Winston Churchill in politics, 1900–1939

This article has an unclear citation style. (June 2020) |

This article documents the career of Winston Churchill in Parliament from its beginning in 1900 to the start of his term as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in World War II.

Churchill entered Parliament as member for Oldham in 1900 as a Conservative. He changed parties in 1904 after increasing disagreement with the mainstream Conservative policy of protectionist tariffs preferentially favouring trade with the British Empire, joining the Liberals and winning the seat of Manchester North West. His political ascent was rapid; he became, successively, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, President of the Board of Trade, Home Secretary, and First Lord of the Admiralty, all before he was 40 years old.

His career suffered a severe check in 1915, after his support for the failed Dardanelles Campaign during World War I, and the subsequent formation of the first Coalition. Temporarily leaving politics, he served on the Western Front before rejoining the Government after David Lloyd George had replaced H. H. Asquith as prime minister. He served as Minister of Munitions, Secretary of State for War, Secretary of State for Air, and Secretary of State for the Colonies before the downfall of the Coalition in 1922 when he also lost his seat in Parliament.

After contesting two seats unsuccessfully as an independent, he was elected to Epping in 1924 with the backing of local Conservatives, officially rejoining the Conservative Party the following year. He immediately became Chancellor of the Exchequer, retaining the post until the fall of the Conservative government in 1929, and presided over the return of the United Kingdom to the Gold Standard exchange rate system. In opposition after 1929, Churchill became isolated, opposing Indian independence, advocating the unpopular policy of rearmament in the face of a resurgent Germany, and supporting King Edward VIII in the abdication crisis. By 1939, he had been out of Cabinet for ten years, and his career seemed all but over.

Early years in Parliament

[edit]Entry into politics

[edit]

Churchill discussed his political convictions in letters to his mother and made a number of unflattering comments about the Conservative government including:[citation needed]

Were it not for home rule [in Ireland] to which I will never consent—I would enter parliament as a Liberal. As it is—Tory Democracy will have to be the standard under which I shall range myself.

His beliefs were significantly influenced by those of his father, Lord Randolph, after whose early death he wrote:[1]: 62

All my dreams of companionship with him, of entering Parliament at his side and in his support were ended. There remained only for me to pursue his aims and vindicate his memory.

Randolph had been a fervent supporter of Ulster Unionism and had played a major part in formulating the policy of "Tory Democracy", though he had chosen a career in the army for Churchill. After a few years of army life Churchill came to realise that he could not hope to support himself on army pay, and writing remained his main source of income throughout his life. His military career would be valuable for giving him the fame needed to enter politics, however, as he wrote to his mother:[2]: 15–16

A few months in South Africa would earn me the SA medal and in all probability the Company's Star. Thence hot-foot to Egypt—to return with two more decorations in a year or two—and beat my sword into an iron dispatch box.

His first political appearance was at a meeting of the Conservative Primrose League, in Bath in 1897, while at home on leave from the army in India. Having discovered that the Conservative Party needed speakers, as he later commented: "I surveyed the prospect with the eye of an urchin looking through a pastrycook's window".[1]: 21 The speech concerned the benefits to the working man of "Tory Democracy" and was reported in the Morning Post.[3]: 26–27

His first attempt to enter Parliament was unsuccessful when in July 1899 he was defeated in a by-election for the seat of Oldham in Lancashire. The constituency returned two members of parliament, both Conservatives at the previous election. One of them was ill and sought to retire, and Churchill was chosen as the new candidate. However, before the election the second member died so that two new candidates stood against two respected Liberal candidates, at a time when the popularity of the Conservative government was in decline.[3]: 47–49

Churchill looked about for a way to improve his public standing after the defeat. He arranged to travel as a war correspondent to South Africa, fortified by a letter of recommendation to the high commissioner, Alfred Milner, from the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, who had been a friend of his father, and by a promise of a military attachment. His reputation was considerably improved by his war reports published in national newspapers, and by his own military exploits, particularly his capture by and escape from the Boers.[3]: 50–65

Member for Oldham

[edit]Churchill stood again for Oldham in the 1900 general election, known as the "Khaki election" because the Conservative government greatly benefited from its success in the Boer war.[3]: 23–24 This time he came second, pushing one of the Liberal candidates into third place, and was elected. In both of these elections, his campaign expenses were paid for by his cousin the 9th Duke of Marlborough.[4]: 37

Churchill chose not to attend the opening of Parliament in December 1900 and instead embarked on a speaking tour throughout Britain and the United States. With the success of his tour and through his prolific writing in various journals and books, he earned £10,000 for himself in 1899 and 1900 (equivalent to around £500,000 in 2001).[3]: 69–70 Members of Parliament were unpaid and Churchill had inherited almost no money; the income he did inherit from his father's estate, he assigned to his mother in 1903.[4]: 26 He took his seat in Parliament in February 1901.

In Parliament, Churchill became associated with a group of Conservative dissidents led by Lord Hugh Cecil called the Hughligans, a play on words with "hooligans". His first major speech in Parliament was an attack on the proposal of Secretary of State for War St John Broderick to expand the army to six corps, three of which would be free to form an expeditionary force overseas. Churchill had prepared his speech for over six weeks and spoke for an hour without notes. The speech showed his rhetorical powers and was compared by commentators at the time to that of his father's first success—also an attack on a cabinet minister of his own party.[5] Churchill maintained the campaign in and out of Parliament for some time.[nb 1]

In 1902, Churchill revealed some of his views in an interview at the University of Michigan only published six decades later. In the interview, he spoke candidly about his desire for "the ultimate partition of China", as "the Aryan stock is bound to triumph." He also expressed lack of concern for Russian expansion towards China and India, as "Russia has a justifiable ambition to possess a warm water port. It is really embarrassing to think that 100,000,000 people are without one"—an unusual view during the era of the Great Game.[7]

By 1903, he was drawing away from Lord Hugh's views, although they remained friends – Lord Hugh was Churchill's best man in 1908. He also opposed the Liberal Unionist leader Joseph Chamberlain, whose party was in coalition with the Conservatives. Chamberlain proposed extensive tariffs intended to protect Britain's economic dominance. Churchill then and later supported free trade. In this he was supported by Lord Hugh and other Conservatives, including the then Chancellor of the Exchequer C. T. Ritchie. Chamberlain's Tariff Reform movement gained strength splitting the Conservative-Unionist alliance. Churchill's attacks on the Conservatives continued on a number of topics, his dissatisfaction had many causes.[8]: ch 2 His dissatisfaction grew, he made personal attacks on some of the leaders, including Chamberlain, and was reciprocated; Conservative backbenchers staged a walkout once while he was speaking.[3]: 86 and many were personally hostile to him.[5]: 28 His own constituency effectively deselected him, the Conservative Association passing a resolution that he "had forfeited their confidence in him."[9] Oldham was an important cotton-spinning centre whose electorate favoured the Unionist policy of Protectionism, which advocated duties on cheap foreign textiles. He continued to sit for Oldham until the next general election.

