Phentermine

| |||

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade names | Adipex-P, Ionamin, Suprenza, others | ||

| Other names | α-methyl-amphetamine α,α-dimethylphenethylamine | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| MedlinePlus | a682187 | ||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

| Dependence liability | Physical: Not typical Psychological: Moderate[1] | ||

| Addiction liability | Low[2] | ||

| Routes of administration | By mouth | ||

| Drug class | Appetite suppressant[3] | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status |

| ||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | High (almost complete)[5] | ||

| Protein binding | Approximately 96.3% | ||

| Metabolism | Liver[5] | ||

| Elimination half-life | 25 hours, urinary pH-dependent[5] | ||

| Excretion | Kidney (62–85% unchanged)[5] | ||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.112 | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C10H15N | ||

| Molar mass | 149.237 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| |||

| |||

| (verify) | |||

Phentermine, sold under the brand name Adipex-P among others, is a medication used together with diet and exercise to treat obesity.[3] It is available by itself or as the combination phentermine/topiramate.[6]

Common side effects include a fast heart beat, high blood pressure, trouble sleeping, dizziness, and restlessness.[3] Serious side effects may include abuse, but do not include pulmonary hypertension or valvular heart disease, as the latter were caused by the fenfluramine component of the fen-phen drug combination.[3] It works mainly as an appetite suppressant, likely as a result of being a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant.[3] Chemically, phentermine is a substituted amphetamine.[7]

Phentermine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1959.[3] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In 2022, it was the 149th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[8][9] Phentermine was withdrawn from the market in the United Kingdom in 2000, while the combination medication fen-phen, of which it was a part, was withdrawn from the market in 1997 due to side effects of fenfluramine.[10]

Medical uses

[edit]Phentermine is used for a short period of time to promote weight loss, if exercise and calorie reduction are not sufficient, and in addition to exercise and calorie reduction.[5][11]

Phentermine is approved for up to 12 weeks of use and most weight loss occurs in the first weeks.[11] However, significant loss continues through the sixth month and has been shown to continue at a slower rate through the ninth month.[12]

Contraindications

[edit]Use is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding,[13] or with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).[3]

Phentermine is contraindicated for users who:[5][11]

- have a history of drug abuse

- are allergic to sympathomimetic amine drugs

- are taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) or have taken one within the last 14 days

- have cardiovascular disease, hyperthyroidism, or glaucoma

- are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or breastfeeding.

Adverse effects

[edit]Tolerance usually occurs; however, risks of dependence and addiction are considered negligible.[12][14] People taking phentermine may be impaired when driving or operating machinery.[11] Consumption of alcohol with phentermine may produce adverse effects.[11]

There is currently no evidence regarding whether or not phentermine is safe for pregnant women.[5][11]

Other adverse effects include:[5][11]

- Cardiovascular effects like palpitations, tachycardia, high blood pressure, precordial pain; rare cases of stroke, angina, myocardial infarction, cardiac failure and cardiac arrest have been reported.

- Central nervous system effects like overstimulation, restlessness, nervousness, insomnia, tremor, dizziness and headache; there are rare reports of euphoria followed by fatigue and depression, and very rarely, psychotic episodes and hallucinations.

- Gastrointestinal effects include nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, cramps, unpleasant taste, diarrhea, and constipation.

- Other adverse effects include trouble urinating, rash, impotence, changes in libido, and facial swelling.

Interactions

[edit]Phentermine may decrease the effect of drugs like clonidine, methyldopa, and guanethidine. Drugs to treat hypothyroidism may increase the effect of phentermine.[11]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

Phentermine has some similarity in its pharmacodynamics with its parent compound, amphetamine, as they both are TAAR1 agonists,[15] where the activation of TAAR1 in monoamine neurons facilitates the efflux, or release into the synapse, of these neurochemicals. At clinically relevant doses, phentermine primarily acts as a releasing agent of norepinephrine in neurons, although, to a lesser extent, it releases dopamine and serotonin into synapses as well.[14][16] Phentermine may also trigger the release of monoamines from VMAT2, which is a common pharmacodynamic effect among substituted amphetamines. The primary mechanism of phentermine's action in treating obesity is the reduction of hunger perception, which is a cognitive process mediated primarily through several nuclei within the hypothalamus (in particular, the lateral hypothalamic nucleus, arcuate nucleus, and ventromedial nucleus). Outside the brain, phentermine releases norepinephrine and epinephrine – also known as noradrenaline and adrenaline respectively – causing fat cells to break down stored fat as well.

