Wrights tunnel

SPCR # 17 outside the reconstructed north portal in Wrights in 1893, prior to the standard gauging of the line. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | South Pacific Coast Railroad |

| Coordinates | 37°08′17″N 121°56′54″W / 37.13806°N 121.94833°W (north portal) 37°07′34″N 121°57′49″W / 37.12611°N 121.96361°W (south portal) |

| Status | Abandoned |

| Operation | |

| Opened | May 10, 1880 |

| Closed | 1942 |

| Technical | |

| Length | 6,157 feet (1,877 m) |

| No. of tracks | 1 |

The Wrights Tunnel (also known as the Summit Tunnel, Tunnel 2, or Tunnel 1 after the daylighting of the Cats Canyon tunnel) is a railroad tunnel located in the Santa Cruz Mountains in Santa Clara and Santa Cruz Counties, California. Opened in 1880 after almost two years of construction involving numerous fatalities, the tunnel was at one point the longest tunnel in California and one the longest tunnels in the United States. It carried the tracks of the narrow gauge South Pacific Coast Railroad which ran trains from San Francisco to Santa Cruz until the railroad was acquired by Southern Pacific Railroad, which upgraded the tracks to standard gauge and continued operating trains through the line and its tunnel until a major storm in 1940 washed out certain sections of the track in the Santa Cruz Mountains. After two years without rail traffic, Southern Pacific abandoned the line. Subsequently, the United States Army Corps of Engineers collapsed both portals with explosives, destroying the northern portal in the process. The interior of the tunnel remains intact along with the south portal, but the conditions of the interior are unknown, particularly since the tunnel crosses the San Andreas Fault and no person has entered the tunnel in the aftermath of the Loma Prieta earthquake.

Construction

[edit]

After it was determined where the tracks of the future South Pacific Coast Railroad would go in the Santa Cruz Mountains in September 1878, construction of the tunnel commenced in the following October. Camp sites, occupied almost exclusively by Chinese laborers, developed at each portal. These sites led to the founding of Wrights, located directly adjacent to the north portal, and Highland, now known as Laurel, located adjacent to the south portal and Burns Creek.[1] Construction lasted around two years, during said time dozens of Chinese laborers were killed in multiple methane explosions caused by a methane leak within the tunnel, with the leak discovered on November 16, 1878. There was also crude oil leaking into the tunnel and coal deposits within the tunnel, with particularly the former contributing to the poor working conditions of the laborers. Lit candles were used by workers to burn off the unknown source of methane which availed to be fruitless, all while workers kept passing out due to the presence of this natural gas.[1]

Valentine's day explosion

[edit]On February 14, 1879, the methane within the north branch tunnel ignited, causing a massive explosion, killing fourteen Chinese workers and burning many other workers.

Thereafter, work was halted on the tunnel for three months while engineers worked to find a solution for the methane question. A crude air ventilation system was installed to pump fresh air into the incomplete tunnel. After this incident, the Chinese workers which resided in Wrights refused to reenter the tunnel, and different Chinese workers were brought to complete the work on the tunnel.[1]

June cave in

[edit]During the construction of the tunnel in June 1879, multiple creosote-treated redwood support beams in the tunnel ignited and spread to one another, compromising the structural integrity of that portion of the tunnel and causing that segment to cave-in. This set the project back by another two months.[1]

November explosion

[edit]After the previous two incidents in the same year, a pair of massive explosions occurred within the north branch of the tunnel at shortly before 12 am on November 17, 1879, killing 32 Chinese workers and injuring many other workers as well. The explosion was caused by a flame which was lit to blast the rock with explosives. However, that flame ignited the high amounts of methane in the air, with the subsequent explosion severely shaking the surrounding area. 2,700 feet (820 m) away at the portal, other workers felt the shock produced by the explosion, with 20 Chinese workers subsequently rushing into the tunnel with torches to rescue the injured. After traversing 1,700 feet (520 m) into the tunnel, another even more massive explosion occurred which essentially turned this half of the tunnel into a barrel, with a mountain of flame spewing out of the north portal. This explosion also destroyed the engine house and a shed within a hundred feet of the north portal.[2][3] Thereafter, the methane leak was discovered right by the north portal and a lantern was placed by it to flare off the methane to prevent another explosion.[1][3]

