Wood type

In letterpress printing, wood type is movable type made out of wood. First used in China for printing body text, wood type became popular during the nineteenth century for making large display typefaces for printing posters, because it was lighter and cheaper than large sizes of metal type.[1]

Wood has been used since the earliest days of European printing for woodcut decorations and emblems, but it was not generally used for making typefaces due to the difficulty of reproducing the same shape many times for printing. In the 1820s, Darius Wells introduced mechanised wood type production using the powered router, and William Leavenworth in 1834 added a second major innovation of using a pantograph to cut a letter's shape from a pattern. This made it possible to mass-produce the same design in wood repeatedly.[2][3][4][5][6] Wood type was manufactured and used worldwide in the nineteenth century for display use.[5]

In the twentieth century lithography, phototypesetting and digital typesetting replaced it as a mass-market technology. It continues to be used by hobbyists and artistic printers.

Pre-industrial wood type

[edit]

Both in China and Europe, printing from a woodblock preceded printing with movable type.[12]

Along with clay movable type, wooden movable type was invented in China by Bi Sheng in 1040s CE/AD, although he found clay type more satisfactory, and it was first formally used to print by Wang Zhen.[12][13] Wood type was hand-carved to make individual types for the very large character set of Chinese.[12][14] Clay type and metal type were also used in printing in China.[15] The problem with wood and clay types was that they could not be made to accurate dimensions, leading to metal type being adopted from the late fifteenth century.[14][12] Manufacturing, selecting and redistributing sorts for a large character set was cumbersome, and much printing in China continued to be made from custom-cut woodblocks of entire pages of text, rather than from movable type.[12]

In Europe, woodblock printing precedes European movable type printing, and the block book appeared in Europe around the same time as letterpress printing.[16] However, a major disadvantage of woodcut lettering is that once made by wood engraving, it could not be easily duplicated by casting, whereas metal casting could be used to quickly create many metal copies of the same letter, and with the smaller character set of European languages it was practical to cast type for every letter needed. European printing from the beginning used cast metal type.[17][a]

In European printed books, wood engraving was used for both decorations and for large lettering, like titles.[22] With care, it was possible to duplicate woodblocks by casting in sand, a technique known to have been used by Hendrik van den Keere to create his large types.[19] According to John A. Lane "the duplication of woodblocks by sandcasting is documented in 1575, probably goes back further, and ... duplicated decorated initials became common in the Netherlands around 1615."[23]

Large sandcast metal types for printed posters became popular in London around the mid-eighteenth century. James Mosley comments that "there is evidence that English typefounders only began to make big letters for posters and other commercial printing towards 1770, when Thomas Cottrell made his 'Proscription or Posting letter of great bulk and dimension' and William Caslon II cast his 'Patagonian' or 'Proscription letters'"[24] and that "there is probably a prehistory of wood types in big letters cut by hand, especially among provincial printers, but there is no evidence that wood letter was widely used until machine-cut types were introduced."[25]

In the early nineteenth century, London became a centre of development in bold display typefaces, the arrival of the printed poster spurring demand for bold new types of letter like the fat face and later the slab serif. However, these types were initially made in metal.[26] In 1810, William Caslon IV introduced "sanspareil" matrices, made like a stencil by cutting out the letter in sheet metal and riveting it to a backing plate. This produced much sharper type than sandcasting and was easier to use; it was quickly copied.[27] The large metal types produced were cast with hollows in them to reduce the weight.[28][29] Mosley and Justin Howes have documented some cases in the early nineteenth century where woodblock lettering was used shortly before metal type became available in the same styles; heavy roman types on lottery advertising before the arrival of fat face types,[26] and later a slab serif woodblock a few years before the first known printing type.[29]

At the start of the nineteenth century, complex decorated types and ornaments were cut in wood and metal and multiplied by methods including stereotyping and "dabbing", in which a woodcut was struck into molten metal on the verge of solidifying to form a mould.[31][32][33][34][35][36] One type foundry particularly known for decorated designs was the London foundry of Louis John Pouchée, active by 1818 to 1830;[37][35] many of the foundry's wooden patterns are preserved.[36][38][39][b] Modern printing historians Giles Bergel and Paul Nash have experimented with the technique; Bergel reports that "perhaps the most counter-intuitive feature of the process is the fact that wooden blocks can survive direct contact with molten metal. Apart from some scorching around the edges and some cracking (perhaps made when prising them loose rather than from the heat) the blocks were undamaged and could be dabbed over and over again."[40]

