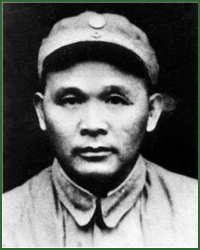

Xu Haidong

Xu Haidong | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 徐海東 |

| Born | June 17, 1900 Dawu, Hubei |

| Died | March 25, 1970 (aged 69) Zhengzhou, Henan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1925–1969 |

| Rank | Senior General of the People's Liberation Army |

| Commands | Corps commander of the Red Army, Senior Political Commissar of the Central China Bureau |

| Battles / wars | Northern Expedition, Autumn Harvest Uprising, Long March, Battle of Pingxingguan, Hundred Regiments Offensive |

| Awards | Order of Independence and Freedom, Order of Liberation, Order of the Army |

| Other work | Politician, Writer |

| Xu Haidong | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 徐海東 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 徐海东 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Xu Haidong (June 17, 1900 – March 25, 1970) was a senior general in the People's Liberation Army of China.

Xu was notable for leading his men from the front lines during the Chinese Civil War and Second Sino-Japanese War. His exploits earned him the nickname "Tiger Xu". He was wounded in battle nine times;[1] and, after contracting tuberculosis, was partially bedridden for the last eighteen years of his life. Xu opposed the radical policies of the Cultural Revolution, and was persecuted to death by the followers of Mao Zedong, Lin Biao and the Gang of Four.[2]

Early life

[edit]Xu was born in the village of Xujiaqiao, Dawu County, Hubei.[1] He was the sixth son in a family of ten children. His father was Xu Zhongben (徐重本) and his mother is only remembered by her family name, Wu (吴). When Xu Haidong was born, his father recognized that Xu's mother was too decrepit to nurse Xu, and requested that his mother throw Xu in a pond to drown. Xu's mother refused to kill Xu, and recruited her sister-in-law to nurse Xu.[3]

Xu's family was poor, and Xu did not receive any education until he was nine years old, when he was sent to a primary school where his uncle taught. Most of the students at the school were from rich families, and taunted Xu with the nickname "stinky tofu". When he was twelve, Xu was expelled from school after he injured a rich classmate who was bullying him.[3]

Because his parents were elderly they were unable to support Xu after his expulsion, and he was forced to return home and work at his family's kiln. Xu worked at the kiln for several years.[1] He also raised ducks and worked for periods at a factory to support himself and his family.[2] In 1921 Xu left home and became a professional soldier.[2]

Military career

[edit]Early career

[edit]After becoming a professional soldier, Xu worked for six years in the service of various military forces established by local warlords, and in the Nationalist Army. Xu joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1925, and participated in the Northern Expedition. After the Shanghai massacre of 1927, Xu escaped the Nationalist Army and begun organizing a guerrilla resistance unit in Hubei.[2]

In August 1927 Xu led a rebellion in his native district of Huangping known as the "Macheng Uprising". Xu's uprising was one of the Autumn Harvest Uprisings, a broader series of peasant rebellions ordered by the CCP Central Committee.[4] Xu was initially joined by 27 local farmers. Xu's first attack was successful in defeating the local militia, capturing local arms and supplies. Forces under Xu rose to 60 men before being defeated by government forces later in 1927. Government forces attempted to capture Xu, but he escaped.[3] With a handful of recruits, he founded the Seventh Red Army.[5] The Seventh Red Army remained on the move for the next few years, slowly growing in strength. In late 1929 Xu and other groups of communist guerillas active around the Hubei-Henan-Anhui border area founded the Eyuwan Soviet.[3][6]

Chinese Civil War

[edit]

After Joining the Red Army, Xu rose quickly within the military ranks of the Eyuwan Soviet.[1] Xu's first serious injury occurred in 1931, during a battle with Nationalist forces, when he was shot twice by a machine gun and put into a coma.[3] Xu was promoted to battalion commander, to regiment commander, to division commander, and by the early 1930s was the commander of the 25th Army. In 1934, the Nationalists' fourth encirclement campaign against the Eyuwan Soviet forced Xu and the 25th Red Army to retreat to the Shannxi-Sichuan border area.[1]

Xu was ordered to guard the rear of the Communist retreat during the Long March,[2] but he soon lost contact with the rest of the Red Army after the evacuation began, and he led his forces northward independently.[7] Xu's forces finally evacuated their own base area in September 1934, and reached the Wei River area, around the city of Xi'an, in June 1935.[2] After arriving in the communist base area of Shaanxi, Xu was named the commander of the 15th Army Corps.[1] By the end of the Long March, the Nationalists were offering 250,000 silver dollars for Xu's assassination.[8]

In February 1936, Xu and Liu Zhidan (who was killed in the operation) led 34,000 Communist guerillas into southwestern Shanxi, which was ruled by a Nationalist-aligned warlord, Yan Xishan. After entering Shanxi, Xu's forces enjoyed massive popular support; and, although they were outnumbered and ill-armed, succeeded in occupying the southern third of Shanxi in less than a month. Xu's strategy of guerrilla warfare was extremely effective against, and demoralizing for Yan's forces, who repeatedly fell victim to surprise attacks. Xu made good use of cooperation supplied by local peasants to evade and easily locate Yan's forces. When reinforcements sent by the central government forced Xu to withdraw from Shanxi, the Red Army escaped by splitting into small groups that were actively supplied and hidden by local supporters. Yan himself admitted that his forces had fought poorly during the campaign. After the Communists' retreat from Shanxi, Nationalist forces remained in Shanxi to deter further guerrilla activity.[9]

In 1936 Xu met the American journalist Edgar Snow, who visited Yan'an to interview notable Communist commanders. In his book, Red Star Over China, Snow wrote that, among the Communists in Yan'an, none were more famous or mysterious than Xu Haidong.[10]