Crossing the floor

[edit]Churchill's dissatisfaction continued to grow and, on 31 May 1904 as Parliament resumed following its Whitsun recess, he crossed the floor of the House of Commons, defecting from the Conservatives to sit as a member of the Liberal Party.[3]: 88 His cousin Ivor Guest followed him. Suggested reasons for Churchill's changing sides have included the prospect of a ministerial post and salary,[4]: 27 a desire to eliminate poverty, and concerns for the working class, [nb 2] but the immediately preceding events were the rift with the Conservative Party over trade tariffs.[12] He may simply have been more sympathetic to the Liberals, despite being personally conservative and traditionalist; in 1962 he reportedly told another MP "I'm a Liberal. Always have been."[2]: 24 As a Liberal, he continued to campaign for free trade.[nb 3]

Contemporaries noted that Churchill seemed very like his father, W. S. Blunt writing:

- In mind and manner he is a strange replica of his father, with all his father's suddenness and awareness, and I should say, more than his father's ability.[5]: 40

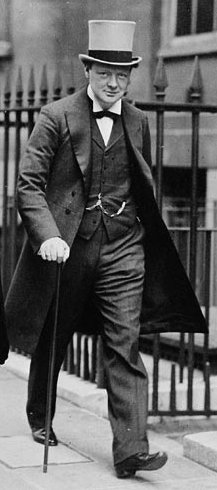

That resemblance went far; Churchill dressed like his father, and the Hughligans have been seen as the recreation of Lord Randolph's Fourth Party.[14]

From 1903 until 1905, Churchill was also engaged in writing Lord Randolph Churchill, a two-volume biography of his father which was published in 1906 and received much critical acclaim.[3]: 102–103 [15] However, filial devotion caused him to soften some of his father's less attractive aspects.[3]: 101 Theodore Roosevelt, who had known Lord Randolph, reviewed the book as "a clever, tactful, and rather cheap and vulgar life of that clever, tactful, and rather cheap and vulgar egotist".[4]: 47 Historians suggest Churchill used the book in part to vindicate his own career and in particular to justify crossing the floor.[4]: 41 [5]: 34–35 Churchill himself later wrote that studying his father's life was a major cause of his disenchantment with the Conservatives.[5]: 40

Growing prominence

[edit]

When the Liberals took office, with Henry Campbell-Bannerman as prime minister, in December 1905, Churchill became Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies.[nb 4] Serving under the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, Churchill dealt with the adoption of constitutions for the defeated Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange River Colony and with the issue of 'Chinese slavery' in South African mines. His first speech after taking office, in which he tried to defend Lord Milner while opposing his policies was a failure. Churchill had prepared it in advance, he had rehearsed it before his private secretary. While the speech reads well, it was not suited to the mood of the House, and the Conservatives proclaimed that Churchill was finished.[17]: 19 [5]: 38–39 It was a failure of his technique of writing his speeches in advance. But he learned from his mistakes. His speech in which he vainly sought Conservative support for the Boer Constitutions was perhaps his strongest yet:

There is a higher authority which we should earnestly desire to obtain. I make no appeal, but I address myself particularly to the Hon. gentlemen opposite, who are long versed in public affairs, and who will not be able all their lives to escape from a heavy South African responsibility. They are the accepted guides of a Party which though a minority in this House, nevertheless embodies nearly half the nation. I will ask them seriously whether they will not pause before they commit themselves to violent or rash denunciation of this great arrangement...with all our majority we can only make it a gift of a Party, they can make it the gift of England.[5]: 42

In the 1906 general election, he won the seat of Manchester North West (carefully selected for him by the party). His electoral expenses were paid for by his uncle Lord Tweedmouth, a senior Liberal.[4]: 3

Churchill had become one of the most prominent members of the Government outside the Cabinet. Indeed, Campbell-Bannerman had proposed his promotion to the Cabinet while Churchill was still Undersecretary, but the King vetoed his appointment.[18]: 181 When Campbell-Bannerman was succeeded by H. H. Asquith in 1908, he was promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. Under the law at the time, a newly appointed cabinet minister was obliged to seek re-election at a by-election. Churchill lost his Manchester seat to the Conservative William Joynson-Hicks. Almost one third of the seat were Jewish and many others were Roman Catholic. The Liberals' failure to repeal the Tories' Aliens Act 1905 (which restricted Jewish immigration) and Churchill's slowness in committing to Home Rule, together with Churchill's concentration on national rather than local issues are given as the reason for his defeat.[19] He was soon elected in another by-election at Dundee constituency.

As President of the Board of Trade he supported David Lloyd George, the newly appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer, in opposing the 1908–1909 naval estimates. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Reginald McKenna proposed six dreadnoughts. Lloyd George, with Churchill's support wanted only four. Eventually the government ordered eight. Churchill gave speeches on this issue, referring to his father's campaign for economy, and circulated open letters to his constituents (again following his father's practice).[5]: 41–42

Also as President of the Board of Trade, Churchill took an active role in bringing about the radical social reforms which have become known as the Liberal reforms. The first of these, passed while Churchill was still Colonial Undersecretary, the Trade Disputes Act 1906 overturned the Taff Vale Case by providing that unions were not liable for damages caused by strike action.[3]: 147

His direct achievements at the Board of Trade were considerable particularly in employment law. He was responsible for the Coal Mines Regulation Act 1908 (8 Edw. 7. c. 57), which provided for an 8-hour day in all mines; the Trade Boards Act 1909, which established the first minimum wage system in Britain, mandating rates for both time- and piece-work for 200,000 workers in several industries (Churchill was able to get Conservative support for this and the Bill "passed without a division."[20]) and the Labour Exchanges Act 1909, setting up offices to help unemployed people find work.[3]: 150–151 As Home Secretary he continued these reforms with the National Insurance Act 1911, providing sickness and unemployment benefits.[3]

As a Cabinet Minister he had three outstanding qualities: he worked hard, he carried his proposals through Cabinet and Parliament, and he carried his department with him. These qualities, the historian, parliamentary clerk, and politician Robert Rhodes James notes, are not as common as they should be.[5]: 43 Churchill himself put his advancement to his submissions to Cabinet, not to his speeches.[21]

Churchill's most important indirect role in these reforms was his assistance in passing the People's Budget and the Parliament Act 1911.[3]: 157–166 The Budget included the introduction of new taxes on the wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. Churchill biographer William Manchester called the People's Budget "a revolutionary concept" because it was the first budget in British history with the expressed intent of redistributing wealth to the British public.[22] When the Budget was discussed in 1909 he did feel some ambiguity over it.[3]: 159 But despite his doubts about its effectiveness, he launched himself into the fight for the budget and accepted the presidency of the Budget League, an organisation set up in response to the opposition's Budget Protest League.[3]: 161

After the budget was sent to the Commons in 1909 and passed, it went to the House of Lords, where it was subsequently vetoed. The Liberals than fought and won two general elections in January and December 1910 to gain a mandate for their reforms. In these campaigns which resulted in the curbing of the Lords' veto by the Parliament Act, Churchill was again to the fore, adding humour in his speeches:

"All civilisation," said Lord Curzon quoting Renan, "is the work of aristocracies." They liked that in Oldham. There was not a duke, not an earl, not a marquis, not a viscount in Oldham who did not think that a compliment had been paid to him. "All civilisation is the work of aristocracies." It would be more true to say "The upkeep of aristocracies has been the hard work of all civilisations."[5]: 38

In 1909 Churchill published a collection of speeches with a foreword under the title Liberalism and the Social Problem.[23] In it he argued for maintaining much of the social order and for gradualism in reform. He wanted to make the existing society work better and more humanely so as to preserve it better. Churchill, it was said, wanted a society where the upper class remained in control, distributing benefits to a grateful and industrious working class.[5]: 44–46 He was then compared with Lloyd George who was seen as Churchill's mentor[24] and from whom Churchill learned much, but who, unlike Churchill, wanted to change some of the fundamental structures of society. Churchill was one of very few Liberals who pressed for the expansion of the House of Lords whether or not the Parliament Act was passed.[3]: 223

Home Secretary

[edit]

In 1910, Churchill was promoted to Home Secretary. His term was marked by three main controversies: a violent Rhondda coalminers' strike and industrial relations issues generally, his responses to the Siege of Sidney Street and the suffragettes agitation.