Machine-cut wood type

[edit]

Modern wood type, mass-produced by machine cutting rather than hand-carved, was invented by Darius Wells (1800–1875), who published his first known catalogue in New York City in 1828.[1][42][43][44][45] He introduced the lateral router to cut out wood type more quickly than handcarving.[1][46][47]

William Leavenworth in 1834 introduced the pantograph, allowing the same form to be reproduced from a pattern, and manufactured wood type in Allentown, New Jersey.[48][49][50] A pantograph has remained a standard way of making wood type, although several other methods have been used such as die-cutting[51] and making the letter as a thin sheet glued to a backing material.[1][42][52]

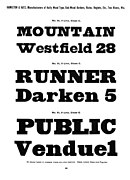

Some pages from Leavenworth's only surviving specimen, now in the New York Public Library, are shown below.[49]

-

Condensed Gothic (sans-serif)[c]

-

Gothic (sans-serif) and chamfered Gothic types

-

"Italian" (reverse contrast, see below)

Manufacturers of wood type were also established in France, Germany,[5][54] Britain and other countries.[55]

Mature industry

[edit]

In the mid-nineteenth century there were numerous wood type manufacturers in the United States. All the significant manufacturers were based in the Northeast and Midwest, many around New York City and in Connecticut.[56] The market for wood type was apparently limited and most businesses had side-lines as dealers in other printers' equipment, or making other wooden goods.[57] One of the larger firms until the 1880s was the company of William H. Page, near Norwich, Connecticut. Wood type competed with lithography and stencils in the market for display typography.[58][59][60]

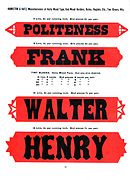

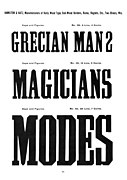

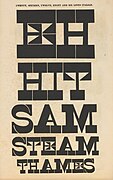

Common type styles included the slab serif, fat face, sans-serif, reverse-contrast or "French Clarendon",[61] and other genres such as "Tuscan" (spikes on the letter), "Grecian" (chamfered)[62] and ornamented forms.[63][64] (The use of fictitious adjective names for newly invented type styles was common with wood type manufacturers but not invented by them, for example in London Vincent Figgins had called his first slab-serif "Antique" around 1817 and the Caslon foundry's first reverse contrast typeface around 1821 was given the probably fictitious name "Italian".[2][65]) Types were made in extreme proportions, such as ultra-bold and ultra-condensed.[66][67] For Bethany Heck, "wood type in the US was pioneered by mad scientists who strained good taste and legibility in an attempt to cover the broadest range of ornament, width and weight".[6] "Chromatic" types were also made for printing colour separation, showing the delicacy that could be achieved.[68]

-

Ornamented types, 1859 specimen, Wm. H. Page and Co.

-

Chromatic colour separation Pointed and Tuscan wood type, Wm. H. Page & Co., 1874 specimen[69]

Wood type had distinctive characteristics compared to metal type. The demand for novelty led to an arms race of new styles of novelty type designs, and because each type was individually cut by pantograph from a pattern, types could be offered in a wide range of sizes.[70] Wood type styles were sold in a wide range of widths from condensed to ultra-wide, and Hamilton offered to supply at regular prices any width desired in between its standard widths.[71] Robert James DeLittle, the last owner of the DeLittle wood type cutters in York, England, explained in 2000 that sometimes very condensed letters were needed for theatre posters because "If you were more important than the other chap, your name had to be in larger letters. If you were unfortunate enough to have a long-winded name you had great difficulty in fitting it into those narrow theatrical bills."[72][67] As noted above, multiple types were often made for the multiple layers of a design to be printed using colour separation.[69] As wood type was made for large sizes, it was often made with very narrow sidebearings between letters, so spacing material had to be inserted to achieve the desired spacing between characters.[73] Digital typeface designer Anatole Couteau comments: "in wood type...due to how the wooden blocks are cut, spacing is typically so tight that you constantly have to do kerning."[74][75]