Mao Zedong once said, "among the Chinese revolutionaries, no one has shed more blood than Xu Haidong's family", claiming that during the Nationalists' Communist Suppression Campaign, 66 of Xu's family members were killed by a Nationalist policy of exterminating Xu's clan.[citation needed]

Second Sino-Japanese War

[edit]

After the outbreak of the Second Sino Japanese War (1937–1945), Xu was named commander of the 344th Brigade of the 115th Division of the Eighth Route Army[1] (this was effectively a demotion).[3] Xu re-entered Shanxi in 1937 and participated in the Battle of Pingxingguan, in which a combined Nationalist-Communist force successfully delayed the Imperial Japanese Army from occupying Shanxi. After the Japanese advanced further into Shanxi, Xu continued to direct guerrilla operations in the mountainous countryside of Shanxi and western Hebei.[1]

In August 1938 Xu contracted tuberculosis, and was recalled to Yan'an to recover.[8][11] In September 1939 Xu joined forces under the command or Liu Shaoqi, serving as Deputy Commander of the New Fourth Army in central China, just north of the Yangtze River. Xu was successful in containing Japanese forces active in central China, contributing to communist attempts to establish an anti-Japanese base area in eastern Anhui.[1]

After a series of military victories in central China, Xu's tuberculosis became seriously debilitating (at one point putting Xu into a coma for three days), and he was forced to retire from fighting on the front lines in 1940.[12] Xu spent the rest of his life recuperating from his tuberculosis.[11] When the Chinese Civil War resumed in 1947, Xu was assigned to organize the Red Army's logistics, but was unable to complete the assignment owing to his medical condition.[13]

Later career

[edit]In 1955 Xu was one of ten officers awarded the rank of Senior General, or Da Jiang (大将), the first time that the rank of Senior General was established.[1] Xu maintained his employment within the People's Liberation Army, but was only semi-active due to his medical condition.[13] Xu was the chief editor of a book, the Military History of the Red 25th Army.

After the founding of the People's Republic, Xu disagreed with many of Mao Zedong's policies, but was not purged for decades. In the 1959 Lushan Conference, Xu sided with Peng Dehuai in opposing Mao's Great Leap Forward:[13] a radical economic programme that caused a man-made famine in which tens of millions of people starved to death.[14] Peng was purged for opposing Mao's economic policies, but Xu survived. In 1966, Xu again opposed Mao's radical policies at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. Xu especially disagreed with Mao's practice of attacking career Party members with long histories of supporting the Party and the army. In spite of his opposition to the Cultural Revolution, in April 1969 Xu was promoted as a full Party representative during the 9th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party.[13]

After the 9th Congress, Xu's opposition to the Cultural Revolution was recognized by China's radical Maoists. On October 25, 1969, Xu was purged as an "anti-Party element", and he and his family were forcibly expelled to Zhengzhou, capital of Henan. The followers of Mao Zedong, Lin Biao and the Gang of Four, allegedly directed the purging of Xu.[13] Xu's purging was physically and psychologically harsh, to the point of "torture". After his relocation, Xu was forced to live in a cold, damp house, and was denied medical treatment for his illness.[10] Xu died several months after being purged, on March 25, 1970.[13]

Xu was posthumously rehabilitated by Deng Xiaoping on January 25, 1979. He was one of eight senior military officers purged during the rule of Mao Zedong who were rehabilitated after Deng came to power.[13]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j PLA Daily

- ^ a b c d e f Wortzel and Higham 284

- ^ a b c d e f Xinhuanet 1

- ^ Wortzel and Higham 116

- ^ Benton 1992, p. 310.

- ^ Benton 1992, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Ch'en and Yang 460

- ^ a b Xinhuanet 2

- ^ Gillin 220–221

- ^ a b Guangming Daily

- ^ a b Hershatter 58

- ^ Xinhuanet 4

- ^ a b c d e f g Wortzel and Higham 285

- ^ Yang. Section I

References

[edit]- Benton, Gregor (1992). Mountain Fires: The Red Army's Three-year War in South China, 1934-1938. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Ch'en, Jerome, and Yang, Benjamin. "Reflections on the Long March". The China Quarterly. No. 111, September 1987. pp. 450–468. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967.

- "Xu Haidong: A Man of Great Service to the Chinese Revolution" Archived August 3, 2012, at archive.today. Guangming Daily. July 1, 2005. Retrieved December 3, 2011. [Chinese]

- Hershatter, Gail. The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- PLA Daily. "Xu Haidong: A Man Who has Rendered Outstanding Service to the Chinese Revolution". CPC Encyclopedia. September 30, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- Wortzel, Larry M. and Higham, Robin D. S. Dictionary of contemporary Chinese Military History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1999. ISBN 0-313-29337-6. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- "The Final Battle of General Xu Haidong". Xinhuanet. March 25, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2011. [Chinese]

- Yang Jisheng. "The Fatal Politics of the PRC's Great Leap Famine: the preface to Tombstone". Journal of Contemporary China. Vol.19, Issue 66. pp. 755–776. July 26, 2010. Retrieved December 7 2011.

- "Xu Haidong's family tragedy written in blood and tears". mil.sohu.com. Aug 23, 2014. [Chinese]

- 1900 births

- 1970 deaths

- Writers from Hubei

- Politicians from Xiaogan

- People's Liberation Army generals from Hubei

- Chinese military writers

- Chinese Communist Party politicians from Hubei

- Victims of the Cultural Revolution

- Chinese torture victims

- 20th-century Chinese writers

- People's Republic of China politicians from Hubei

- Burials at Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery