Pacheco Pass Tunnels

Pacheco Pass Tunnels | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Pacheco Pass Tunnels are a planned set of tunnels to carry California High-Speed Rail across the Diablo Range in the vicinity of Pacheco Pass east of Gilroy, California. The tunnels will constitute the first mountain crossing constructed as part of California High-Speed Rail, connecting the San Francisco Bay Area and Central Valley portions of the system.[1]

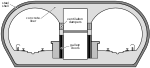

The tunnels are planned to consist of two 28-foot (8.5 m) diameter tunnels.[2] At 13 miles (21 km) long the main tunnel is expected to become North America’s longest rail tunnel, surpassing the Mount Macdonald Tunnel in British Columbia.[1][2] An additional 1.5-mile (2.4 km) rail tunnel is planned to be constructed to the west. The tunnels are expected to cost around $5 billion.[2]

The right-of-way runs parallel to the existing Pacheco Tunnel and Santa Clara Tunnel, two contiguous water tunnels connecting the San Luis Reservoir into Santa Clara County.[2][3]

History

[edit]In 2004, two options were in consideration for the Diablo Range crossing: the Pacheco Pass option and a "direct" 31-mile (50 km) tunnel between San Jose and Merced significantly north of the Pacheco Pass.[3] A route through the Altamont Pass even further north was also considered.[4] In July 2008 the Pacheco Pass option was selected.[5] The reasons were that the Altamont alignment would require the track to split west of the pass to serve different parts of the Bay Area, would require a new crossing of the San Francisco Bay using a rehabilitated Dumbarton Rail Bridge or a new bridge or tunnel nearby, and would require more homes to be seized by eminent domain. The Pacheco alignment, however, would increase travel times between the Bay Area and points north of Merced, and passes through more environmentally sensitive areas.[4][6][7]

A November 2009 court ruling however reopened the environmental review process.[5] The suit was brought by the cities of Palo Alto, Menlo Park, and Atherton, which opposed elevated high-speed rail tracks running through them and preferred the Altamont Pass route. By September 2010, the rail authority had completed extra studies and reapproved the same route. However, a November 2011 ruling again overturned the approval.[6] The Pacheco Pass alignment was upheld by the California Court of Appeal for the Third District in July 2014.[8][9]

In June 2017, the California High-Speed Rail Authority began performing geological sampling of the tunnel area, with a design-build contract expected to be awarded in 2018.[2] The rock under Pacheco Pass is known to be of the Franciscan Assemblage formation.[2][3][10]

On February 12, 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom in his first State of the State address announced that parts of the system outside the Central Valley segment from Bakersfield to Merced would be indefinitely postponed, including the Pacheco Pass Tunnel.[11] Nonetheless, the CaHSRA board chose the tunnel alignment as their preferred build alternative in September 2019.[12] As of 2020[update] this section of the system has a projected start of service in 2031.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Meachan, Jody (January 30, 2017). "High-speed rail considers 2 record-setting options for Pacheco Pass tunnel". Silicon Valley Business Journal. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Meacham, Jody (June 14, 2017). "What's under Pacheco Pass and what's it mean for California high-speed rail?". Silicon Valley Business Journal. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Tunneling Issues Report" (PDF). California High-Speed Rail Authority. January 2004. pp. 16, 22–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Cabanatuan, Michael (November 15, 2007). "High Speed Rail Authority staff advises Pacheco Pass route to L.A." SFGate. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "Appendix G: Draft Alternatives Analysis Public Participation Report for the San Jose to Merced High-Speed Train Project EIR/EIS" (PDF). California High-Speed Rail Authority. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Mike (November 10, 2011). "Judge: Bullet train must ax route through South Bay, Peninsula, for now". The Mercury News. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Lew, Alexander (December 22, 2007). "California High Speed Rail's Route Debate Is Over". Wired. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Sheehan, Tim (July 24, 2014). "Appellate court upholds environmental work for high-speed rail via Pacheco Pass". Fresno Bee. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "Third Court of Appeal: Atherton v. CaHSRA". DocumentCloud. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Rush, Jim (November 17, 2016). "Connecting California: High-Speed Rail System to Enhance Statewide Transportation Network". Tunnel Business Magazine. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Willon, Phil; Luna, Taryn (February 12, 2019). "Gov. Gavin Newsom pledges to scale back high-speed rail and twin-tunnels projects in State of the State speech". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Brinklow, Adam (September 20, 2019). "California High-Speed Rail board votes to bring trains to San Francisco". Curbed. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Thadani, Trisha (July 10, 2020). "Plan for high-speed rail rolls out for San Francisco to San Jose - but with little cash". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 12, 2020.