In 1910, 30,000 Welsh coal miners in the Rhondda Valley began a major strike. Violence against strike breakers threatened in an episode known as the Tonypandy riots. Initially, the chief constable of Glamorgan requested that troops be sent in to help police quell the rioting. Churchill, in collaboration with War minister Richard Haldane allowed them to go as far as Swindon and Cardiff and authorised Nevil Macready, the commanding general, to advance further if he should judge it necessary. Churchill, who had already forbidden the use of forces in another industrial dispute at Newport, did not favour deployment of troops, fearing a repeat of the 1887 Bloody Sunday in Trafalgar Square. In particular, Churchill forbade the use of troops as strike breakers.[5]: 48 There was no massacre—but one coal miner was killed. Churchill considered the military solution to have been effective, and increasingly made use of Army units in disturbances, but to his surprise they did not always show the same restraint and fairness as they had shown at Tonypandy.[25] On 9 November, the Times leader criticised this decision, saying that responsibility for the "renewed rioting late last night...will lie with the Home Secretary [Churchill]" for countermanding the chief constable's request for troops. In spite of this, the rumour persisted that Churchill had ordered troops to attack. Britain's trade unions were outraged against Churchill and never looked at him with favor again.[26][27]

In early January 1911, Churchill arrived at the "Siege of Sidney Street" in London. He gave his own account of the incident in his book Thoughts and Adventures. There is some uncertainty as to whether Churchill attempted to give operational commands. Biographer Roy Jenkins comments that the reason he went was because "he could not resist going to see the fun himself" and that he did not issue commands.[3]: 194 A famous photograph from the time shows Churchill at the scene, peering around a corner to view the gun battle between cornered anarchists and Scots Guards. His role and presence attracted much criticism. The building under siege caught fire, and Churchill supported the decision to deny the fire brigade access, forcing the criminals to choose surrender or death. After an inquest, Arthur Balfour remarked, "He [Churchill] and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing but what was the Right Honourable gentleman doing?"[3]: 195 The significance was that the whole highly publicised affair increased Churchill's already incipient reputation for being a frenetic and far-from-calm Home Secretary.[3]

While still at the Board of Trade in 1909, Churchill was accosted with a whip by suffragette Theresa Garnett.[3]: 186 [28]: 237 Churchill's proposed solution was a referendum on the issue but this found no favour with Asquith and women's suffrage remained unresolved until after World War I.[28]: 186

Prison reformer

[edit]The British penal system underwent a transition from harsh punishment to reform, education, and training for post-prison livelihoods. The reforms were controversial and contested; they were championed by Winston Churchill as Home Secretary.[29] He first achieved fame as a prisoner in the Boer war in 1899. He escaped after 28 days and the media, and his own book, made him a national hero overnight.[30] He later wrote, "I certainly hated my captivity more than I have ever hated any other in my whole life....Looking back on those days I've always felt the keenest pity for prisoners and captives."[31] As Home Secretary he was in charge of the nation's penal system. Biographer Paul Addison says. "More than any other Home Secretary of the 20th century, Churchill was the prisoner's friend. He arrived at the Home Office with the firm conviction that the penal system was excessively harsh". He worked to reduce the number sent to prison in the first place, shorten their terms, and make life in prison more tolerable, and rehabilitation more likely.[31] His reforms were not politically popular, but they had a major long-term impact on the British penal system.[32][33]

First Lord of the Admiralty

[edit]

In 1911, Churchill was transferred to the office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, a post he held into World War I. This was the year of the Agadir Crisis, with which Churchill opens The World Crisis, his account of World War One. His first major act was to replace all but one of the Sea Lords, the senior naval officers who administered the Admiralty. With the aid of the new First Sea Lord Sir Francis Bridgeman he created a war staff,[34]: ch IV gave impetus to reform efforts, including development of naval aviation (he undertook flying lessons himself),[35] the use of the 15" gun as the main armament of battleships, the development of the fast battleship (which found shape in the Queen Elizabeth class) and of the 6" gunned light cruiser (which found shape in the Arethusa class) concepts,[34]: ch 4, 6 and the switch from coal to oil in the Royal Navy, a massive engineering task, which depended on securing oil supplies in Mesopotamia.[36] In 1912, in response to the German Naval Law of that year, Churchill brought forward Naval Estimates based on a principle of building two British battleships to every one German, which became known as 'two keels to one."

Churchill was influenced in these reforms by the (then-retired) Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher, who had been for many years a driving force for innovation in the Royal Navy. The two men had become very close at Biarritz in April 1907. In 1909, Fisher had been First Sea Lord and on the opposite side to Churchill in the debates over the Naval Estimates. However this was a temporary tension, and the friendship persisted. Fisher remained in close touch with naval affairs after his retirement from the Admiralty in January 1910, and Churchill consulted him almost instantly upon taking up the office of First Lord.[37]: 431–32 Many of the ideas Churchill took up, like oil propulsion and ever-bigger battleships with ever-bigger guns, were causes Fisher backed.[37]: 435–37

In 1912 the Liberal Government, since the elections in 1910 dependent upon Irish National support, introduced what became the Home Rule Act 1914. The Unionists (the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists had united in 1911) bitterly opposed this, demanding that Ulster be excluded from the Home Rule Parliament. Privately Churchill sought a compromise.[5]: 57 Publicly (and particularly after Sir Edward Carson's Ulster Covenant by which over half a million men pledged to oppose Home Rule by 'all means which shall be found necessary' and the formation of the Ulster Volunteers), he campaigned for the Bill by speeches in Ulster and England and open letters.[5]: 58 In a 1912 speech on the floor of the House of Commons, Winston spoke of Irish in favourable terms as an "ancient people, famous in history, influential all over the English speaking world, whose blood has been shed on our battlefields, whose martial qualities have adorned our ensign...".[38] His support for the Home Rule Bill caused anger among the Unionists because Lord Randolph had been the champion of Ulster against Parnell's original Home Rule campaign.

As the crisis deepened, with the Ulster Volunteers drilling openly, Churchill arranged for a Royal Naval battleship squadron to cruise off Belfast[39]: 148 without first raising the issue in Cabinet. Asquith cancelled the move two days later.[5]: 63 The cancellation is not mentioned in The Gathering Storm. It appeared to the Unionist leaders that Churchill and his friend War Secretary John Seely were seeking to provoke the Unionists into some outward act that would allow Ulster to be placed under some form of military rule.[40][page needed] The attempts to move troops led to the Curragh Incident, Seely's resignation, a back down by the Government, and negotiations brokered by King George V.[41]

This incident revealed for the first time that Churchill was not prepared to negotiate under pressure, that while he would compromise behind the scenes and be magnanimous in victory, when confronted by a foe he stood his ground. This was an attitude he maintained through his career As he wrote in My Early Life p. 327[1]

I have always urged fighting wars and other contentions with might and main till overwhelming victory and then extending the hand of friendship to the vanquished. Thus I have always been against the Pacifists during the quarrel and the Jingoist at its close...I thought we should have conquered the Irish then given them Home Rule...and that after smashing the General Strike we should have met the grievances of the miners.

World War I

[edit]The start of the war

[edit]On 31 July 1914, Churchill ordered the seizure of the two Turkish battleships (Reşadiye and Sultan Osman I) then under construction in Britain. Although this decision was probably a wise one,[5]: 74 the way the order was carried out was not. The ships were boarded without negotiations with Turkey or compensation, and the British placed guards on one of the battleships to prevent Turkish sailors from boarding. The order probably helped propel Turkey into alliance with Germany. (Two German warships arriving in Turkey, the Goeben and the Breslau, were portrayed as replacements.) Churchill later defended himself referring to the negotiations that the Germans were starting with the Young Turks.[34]: 169 But Britain was also negotiating with Turkey at the same time and on 18 August Turkey declared neutrality.[42]

Admiral Beatty wrote to his wife that Churchill should either give the Admiralty his full attention or leave it alone, but his "flying about and putting his finger to pies which do not concern him is bound to lead to disaster". Churchill believed that he had "special knowledge" and an ability to improvise solutions, but others saw it as megalomania.[43]

Antwerp

[edit]In September 1914, with the Allies advancing after their victory at the Marne, Joffre suggested that the British land a force at Dunkirk to threaten the German right flank; at Kitchener's suggestion Churchill took over the mixed force of marines and yeomanry.[44] Churchill was soon making frequent trips to Dunkirk, where he had set up a RNAS squadron and some units equipped with Rolls Royces which had been turned into ad hoc armoured cars. He arranged for 70 London buses to be used for extra mobility.[45]

Churchill was on his way to Dunkirk on the night of 2 October when his train was halted and he was taken back to London for a meeting with Kitchener, Sir Edward Grey (Foreign Secretary), Prince Louis of Battenberg (First Sea Lord) and Sir William Tyrrell, Grey's secretary (Asquith was away making a recruiting speech in Cardiff). They warned that King Albert of the Belgians planned to evacuate Antwerp.[45] Churchill later claimed that it had been a collective decision that he should go to Antwerp but Sir Edward Grey later wrote, more plausibly in historian John Charmley's view, that it was very much Churchill's idea.[43]

Churchill arrived in Antwerp around 3pm on 3 October. He set up in the best hotel in Antwerp with Admiral Oliver (Chief of Naval Intelligence) as his secretary, and spent the afternoon touring the defences under shellfire.[45] He wore undress Trinity House uniform.[44] Churchill soon came to an arrangement with the Belgians that they would hold out provided the British sent substantial reinforcements. He asked for the two naval brigades, "minus recruits".[43] On 4 October Churchill offered to resign from the Cabinet and take personal command of the newly formed Royal Naval Division, which would incorporate the Marine and Naval Brigades.[45][44][43] Kitchener wanted to commit an Anglo-French expeditionary force to secure Antwerp,[34]: 320 and annotated the telegram to say that he was willing to appoint Churchill a temporary lieutenant-general, but Asquith thought it unwise and recorded that Churchill's suggestion was met with a "Homeric laugh" by the Cabinet. Instead Churchill was recalled to London.[45][44][43] The Royal Marine brigade arrived on 4 October. The 1st and 2nd Naval Brigades were then sent. They consisted largely of untrained reservists.[44] General Rawlinson arrived on 7 October to take charge.[45] Churchill returned to London on 7 October as something of a hero, but this changed when Antwerp fell on 10 October. Around 2500 of Churchill's largely untrained troops were killed, taken prisoner or interned in the neutral Netherlands.[45][44][43]

Churchill attracted ridicule.[44] He was strongly criticised by The Morning Post ("a costly blunder for which Mr W. Churchill must be held responsible") while Admiral Beatty wrote to his wife that Churchill had been "a darned fool" and "mad". Asquith wrote to Venetia Stanley likening Churchill to a tiger which has "tasted blood" and who was hinting that he wanted other opportunities for a major field command, and that he preferred military glory to political success. By 13 October Asquith was writing of "the wicked folly of it all" and that Churchill had led "sheep to the shambles".[43] He faced criticism for his poor judgment from his wife Clementine (he missed the birth of his daughter Sarah), and in his later writing conceded that he might have done things differently.[45] The Dunkirk force was also wound up after others, including Asquith, grew irritated about it.[44]

Modern historians tend to take a kinder view of Churchill's actions at Antwerp. He had asked for the brigades minus recruits, and it had been Kitchener who insisted on retaining territorials in the UK to defend the East Coast against possible German invasion. Only 57 men were actually killed.[46] In The World Crisis Churchill claimed he had prolonged Belgian surrender by a few days and occupied five German divisions.[34]: 323 In fact it had been a week and enabled Calais and Dunkirk to be secured. Rhodes James believes that Antwerp was "substantially to Churchill’s credit".[44] However, at the time he had thought that holding Antwerp would help the Allied advance north; the claim that it helped hold Calais and Dunkirk when the German advance resumed is hindsight.[43] The more damaging attack, made inside and outside the Cabinet, was that Churchill was seeking publicity instead of running his department.[47]: 293

Replacement of Battenberg

[edit]Churchill was also unpopular within the Navy itself for the replacement of Sir George Callaghan by Sir John Jellicoe as commander of the Grand Fleet and for bowing to public pressure and dismissing Prince Louis of Battenberg as First Sea Lord, although he was one of the last members of the government to concede that Battenberg had to be replaced.[48]: 82–88

Early development of the tank

[edit]Churchill played an important role in Britain's development of the tank,[nb 5] which he funded from the Navy budget without involving the War Office. In February 1915 he established the Landship Committee, which oversaw the design and construction of two prototypes, and during his period out of office he remained in close contact with the developers. By September 1916 the tank had been officially adopted by the Army and used in battle. On his appointment as Minister of Munitions in July 1917, Churchill assumed responsibility for the further development and production of tanks, and encouraged joint projects with the US.

Dardanelles Campaign

[edit]In early 1915, Churchill campaigned for an amphibious assault on the Belgian coast in 1914, which was opposed by Lord Kitchener at the War Office and Sir John French commanding the British Expeditionary Force.[49][page needed] Churchill then became one of the political and military engineers of the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign.[50]

In 1911, Churchill had written that "it is no longer possible to force the Dardanelles".[5]: 82 Nonetheless, Churchill and others in the Admiralty, including Admiral Oliver, the Chief of the Naval Staff, were impressed by the German bombardment of Belgian fortresses in the Battle of Liège at the start of the war. As early as August 1914, he had ordered an appreciation of "a plan for the seizure of the Gallipoli peninsula, by a Greek army of adequate strength, with a view to admitting a British fleet to the Sea of Marmara." This was some three months before Turkey was at war and more than two years before Greece entered the war. Although later in August Greece did offer to attack Turkey, the offer was not accepted by Britain due to complaints from its ally Russia, and was withdrawn before Turkey entered the war in October.[51]: 10

Churchill pressed the issue at successive meetings of the War Council in 1914. After an exchange of telegrams with Admiral Sackville Carden, the Commander in the Aegean, he tabled his plan for forcing the Straits by naval bombardment at a further meeting of the Council in January 1915. He had not sought the view of the Naval Staff, and those senior naval officers with whom he had discussed the plan were dubious or opposed to the scheme.[5]: 85 The concept was flawed. The first attacks by the Navy in February 1915 were successful but were not pressed home (partly because of bad weather) and no troops were available to secure the gains made. Instead marines blew up the outer forts, which were reoccupied and rebuilt when the marines left.[51]: 163 The War Council had discussed using the 29th Division (then in Britain) and the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (then in Egypt) but no decision had been made when the naval attacks began.[5]: 89 At the time, Churchill claimed the navy could do the job alone and the troops would be needed—if at all—as an occupying force once the Straits were forced.[5]: 90

Carden's attack was slowed because the inner forts were concealed from the ships and few aircraft were available for spotting purposes (the seaplane tender HMS Ark Royal which supported the fleet carried just five seaplanes of an older design lacking sufficient range). Carden asked to discontinue the attack until there were more available.

Churchill refused, requiring the attack to continue,[52] and Carden planned to continue but then collapsed from a rupturing ulcer. His second in command, Admiral John de Robeck took over and pressed a further attack on 18 March, but this failed when the trawler minesweepers crewed by Royal Naval Volunteer Reserves (i.e. civilian seamen) came under attack and then the battleships ran into a mine field (three were sunk). De Robeck did not repeat the attacks, later giving his reason as concerns over what would happen if his ships succeeded in clearing a way through the strait, but then became trapped in the Sea of Marmora without any troops to occupy captured territory.[48]: 252 Churchill had anticipated the loss of ships: the battleships were mainly chosen because they were obsolete and unfit to face modern German ships, and he believed that the attack should have continued.[34]: vol.2 670–690 Commodore Roger Keyes (Carden's chief of staff) believed that with destroyers fitted for minesweeping, and with naval personnel manning the trawlers, the mines could have been removed. These improvements were carried out, but never tried against the defences. It was also reported at the time that the defences were short of ammunition, and now seems likely that at least some of guns, particularly the largest, would have been forced to cease firing the following day.[53]

The landings by the ANZAC, the 29th and Royal Naval divisions, and a French division were delayed until 25 April because of lack of preparations, by which time the Turks had deployed six divisions and created barbed wire and trench defences on likely landing sites. The troops landed against heavy resistance, but never managed to advance far from the initial bridgeheads, nor to capture the forts on the European side of the Dardanelles.

