reykjavik Constituency North and Jón Þór Ólafsson for Reykjavik Constituency South.[25][26] Birgitta had previously been an MP for the Citizens' Movement (from 2009 to 2013), representing Reykjavik Constituency South. As of 2015[update], it was the largest political party in Iceland, with 23.9% of the vote.[27]

The 2014 European Parliament election took place between 22 and 24 May. Felix Reda was at the top of the list for Pirate Party Germany, and was subsequently elected as the party received 1.5% of the vote. Other notable results include the Czech Pirate Party, who received 4.8% of the vote, meaning they were only 0.2% shy of getting elected, the Pirate Party of Luxembourg, who received 4.2% of the vote, and the Pirate Party of Sweden, who received 2.2% of the vote, but lost both their MEPs.[28]

Reda had previously worked as an assistant in the office of former Pirate Party MEP Amelia Andersdotter.[29] On 11 June 2014, Reda was elected vice-president of the Greens/EFA group in the European Parliament.[30] Reda was given the job of copyright reform rapporteur.[31]

The Icelandic Pirate Party was leading the national polls in March 2015, with 23.9%. The Independence Party polled 23.4%, only 0.5% behind the Pirate Party. According to the poll, the Pirate Party would win 16 seats in the Althing.[32][33] In April 2016, in the wake of the Panama Papers scandal, polls showed the Icelandic Pirate Party at 43% and the Independence Party at 21.6%,[34] although the Pirate Party eventually won 15% of the vote and 10 seats in the 29 October 2016 parliamentary election.

In April 2017, a group of students at University of California, Berkeley formed a Pirate Party to participate in the Associated Students of the University of California senate elections, winning the only third-party seat.[35]

The Czech Pirate Party entered the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Parliament for the first time after the election held on 20 and 21 October 2017, with 10.8% of the vote.

The Czech Pirate Party, after finishing in second place with 17.1% of the vote in the 2018 Prague municipal election held on 5 and 6 October 2018, formed a coalition with Prague Together and United Forces for Prague (TOP 09, Mayors and Independents, KDU-ČSL, Liberal-Environmental Party and SNK European Democrats). The representative of the Czech Pirate Party, Zdeněk Hřib, was selected to be Mayor of Prague. This was probably the first time a pirate party member became the mayor of a major world city.

At the 2019 European Parliament election, three Czech Pirate MEPs and one German Pirate MEP were voted in and joined the Greens–European Free Alliance, the aforementioned group in the European Parliament that had previously included Swedish Pirate MEPs and German Julia Reda.

Copyright and censorship

[edit]Some campaigns have included demands for the reform of copyright and patent laws.[36] In 2010, Swedish MEP Christian Engström called for supporters of amendments to the Data Retention Directive to withdraw their signatures, citing a misleading campaign.[37]

International organizations

[edit]

Pirate Parties International

[edit]Pirate Parties International (PPI) is the umbrella organization of the national Pirate Parties. Since 2006, the organization has existed as a loose union[38] of the national parties. Since October 2009, Pirate Parties International has had the status of a non-governmental organization (Feitelijke vereniging) based in Belgium. The organization was officially founded at a conference from 16 to 18 April 2010 in Brussels, when the organization's statutes were adopted by the 22 national pirate parties represented at the event.[39]

European Pirate Party

[edit]The European Pirate Party (PPEU) is a European political alliance founded in March 2014 which consists of various pirate parties within European countries.[40] It is not currently registered as a European political party.[41]

Parti Pirate Francophone

[edit]In Parti Pirate Francophone, the French-speaking Pirate Parties are organized. Current members are the pirates parties in Belgium, Côte d'Ivoire, France, Canada, and Switzerland.[42]

European Parliament elections

[edit]2009

[edit]| State | Date | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 7 June 2009 | 7.1 | 2 |

| Germany | 7 June 2009 | 0.9 | 0 |

2013

[edit]| State | Date | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia* | 14 April 2013 | 1.1 | 0 |

*Held in 2013 due to Croatia's entry into EU

2014

[edit]| State | Date | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom1 | 22 May 2014 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 22 May 2014 | 0.9 | 0 |

| Austria2 | 25 May 2014 | 2.1 | 0 |

| Croatia | 25 May 2014 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 25 May 2014 | 4.8 | 0 |

| Finland | 25 May 2014 | 0.7 | 0 |

| France | 25 May 2014 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Germany | 25 May 2014 | 1.5 | 1 |

| Greece3 | 25 May 2014 | 0.9 | 0 |

| Estonia4 | 25 May 2014 | 1.8 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 25 May 2014 | 4.2 | 0 |

| Poland | 25 May 2014 | <0.1 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 25 May 2014 | 2.6 | 0 |

| Spain | 25 May 2014 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Sweden | 25 May 2014 | 2.2 | 0 |

1Party only participated in North West England constituency

2PPAT is in alliance with two other parties: The Austrian Communist Party and Der Wandel. The alliance is called "Europa Anders" and also includes some independents in their lists

3with Ecological Greens

4PPEE are campaigning for an independent candidate (Silver Meikar) who supports the pirate program

2019

[edit]| State | Date | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 24 May 2019 | 330,844 | 14.0 | 3 |

| Finland | 26 May 2019 | 12,579 | 0.7 | 0 |

| France | 26 May 2019 | 30,105 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Germany | 26 May 2019 | 243,302 | 0.7 | 1 |

| Italy | 26 May 2019 | 60,809 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 26 May 2019 | 96,579 | 7.7 | 0 |

| Spain | 26 May 2019 | 16,755 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Sweden | 26 May 2019 | 26,526 | 0.6 | 0 |

2024

[edit]| State | Date | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 24 May 2024 | 184,091 | 6.20 | 1 |

| France | 26 May 2024 | 28,745 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Germany | 26 May 2024 | 186,773 | 0.4 | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 26 May 2024 | 68,085 | 4.92 | 0 |

| Spain | 26 May 2024 | 14,484 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Sweden | 26 May 2024 | 15,403 | 0.4 | 0 |

National elections

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (February 2024) |

| Country | Date | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 17 September 2006 | 0.6 | 0/349 |

| Germany | 27 September 2009 | 2.0 | 0/622 |

| Sweden | 19 September 2010 | 0.7 | 0/349 |

| United Kingdom | 6 May 2010 | 0.4 | 0/650 |

| Netherlands | 9 June 2010 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Finland | 17 April 2011 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Canada | 2 May 2011 | <0.1 | 0 |

| Switzerland | 23 October 2011 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Spain | 20 November 2011 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Greece | 6 May 2012 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Greece | 17 June 2012 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 15 March 2017 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Israel | 22 January 2013 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Iceland | 27 April 2013 | 5.1 | 3/63 |

| Iceland | 29 October 2016 | 14.5 | 10/63 |

| Iceland | 15 September 2017 | 9.2 | 6/63 |

| Iceland | 25 September 2021 | 8.6 | 6/63 |

| Iceland | 2 December 2024 | 3.02 | 0/63 |

| Australia | 7 September 2013 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Australia | 2 July 2016 | <0.1 | 0 |

| Australia | 18 May 2019 | TBA | 0 |

| Australia (as Fusion Party) | 21 May 2022 | TBA | 0 |

| Norway | 9 September 2013 | 0.3 | 0 |

| Germany | 22 September 2013 | 2.2 | 0 |

| Austria | 29 September 2013 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 20 October 2013 | 2.9 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 13 July 2014 | 1.3 | 0 |

| Sweden | 14 September 2014 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Israel | 17 March 2015 | <0.1 | 0 |

| Finland | 19 April 2015 | 0.9 | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 6 May 2015 | <0.1 | 0 |

| Germany | 24 September 2017 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 21 October 2017 | 10.8 | 22/200 |

| Iceland | 28 October 2017 | 9.2 | 6/63 |

| Slovenia | 3 June 2018 | 2.2 | 0 |

| Sweden | 9 September 2018 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 14 October 2018 | 6.5 | 2/60 |

| Israel | 9 April 2019 | <0.1 | 0 |

| Finland | 14 April 2019 | 0.6 | 0 |

| Belgium | 26 May 2019 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 9 October 2021 | 15.68 (in coalition with Mayors and Independents | 4 |