Although apparently diverse in appearance, nineteenth century wood types tended to be ornamented variations on the same basic modularised design principles, similar to nineteenth century Didone text typefaces.[76] Nineteenth-century types were based on a system of keeping the capitals very similar in width, seen for example in the "tucked-under" leg of the R.[77][78][d] This model was quite different from Roman square capitals, where the capitals are quite different in width.[79]

Wood type manufacture was particularly common in the United States, and its companies made type in other languages for export. By the 1870s, missionaries working in China had commissioned type for printing posters, and wood type was also made for Russian and Burmese for export.[80] Besides this, American manufacturers made German blackletter, Greek and Hebrew types catering to the large immigrant communities.[80][81][82]

In 1880, J. E. Hamilton founded the Hamilton Manufacturing Company in Two Rivers, Wisconsin. His company grew rapidly to take over the American industry. Hamilton gained its initial advantage by introducing a new method of making wood type very cheaply: the wood letter was cut out and then attached to a backing of a block of cheaper wood.[83] Around 1890, Hamilton switched to the standard router method of cutting wood type as a single block.[83] It also benefited from an effective distribution network and proximity to the growing western market.[84][85] From 1887 to 1909 it took over most of its competitors.[1][86][87] It continued to make wood type until 1985.[84] The surviving materials from the company are now preserved at the Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum, also in Two Rivers.[1][88][87][89]

Some types from Hamilton are shown below:

-

Blackletter type

-

Slab serif

-

Condensed sans-serif

-

Slab serif with curving terminals

-

"French Clarendon" (reverse-contrast)

-

"Streamer" chromatic type, with type in front of a banner

-

Tuscan French Clarendon type

-

Grecian (chamfered) slab-serif type

According to S. L. Righyni, in the late inter-war period in Britain, the standard letterform on newsbills posted by newsagents was "the sans-serif wooden letter-form", especially bold condensed sans-serifs from Stephenson Blake, although the Daily Express used Winchester Bold and The Times had a custom design similar to Kabel Bold Condensed.[90] (Although wood type was used for news bills and posters, large newspaper headlines were rare in British newspaper printing until well into the twentieth century.[91])

Wood type sellers

[edit]United States

United Kingdom

- DeLittle[95][96]

- H. W. Caslon[97]

- H. M. Sellers[98]

- Stevens Shanks

- Day & Collins[99]

- Stephenson Blake[90][100]

Germany

France

Switzerland

- Roman Scherer[104]

Brazil

- Funtimod[105]

India

Legacy technology

[edit]

During the post-war period, wood type poster printing was displaced by new technologies like offset lithography and phototypesetting. Reproductions of wood type with their resonance of times past were offered by phototypesetting companies such as Photo-Lettering Inc. and Haber Typographers, and used in the 1960s by designers such as Bob Cato and John Berg,[108] and later Paula Scher and Louise Fili.[109][110] Wood type has remained in use longer in India, where as of 2024 it continued to be used for printing shopping bags.[111] Artistic printers like Jack Stauffacher and retro print shops such as Hatch Show Print carried on using wood type, finding that it was a cheap way to achieve creative effects.[112][113][114] (For wood type historian Rob Roy Kelly, the aesthetic quality of wood type manufacturers declined in the twentieth century; Nick Sherman and Frode Helland have commented on a staggeringly bad rendition of Futura in Hamilton's 1951 specimen that features inconsistent stroke weights, the dot on the i and j at different heights, and the 8 in the specimen printed upside down.[115][116][117][118])[e]

The use of wood type styles is commonly associated with the American Frontier or "Wild West". These typefaces are seen as classic western Americana. This is because of its cinematic and decorative appearance: wood type style-lettering was very popular in Westerns giving it an association with the American west, and are used frequently to depict that aesthetic, from theme parks to bars.[120][121]