Churchill was widely blamed for the fiasco. Some historians have argued that he was right in saying that had the naval attacks been pressed the Turks, short of ammunition and low in morale would have had to abandon the forts and the Fleet could have occupied the Sea of Marmora and with it Constantinople.[51]: 165 But it is even more likely that had the Fleet been properly equipped with spotter planes and destroyer minesweepers, the attack on 18 March would have been successful. It is almost certain that a Fleet so equipped and supported by the four divisions made available in April would have cleared the Strait with almost no loss. As the minister responsible, Churchill was the one who did not provide the resources needed.[5]: 97–99 Clement Attlee, who served in the army at Gallipoli, described the campaign as "an immortal gamble that did not come off... Sir Winston had the one strategic idea in the war. He did not believe in throwing away masses of people to be massacred".[48]: 260

The Asquith Coalition, the Dardanelles Committee

[edit]The Liberal government was weakened by the failure of the naval attacks and the first landings in Gallipoli, by the failure of the offensive at Neuve Chapelle, and by the Shell Crisis. The Cabinet was bickering and some members plotted against others. Churchill himself aimed to replace Sir Edward Grey as Foreign Secretary with Balfour.[47]: 304 [nb 6] The historian Stephen Koss has argued that Churchill himself created the Shell Crisis. He states that during a visit to BEF Headquarters on 8 May he arranged with Colonel Charles à Court Repington, the Times correspondent there to publish the reports of the lack of shells.[54] James discounts this argument.[5]: 184 On 15 May Fisher resigned as First Sea Lord. He presented the Cabinet with a list of demands; if these were satisfied he would return to office. The first of these was that Churchill would be dismissed from Cabinet altogether. Fisher's demands were extreme, the King saying that Fisher should be hung from the yardarm,[55] but his resignation precipitated a Cabinet crisis.[56]

Prime Minister Asquith formed an all-party coalition government. The Conservatives demanded Churchill's demotion as the price for entry.[3]: 282–288 He had little support in Cabinet or in the Liberal Party as a whole. Many thought the same as Lloyd George: that Churchill's ambition had led him to override his professional advisers and his record was a succession of grisly failures.[47]: 309 Others, including Mrs Asquith, blamed him for breaking the Cabinet and forcing the Coalition.[5]: 103–04 However Sir Max Aitken interceded unsuccessfully with his close friend the Conservative Leader Bonar Law and later wrote of Churchill:

His attitude from August 1914 was a noble one, too noble to be wise. He cared for the success of the British aims, especially insofar as they could be achieved by the Admiralty, and for nothing else. His passion for this aim was pure, self-devoted, and all-devouring. He failed to remember he was a politician.[57]

Churchill was demoted to the sinecure of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and became a member of the newly formed Dardanelles Committee. Churchill blamed Asquith for the demotion,[58] but in fact Asquith and Lloyd George attempted to make Churchill Colonial Secretary.[47]: 309 [nb 7]

In June and again in July, with Kitchener's support he argued for increased forces to be sent to Gallipoli. This led to the despatch of the 2nd Australian Division and the IX Corps to Gallipoli and to the landing at Suvla Bay. The attacks on Churchill redoubled when this landing failed. The Committee appointed General Sir Charles Monro as Commander. He advised evacuation. Churchill bitterly opposed this.[34]: ch. XXXIII The Committee despatched Kitchener to report. He too advised evacuation. Before this took place, the Dardanelles Committee was replaced by a War Committee on 11 November. Churchill was not appointed to this committee. On 15 November, Churchill resigned from his post, feeling his energies were not being used.[3]: 287

During Churchill's time on the Dardanelles Committee he was the sole Liberal supporter of Lloyd George's campaign for conscription. This served to separate him further from the majority of the Liberal Party without healing his breach with the Conservatives, though many of them supported conscription.[47]: 326–29

Upon resigning he rejoined the army, though remaining an MP, and served for several months on the Western Front as commander of the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. During this period, his second-in-command was a young Archibald Sinclair who later led the Liberal Party. Although Churchill did spend some time behind the front, visiting leaders such as Field Marshal Sir John French, Churchill led his battalion into the trenches on 27 January 1916.[3]: 301 In March, Churchill returned to Britain after he had become restless in France and wished to speak again in the House of Commons.[3]: 309 Sir Edward Carson encouraged him to do so.[59]

Return to power

[edit]When he returned to Parliament in summer 1916 Churchill sat on the opposition benches. The opposition at this time was largely dissatisfied Conservatives who were not in the Coalition and was headed by Carson. This changed in December 1916, when Asquith resigned as prime minister being replaced by Lloyd George.[60][incomplete short citation] From then on the opposition was largely the Liberal supporters of Asquith. Churchill was a member of neither group.[5]: 114–16 [61]: 125–29 He was mainly occupied in giving evidence before the Dardanelles Commission, though at Balfour's request he wrote a semi-official statement on the Battle of Jutland.[5]: 116

In July 1917, Churchill was appointed Minister of Munitions. For some months Lloyd George had feared that Churchill might challenge his leadership,[47]: 407 and after a masterly speech by Churchill in a secret session of the Commons on 10 May, Lloyd George approached him seeking his assistance.[61]: 130 The Conservatives and The Times objected to Lloyd George's first proposal—that Churchill be appointed to head the Air Board. Lloyd George then asked Beaverbrook to obtain Bonar Law's agreement to Churchill's appointment (which Lloyd George had already determined upon) to the Ministry of Munitions.[61]: 311 Bonar Law said correctly "Lloyd George's throne will shake." Churchill's own account mentions the important part Freddie Guest (then chief Coalition Liberal whip) played in this but does not disclose that Guest was Churchill's cousin.[34]: 1112 This episode, with its behind-the-scenes negotiations, shows how unpopular Churchill remained at this stage. As Minister, Churchill reorganised the department, arbitrated between the various services' demands for weapons, and repeated his advocacy for tanks,[62] but most of his work was administering an already functioning department. He was a "competent, energetic, and efficient" minister.[5]: 118

Post-war coalition

[edit]War and Air Secretary

[edit]In January 1919, after the 1918 Coupon election, Churchill became Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. He was not a member of the War Cabinet, which continued until November 1919.[47]: 478–79 Churchill had pressed for appointment as Minister of Defence, combining all three service departments and the Ministry of Munitions (now renamed the Ministry of Supply and with a seat in Cabinet). He was unsuccessful.

His first challenge was demobilisation. He inherited a scheme whereby those men required most for industry would be demobilised first. In practice this meant that those who had served in the forces the shortest were being released from the forces first. Ex-servicemen rioted, at one time burning Luton Town Hall.[63] Churchill scrapped the system, instead releasing those who had served longest first.[5]: 130–32 The soldiers' unrest was but one domestic problem: there were strikes and riots in Glasgow, and a proposed national miners strike. Churchill suggested using four divisions of the Rhine Army as strikebreakers.[5]

He was the main architect of the Ten Year Rule, a principle that allowed the Treasury to dominate and control strategic, foreign, and financial policies under the assumption that "there would be no great European war for the next five or ten years".[64] He substantially reduced the RAF—so that it would have four Home and eighteen Imperial squadrons, and he rejected proposals for government support of civil aviation. Liddell Hart commented: "He was anxious to make a fresh start in current political affairs, and the best chance lay in the post-war retrenchment of expenditure."[65]

A major preoccupation of his tenure in the War Office was the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. British forces were already in Russia, at Murmansk, in Siberia, and guarding the Baku railway before Churchill took charge at the War Office. The Cabinet was divided, without a clear policy. While Lloyd George proposed negotiations between all the Russian groups, which led to US President Woodrow Wilson's abortive Prinkipo Plan, Red Army attacks on the British positions led the Cabinet to approve 'forward defence".[5]: 137

Churchill was a staunch advocate of foreign intervention, declaring that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".[66] He secured, from a divided and loosely organised Cabinet,[5]: 143–150 [47]: 495–519 intensification and prolongation of the British involvement beyond the wishes of any major group in Parliament or the nation—and in the face of the bitter hostility of the Labour Party. On 14 January 1919 Churchill circulated a Most urgent and secret memorandum to all commanders of British forces asking whether their forces would serve overseas and particularly in Russia, whether they would serve as strikebreakers and the soldiers' attitude to trade unions. A copy was leaked to and published in the Daily Herald.[5]: 139 In February he attempted to get American and then general Allied support for protracted large-scale intervention. In April he pushed for an offensive, rather than a defensive role for the North Russia force. Claiming the scheme was that of General Ironside and that it was essential for a subsequent evacuation, he wanted the force to link up with Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak's forces to the east.[47]: 502 In May after failing to get Cabinet approval to expand the British-Slavo Legion, he decided this was a purely War Office decision, expanded the Legion, and reported this to the Cabinet, which merely 'noted' the matter.[5]: 144 In July, when Kolchak's force was retreating rapidly, he told the cabinet that a White defeat would allow the Bolsheviks to threaten Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia.[5]: 152 From then until the final evacuation, Churchill continued to argue for support for the White forces. In 1920, after the last British forces had been withdrawn, Churchill was instrumental in having arms sent to the Poles when they invaded Ukraine.