Elected representatives

[edit]Representatives of the Pirate Party movement that have been elected to a national or supranational legislature.

- Christian Engström, former MEP for Sweden (2009–2014)

- Amelia Andersdotter, former MEP for Sweden (2011–2014)

Since the 2021 Czech legislative election, the following 4 MPs are in office:

- Jakub Michálek, MP for Prague (2017–)

- Olga Richterová, MP for Prague (2017–)

- Ivan Bartoš, MP for Central Bohemia (2017–2021), MP for Ústí nad Labem (2021–), Leader of the Czech Pirate Party and Minister of Regional Development (2021–2024)

- Klára Kocmanová, MP for Central Bohemia (2021–)

The following served as MPs during the 2017–2021 term:

- Dana Balcarová, MP for Prague

- Ondřej Profant, MP for Prague

- Jan Lipavský, MP for Prague

- Lenka Kozlová, MP for Central Bohemia

- František Kopřiva, MP for Central Bohemia

- Lukáš Kolařík, MP for South Bohemia

- Lukáš Bartoň, MP for Plzeň

- Petr Třešnák, MP for Karlovy Vary

- František Navrkal, MP for Ústí nad Labem (2019–)[43]

- Tomáš Martínek, MP for Liberec

- Martin Jiránek, MP for Hradec Králové

- Mikuláš Ferjenčík, MP for Pardubice

- Jan Pošvář, MP for Vysočina

- Radek Holomčík, MP for South Moravia[44][45]

- Tomáš Vymazal, MP for South Moravia[46][47]

- Vojtěch Pikal, MP for Olomouc

- František Elfmark, MP for Zlín

- Lukáš Černohorský, MP for Moravian-Silesian

- Ondřej Polanský, MP for Moravian-Silesian

- Mikuláš Peksa, MP for Ústí nad Labem (2017–2019), then elected to European Parliament

Since the 2024 Czech senate election, the party has 1 senator:

- Adéla Šípová, Senator for Kladno (2020–)

The following are former senators:

- Libor Michálek, former Senator for Prague 2 (2012–2018)

- Lukáš Wagenknecht, former Senator for Prague 8 (2018–2024)

Since the 2024 EU elections, the party has 1 MEP:

- Markéta Gregorová, MEP for Czech Republic (2019–)

The following are former MEPs:

- Marcel Kolaja, MEP for Czech Republic (2019–2024)

- Mikuláš Peksa, MEP for Czech Republic (2019–2024)

Since the 2024 EU elections, the party does not have any national elected representatives. The former MEPs are as follows:

- Patrick Breyer, former MEP for Germany (2019–2024)

- Felix Reda, former MEP for Germany (2014–2019)

Since the 2024 parliamentary election, the party does not have any national elected representatives. The former MPs are as follows:

- Andrés Ingi Jónsson, MP for Reykjavík North (2016–), originally as a member of the Left-Green Movement, member of the Pirate Party (2021–2024)

- Arndís Anna Kristínardóttir Gunnarsdóttir, MP for Reykjavík South (2021–2024)

- Björn Leví Gunnarsson, MP for Reykjavík North (2016–2017) and later for Reykjavík South (2017–2024)

- Gísli Rafn Ólafsson, MP for Southwest (2021–2024)

- Halldóra Mogensen, MP for Reykjavík North (2016–2024)

