Rewilding

Rewilding is a form of ecological restoration aimed at increasing biodiversity and restoring natural processes. It differs from other forms of ecological restoration in that rewilding aspires to reduce human influence on ecosystems.[1] It is also distinct from other forms of restoration in that, while it places emphasis on recovering geographically specific sets of ecological interactions and functions that would have maintained ecosystems prior to human influence, rewilding is open to novel or emerging ecosystems which encompass new species and new interactions.[2][3]

A key feature of rewilding is its focus on replacing human interventions with natural processes. Rewilding enables the return of intact, large mammal assemblages, to promote the restoration of trophic networks.[4] This mechanism of rewilding is a process of restoring natural processes by introducing or re-introducing large mammals to promote resilient, self-regulating, and self-sustaining ecosystems.[5][6] Large mammals can influence ecosystems by altering biogeochemical pathways as they contribute to unique ecological roles, they are landscape engineers that aid in shaping the structure and composition of natural habitats.[7][8] Rewilding projects are often part of programs for habitat restoration and conservation biology, and should be based on sound socio-ecological theory and evidence.[9]

While rewilding initiatives can be controversial, the United Nations has listed rewilding as one of several methods needed to achieve massive scale restoration of natural ecosystems, which they say must be accomplished by 2030[10] as part of the 30x30 campaign.[11]

Origin

[edit]The term rewilding was coined by members of the grassroots network Earth First!, first appearing in print in 1990.[12] It was refined and grounded in a scientific context in a paper published in 1998 by conservation biologists Michael Soulé and Reed Noss.[13] Soulé and Noss envisaged rewilding as a conservation method based on the concept of 'cores, corridors, and carnivores'.[14] The key components of rewilding incorporate large core protected areas, keystone species, and ecological connectivity based on the theory that large predators play regulatory roles in ecosystems.[15] '3Cs' rewilding therefore relied on protecting 'core' areas of wild land, linked together by 'corridors' allowing passage for 'carnivores' to move around the landscape and perform their functional role.[16] Inside these cores, human development, especially the building of roads, is strictly limited. National parks and wilderness reserves are the most common types of 'core' areas. Soulé and fellow biologist John Terbough expanded on the concept of corridors in their book Continental Conservation. They determined that one size does not fit all: narrow, linear corridors might work for some smaller species, but if conservationists wanted to encourage the movement of large carnivores, they needed to make corridors wide enough to allow for daily and seasonal movement of both herds of prey and packs of their predators.[17] The '3Cs' concept was developed further in 1999[18] and Earth First co-founder, Dave Foreman, subsequently wrote a full-length book on rewilding as a conservation strategy.[19]

History

[edit]Rewilding was developed as a method to preserve functional ecosystems and reduce biodiversity loss, incorporating research in island biogeography and the ecological role of large carnivores.[20] In 1967, The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson established the importance of considering the size and fragmentation of wildlife conservation areas, stating that protected species and areas remained vulnerable to extinctions if populations were small and isolated.[21] In 1987, William D. Newmark's study of extinctions in national parks in North America added weight to the theory.[22] The publications intensified debates on conservation approaches.[23] With the creation of the Society for Conservation Biology in 1985, conservationists began to focus on reducing habitat loss and fragmentation.[24]

Supporters of rewilding initiatives range from individuals, small land owners, local non-governmental organizations and authorities, to national governments and international non-governmental organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature. While rewilding efforts can be well regarded, the increased popularity of rewilding has generated controversy, especially in relation to large-scale projects. These have sometimes attracted criticism from academics and practicing conservationists, as well as government officials and business people.[25][26][27][28] Nonetheless, a 2021 report for the launch of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, the United Nations listed rewilding as one of several restoration methods which they state should be used for ecosystem restoration of over 1 billion hectares.[29][30]

Guiding principles

[edit]Since its origin, the term rewilding has been used as a signifier of particular forms of ecological restoration projects that have ranged widely in scope and geographic application. In 2021 the journal Conservation Biology published a paper[2] by 33 coauthors from around the world. Titled 'Guiding Principles for Rewilding', researchers and project leaders from North America (Canada, Mexico and the United States) joined with counterparts in Europe (Denmark, France, Hungary, The Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK), China, and South America (Chile and Colombia) to produce a unifying description, along with a set of ten guiding principles.

The group wrote, 'Commonalities in the concept of rewilding lie in its aims, whereas differences lie in the methods used, which include land protection, connectivity conservation, removing human infrastructure, and species reintroduction or taxon replacement.' Referring to the span of project types they stated, 'Rewilding now incorporates a variety of concepts, including Pleistocene megafauna replacement, taxon replacement, species reintroductions, retrobreeding, release of captive-bred animals, land abandonment, and spontaneous rewilding.' [2]

Empowered by a directive from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to produce a document on rewilding that reflected a global scale inventory of underlying goals as well as practices, the group sought a 'unifying definition', producing the following:

'Rewilding is the process of rebuilding, following major human disturbance, a natural ecosystem by restoring natural processes and the complete or near complete food web at all trophic levels as a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem with biota that would have been present had the disturbance not occurred. This will involve a paradigm shift in the relationship between humans and nature. The ultimate goal of rewilding is the restoration of functioning native ecosystems containing the full range of species at all trophic levels while reducing human control and pressures. Rewilded ecosystems should—where possible—be self-sustaining. That is, they require no or minimal management (i.e., natura naturans [nature doing what nature does]), and it is recognized that ecosystems are dynamic.'[2]

Ten principles were developed by the group:

- Rewilding utilizes wildlife to restore trophic interactions.

- Rewilding employs landscape-scale planning that considers core areas, connectivity, and co-existence.

- Rewilding focuses on the recovery of ecological processes, interactions, and conditions based on reference ecosystems.

- Rewilding recognizes that ecosystems are dynamic and constantly changing.

- Rewilding should anticipate the effects of climate change and where possible act as a tool to mitigate impacts.

- Rewilding requires local engagement and support.

- Rewilding is informed by science, traditional ecological knowledge, and other local knowledge.

- Rewilding is adaptive and dependent on monitoring and feedback.

- Rewilding recognizes the intrinsic value of all species and ecosystems.

- Rewilding requires a paradigm shift in the coexistence of humans and nature.[2]

A paper was published in 2024 that offered a "broad study of rewilding guidelines and interventions."[31]

Rewilding and climate change

[edit]Rewilding can respond to both the causes and effects of climate change and has been posited as a 'natural climate solution'. Rewilding's creation of new ecosystems and restoration of existing ones can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation through, inter alia, carbon capture and storage, altering the Earth's albedo, natural flood management, reduction of wildfire risk, new habitat creation, and enabling or facilitating the movement of species to new, climate safe habitats, thus protecting biodiversity and maintaining functioning, climate resilient ecosystems.[32][33][34][35][36][37][38]

The functional roles animals perform in ecosystems, such as grazing, nutrient cycling and seed distribution, can influence the amount of carbon that soils and (marine and terrestrial) plants capture.[39] The carbon cycle is altered through herbivores consuming vegetation, assimilating carbon within their own biomass, and releasing carbon by respiration and defecation after digestion.[40][41] The most beneficial effects on biogeochemical cycling and ecosystem structure are reported through rewilding large herbivore species.[42][43] A study in a tropical forest in Guyana found that an increase in mammal species from 5 to 35 increased tree and soil carbon storage by four to five times, compared to an increase of 3.5 to four times with an increase of tree species from 10 to 70.[44] A separate study suggested that the loss of megafauna that eat fruits may be responsible for an up to 10% reduction in carbon storage in tropical forests.[45] Furthermore, acceleration of nutrient cycling through browsing and grazing may increase local plant productivity and thereby maintain ecosystem productivity in grassy biomes.

It is also posited that grazing and browsing reduces the risk of wildfires (which are significant contributors of GHG emissions and whose smoke can alter the planet's albedo - the Earth's ability to reflect heat from sunlight)). For example, the loss of wildebeest from the Serengeti led to an increase in un-grazed grass, leading to more frequent and intense fires, causing the grassland to turn from a carbon sink to a carbon source. When disease management practices restored the wildebeest population, the Serengeti returned to a carbon sink state.[39][46]

Rewilding's effect on albedo is not only through potential reduction of smoke from wildfires but also through the effects of grazing itself. By reducing woody cover through browsing and trampling, large herbivores expose more ground surface and thus increase the albedo effect, reducing local surface temperatures and creating a net surface cooling effect during spring and autumn.

Other forms of ecological restoration as part of rewilding can also assist with mitigating climate change. For example, reforestation, afforestation and peat re-wetting can all contribute to carbon sequestration. [47] While carbon sequestration could allow carbon offsetting and carbon trading as a way to monetize rewilding there has been concern that the highly speculative nature of carbon markets encourages 'land grabbing' (i.e., buying large areas of land) and 'greenwashing' from natural capital investors and multi-national companies.[48]

Types of rewilding

[edit]Passive rewilding

[edit]

Passive rewilding (also referred to as ecological rewilding)[49] aims to restore natural ecosystem processes via minimal or the total withdrawal of direct human management of the landscape.[50][51][52]

Active rewilding

[edit]Active rewilding is an umbrella term used to describe a range of rewilding approaches all of which involve human intervention. These might include species reintroductions or translocations and/or habitat engineering and the removal of man-made structures.[53][50][54]

Pleistocene rewilding

[edit]Pleistocene rewilding is the (re)introduction of extant Pleistocene megafauna, or the close ecological equivalents of extinct megafauna, to restore ecosystem function. Advocates of the approach maintain that ecosystems where species evolved in response to Pleistocene megafauna but now lack large mammals may be in danger of collapse.[55][56] Meanwhile critics argue that it is unrealistic to assume that ecological communities today are functionally similar to their state 10,000 years ago.

Trophic rewilding

[edit]Trophic rewilding is an ecological restoration strategy focused on restoring trophic interactions and complexity (specifically top-down and associated trophic cascades where a top consumer/predator controls the primary consumer population) through species (re)introductions, in order to promote self-regulating, biodiverse ecosystems.[57][58]

Urban rewilding

[edit]Urban rewilding is a type of rewilding focused on the integration of nature into urban settings.[59]

Elements

[edit]Ecosystem engineers

[edit]Ecosystem engineers are ‘organisms that demonstrably modify the structure of their habitats’. [60] Examples of ecosystem engineers in rewilding include beaver, elephants, bison, elk, cattle (as analogues for the extinct aurochs) and pigs (as analogues for wild boar).[61][62][63][64]

Keystone species

[edit]A keystone species is a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its environment relative to its abundance.

Predators

[edit]Apex predators may be required in rewilding projects to ensure that browsing and grazing animals are kept from over-breeding/over-feeding thereby destroying vegetation complexity[20] and exceeding the ecological carrying capacity of the rewilding area, as was seen in the mass-starvations which occurred at the Oostvaardersplassen rewilding project in the Netherlands.[65] While predators play an important role in ecosystems, however, there is debate regarding the extent to which the control of prey populations is due to direct predation or a more indirect influence of predators (see Ecology of fear).[66] For example, it is thought that wildebeest populations in the Serengeti are primarily controlled by food constraints despite the presence of many predators.[67]

Criticism

[edit]Compatibility with economic activity

[edit]Some national governments and officials within multilateral agencies such as the United Nations, express the view that 'excessive' rewilding, such as large rigorously enforced protected areas where no extraction activities are allowed, can be too restrictive on people's ability to earn sustainable livelihoods.[27][28] The alternative view is that increasing ecotourism can provide employment.[68]

Conflicts with animal rights and welfare

[edit]Rewilding has been criticized by animal rights scholars, such as Dale Jamieson, who argues that 'most cases of rewilding or reintroducing are likely to involve conflicts between the satisfaction of human preferences and the welfare of nonhuman animals'.[69] Erica von Essen and Michael Allen, using Donaldson and Kymlicka's political animal categories framework, assert that wildness standards imposed on animals are arbitrary and inconsistent with the premise that wild animals should be granted sovereignty over the territories that they inhabit and the right to make decisions about their own lives. To resolve this, von Essen and Allen contend that rewilding needs to shift towards full alignment with mainstream conservation and welcome full sovereignty, or instead take full responsibility for the care of animals who have been reintroduced.[70] Ole Martin Moen argues that rewilding projects should be brought to an end because they unnecessarily increase wild animal suffering and are expensive, and the funds could be better spent elsewhere.[71]