Churchill's actions in supporting the White forces led to a break with Lloyd George which was never completely healed,[47]: 502–504 [61]: 180–83 : 180–83 criticism by the Press[61]: 165 and further distrust from Labour.[5]: 158–59

Churchill was responsible for establishing both the Auxiliary Division and the Black and Tans during the Irish War of Independence. He defended their activities, saying they enjoyed the same freedom as police in Chicago or New York in dealing with armed gangs. He initially advocated the military defeat of the IRA and its supporters. By summer 1921, however, as the Colonial Secretary he was pressing for negotiations. His desired negotiating position was to offer a measure of Irish self-government from a position of strength: he "wished to couple a tremendous onslaught with the fairest offer."[67]

In 1920, as Secretary of State for War and Air, Churchill was responsible for quelling rebellions in British Somaliland and the uprising of Kurds and Arabs in British-occupied Mesopotamia. In each case the rebellions were crushed by co-ordinated air force and army operations.[68] Churchill told the Commons that whereas an army campaign in Somalia would have cost £6,000,000 the air force expedition had cost £70,000. It had involved 6 Airco DH9 bombers and a total of less than 250 aircrew.[69]: 218

Colonial Secretary

[edit]Churchill became Secretary of State for the Colonies on 13 February 1921 (until 19 October 1922) and was a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which established the Irish Free State, having been involved in the lengthy negotiations of the treaty. To protect British maritime interests, he caused the agreement to include three Treaty Ports (Queenstown (Cobh), Berehaven, and Lough Swilly), which could be used as Atlantic bases by the Royal Navy.[3]: 361–365 (The bases were ceded to Ireland in 1938, under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement.) The Irish Civil War broke out after the signing of the Treaty, Churchill supported the government of the Free State with arms and ordered the British forces still in Ireland to assist the Irish National Army against the Republican Army.[nb 8][5]: 170–172

Churchill's other main concern while Colonial Secretary was the Middle East. He wanted Egypt (then administered by the Foreign Office) to be brought under his department's control.[5]: 174 He was faced with continuing riots and communal violence in those parts of the former Ottoman Empire that British forces occupied after World War I. Most of these riots were against the British occupation. Churchill did not want to give the complete independence that some of the Arabs had been promised. Rather, his aims were to reduce the British forces in the region and to ensure that British interests, particularly in the air route to India and the oil fields, were protected. The local population was a less important issue.[nb 9]

After setting up a Middle Eastern Department within the Colonial Office, Churchill convened a conference in Cairo in March 1921, attended by T. E. Lawrence, Gertrude Bell, Sir Hugh Trenchard, Sir John Salmond, and Sir Percy Cox. No Arabs were invited to the conference.[70]

The method recommended by the Conference and chosen by Churchill, summarised by Sir Henry Wilson as 'hot air, aeroplanes and Arabs',[71] was the creation of the Kingdom of Iraq with Lawrence's friend Faisal as King, and the Emirate of Transjordan with Faisal's brother Abdullah as Emir. The boundaries of the two countries were joined in what is sometimes known as Winston's Hiccup. This was intentionally designed to ensure that the air route to India passed over the areas controlled by or friendly to Britain.

Churchill's creation of Iraq from three the Ottoman Vilayets of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul has been criticised as making an artificial state which inevitably would break down.[72] He has also been criticised for advocating the use of gas as a weapon against Arab and Kurdish 'insurgents'. His defenders say that what he intended was the use of generally non-lethal (tear) gas,[73] but those gases were known to kill children and the ill.[74] His policy was to control Iraq with the minimum expenses, so he refused to authorise projects such as a hospital in Iraq.[69]: 239

With regard to Palestine, Churchill implemented a pro-Zionist policy, with the goal of creating a Jewish Homeland at the expense of the indigenous Palestinians. The in 1921, the General Officer Commanding (GOC), General Walter Congreve issued a circular which stated that, while the British Army remained apolitical, it opposed the Zionist agenda, which it called "the grasping policy of the Zionist extremists," and noted that the Palestinians "hitherto appeared to the disinterested observer to have been the victims of an unjust policy forced upon them by the British Government."[75] Churchill's response was to remove control of Palestine's defence from the military, placing it under the Colonial Office, and forming a "Palestine Gendarmerie", recruited from the notorious Black and Tans to police the territory.[76]

Second crossing of the floor

[edit]Anyone can rat, but it takes a certain ingenuity to re-rat.

— Churchill, after rejoining the Conservatives[77]

In October 1922, Churchill underwent an operation to remove his appendix. While he was still in hospital, Lloyd George resigned as prime minister with a general election to be held on 15 November. Churchill was not sufficiently well to travel to his constituency in Dundee until 11 November, causing him great difficulties campaigning. Once there he was still not sufficiently well to stand to address an audience, but had to address meetings where he was heckled and unable to finish speaking.[78] Clementine travelled to the constituency earlier with other friends, but generally the campaign was poorly managed in Churchill's absence.

The constituency had a significantly working-class composition, so that his principal opponents were a candidate for the steadily rising Labour Party, E. D. Morel, and a local prohibitionist, Edwin Scrymgeour, who had stood unsuccessfully in the constituency many times, but steadily increasing his vote each time. The Dundee constituency returned two members, so Scrymgeour and Morel worked in partnership, each lending his factional support to the other. Churchill was partnered by another National Liberal, but they were opposed by an Asquithian Liberal candidate following the split in the party. The result was that Scrymgeour and Morel won, with Churchill relegated to fourth place behind his running mate.[3]: 370–375 Churchill quipped later that he left Dundee "without an office, without a seat, without a party, and without an appendix".[79] The result of the general election was the first non-coalition Conservative government since 1900. The Liberal Party never recovered the position in politics which it had once enjoyed.

Churchill stood for the Liberals again in the 1923 general election, losing in Leicester, but over the next few months he moved towards the Conservative Party in all but name. His first electoral contest as an independent candidate, fought under the label of "Independent Anti-Socialist", was a narrow loss in a by-election in the Westminster Abbey constituency—his third electoral defeat in fewer than two years. However, he stood for election yet again several months later in the general election of 1924, again as an independent candidate, this time under the label of "Constitutionalist" although with Conservative backing, and was finally elected to represent Epping. The following year, he formally rejoined the Conservative Party, commenting wryly that "Anyone can rat, but it takes a certain ingenuity to re-rat."[77]

Chancellor of the Exchequer

[edit]Churchill was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924 under Stanley Baldwin during which Britain returned to the gold standard, this resulted in deflation, unemployment, and was a catalyst to the miners' strike that led to the General Strike of 1926.[80] His party's decision, announced in the 1924 budget, came after long discussions and further consultation with treasury officials, various economists, and the board of the Bank of England. Churchill was very sceptical about the benefits of returning to the gold standard, and widely questioned the almost unanimous advice he was receiving that it was necessary. The governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman, said that 'there was no alternative to a return to gold'. The permanent secretary to the treasury, Sir Otto Niemeyer said that not to do so would show Britain had never 'meant business' about the gold standard, and that 'our nerve had failed'. The parliamentary joint select committee on Currency and Banking under its chairman Lord Bradbury (former permanent secretary to the treasury) supported a return, as did the Labour shadow chancellor, Snowden.[3]: 398–399