History

[edit]In 1959, phentermine first received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an appetite suppressant.[17] Eventually a hydrochloride salt and a resin form became available.[17]

Phentermine was marketed with fenfluramine or dexfenfluramine as a combination appetite suppressant and fat burning agent under the popular name fen-phen.[18] In 1997, after 24 cases of heart valve disease in fen-phen users, fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine were voluntarily taken off the market at the request of the FDA.[19] Studies later showed nearly 30% of people taking fenfluramine or dexfenfluramine for up to 24 months had abnormal valve findings.[20]

Phentermine is still available by itself in most countries, including the US.[17] However, because it is similar to amphetamine, it is classified as a controlled substance in many countries. Internationally, phentermine is a schedule IV drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[21] In the United States, it is classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act. In contrast, amphetamine preparations are classified as Schedule II controlled substances.[22]

A company called Vivus developed a combination drug, phentermine/topiramate that it originally called Qnexa and then called Qsymia, which was invented and used off-label by Thomas Najarian, who opened a weight-clinic in Los Osos, California in 2001; Najarian had previously worked at Interneuron Pharmaceuticals, which had developed one of the fen-phen drugs previously withdrawn from the market.[23] The FDA rejected the combination drug in 2010 due to concerns over its safety.[23] In 2012 the FDA approved it after Vivus re-applied with further safety data.[24] At the time, one obesity specialist estimated that around 70% of his colleagues were already prescribing the combination off-label.[23]

Chemistry

[edit]Phentermine is a substituted amphetamine which has a methyl group on amphetamine's alpha carbon.[7] It is a positional isomer of methamphetamine and other methylamphetamines. The molecular formula of phentermine is C10H15N.

Names

[edit]The term ‘phentermine' is contracted from phenyl-tertiary-butyl amine.

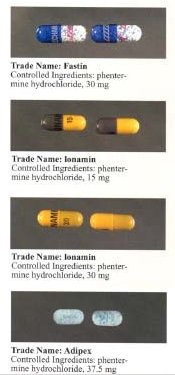

It is marketed under many brand names and formulations worldwide, including Acxion, Adipex, Adipex-P, Duromine, Elvenir, Fastin, Ionamin, Lomaira (phentermine hydrochloride), Panbesy, Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate), Razin, Redusa, Sentis, Suprenza, and Terfamex.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2017 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2016. p. 7. ISBN 9781284118971.

- ^ Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (2010). Kaplan and Sadock's Pocket Handbook of Clinical Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 435. ISBN 9781605472645.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Phentermine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "METERMINE (Phentermine)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. iNova Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Limited. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ "Phentermine and topiramate Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ a b Hagel JM, Krizevski R, Marsolais F, Lewinsohn E, Facchini PJ (July 2012). "Biosynthesis of amphetamine analogs in plants". Trends in Plant Science. 17 (7): 404–412. Bibcode:2012TPS....17..404H. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.03.004. PMID 22502775.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Phentermine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Bagchi D, Preuss HG (2012). Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Prevention (Second ed.). CRC Press. p. 314. ISBN 9781439854259.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Phentermine label at FDA" (Last updated: January 2012). FDA. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ a b Glazer G (August 2001). "Long-term pharmacotherapy of obesity 2000: a review of efficacy and safety". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (15): 1814–1824. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.15.1814. PMID 11493122.

- ^ "Phentermine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ a b Haslam D (March 2016). "Weight management in obesity - past and present". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 70 (3): 206–217. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12771. PMC 4832440. PMID 26811245.

- ^ Barak LS, Salahpour A, Zhang X, Masri B, Sotnikova TD, Ramsey AJ, et al. (September 2008). "Pharmacological characterization of membrane-expressed human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) by a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer cAMP biosensor". Molecular Pharmacology. 74 (3): 585–594. doi:10.1124/mol.108.048884. PMC 3766527. PMID 18524885.

we confirmed agonistic activity at human TAAR1 of several other compounds, including the trace amines octopamine and tryptamine, the amphetamine derivatives l-amphetamine, d-methamphetamine, (+)-MDMA, and phentermine, and the catecholamine metabolites 3-MT and 4-MT (Bunzow et al., 2001; Lindemann and Hoener, 2005; Reese et al., 2007; Wainscott et al., 2007; Wolinsky et al., 2007; Xie and Miller, 2007; Xie et al., 2007).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, et al. (January 2001). "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707. S2CID 15573624.

- ^ a b c Ryan DA, Bray GA (2014). "Sibutramine, Phentermine, and Diethylproprion: Sympathomimetic Drugs in the Management of Obesity". In Bray GA, Bouchard C (eds.). Handbook of Obesity - Volume 2 Clinical Applications (Fourth ed.). Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 234. ISBN 9781841849829.

- ^ Kolata G (23 September 1997). "How Fen-Phen, A Diet 'Miracle,' Rose and Fell". New York Times. NY, NY, USA.

- ^ "FDA Announces Withdrawal Fenfluramine and Dexfenfluramine (Fen-Phen)". Fda.gov. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Weigle DS (June 2003). "Pharmacological therapy of obesity: past, present, and future". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 88 (6): 2462–2469. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030151. PMID 12788841.

- ^ Convention on Psychotropic Substances Archived 14 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rueda-Clausen CF, Padwal RS, Sharma AM (August 2013). "New pharmacological approaches for obesity management". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 9 (8): 467–478. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.113. PMID 23752772. S2CID 20072687.

- ^ a b c Pollack A (16 February 2012). "Diet Treatment, Already in Use, to Get F.D.A. Review". The New York Times.

- ^ "FDA approves weight-management drug Qsymia". FDA. 17 July 2012.

- ^ "International brands for phentermine". Drugs.com. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

External links

[edit]- "Phentermine". International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). the World Health Organization (WHO).