Erasure of environmental history

[edit]The environmental historian Dolly Jørgensen argues that rewilding, as it currently exists, 'seeks to erase human history and involvement with the land and flora and fauna. Such an attempted split between nature and culture may prove unproductive and even harmful.' She calls for rewilding to be more inclusive to combat this.[72] Jonathan Prior and Kim J. Ward challenge Jørgensen's criticism and provide examples of rewilding programs which 'have been developed and governed within the understanding that human and non-human world are inextricably entangled'.[73]

Farming

[edit]Some farmers have been critical of rewilding for 'abandoning productive farmland when the world's population is growing'.[74] Farmers have also attacked plans to reintroduce the lynx in the United Kingdom because of fears that reintroduction will lead to an increase in sheep predation.[75]

Harm to conservation

[edit]Some conservationists have expressed concern that rewilding 'could replace the traditional protection of rare species on small nature reserves', which could potentially lead to an increase in habitat fragmentation and species loss.[74] David Nogués-Bravo and Carsten Rahbek assert that the benefits of rewilding lack evidence and that such programs may inadvertently lead to 'de-wilding', through the extinction of local and global species. They also contend that rewilding programs may draw funding away from 'more scientifically supported conservation projects'.[76] Many large conservation groups have built fundraising campaigns around the idea that once wildlife is gone, it’s gone for good; rewilding experts saying otherwise may confuse donors and lead to less money being funneled into conservation efforts. Governmental agencies overseeing land use and consumption are often heavily influenced by the interests of loggers, ranchers, and miners, so non-profit organizations are often at the forefront of conservation efforts, and a loss of funding could have major impacts on the protection of wildlife. There is also concern among conservationists that if the idea that wilderness can be restored becomes popular with the public, oil companies, real estate developers, and agribusinesses may be emboldened to step up land consumption, arguing that it can be restored later. [77]

Human-wildlife conflict

[edit]The reintroduction of brown bears to Italy's Trentino province through the EU-funded Life Ursus project has led to growing tensions between humans and wildlife. While initially celebrated as a conservation success, the bear population has expanded to over 100, leading to increased conflicts, including the fatal attack on Andrea Papi in 2023—the first modern death caused by a wild bear in Italy. This incident sparked fear among residents and prompted calls for stricter controls, including culling dangerous bears. Critics argue the conflict stems from poor management, inadequate public education, and a lack of preventive measures like bear-proof bins. Despite efforts to balance human safety and conservation, local communities remain deeply divided, with many pushing for limits on bear numbers and more decisive action against perceived threats.[78][79]

Rewilding in different locations

[edit]Both grassroots groups and major international conservation organizations have incorporated rewilding into projects to protect and restore large-scale core wilderness areas, corridors (or connectivity) between them, and apex predators, carnivores, or keystone species. Projects include: the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative in North America (also known as Y2Y), the European Green Belt (built along the former Iron Curtain), transboundary projects (including those in southern Africa funded by the Peace Parks Foundation), community-conservation projects (such as the wildlife conservancies of Namibia and Kenya), and projects organized around ecological restoration (including Gondwana Link, regrowing native bush in a hotspot of endemism in southwest Australia, and the Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, restoring dry tropical forest and rainforest in Costa Rica).[80]

North America

[edit]

In North America, a major project aims to restore the prairie grasslands of the Great Plains.[81] The American Prairie is reintroducing bison on private land in the Missouri Breaks region of north-central Montana, with the goal of creating a prairie preserve larger than Yellowstone National Park.[81]: 187–199 As of 2024, American Prairie's habitat spanned over 520,000 acres.[82]

Dam removal has led to the restoration of many river systems in the Pacific Northwest in an effort to restore salmon populations specifically but with other species in mind. As stated in an article on environmental law:

'These dam removals provide perhaps the best example of large-scale environmental remediation in the twenty-first century. [...] The result has been to put into motion ongoing rehabilitation efforts in four distinct river basins: the Elwha and White Salmon in Washington and the Sandy and Rogue in Oregon'.[83]

Yellowstone to Yukon

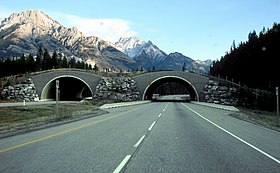

[edit]Formally launched in 1997, Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) was a conservation initiative that envisioned a wide corridor of protected land stretching from Canada’s Yukon territory, through American national parks like Waterton and Glacier, all the way to the Greater Yellowstone ecoregion in the northern Rocky Mountains. [84] Promoters of the project worked to discourage building of roads and other human developments that would impede the movement of large predators like wolves and grizzly bears. Y2Y used lobbying and education to promote its mission and get the public involved. Organizers set up conferences between rewilding groups in Canada and the United States, facilitated dialogue between conservationists and Native American groups, and maintained high visibility for the project by featuring in newspapers like the New York Times and the Washington Post. Activists involved in the project successfully lobbied for 24 highway crossing structures in the Banff area, allowing for safer movement of wildlife across the Trans-Canadian highway. [85]

Y2Y inspired other conservation groups to focus more of their efforts on lobbying to persuade government action, and led to an increase in corridor planning across North America. The South Coast Wildlands Project successfully convinced the California State Parks Agency to buy a 700 acre tract slated for development. The Algonquin to Adirondack initiative, modeled after Y2Y, has focused research efforts on improving connectivity around the Great Lakes Region. Conservation groups from the United States and Canada have worked together to plan a series of marine priority areas from Baja California to the Bering Sea, allowing both nations to protect species of mutual concern. [86]

Protecting Predators

[edit]There have been multiple projects launched to protect North America’s carnivores, one of the main components of the ‘3 C’s’ approach to rewilding. Reed Noss, an early advocate for rewilding, began working on reserve designs as early as the 1980s to protect Florida’s largest predators: the Florida panther and the Florida black bear. Noss’ initial plan envisioned 60% of Florida’s land set aside for wildlife reserves, and proved so influential that the Florida State legislature set aside $3.2 billion to buy land for a network of reserves and corridors between them. [77]