- Þórhildur Sunna Ævarsdóttir, MP for Southwest (2016–2017), for Reykjavík South (2017–2021), and for Southwest (2021–2024)

- Birgitta Jónsdóttir, MP for Reykjavík South (2009–2013), and for Southwest (2013–2017)

- Ásta Guðrún Helgadóttir, MP for Reykjavík South (2015–2017)

- Einar Brynjólfsson, MP for Northeast (2016–2017)

- Eva Pandóra Baldursdóttir, MP for Northwest (2016–2017)

- Gunnar Hrafn Jónsson, MP for Reykjavík South (2016–2017)

- Helgi Hrafn Gunnarsson, MP for Reykjavík North (2013–2016, 2017–2021)

- Jón Þór Ólafsson, MP for Reykjavík South (2013–2015) and for Southwest (2016–2021)

- Smári McCarthy, MP for Southwest (2016–2021)

- Sven Clement, MP for Centre (2018–)

- Marc Goergen, MP for South (2018–)

- Ben Polidori, MP for North (2023–2024), left the party in 2024 and joined LSAP[48]

National parties

[edit]Outside Sweden, pirate parties have been started in over 40 countries,[49] inspired by the Swedish initiative.

See also

[edit]- Biopiracy – Harmful and/or unethical bioprospecting research

- Copyleft

- Criticism of copyright

- Internet freedom

- Piratbyrån

- Right to privacy

- Steal This Film

- The Pirate Bay

References

[edit]- ^ Fredriksson, Martin (2015). "Piracy & Social Change| The Pirate Party and the Politics of Communication". International Journal of Communication. 9: 909–924. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Jääsaari, Johanna; Šárovec, Daniel (2021). "Pirate Parties: The Original Digital Party Family". Digital Parties: The Challenges of Online Organisation and Participation. Cham: Springer. pp. 205–226. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78668-7_11. ISBN 978-3-030-78668-7.

- ^ Almqvist, Martin Fredriksson (2016). "Piracy and the Politics of Social Media". Social Sciences. 5 (3): 41. doi:10.3390/socsci5030041.

- ^ Burkart, Patrick (2014). Pirate Politics: the New Information Policy Contests. Cambridge: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262320146.

- ^ "About the PPI". Archived from the original on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Gerbaudo, Paolo (2019). The Digital Party: Political Organisation and Online Democracy. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745335797. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Beyer, Jessica L. (2014). "The Emergence of a Freedom of Information Movement: Anonymous, WikiLeaks, the Pirate Party, and Iceland". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 19 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12050.

- ^ Hartleb, Florian (2013). "Anti-elitist cyber parties?". Journal of Public Affairs. 13 (4): 355–369. doi:10.1002/pa.1480. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Fredriksson, Martin; Arvanitakis, James (2015). "Piracy, Property and the Crisis of Democracy". eJournal of EDemocracy and Open Government. 7 (1): 134–150. doi:10.29379/jedem.v7i1.365. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Fredriksson, Martin (2015). "Piracy & Social Change| The Pirate Party and the Politics of Communication". International Journal of Communication. 9: 909–924. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Dahlberg, Lincoln (2017). "Cyberlibertarianism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.70. ISBN 978-0-19-022861-3. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Simon, Otjes (22 January 2019). "All on the same boat? Voting for pirate parties in comparative perspective". Political Studies Association. 40 (1). SAGE Publishing: 38–53. doi:10.1177/0263395719833274. hdl:1887/85286. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023.