In the 1950s, Rob Roy Kelly, an American graphic design teacher, became interested in the history of wood type and built up a large collection from sources like old print shops and printers' families.[103][122] He published a history of the industry, American Wood Type, 1828–1900 in 1969.[123][124][125] His collection, now at the University of Texas at Austin,[126] has been studied by other historians of wood type such as David Shields.[127][128][129][130][131]

Digital fonts

[edit]Many digital fonts based on wood type display faces have been published, benefiting from the plentiful source material and accessibility of images, for example Kelly's book.[6][109] For example, when Adobe were developing a line of original typefaces in the early 1990s they created a large number of digital fonts based on wood types using proofs supplied by Kelly, which were named after types of tree.[132][133]

Notes

[edit]- ^ There is minimal surviving evidence of the first printing methods, but the opinion of historians such as Talbot Baines Reed, Alfred F. Johnson, Harry Carter and James Mosley is that the earliest printing methods were very similar to those used in metal type until mechanisation in the nineteenth century, using punches, matrices and moulds to make and cast metal type.[17] It has been suggested sometimes by historians such as Paul Needham that in early printing other methods were used such as casting stereotype plates in plaster, which has itself been disputed by James Mosley who has suggested an alternative explanation of type being bound together with wire; in any case it is certain that no alternative method lasted long in use, and that in European printing from metal type was the norm.[18]

- ^ Some websites have assumed that Pouchée engraved these faces himself. This is unlikely to be correct as he was not an engraver but a businessman, he was the owner of a restaurant and then a coal merchant before he became a typefounder. The blocks do not have any engravers' names on them; Mosley assumes that they are the work of multiple engravers based on the mixture of styles and notes that a few similar hand-carved wooden types have come to light in England from other sources.[35]

- ^ This type has been digitised by Barbara Lind for Adobe Systems as Poplar.[53]

- ^ In Tubbs' Uniform Set Gothic type, a full specimen of which is not known to survive, an advert seems to claim that all the capital letters had the same width apart from I and M and W (the latter two themselves the same width), although it did claim that its manufacturing methods were unique.[71]

- ^ Not a unique criticism: Eva Silvertant comments of the H. M. Sellers 1965 specimen that "some wood-type faces look like they're cut from memory...[it] isn't ‘quite' Gill Sans Bold."[119]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Shields, David. "What Is Wood Type?". Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shields, David (2008). "A Short History of the Italian". Ultrabold: The Journal of St Bride Library (4): 22–27. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Ichiyama, Dennis. "2004 Friends of St Bride conference proceedings: How wood type tamed the west". Stbride.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Old West Reward Posters". Wildwestweb.net. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Pané-Farré, Pierre (8 March 2021). "The case of Will & Schumacher". Klim Type Foundry. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Heck, Bethany (25 August 2018). "Champion Gothic". Font Review Journal. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Pires, Candice (2 April 2016). "A-Z living: an inside look at typographer Alan Kitching's home". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ ""I always try to have some logic to the job, to the work": we interview letterpress legend Alan Kitching". It's Nice That. 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "Alan Kitching on Press at The Guardian | Newspaper Club". blog.newspaperclub.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Waters, John L.; Kitching, Alan (2016). A life in letterpress. Lawrence King. ISBN 978-1780674810.

- ^ Sinclair, Mark (22 April 2016). "Alan Kitching a life in Letterpress". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Taylor, Insup; Taylor, Martin M. (1 January 1995). Writing and Literacy in Chinese, Korean and Japanese. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-90-272-1794-3. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Lu, Yongxiang (10 October 2014). A History of Chinese Science and Technology: Volume 2. Springer. pp. 214–220. ISBN 978-3-662-44166-4. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Deng, Yinke (3 March 2011). Ancient Chinese Inventions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0-521-18692-6. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Wilkinson, Endymion Porter (2000). Chinese History: A Manual. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 449–453. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Cowley, Des; Williamson, Claire (2007). The World of the Book. The Miegunyah Press. pp. 19–22. ISBN 9780522853780.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carter, Harry (2008). A View of Early Typography Up to About 1600. Hyphen Press. pp. 6–12. ISBN 9780907259213.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Fallen and threaded types". Type Foundry. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Enschedé 1978, p. 34.

- ^ Vervliet & Carter 1972, pp. 6–11.