At the same time, a group based in Washington D.C. called Defenders of Wildlife began promoting protection of predators across the country, including grizzly bears, wolves, and river otters. In 1987, they set up the Bailey Wildlife Foundation Wolf Compensation Trust to pay ranchers back for the loss of livestock due to predation in an attempt to raise support for rewilding among farmers, who are often some of the most vocal opponents of the conservation of large predators. In 1998, they launched another program to pay for fencing, alarms, and other methods that would protect livestock in a way that didn’t harm predators. However, this approach has been largely unsuccessful at bolstering the native wolf population because of continued shooting of wolves, both illegally and permitted by the USFWS. [77]

New York

[edit]Fresh Kills landfill, located on Staten Island, was once home to 150 million tons of trash. However, plans created between 2001 and 2006 reimagined it as a 2,200 acre park, the largest park built in the state of New York in over a century. Construction began in 2008 to restore the area back to its original wetland ecosystem, complete with open waterways, sweet-gum swamps, prairies, and meadows of wildflowers. Part of initial plans involved removing invasive reed species and replacing them native marsh grasses. The project is slated to take up to thirty years to complete, with the end goal of combining ecological restoration with recreational activities. [77]

While planning for Fresh Kills Park, New York State initiated an even more ambitious program focused on protecting the broader ecosystem around Staten Island by restoring the Hudson River. In 2005, the organizations involved came up with a few goals for the project: re-invigorating the river’s fisheries, improving water quality by removing contaminants, and preserving shoreline and forested habitats upriver. When the project is complete, it will affect fifty thousand acres containing six different habitat types. [77]

Mexico

[edit]In the Mexican state of Sonora, the Northern Jaguar Project bought 45,000 acres of land by 2007 devoted to protecting the northernmost breeding population of jaguars. The group also encouraged local people to help them monitor the population by offering a $500 reward for each photograph of a living cat taken by ranch owners who promised not to shoot jaguars on their property. In its first year, the program paid out $6,500 for photos of jaguars, mountain lions, and ocelots. [77]

Central America

[edit]Paseo Pantera/Mesoamerican Biological Corridor

[edit]In the early 1990s, the Wildlife Conservation Society proposed a plan for a major corridor project that would span from Southern Mexico down into Panama, connecting existing reserves, parks, and undisturbed forests of all seven Central American countries and the lower five Mexican states. They called the plan “Paseo Pantera,” or “the path of the panther,” named so because of the movement of mountain lions throughout the area. [77] The plan attracted a lot of controversy: indigenous peoples were concerned that their land would be taken from them to be converted into parks, and some activists claimed that the program was setting the environment above human needs. These arguments caused the project to be reviewed and refashioned. In 1997, the new plan, renamed the “Mesoamerican Biological Corridor,” was unveiled as a conservation project that also promoted the welfare of indigenous people and local economies. [77]

Despite the changes, the Mesoamerican Corridor still had some flaws, most notably with regard to land use. The plan necessitated reaching agreements with numerous villages to decide what zoning for protected areas meant for the local people, how it would be enforced, and where hunting and fishing would be allowed. Rural people were largely unimpressed with the vague nature of the outline, so progress was slow. In 2005, the Central American Free Trade Agreement promised to develop many of the same areas the Mesoamerican Corridor sought to protect, but conservationists refused to oppose the development for fear of losing funding. By 2006, hundreds of millions of dollars had been spent on preserving the corridor, but only one small protected area had been created. [77]

Costa Rica

[edit]Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. In 1975, the Nature Conservancy worked with the Costa Rican government to create the first national park in the country: Corcovado. The park originally spanned 86,000 acres, nearly a third of the peninsula. The Nature Conservancy wanted to establish it as a refuge for the dozens of endemic species that occur in this small stretch of habitat. [77] However, the project has faced many setbacks since its establishment. Conservationists quickly realized that it was too small to protect many critical species, including the jaguar, peccary, and harpy eagle. Gold was discovered in Corcovado around the same time as the park was established, and some of the natural areas within the park were illegally destroyed by miners. Programs to engage local people in conservation efforts quickly failed because of a lack of funding, causing people living on the border to become increasingly hostile towards the project. Lack of financial resources caused many people to resort to poaching within the park’s borders or shooting jaguars that ate their crops. [77]

Conservation groups hoped to solve these problems by launching another initiative, the Osa Biological Corridor project. The plan was designed to enlarge currently protected areas on the peninsula, and hopes to devote $10 million to develop community support for rewilding by providing education programs and new jobs protecting the reserves. [77]

South America

[edit]Argentina

[edit]In 1997, Douglas and Kris Tompkins created 'The Conservation Land Trust Argentina' with the goal of transforming the Iberá Wetlands. In 2018, thanks to a team of conservationists and scientists, and a donation of 195,094 ha (482,090 acres) of land by Kris Tompkins, an area was converted into a National Park, and jaguar (a species that had been extinct in the region for seven decades), anteaters and giant otters were reintroduced. A spin-off of the Tompkins Foundation, Rewilding Argentina, is an organization dedicated to the restoration of El Impenetrable National Park, in Chaco, Patagonia Park, in Santa Cruz, and the Patagonian coastal area in the province of Chubut, in addition to Iberá National Park.[87]

Brazil

[edit]The red-rumped agouti and the brown howler monkey were reintroduced in Tijuca National Park (Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil), between 2010 and 2017 with the goal of restoring seed dispersal.[88] Prior to the reintroductions, the national park did not have large or intermediate -sized seed dispersers, the increased dispersal of tree seeds following the reintroductions therefore had a significant effect on forest regeneration in the park.[88] This is significant since the Tijuca National Park is part of heavily fragmented Atlantic Forest and there is potential to restore many more seed dispersal interactions if seed dispersing mammals and birds are reintroduced to forest patches where the tree species diversity remains high.[89]