This indicates that instead of not appealing along left-right lines at all, pirate party's left-right appeal is context-dependent. Moreover, it is more closely related to sympathy for these parties than to party choice'. (Page 49)

- ^ Anderson, Nate (26 February 2009). "Political pirates: A history of Sweden's Piratpartiet". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Downie, James (24 January 2011). "What is the Pirate Party – and why is it helping Wikileaks?". New Republic. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Igler, Nadja (19 September 2006). "Österreichs Piraten sehen grün". Future Zone (in German). Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "European elections 2009: Sweden's Pirate Party wins a seat in parliament". The Telegraph. 8 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Edwards, Chris (11 June 2009). "Sweden's Pirate party sails to success in European elections". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Harris, Mark (11 August 2009). "Pirate Party UK sets sail". techradar. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Pirate Party launches UK poll bid". BBC News. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Barnett, Emma (11 August 2009). "Pirate Party UK now registered by the Electoral Commission". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Pirate Parties: From digital rights to political power". BBC News. 18 October 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Dowling, Siobhan (18 September 2011). "Pirate party snatches seats in Berlin state election". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Kulish, Nicholas (19 September 2011). "Pirates' Strong Showing in Berlin Elections Surprises Even Them". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Naughton, John (20 September 2011). "Could the Pirate party's German success be repeated in Britain?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Iceland vote: Centre-right opposition wins election". BBC News. 28 April 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Penny, Laurie (8 May 2013). "Laurie Penny on Iceland's elections: A shattered fairy tale". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Edick, Cole (2015). "The Golden Age of Piracy". Harvard International Review. 36 (4): 7–9 – via Ebscohost.

- ^ Collentine, Josef Ohlsson (26 May 2014). "All Pirate Party votes in the EU election". Pirate Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Nordenfur, Anton (6 January 2014). "Julia Reda tops German list to European Parliament". Pirate Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Reda, Felix (11 June 2014). "Election as Vice-President of the Greens/EFA Group". Felix Reda. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Steadman, Ian (29 January 2015). "The Pirate Party's lone MEP might just fix copyright across the EU". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ Hudson, Alex (19 March 2015). "The Pirates becomes the most popular political party in Iceland". Mirror. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "The Pirate Party is now measured as the biggest political party in Iceland". Vísir.is. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Björnsson, Anna Margrét (6 April 2016). "Almost half of Icelandic nation now want the Pirate Party". Iceland Monitor. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Andrea Platten | Senior Staff (14 April 2017). "Executive seats split between CalSERVE, Student Action in 2017 ASUC elections". The Daily Californian. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ Copley, Caroline (20 September 2009). "Germany's 'Pirate Party' hopes for election surprise". Reuters blog. Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Engström, Christian (2 June 2010). "Urging MEPs to withdraw their Written Declaration 29 signatures". Christian Engström blog. WordPress.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Pirate Parties International". Wiki of Pirate Parties International. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ "22 Pirate Parties from all over the world officially founded the Pirate Parties International". Pirate Parties International. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "Here comes the European Pirate Party". PirateTimes. 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Registered Parties". Authority for European political parties and European political foundations. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ "Pirate Party - Telecommunication Systems - 2729 - stkip-sera.download-soalujian.com". stkip-sera.download-soalujian.com. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Bc. Frantisek Navrkal". public.psp.cz. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Mgr. Radek Holomcik". public.psp.cz. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Bc. Frantisek Navrkal". public.psp.cz. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2020. [verification needed]

- ^ "Tomas Vymazal". public.psp.cz. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Mgr. Radek Holomcik". public.psp.cz. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2020. [verification needed]

- ^ "Defection complete: Former Pirate Party MP Ben Polidori joins LSAP: statement". today.rtl.lu. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Piratenpartij presenteert verkiezingsprogramma" (in Dutch). 3VOOR12 NL. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

External links

[edit]- Pirate Parties International – official website

- Pirate parties

- Anti-corruption parties

- Civil liberties advocacy groups

- Civil rights organizations

- Computer law organizations

- Copyright law

- Digital rights

- Direct democracy movement

- Free and open-source software organizations

- Freedom of expression organizations

- Freedom of information

- Freedom of speech

- Intellectual property activism

- Internet privacy organizations

- Internet-related activism

- Net neutrality

- Open government

- Participatory democracy

- Patent reform

- Political parties established in 2006

- Politics and technology

- Privacy organizations

- Transnational political parties