- ^ [Specimen characterum]. Christophe Plantin. c. 1585. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Vervliet, Hendrik D. L. (2008). The palaeotypography of the French Renaissance : selected papers on sixteenth-century typefaces. Leiden: Brill. p. 240. ISBN 9789004169821.

- ^ Lane, John A. (27 June 2013). "The Printing Office of Gerrit Harmansz van Riemsdijck, Israël Abrahamsz de Paull, Abraham Olofsz, Andries Pietersz, Jan Claesz Groenewoudt & Elizabeth Abrahams Wiaer c.1660–1709". Quaerendo. 43 (4): 311–439. doi:10.1163/15700690-12341283.

- ^ Mosley 1990, p. 9.

- ^ Mosley 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mosley 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Mosley 2003, p. 103.

- ^ Mosley 2003, p. 112.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mosley, James. "The Nymph and the Grot: an Update". Typefoundry blog. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Shields, David. "George Fash Nesbitt was born 214 years ago on January 13, 1809...Nesbitt's 1841 wood type specimen catalog remains the first know example showing chromatics. The Butler Library at Columbia University holds the only known surviving copy of the 1841 catalog". Instagram. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Big brass matrices: a mystery resolved?". Type Foundry (blog). Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Big brass matrices again: the Enschedé 'Chalcographia' type". Type Foundry (blog). Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Dabbing, abklatschen, clichage..." Type Foundry (blog). Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Mosley 1990, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mosley 1993.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ornamented types: a prospectus" (PDF). imimprimit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Coles, Stephen (7 May 2016). "Ornamented Types Introduction and Prospectus". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Daines, Mike. "Pouchee's lost alphabets". Eye Magazine. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ "Ornamented Types". Letterform Archive. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Bergel, Giles (4 June 2016). "Printing cliches". Printing Machine. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Moore, Scott (17 September 2018). "Cutting New Wood Type With a Historic Pantograph". YouTube. Ann Arbor District Library. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kelly 1969, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Trumbell, Levi R. (1882). A History of Industrial Paterson: Being a Compendium of the Establishment, Growth and Present Status in Paterson, N.J., of the Silk, Cotton, Flax, Locomotive, Iron and Miscellaneous Industries : Together with Outlines of State, County and Local History, Corporate Records, Biographical Sketches, Incidents of Manufacture, Interesting Facts and Valuable Statistics. Higginson Book Company. ISBN 978-0-8328-6070-6. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ The Great Industries of the United States: Being an Historical Summary of the Origin, Growth and Perfection of the Chief Industrial Arts of this Country: by Horace Greeley ... and Other Eminent Writers, Etc. Hartford: J. B. Burr & Hyde. 1872. pp. 1265–1271. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Kelly 1969, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Clayton, W. Woodford; Nelson, William, eds. (1882). History of Bergen and Passaic Counties, New Jersey: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men. Everts & Peck. p. 489. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Griffin, Dori (30 December 2021). Type Specimens: A Visual History of Typesetting and Printing. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-350-11662-7. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Johnson's Universal Cyclopaedia: A Scientific and Popular Treasury of Useful Knowledge. A. J. Johnson. 1886. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Specimen of Leavenworth's patent wood type, manufactured by J. M. Debow. Allentown. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Leavenworth, Elias W. (1873). A Genealogy of the Leavenworth Family in the United States: With Historical Introduction, Etc. S. G. Hitchcock & Company. pp. 239–240. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Schneider 2015, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Shields 2022, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Poplar". Adobe Fonts. Adobe Systems. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Pané-Farré, Pierre. "Panorama : A reassesment [sic] of 19th century poster type". École supérieure d'art et de design d'Amiens. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Kelly 1969, p. 34.

- ^ Shields 2022, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kelly 1969, pp. 61–62.

- ^ MacMillan, David. "Why No "Type Designers" Here?". Circuitous Root. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Pané-Farré, Pierre (6 April 2020). "Type Design Prize: Affichen-Schriften FSL Pierre Pané-Farré". YouTube. Tokyo TDC. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Mosley, James. "Lettres à jour: public stencil lettering in France". Typefoundry (blog). Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Heller, Steven (June 2017). "The Birth of a Wood Type". Print. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan. "Grecian Fonts: A Miscellany". Hoefler & Co. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Lupton, Ellen (15 April 2014). Thinking with Type. Chronicle Books. p. 23. ISBN 9781616890452.

although Bodoni and Didot fuelled their designs with the calligraphic practices of their time, they created new forms that collided with typographic tradition and unleashed a strange new world, where the structural attributes of the letter-serif and stem, thick and thin strokes, vertical and horizontal stress-would be subject to bizarre experiments...Fonts of astonishing height, width and depth appeared: expanded, contracted, shadowed, inlined, fattened, faceted and floriated. Serifs abandoned their role as finishing details to become independent architectural structures, and the vertical stress of traditional letters canted in new directions.

- ^ Shields, David. "Etna – A History of 'Aetna' Typefaces". Mark Simonson Studio. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Frere-Jones, Tobias. "Scrambled Eggs & Serifs". Frere-Jones Type. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Coign". Colophon Foundry. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

Coign is an extensive study of condensed forms based on the DeLittle type foundry's Elongated Sans. DeLittle's type — extending far beyond the realms of legibility — challenges conventional letterforms, pushing the notion of what is 'condensed' to the absolute limit.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Coign; the most condensed font ever (probably)". Medium. Colophon Foundry. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Shields, David. "Chromatic Gothic Paneled". Wood Type Research. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Specimens of chromatic wood type, borders, etc. manufactured by Wm. H. Page & Co. Greeneville, Connecticut: Wm. H. Page & Co. 1874. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Ulrich, Ferdinand. "From Compressed Light to Extended Ultra". FontShop. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shields, David. "Unit Gothic & Uniform Set Gothic: wood type as precursor". Wood Type Research. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Last of the old type". The Press. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Sherman, Nick. "The Birth of a Wood Type". Hamilton Wood Type Museum. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Wälchli, Tan. "Emil Ruder: A Tool for Teaching". Lineto. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

Couteau: 'My teacher at École Estienne in Paris, Franck Jalleau, liked to provoke people by saying that kerning is only necessary for poorly spaced fonts. But in wood type, this is entirely different. Due to how the wooden blocks are cut, spacing is typically so tight that you constantly have to do kerning.' Strips of type metal in various widths were inserted between each pair of letters on press. This was feasible in the days of wood type, when often only a couple of dozen letters were used.

- ^ Spiekermann, Erik. "Making Display Type at p98a in Berlin". p98a. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Majoor, Martin (29 November 2004). "My Type Design Philosophy". Typotheque. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Verlomme, Malou (27 April 2020). "Meet Macklin". Vimeo. Monotype. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ Gehlhaar, Jens. "Neuwelt: An optimistic transatlantic sans serif type family — Jens Gehlhaar". Jens Gehlhaar. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Johnston, Edward. Writing, Illuminating and Lettering. p. 233.

[In the] nineteenth-century style...it was customary to make every letter occupy the same space and look as much like its neighbour as possible.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kelly 1969, p. 76.

- ^ Specimens of Wood Type [blackletter types]. Greeneville: Wm. H. Page (digitisation: St Louis Public Library). 1859. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Shields 2022, p. 308.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shields 2022, p. 43.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shields 2022, p. 37.

- ^ "History". Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Shields, David. ""The Wood Type business should go West…" An 1887 letter from William H. Page to W.B. Baker". Wood Type Research. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cheng, Jacqui. "Wood Stock". The Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Creative Destinations: Two Rivers, Where Wood Type Still Makes a Big Impression". Fastcodesign.com. 12 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Simonson, Mark (18 August 2022). "Hamilton Wood Type Museum". Mark Simonson. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Righyni, S. L. (1946). "News Bills: A Retrospectus". Alphabet & Image (2): 34–49.

- ^ Reilly, Lucas (4 January 2018). "Quartz Weekly Obsession: Victorian Newspapers". Quartz. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Kelly 1969, p. 37.

- ^ Kelly 1969, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Kelly 1969, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Bolton, Claire (1988). DeLittle, 1888–1988 : the first years in a century of wood letter manufacture, 1888–1895. Alembic Press. ISBN 9780907482291.

Wood type was first made in the United States in 1828 and by the mid-1840s was being used in Britain...the first British firms began cutting wood type during the 1860s. DeLittle entered the field comparatively late but his idea was to specialise [in] 'white-letter' wood type.

- ^ DeLittle's Wood Type. York: DeLittle. 1966. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Specimens of Wood Letter, Ornaments, Borders, etc. London: H. W. Caslon and Co. Ltd. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Wood Letter Specimens. H. M. Sellers & Co. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Wood Type, Printing and Bookbinding Materials. London: Day & Collins. 1897. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Wood Letter, Printers' Joinery, Machinery. Sheffield and London: Stephenson Blake. 1915. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Sowersby, Kris. "Mānuka design information". Klim Type Foundry. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Plakat-schriften. Schriftschneide-Anstalt von Will & Schumacher in Mannheim... (in German). Mannheim: Will & Schumacher. 1865. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kelly 1969, p. 7.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan. "St. Patrick's Type". Hoefler & Co. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Burian, Veronika; Scaglione, José. "Interview: Catalpa Wood Type". TypeTogether. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Basrai, Sabiha (12 September 2023). "Type History Toolkit, Part 2: De-Centering the Latin Letter in Design Education". Letterform Archive. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Diamond Wooden Type Works specimen, ca. 1975". Flickr. Diamond Wooden Type Works (digitisation: Letterform Archive). 18 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Coles, Stephen (21 December 2015). "Bob Dylan – The Times They Are A-changin' album art". Fonts In Use. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

Haber...provided phototype versions of Morgan wood type, including Nesbitt's Gothic, for much of the New York design scene

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoefler, Jonathan (4 January 2018). "Jonathan Hoefler 2017 Wayzgoose Presentation at Hamilton Wood Type & Printing Museum". YouTube. Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Scher, Paula (2020). Twenty-Five Years at the Public. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 39–42. ISBN 9781616899349.

When I left CBS Records, I had asked Haber Typographers for large-scale prints of the complete alphabets, numbers and punctuation for all of the wood fonts from the foundry. All through the '80s, I repeatedly xeroxed the fonts and used them on book covers and in magazines.

- ^ George, Tanya. "Diamond Wood Type Works". Letterform Archive.

- ^ Kelly 1969, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Simonson, Mark (18 August 2022). "Introducing HWT Konop". Mark Simonson Studio.

a modern letterpress printer...tends to be more interested in self-expression and artistic effects

- ^ Motycka, Eli (18 August 2022). "Fine Print: The Letterpress Artists Visually Defining Nashville". Nashville Scene. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Helland, Frode. "The best Futura". Twitter. Monokrom Schriftvorlag. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Sherman, Nick (2012). "The Design of Type Specimens". The Shelf. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

A seemingly random mishmash of characters were used to present an already-wonky cut of Futura in Hamilton Manufacturing Company's wood type catalog #25, 1951.

- ^ Devroye, Luc. "Hamilton Holly Wood Type Co. (or: Hamilton Manufacturing Company) [James Hamilton]". Type Design Information Page. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Sherman, Nick (28 November 2022). "Franklin Gothic Goes on Forever with Nick Sherman". YouTube. Cooper Union. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

[At 34:26] It's so bad...if you look at a lot of their mid-twentieth century adaptations of popular typefaces for wood...the curves just look like they were cut with a hacksaw.

- ^ Silvertant, Eva [@evasilvertant] (7 November 2022). "Gill Sans Bold (1928) No. 30, by Eric Gill. This type specimen amuses me; some wood-type faces look like they're cut from memory, or cut by a tipsy typecutter! This isn't 'quite' Gill Sans Bold. From 'Wood Letter Specimens' (H. M. Sellers & Co., 1965)" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Gottwald, Dave (6 January 2018). "Typography As Theming in the Ol' West". Themerica. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Gottwald, David. "The Colossal, Stupendous 19th Century Wood Type Explosion!". David Gottwald. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Rob Roy Kelly Obsessions: Wood Type Research". www.rit.edu. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Kelly 1969.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan. "A Treasury of Wood Type Online". Hoefler & Co. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Hoefler, Jonathan. ""Curved, Pointy, and Nervous-Looking Types"". Hoefler & Co. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "The Rob Roy Kelly American Wood Type Collection". School of Design and Creative Technologies, Department of Art and Art History, University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Shields 2022.

- ^ Shields, David (4 December 2018). "Rob Roy Kelly: A bottle of Scotch for two cases of wood type with David Shields". Vimeo. Cooper Union. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Shields, David (26 October 2016). "Muster Hundreds! Towards a people's history of American wood type". YouTube. ATypI. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Shields, David (18 October 2017). "The proliferation of 19th (and 20th) century wood type and its impact on typographic norms, with David Shields". Vimeo. Cooper Union. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Heller, Steven (17 August 2022). "The Daily Heller: The Gospel According to Wood Type's Patron Saint". Print. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Adobe Originals: More than just one collection". Type Network. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Riggs, Tamye. "The Adobe Originals Silver Anniversary Story: Expanding the Originals". Adobe Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Enschedé, Charles (1978). Carter, Harry; Hellinga, Lotte (eds.). Typefoundries in the Netherlands, from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century: a history based mainly on material in the collection of Joh. Enschedé en Zonen at Haarlem (2nd ed.). Haarlem: Stichting Museum Enschedé. p. 33. ISBN 9789070024130.

- Gray, Nicolete (1977). Nineteenth Century Ornamented Typefaces.

- Kelly, Rob Roy (1963). "American Wood Type". Design Quarterly (56): 1–40. doi:10.2307/4047285. JSTOR 4047285.

- Kelly, Rob Roy (1969). American Wood Type, 1828–1900.

- Lewis, John (1962). Printed Ephemera: the changing uses of type and letterforms in English and American printing. Ipswich: W. S. Cowell.

- Mosley, James, ed. (1990). A Specimen of Printing Types & Various Ornaments 1796: Reproduced Together with the Sale Catalogue of the British Letter-Foundry 1797. Printing Historical Society. pp. 5–12. ISBN 9780900003103.

Big types had been cast in sand, using wooden patterns, for some centuries [by 1750] but there is evidence that English typefounders only began to make big letters for posters and other commercial printing towards 1770, when Thomas Cottrell made his 'Proscription or Posting letter of great bulk and dimension' and William Caslon II cast his 'Patagonian' or 'Proscription letters'.

- Mosley, James (1993). Ornamented types: twenty-three alphabets from the foundry of Louis John Poucheé. I.M. Imprimit in association with the St. Bride Printing Library.

- Mosley, James (2001). "Memories of an Apprentice Typefounder". Matrix. 21: 1–13.

- Mosley, James (2003). "Sanspareil Matrices". Matrix. 23: 104–114.

- Schneider, Daniel (2015). Wood Type Archaeology: an inquiry into worker skill in wood printing type manufacture (Thesis). Michigan Technological University. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- Shaw, Paul (April 2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 132–155. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- Shields, David (2022). The Rob Roy Kelly American Wood Type Collection: A History and Catalog. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-2368-7.

- Vervliet, Hendrik D. L.; Carter, Harry, eds. (1972). Type Specimen Facsimiles II. University of Toronto Press. pp. 7–11.

External links

[edit]- Examples on Fonts In Use

- David Shields' list of wood type specimen catalog facsimiles and digital copies

- Ampersand Press collection of French wood type specimens on the Internet Archive

- Woodtyper, a wood type discussion site edited by Nick Sherman

![Condensed Gothic (sans-serif)[c]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/Leavenworth_Sixteen_and_Twelve_Lines_Condensed_Gothic.jpg/112px-Leavenworth_Sixteen_and_Twelve_Lines_Condensed_Gothic.jpg)

![Chromatic colour separation Pointed and Tuscan wood type, Wm. H. Page & Co., 1874 specimen[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Pointed_and_Tuscan_wood_type%2C_Wm._H._Page_%26_Co.%2C_1874_specimen.jpg/134px-Pointed_and_Tuscan_wood_type%2C_Wm._H._Page_%26_Co.%2C_1874_specimen.jpg)