The Cerrado-Pantanal Ecological Corridors Project was proposed in the 1990s to restore connectivity between two of Brazil’s core reserves: Emas National Park and the Pantanal, one of the world’s largest wetlands. [77] It made significant progress in the early 2000s because of plans to conserve mainly areas with low human density. Another reason for wider support was because of a fund started to compensate farmers that lost livestock to the big cats that conservationists hope to protect using these corridors, and healthcare programs that provided free services to ranchers who committed to not killing critically endangered jaguars. [77]

Australia

[edit]Colonisation has had a significant impact on Australia's native flora and fauna, and the introduction of red foxes and cats has devastated many of the smaller ground-dwelling mammals. The island state of Tasmania has become an important location for rewilding efforts because, as an island, it is easier to remove feral cat populations and manage other invasive species. The reintroduction and management of the Tasmanian devil in this state, and dingoes on the mainland, is being trialed in an effort to contain introduced predators, as well as over-populations of kangaroos.[90]

Gondwana Link, a plan conceived in 2002, was devised to connect two Australian national parks: Stirling Range and Fitzgerald River National Park. Much of this land had been severely degraded by harmful farming practices, and was barren of most plant and animal life. Organizers of the project worked on revegetating the land with native plant species, fifty of which were found nowhere else on Earth, in the hopes that they would attract wildlife back to the area. [77] Five years later, they had planted over 100 species of native plants, and multiple reptiles species had been spotted coming back to the region. By 2009, the Gondwana Link included over 23,000 acres of protected land. [77]

WWF-Australia runs a program called 'Rewilding Australia' whose projects include restoring the platypus in the Royal National Park, south of Sydney, eastern quolls in the Booderee National Park in Jervis Bay and at Silver Plains in Tasmania, and brush-tailed bettongs in the Marna Banggara project on the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia.[91] Other projects around the country include:[90]

- Barrington Wildlife Sanctuary, NSW

- Mongo Valley, NSW

- Bungador Stoney Rises Nature Reserve, Victoria

- Mount Zero-Taravale Sanctuary, Queensland

- Dirk Hartog Island National Park, Western Australia

- Marna Banggara, SA

- Clarke Island/Lungtalanana, Tasmania

Europe

[edit]

In 2011, the 'Rewilding Europe' initiative was established with the aim of rewilding one million hectares of land in ten areas including the western Iberian Peninsula, Velebit, the Carpathians and the Danube delta by 2020.[92] The project considers reintroductions of species that are still present in Europe such as the Iberian lynx, Eurasian lynx, grey wolf, European jackal, brown bear, chamois, Iberian ibex, European bison, red deer, griffon vulture, cinereous vulture, Egyptian vulture, great white pelican and horned viper, along with primitive domestic horse and cattle breeds as proxies for the extinct tarpan and aurochs (the wild ancestors of domestic cattle) respectively. Since 2012, Rewilding Europe has been heavily involved in the Tauros Programme, which seeks to create a breed of cattle that resembles the aurochs by selectively breeding existing breeds of cattle.[93] Projects also employ domestic water buffalo as a grazing analogue for the extinct European water buffalo.[94]

European Wildlife, established in 2008, advocates the establishment of a European Centre of Biodiversity at the German–Austrian–Czech borders, and the Chernobyl exclusion zone in Ukraine.

European Green Belt

[edit]The European Green Belt is a proposed rewilding zone that is envisioned running through over a dozen European countries using land that was historically part of the physical boundaries of the Iron Curtain. When completed, the European Green Belt will stretch over five thousand miles, from the Barents Sea off the northern coast of Norway to the Black Sea in southeast Europe. [77] The corridor is composed of three main sections: the Fennoscandian Green Belt running through Norway, Finland, and Russia, the Central Green Belt located in parts of Germany, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, and Italy, and the Balkan Green Belt in Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece, and Turkey. It will link core reserves and parks like the Bavarian Forest in Germany, the Danube-March floodplains in Austria and Slovakia, and Sumava National Park in the Czech Republic. Proponents of the European Green Belt hope that it will increase ecotourism and sustainable farming practices across Europe. [77]

Austria

[edit]Der Biosphärenpark Wienerwald was created in Austria in 2003 with 37 kernzonen (core zones) covering a total of 5,400 ha designated free from human interference.[95]

Britain

[edit]

Rewilding Britain, a charity founded in 2015, aims to promote rewilding in Britain and is a leading advocate of rewilding.[96] Rewilding Britain has laid down 'five principles of rewilding' which it expects to be followed by affiliated rewilding projects.[97][98] These are to support people and nature together, to 'let nature lead', to create resilient local economies, to 'work at nature's scale', and to secure benefits for the long-term.

Celtic Reptile and Amphibian is a limited company established in 2020, with the aim of reintroducing extinct species of reptile and amphibian (such as the European pond turtle,[99] moor frog, agile frog,[100] common tree frog and pool frog)[101][102] to Britain. Success has already been achieved with the captive breeding of the moor frog.[103][104] A reintroduction trial of the European pond turtle to its historic, Holocene range in the East Anglian Fens, Brecks and Broads has been initiated, with support from the University of Cambridge.[105]

In 2020, nature writer Melissa Harrison reported a significant increase in attitudes supportive of rewilding among the British public, with plans recently approved for the release of European bison, Eurasian elk, and great bustard in England, along with calls to rewild as much as 20% of the land in East Anglia, and even return apex predators such as the Eurasian lynx, brown bear, and grey wolf.[106][107][61] More recently, academic work on rewilding in England has highlighted that support for rewilding is by no means universal. As in other countries, rewilding in England remains controversial to the extent that some of its more ambitious aims are being 'domesticated' both in a proactive attempt to make it less controversial and in reactive response to previous controversy.[108] Projects may also refer to their activity using terminology other than 'rewilding', possibly for political and diplomatic reasons, taking account of local sentiment or possible opposition. Examples include 'Sanctuary Nature Recovery Programme' (at Broughton) and 'nature restoration project', the preferred term used by the Cambrian Wildwood project, an area aspiring to encompass 7,000 acres in Wales.[109]

Notable rewilding sites include:

- Knepp Wildland. The 3,500 acre (1,400 hectare)[110] Knepp Castle estate in West Sussex was the first major pioneer of rewilding in England, and started that land-management policy there in 2001[111][112] on land formerly used as dairy farmland.[110] Rare species including common nightingale, turtle doves, peregrine falcons and purple emperor butterflies are now breeding at Knepp and populations of more common species are increasing.[113] In 2019 a pair of white storks built a nest in an oak tree at Knepp. The storks were part of a group imported from Poland as a result of a programme to reintroduce the species to England run by the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation which has overseen reintroductions of other bird species to the UK.[114]

- Broughton Hall Estate, Yorkshire. In 2021, approximately 1,100 acres (a third of the estate)[115] was devoted to rewilding with advice from Prof. Alastair Driver of Rewilding Britain.[116]

- Mapperton Estate, Dorset. In 2021, a 200 acre farm (one of the five farms composing the estate) began the process of rewilding.[117]

- Alladale Wilderness Reserve, Sutherland, Scotland. This 23,000 acre estate hosts many wildlife species and engages in rewilding projects such as peatland and forest restoration, captive breeding of the Scottish wildcat, and reintroduction of the red squirrel. Visitors can engage in outdoor recreation and education programs.[118]

The British radio drama series The Archers featured rewilding areas in storylines in 2019 and 2020.[119][120]

The Netherlands

[edit]

In the 1980s, analogue species (Konik ponies, Heck cattle and red deer) were introduced to the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve, an area covering over 56 square kilometres (22 sq mi), in order to (re)create a grassland ecology by keeping the landscape open by naturalistic grazing.[121][122] This approach followed Vera's 'wood-pasture hypothesis' that grazing animals played a significant role in shaping European landscapes before the Neolithic period. Though not explicitly referred to as rewilding, many of the project's intentions were in line with those of rewilding. The case of the Oostvaardersplassen is considered controversial due to the lack of predators, and its management can be seen as having to contend with conflicting ideas regarding nature.[123]

Africa

[edit]In the 1990s and early 2000s, several multi-nation rewilding projects were suggested across Africa. Some notable examples are:

- The Tri-National de la Sangha, a plan focused on joining three national parks in Cameroon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Central African Republic. The goal was to restore a large area of rainforest to protect the region’s forest elephants, lowland gorillas, and the historical territory of the Ba’Aka pygmy people. [77]

- The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park, proposed to protect elephants by expanding South Africa’s largest national park, Kruger, and connecting it to Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park and Mozambique’s Coutada 16, a previous hunting concession. [77]

- The Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, conceived to join two existing parks in Botswana and South Africa, protecting the wildlife that relied on the region’s desert habitat. This park, spanning over 14,000 square miles, was officially established in 2000. [77]

- The Lubombo Transfrontier Conservation Area, designed to create a corridor for elephants through Mozambique, Eswatini, and South Africa. The reserve was formally established in 2000, and has been widely recognized for working with local communities and creating jobs in conservation. [77]

- The Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), the largest proposed wilderness reserve in the world, covering nearly 116,000 square miles. The project would connect thirty-six protected areas across five countries: Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. KAZA was conceived with two main goals in mind: protecting the largest population of elephants in the world, and conserving scarce water resources by sustainably managing the region’s wetlands. [77]

Namibia

[edit]In 1996, Namibia passed the Nature Conservation Act, a law that allowed communities of civilians to create their own protected wildlife conservancies to develop the country’s ecotourism sector. Conservancy creation was voluntary, but proved to be popular: by 2008, fifty-two conservancies were registered with the government, and fifteen more were seeking approval. [77] By this time, one in four rural Namibians were involved in conservation, and around fifteen percent of the country’s land was protected. Conservancy committees were tasked with hiring park guards and rangers to crack down on illegal hunting, in exchange for limited hunting rights for conservancy members. The Namibian government relocated locally extirpated species to these newly protected areas, and community members monitored their flourishing population sizes. [77]

One notable success of the Nature Conservation Act is Salambala, a conservancy established in 1998. The region, only 359 square miles large, went from having virtually no large game to boasting a population of elephants six hundred strong, a herd of fifteen hundred zebra, and three lion prides after twenty years. [77] Surveys conducted in the conservancy showed a 47 percent increase in wildlife sightings, just between 2004 and 2007. The local community was able to capitalize on the environmental success: by 2006, the community was earning thirty-seven times more revenue from tourism than they had been in 1998. [77]

Asia

[edit]Nepal

[edit]King Mahendra was crowned king of Nepal in 1955. An avid hunter, King Mahendra and his son instituted Nepal’s first Western-style national park, the Royal Chitwan National Park, in 1973. [77] Establishment of the park led to an increase in research being done on Nepal’s wildlife, including the Nepal Tiger Ecology Project, an eighteen-year-long field study conducted in Chitwan. Findings from this study convinced the Nepalese government to eventually enlarge the boundaries of Chitwan and join it with its neighboring Parsa and Valmiki wildlife reserves. In 1995, Nepal’s Parliament ratified bylaws that required 50 percent of the revenue from park entrance fees to go towards programs that would benefit local people, providing funding to build better schools and clinics and bolstering public support for parks. [77]

In 1993, Terai Arc Landscape Program (TAL) was started to restore forested corridors between Chitwan, other Nepalese parks like Bardia National Park and Parsa Wildlife Reserve, and Indian reserves along the countries’ shared border. TAL’s goal was to add “buffer zones” around the established parks and create pathways between them to facilitate the movement of large species like elephants, tigers, and rhino. [77] The project was initially successful, supporting over 600 endangered rhinos and attracting tens of thousands of tourists every year, but the success was disrupted by the Nepalese Civil War, which took place from 1996 to 2006. Hundreds of rhinos and tigers were killed during the war as a result of fewer park guards and governmental conservation groups growing disorganized by the war. By 2008, wildlife populations in the reserve began to grow again, but the war caused hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage to the project. [77]

Indonesia

[edit]In 2001, conservationist Willie Smits began buying land from a former palm oil plantation that has been ecologically destroyed by logging. He, along with a group of Dayak villagers in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province, replanted over twelve hundred species of trees on the land, which Smits renamed Samboja Lestari or “Everlasting Forest.” [77] The project’s hopes of returning the land to a tropical rainforest seems to be working: by 2009, temperature within the regrown forest had dropped by three to five degrees Celsius, humidity has risen by 10 percent, and rainfall had increased by 25 percent. 137 species of birds now reside on the land, up from only five species that had lived in the logged area. The replanted forest is also home to nine species of primates, as of 2009. [77]

See also

[edit]- Climate change mitigation effects of rewilding

- Environmental restoration

- Feral, a 2013 book about rewilding

- Great Green Wall (Africa)

- Involuntary park

- Natural landscape

- Permaculture

- Sea rewilding

- Species reintroduction

- Urban prairie

- Urban reforestation

- Urban rewilding

- Wildlife management

References

[edit]- ^ Sandom, Chris; Donlan, C. Josh; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Hansen, Dennis (15 April 2013), Macdonald, David W.; Willis, Katherine J. (eds.), "Rewilding", Key Topics in Conservation Biology 2 (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 430–451, doi:10.1002/9781118520178.ch23, ISBN 978-0-470-65876-5, retrieved 29 March 2024

- ^ a b c d e Carver, Steve; et al. (2021). "Guiding principles for rewilding". Conservation Biology. 35 (6): 1882–1893. Bibcode:2021ConBi..35.1882C. doi:10.1111/cobi.13730. PMID 33728690. S2CID 232263088.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian (December 2020). "Rewilding should be central to global restoration efforts". One Earth. 3 (6): 657–660. Bibcode:2020OEart...3..657S. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.014. ISSN 2590-3322.

- ^ Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; te Beest, Mariska; Kerley, Graham I. H.; Landman, Marietjie; le Roux, Elizabeth; Smith, Felisa A. (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding as a climate change mitigation strategy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170440. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0440. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231077. PMID 30348867.

- ^ Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; te Beest, Mariska; Kerley, Graham I. H.; Landman, Marietjie; le Roux, Elizabeth; Smith, Felisa A. (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding as a climate change mitigation strategy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170440. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0440. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231077. PMID 30348867.

- ^ Bakker, Elisabeth S.; Svenning, Jens-Christian (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding: impact on ecosystems under global change". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170432. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0432. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231072. PMID 30348876.

- ^ Lundgren, Erick J.; Ramp, Daniel; Ripple, William J.; Wallach, Arian D. (June 2018). "Introduced megafauna are rewilding the Anthropocene". Ecography. 41 (6): 857–866. Bibcode:2018Ecogr..41..857L. doi:10.1111/ecog.03430. ISSN 0906-7590.

- ^ Athumani, Paulo C.; Munishi, Linus K.; Ngondya, Issakwisa B. (January 2023). "Reconstructing Historical Distribution of Large Mammals and their Habitat to Inform Rewilding and Restoration in Central Tanzania". Tropical Conservation Science. 16: 194008292311668. doi:10.1177/19400829231166832. ISSN 1940-0829.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian (December 2020). "Rewilding should be central to global restoration efforts". One Earth. 3 (6): 657–660. Bibcode:2020OEart...3..657S. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.014.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (3 June 2021). "World must rewild on massive scale to heal nature and climate, says UN". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Jepson, Paul (18 May 2022). "The creative way to pay for wildlife recovery". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-051822-1. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Foote, Jennifer (5 February 1990). "Trying to Take Back the Planet". Newsweek.

- ^ Soulé, Michael; Noss, Reed (Fall 1998), "Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation" (PDF), Wild Earth, 8: 19–28, archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2023, retrieved 3 April 2023

- ^ Soule and Noss, "Rewilding and Biodiversity," p. 22.

- ^ Wolf, Christopher; Ripple, William J. (March 2018). "Rewilding the world's large carnivores". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (3): 172235. Bibcode:2018RSOS....572235W. doi:10.1098/rsos.172235. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5882739. PMID 29657815.

- ^ Sweeney, Oisín F.; Turnbull, John; Jones, Menna; Letnic, Mike; Newsome, Thomas M.; Sharp, Andy (August 2019). "An Australian perspective on rewilding". Conservation Biology. 33 (4): 812–820. Bibcode:2019ConBi..33..812S. doi:10.1111/cobi.13280. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 30693968.

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2009). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Picador. ISBN 978-0312655419.

- ^ Carver, Steve (2016). "Rewilding... conservation and conflict" (PDF). ECOS. 37 (2). Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Petersen, David (2005). "Book Review: Rewilding North America" (PDF). Bloomsbury Review. 25 (3). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ a b For more on the importance of predators, see William Stolzenburg, Where the Wild Things Were: Life, Death, and Ecological Wreckage in a Land of Vanishing Predators (New York: Bloomsbury, 2008).

- ^ MacArthur, Robert H.; Wilson, Edward O. (1967), The Theory of Island Biogeography, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- ^ Newmark, William D. (29 January 1987), "A Land-Bridge Island Perspective on Mammalian Extinctions in Western North American Parks", Nature, 325 (6103): 430–432, Bibcode:1987Natur.325..430N, doi:10.1038/325430a0, hdl:2027.42/62554, PMID 3808043, S2CID 4310316

- ^ Quammen, David (1996), The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions, New York: Simon & Schuster

- ^ Quammen, Song of the Dodo, pp. 443-446.

- ^ UNEP staffers (December 2019). "Rewilding London's urban spaces". United Nations Environment Programme. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Morss, Alex (24 February 2020). "The race to rewild". Ecohustler. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Pettorelli, Nathalie; Durant, Sarah M; du Toit, Johan T., eds. (2019). "Chapt. 1-3". Rewilding. Ecological Reviews. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108560962. ISBN 978-1-108-46012-5. S2CID 135134123. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Position Paper on "Ecosystem Restoration"" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization. October 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (3 June 2021). "World must rewild on massive scale to heal nature and climate, says UN". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Becoming #GenerationRestoration: Ecosystem Restoration for People, Nature and Climate" (PDF). United Nations. 3 June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Hawkins, Sally; et al. (June 2024). "Developing guidelines and a theory of change framework to inform rewilding application". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2024.1384267.