North portal collapse

[edit]

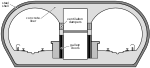

In the winter of 1893, the wooden north portal by Wrights collapsed after a winter storm. The portal is located in a gully where water from the mountains above collects and flows over the portal onto the tracks, bringing debris with it, often landing on the right of way and blocking it. With the collapse of the portal, a new concrete portal was installed with an adjacent spillway to resolve this issue. The new portal was also designed to be larger to provide room for the future standard gauging of the tracks.[1]

Narrow gauge operations

[edit]The tunnel opened to rail service on May 10, 1880. Passenger and freight service to Santa Cruz would pass through the tunnel, including the now famous Suntan Special. Much like how California State Route 17 becomes severely congested on weekends and during the summer in the present, tourists from the San Francisco Bay Area would flock to the Suntan special to spend a day or the weekend at the beaches of Santa Cruz, while others would take the train to whistle stops throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains to hike, picnic, or relax in the redwood forests, both of which have become less accessible to the average person since the abandonment of the railroad.[3] In 1895, H.S. Kneedler wrote the following about the line in his book Through Storyland to Sunset Seas:

The ride is one which rivals anything up the Shasta division or over the Sierras, for tho’ the mountain groups are not so massive, the effects are equally fine

Although the line was a major success for passenger rail to Santa Cruz, it was also a huge success for freight rail, with numerous quarries, sawmills, farmers, and other industries relying on the Summit Tunnel to transport their products to sea ports in Oakland and San Francisco.[3]

1906 earthquake and reconstruction

[edit]

Since the tunnel runs through the San Andreas Fault Zone near Wrights, the tunnel suffered severe damage from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, causing a one year closure of the tunnel and the railroad through the mountains. Because of the slip in the fault which caused the earthquake, the segments of the tunnel on the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate were displaced by five feet, requiring the formerly straight tunnel to incorporate a curve to be aligned again. The tunnel was repaired thereafter and widened to make way for standard gauge trains, which would begin using the tunnel in 1909. The western portal was also replaced due to the earthquake and a brick ceiling was installed for the first three hundred feet of the tunnel to prevent collapse from the sandstone present there. The brick ceiling is exposed to this day, with the collapse of the tunnel conducted further within when the tunnel was closed. The tunnel was also retimbered with redwood timbers by 1907.[1]

Standard gauge operations and abandonment

[edit]

After the reconstruction and retrofit of the existing tunnel, the tunnel continued to carry trains through the summit of the Santa Cruz Mountains without any major incidents. The tunnel operated for 33 years after its reopening and saw its last train in February 1940. After two years of inactivity on the rail line through the mountains, Southern Pacific abandoned segment of the railroad between Downtown Los Gatos in Los Gatos[4] and Olympia, along with the Summit Tunnel, in 1942. Both portals were blasted to preserve the interior of the tunnel, prevent trespassers, and for insurance reasons. The blast at the north portal caused the portal to partially collapse, a state which remains the same, and is, alongside the concrete piers over the Los Gatos creek, one of the last remnant of Wrights, with the town also vanishing due to the absence of the railroad, although it had been in decline for a couple decades at that point.[1][3] Prior to the blasting of the tunnel, the rails and timbers of value within the tunnel were removed by H. A. Christie under contract with the Southern Pacific Railroad.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Derek R. Whaley (December 22, 2017). "Tunnels: Summit (Tunnel 2)". Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "Santa Cruz Weekly Sentinel: Fatal Explosion". November 22, 1879. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Peter Arcuni (April 15, 2021). "The Story Behind Those Old Train Tunnels in the Santa Cruz Mountains". KQED Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Derek R. Whaley (April 5, 2019). "Railroads: Southern Pacific Branch Lines and Divisions". Archived from the original on February 13, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Circuit Rider". Santa Cruz Sentinel. April 19, 1942.

- Tunnels in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Railroad tunnels in California

- Tunnels completed in 1880

- Transportation buildings and structures in Santa Cruz County, California

- Transportation buildings and structures in Santa Clara County, California

- 1880 establishments in California

- Demolished buildings and structures in California

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1942

- Buildings and structures demolished by controlled implosion