Churchill held a dinner at which the principal opponents of a return, economist John Maynard Keynes and former chancellor and chairman of the Midland Bank Reginald McKenna, were encouraged to argue out their case with Niemeyer and Bradbury. The dinner continued into the early hours of the morning but, in the end, Keynes's academic arguments proved unconvincing, and McKenna conceded that Churchill had little political choice except to return to gold.[3]: 400 This decision later prompted Keynes to write The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, arguing that the return to the gold standard at the pre-war parity in 1925 (£1=$4.86) would lead to a world depression. The pamphlet did not criticise the decision to return to the gold standard per se. The decision was generally popular and seen as 'sound economics' although it was opposed by Lord Beaverbrook and the Federation of British Industries.[5]: 207

Churchill later regarded this as the greatest mistake of his life; in discussions with McKenna, he acknowledged that the return to the gold standard and the resulting 'dear money' policy was economically bad. In those discussions, he maintained the policy as fundamentally political — a return to the pre-war conditions in which he believed.[5]: 206 Writing about the events in his biography of Churchill, Roy Jenkins argued that, although Churchill had challenged the proposal to return to the gold standard in the face of almost unanimous political and institutional demand, he had possibly been the only person who could have prevented the enactment of the return to the gold standard legislation at this late stage and its consequences, so ultimate responsibility remained with him for the decision.[3]: 401

The return to the pre-war exchange rate and to the gold standard depressed industries, the most affected being coal mining. Already suffering from declining output as shipping switched to oil, and basic British industries like cotton came under more competition in export markets, the return to the pre-war exchange was estimated to add up to ten per cent in costs to the industry. In July 1925 a commission of inquiry reported generally favouring the miners', rather than the mine owners' position.[3]: 405 Attached to the report was a memorandum from Sir Josiah Stamp stating that the increased difficulties in the coal industry could be entirely explained by the "immediate and necessary effects of the return to gold".[3]: 391–417 Baldwin, with Churchill's support, proposed a subsidy to the industry while a royal commission prepared a further report.[citation needed]

During the General Strike of 1926, Churchill edited the British Gazette, the government's anti-strike propaganda newspaper.[81] After the strike ended, he acted as an intermediary between striking miners and their employers. He later called for the introduction of a legally binding minimum wage.[82]

When Churchill visited Rome in January 1927, he controversially claimed that the fascism of Mussolini had "rendered a service to the whole world", showing, as it had, "a way to combat subversive forces" – that is, he considered Mussolini's regime to be a bulwark against the perceived threat of Communist revolution. At one point, Churchill went as far as to call Mussolini the "Roman genius... the greatest lawgiver among men".[83]

It was not only the return to the gold standard that later economists, as well as those at the time, criticised in Churchill's time at the treasury. Rather it was his budget measures which, even given the consensus at the time that the budgets should be balanced, were attacked as assisting the generally prosperous rentier banking and salaried classes (to which Churchill and his associates generally belonged) at the expense of manufacturers and exporters which were known then to be suffering from imports and from competition in traditional export markets.[84] However, his 1925 budget was well received by the public and enhanced Churchill's prestige.[85] Churchill had served in two of the four Great Offices of State and several other positions. No one had more experience in government, and he could expect another high office in the next Conservative ministry.[86]

Political isolation

[edit]

The Conservative government was defeated in the 1929 General Election. Churchill did not seek election to the Conservative Business Committee, the official leadership of the Conservative MPs. Over the next two years, Churchill became estranged from the Conservative leadership over the issues of protective tariffs and the Indian Home Rule movement, which he bitterly opposed. He further distanced himself from the party as a whole by his political views and by his friendships with press barons, financiers, and people whose characters were seen as dubious. When Ramsay MacDonald formed the National Government in 1931, Churchill was not invited to join the Cabinet. He was at the low point in his career, in a period known as "the wilderness years".[87]

He spent much of the next few years concentrating on his writing, including Marlborough: His Life and Times—a biography of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough—and A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (though the latter was not published until well after World War II).[87] Churchill's depiction of Marlborough in Marlborough: His Life and Times had shown close parallels to his own stand against appeasement. Both were war leaders advocating firm policies, but surrounded by an attacking public and hostile politicians.[4]: 402 [5]: 395–400 In doing so they echo public comments at the time. The Daily Express referred to Churchill's speech in October 1938 against the Munich agreement as "an alarmist oration by a man whose mind is soaked in the conquests of Marlborough".

Though badly hurt when he was struck by a car in New York City on a North American speaking tour, he wrote a profitable article about the experience. He wrote many other articles, collections of speeches, and several books—some such as his Great Contemporaries of lasting worth. He supported himself largely by his writing and was one of the best paid writers of his time.[87]

Nevertheless, he was still in financial difficulties, having lost most of his American investments in the Wall Street Crash. He was criticised for holidaying in the Riviera and America as the guest of such people as Beaverbrook and William Randolph Hearst, and for drinking and gambling with people such as Brendan Bracken and, until his early death, Lord Birkenhead.[4]: 31–36 These attacks were not new; in 1923 Churchill had brought a successful libel action against Lord Alfred Douglas who had accused Churchill of giving a deliberately false account of the Battle of Jutland at the request of Sir Ernest Cassel. Douglas was sentenced to imprisonment for six months.[3]

His political views, set forth in his 1930 Romanes Election and published as Parliamentary Government and the Economic Problem (republished in 1932 in his collection of essays "Thoughts and Adventures") involved abandoning universal suffrage, a return to a property franchise, proportional representation for the major cities, and an economic 'sub-parliament'.[88]

Indian independence

[edit]During the first half of the 1930s, outspoken opposition towards the granting of Dominion status to India became one of Churchill's major political focuses. Churchill was one of the founders of the India Defence League, a group dedicated to the preservation of British power in India. In speeches and press articles in this period, he forecast widespread British unemployment and civil strife in India should independence be granted.[5]: 260 The Viceroy, Lord Irwin, who had been appointed by the prior Conservative Government, engaged in the First Round Table Conference in early 1931 and then announced the Government's policy that India should be granted Dominion status. In this the Government was supported by the Liberal Party and, officially at least, by the Conservative Party.

Churchill denounced the Round Table Conference. He spoke at public meetings in Manchester and Liverpool in January and February 1931, respectively. At both he forecast widespread unemployment into the millions and other social and economic problems in the United Kingdom if India became self-governing.[5]: 259 Though he would come to respect Mohandas Gandhi, especially after Gandhi "stood up for the untouchables",[89]: 618 at a meeting of the West Essex Conservative Association specially convened so Churchill could explain his position he said, "It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, a seditious Middle-Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well-known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace... to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor."[89]: 390 He called the Indian Congress leaders "Brahmins who mouth and patter principles of Western Liberalism."[5]: 254

In Parliament on 26 January 1931, he attacked the Government's policy, saying that the Round Table Conference "was a frightful prospect" and that he would support "effective and real organisms of provisional and local government in the provinces."[90] He returned to the Parliamentary attack on 13 March. Baldwin answered him by quoting Churchill's own speech in winding up the debate for the Lloyd George Coalition government on the Amritsar massacre, in which Churchill defended the dismissal of General Reginald Dyer. Baldwin continued by challenging Churchill and his other critics to depose him as leader of the Conservative Party.[91]

There were two incidents which damaged Churchill's reputation greatly within the Conservative Party in the period. Both were seen at the time as attacks on the Conservative leadership and as an attempt to undermine those Conservatives—and Baldwin in particular - who supported granting Dominion status to India.

The first was his speech on the eve of the St George by-election in April 1931. In a secure Conservative seat, official Conservative candidate Duff Cooper was opposed by an independent Conservative. The independent was supported by Lord Rothermere, Lord Beaverbrook, and their respective newspapers. Both press barons had tried to urge specific policies on the Conservative Party: Rothermere opposed Indian home rule, and Beaverbrook pressed for tariff reform under the slogan Empire Free Trade. Churchill's speech at the Albert Hall had been arranged before the date of the by-election had been set[5]: 262 but he made no attempt to change the date and his speech was seen as a part of the press barons' campaign against Baldwin. This was reinforced by Churchill's personal friendship with both, but especially with Beaverbrook, who wrote "The primary issue of the by-election will be the leadership of the Conservative Party. If... (the independent candidate wins) Baldwin must go."[61]: 304 Baldwin's position was strengthened when Duff Cooper won and when the civil disobedience campaign in India ceased with the Gandhi–Irwin Pact.

The second issue also affected Churchill's reputation. On 16 April 1934 Churchill claimed in Parliament that Sir Samuel Hoare and Lord Derby had pressured the Manchester Chamber of Commerce to change evidence it had given to the Joint Select Committee considering the Government of India Bill in June 1933. On 18 April he successfully moved that the matter be referred to the House of Commons Privilege Committee. He tried to cross-examine witnesses before the committee, contrary to normal procedure. Churchill himself gave evidence and Austen Chamberlain criticised the manner in which he gave it. Churchill's evidence was little and the inquiry reported to the House that there had been no breach.[5]: 269–272 The report was debated on 13 June. Churchill was unable to find a single supporter in the House and the debate ended without a division. Leo Amery accused him of pressing the matter to bring the government down stating "at all costs he had to be faithful to his chosen motto: ;Fiat justicia, ruat caelum." Churchill responded "Translate it!" Amery then remarked "I will translate it into the vernacular: 'If I can trip up Sam [Hoare] the government's bust'."[5]: 269–272

Churchill permanently broke with Stanley Baldwin over Indian independence and did not again hold any office while Baldwin was prime minister. In the index to The Gathering Storm, Churchill's first volume of his history of World War II, he records Baldwin "admitting to putting party before country" for his alleged admission that he would not have won the 1935 election if he had pursued a more aggressive policy of rearmament.[5]: 343 Churchill selectively quotes a speech in the Commons by Baldwin and gives the false impression that Baldwin is speaking of the general election when he was speaking of a by-election in 1933, and omits altogether Baldwin's actual comments about the 1935 election: "we got from the country, a mandate for doing a thing [a substantial rearmament programme] that no one, twelve months before, would have believed possible." This canard had been first put forward in the first edition of Guilty Men but in subsequent editions (including those before Churchill wrote The Gathering Storm) had been corrected.[92]

Churchill continued his campaign against any further transfer of power to Indian natives. He continued to predict conflict in India and mass unemployment at home. His speeches often quoted 19th-century politicians and his own policy was to maintain the existing Raj. In pursuing this campaign Churchill cut himself off from the mainstream of Conservative politics as much as from the rest of the political world. Younger Conservatives such as Duff Cooper, who later described Churchill's campaign as the most unfortunate event that occurred between the two wars,[93] and Harold Macmillan saw Churchill as a reactionary, someone who was completely out of touch and at base, undemocratic—leaning towards the totalitarian regimes. Churchill's public comments often seemed that way.

Elections, even in the most educated democracies are regarded as a misfortune and as a disturbance, of social, moral, and economic progress, even as a danger to international peace. Why at this moment should we force upon the untutored races of India that very system the inconveniences of which are now felt even in the most highly developed nations: the United States, Germany, France, and England herself[5]: 274

Some historians see his basic attitude to India as being set out in his book My Early Life (1930) and as being unchanged since his military service before he entered parliament. In so saying they note his references in his speeches on India to late Victorian politicians such as John Morley.[5]: 258 Historians also dispute his motives in maintaining his opposition. Some see him as trying to destabilise the National Government. In this they follow Amery (see above) and Lloyd George, who believed that with MacDonald ill and Churchill leading the Conservative right-wing, Baldwin would have to form a new Coalition in which both he and Churchill would have had key ministries.[47]: 710–712

Some historians also draw a parallel between Churchill's attitudes to India and those towards the Nazis. For example, Manfred Weidhorn in the introduction to the American edition of India (a collection of Churchill's speeches on the topic) writes.

"... Machiavelli sheds light on Churchill. The Italian notes that virtues and vices are often symbiotic rather than antithetical. Thus people say, 'Hannibal was a great general—too bad he was cruel', when the likelihood is that Hannibal was great in part because he was cruel. So here we have to consider the probability that Churchill was great in 1940 in part because he was too pugnacious, stubborn, deluded, and conservative (in the deepest sense) to be able to adjust to the New Order in Europe—traits he had shown in the matter of India."[94]

German rearmament

[edit]Churchill was wary of Adolf Hitler's potential danger as early as 1930. More than two years before Hitler took power in January 1933, Churchill warned at a dinner at the German Embassy that Hitler and his followers would start a war as soon as possible.[95] Beginning in 1932, when he opposed those who advocated giving Germany the right to military parity with France, Churchill spoke often of the dangers of German rearmament.[5]: 285–86 Later, particularly in The Gathering Storm, he portrays himself as being for a time, a lone voice in Government calling on Britain to strengthen itself against Germany.,[83]: 75 Lord Lloyd was the first to so agitate and he continued to lobby post 1930 for improvement to the Armed force and the Air Force in particular.[96] Churchill also tried to portray himself as warning against German rearmament as early as 1930 and as opposing what he saw as British disarmament at and before that time.[97] He omits the fact that as Chancellor of the Exchequer he had imposed the heavy defence cuts referred to above.

In 1931 Churchill warned against the League of Nations opposing Japan in Manchuria: "I hope we shall try in England to understand the position of Japan an ancient state.... On the one side they have the dark menace of Soviet Russia. On the other the chaos of China four or five provinces of which are being tortured under Communist rule".[5]: 329 In contemporary newspaper articles he referred to the Spanish Republican government as a Communist front, and Franco's army as the "Anti red movement" and writing "revivified Fascist Spain in closest sympathy with Italy and Germany is one kind of disaster. A Communist Spain reaching its snaky tentacles through Portugal and France is another, and many will think the worse."[5]: 408 He supported the Hoare-Laval Pact and continued up until 1937 to praise Benito Mussolini.[61]: 375 In his 1937 book Great Contemporaries, Churchill expressed a hope that despite Hitler's apparent dictatorial tendencies, he would use his power to rebuild Germany into a worthy member of the world community writing

Although no subsequent political action can condone wrong deeds, history is replete with examples of men who have risen to power by employing stern, grim, and even frightful methods, but who, nevertheless when their life is revealed as a whole, have been regarded as great figures whose lives have enriched the story of mankind. So may it be with Hitler.[98]

Churchill's first major speech on defence on 7 February 1934 stressed the need to rebuild the Royal Air Force and to create a Ministry of Defence; his second, on 13 July, urged a renewed role for the League of Nations. These three topics remained his themes until early 1936. In 1935 he was one of the founding members of "Focus in Defence of Freedom and Peace", a group which also included Sir Archibald Sinclair, Lady Violet Bonham Carter, Wickham Steed, and Professor Gilbert Murray. Focus brought together people of differing political backgrounds and occupations.[99] It led to the formation of a much wider Arms and the Covenant Movement in 1936.

When the Germany reoccupied the Rhineland in February 1936, Churchill was holidaying in Spain, and returned to a divided Britain. Labour opposition was adamant in opposing sanctions and the National Government was divided between advocates of economic sanctions and those who said that even these would lead to a humiliating backdown by Britain, as France would not support any intervention.[nb 10] Churchill's speech on 9 March was measured and praised by Neville Chamberlain as constructive but within weeks Churchill was passed over for the post of Minister for Co-ordination of Defence in favour of the Attorney General, Sir Thomas Inskip.[5]: 333–337

This surprising appointment—it surprised Inskip as much as anyone, and A. J. P. Taylor later wrote of "an appointment rightly described as the most extraordinary since Caligula made his horse a consul"[101]—came despite advice to Baldwin to broaden his cabinet. Historians have variously seen it as Baldwin's caution in not wanting to appoint someone as controversial as Churchill, as avoiding giving Germany any sign that the United Kingdom was preparing for war, and as avoiding someone who had few allies in the Conservative Party and was opposed as a war monger by some people in the United Kingdom.[nb 11] Whatever the reason, it was a severe blow to Churchill.[87]