- ^ Carroll, Carlos; Noss, Reed F. (February 2021). "Rewilding in the face of climate change". Conservation Biology. 35 (1): 155–167. Bibcode:2021ConBi..35..155C. doi:10.1111/cobi.13531. ISSN 0888-8892. PMC 7984084. PMID 32557877.

- ^ Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; te Beest, Mariska; Kerley, Graham I. H.; Landman, Marietjie; le Roux, Elizabeth; Smith, Felisa A. (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding as a climate change mitigation strategy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170440. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0440. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231077. PMID 30348867.

- ^ Nogués-Bravo, David; Simberloff, Daniel; Rahbek, Carsten; Sanders, Nathan James (February 2016). "Rewilding is the new Pandora's box in conservation". Current Biology. 26 (3): R87 – R91. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..R87N. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.044. PMID 26859272. S2CID 739698.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian (December 2020). "Rewilding should be central to global restoration efforts". One Earth. 3 (6): 657–660. Bibcode:2020OEart...3..657S. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.014. S2CID 234537481.

- ^ Jarvie, Scott; Svenning, Jens-Christian (5 December 2018). "Using species distribution modelling to determine opportunities for trophic rewilding under future scenarios of climate change". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170446. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0446. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231076. PMID 30348873.

- ^ Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; te Beest, Mariska; Kerley, Graham I. H.; Landman, Marietjie; le Roux, Elizabeth; Smith, Felisa A. (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding as a climate change mitigation strategy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170440. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0440. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231077. PMID 30348867.

- ^ Malhi, Yadvinder; Lander, Tonya; le Roux, Elizabeth; Stevens, Nicola; Macias-Fauria, Marc; Wedding, Lisa; Girardin, Cécile; Kristensen, Jeppe Ågård; Sandom, Christopher J.; Evans, Tom D.; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Canney, Susan (February 2022). "The role of large wild animals in climate change mitigation and adaptation". Current Biology. 32 (4): R181 – R196. Bibcode:2022CBio...32.R181M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.01.041. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 35231416.

- ^ a b Schmitz, Oswald J.; Sylvén, Magnus; Atwood, Trisha B.; Bakker, Elisabeth S.; Berzaghi, Fabio; Brodie, Jedediah F.; Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; Davies, Andrew B.; Leroux, Shawn J.; Schepers, Frans J.; Smith, Felisa A.; Stark, Sari; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Tilker, Andrew; Ylänne, Henni (27 March 2023). "Trophic rewilding can expand natural climate solutions". Nature Climate Change. 13 (4): 324–333. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13..324S. doi:10.1038/s41558-023-01631-6. hdl:20.500.11755/f02184f8-911c-4efd-ac4e-d0882f666ebf. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 257777277. Archived from the original on 11 September 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Olofsson, Johan; Post, Eric (5 December 2018). "Effects of large herbivores on tundra vegetation in a changing climate, and implications for rewilding". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170437. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0437. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231078. PMID 30348880.

- ^ Schmitz, Oswald J.; Sylvén, Magnus (4 May 2023). "Animating the Carbon Cycle: How Wildlife Conservation Can Be a Key to Mitigate Climate Change". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 65 (3): 5–17. Bibcode:2023ESPSD..65c...5S. doi:10.1080/00139157.2023.2180269. ISSN 0013-9157.

- ^ Pringle, Robert M.; Abraham, Joel O.; Anderson, T. Michael; Coverdale, Tyler C.; Davies, Andrew B.; Dutton, Christopher L.; Gaylard, Angela; Goheen, Jacob R.; Holdo, Ricardo M.; Hutchinson, Matthew C.; Kimuyu, Duncan M.; Long, Ryan A.; Subalusky, Amanda L.; Veldhuis, Michiel P. (June 2023). "Impacts of large herbivores on terrestrial ecosystems". Current Biology. 33 (11): R584 – R610. Bibcode:2023CBio...33R.584P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.024. hdl:1887/3718719. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 37279691.

- ^ Olofsson, Johan; Post, Eric (5 December 2018). "Effects of large herbivores on tundra vegetation in a changing climate, and implications for rewilding". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170437. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0437. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231078. PMID 30348880.

- ^ Sobral, Mar; Silvius, Kirsten M.; Overman, Han; Oliveira, Luiz F. B.; Raab, Ted K.; Fragoso, José M. V. (9 October 2017). "Mammal diversity influences the carbon cycle through trophic interactions in the Amazon". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (11): 1670–1676. Bibcode:2017NatEE...1.1670S. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0334-0. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 28993614. S2CID 256704162. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; te Beest, Mariska; Kerley, Graham I. H.; Landman, Marietjie; le Roux, Elizabeth; Smith, Felisa A. (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding as a climate change mitigation strategy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170440. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0440. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231077. PMID 30348867.

- ^ Kimbrough, Liz (30 March 2023). "Rewilding animals could be key for climate: Report". Mongabay Environmental News. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "What is rewilding and how is it relevant to climate change?". Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ Salter, Eleanor (28 May 2022). "Rewilding, or just a greenwashed land grab? It all depends on who benefits". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ "Rewilding glossary". Rewilding Britain. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b Sandom, Christopher J.; Dempsey, Benedict; Bullock, David; Ely, Adrian; Jepson, Paul; Jimenez-Wisler, Stefan; Newton, Adrian; Pettorelli, Nathalie; Senior, Rebecca A. (16 October 2018). "Rewilding in the English uplands: Policy and practice". Journal of Applied Ecology. 56 (2): 266–273. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13276. ISSN 0021-8901. S2CID 91608488.

- ^ Gillson L, Ladle RJ, Araújo MB. 2011. Baselines, patterns and process. In: Ladle RJ, Whittaker RJ, Eds. Conservation biogeography. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444390001.ch3

- ^ Navarro, Laetitia M.; Pereira, Henrique M. (1 September 2012). "Rewilding Abandoned Landscapes in Europe". Ecosystems. 15 (6): 900–912. Bibcode:2012Ecosy..15..900N. doi:10.1007/s10021-012-9558-7. ISSN 1435-0629. S2CID 254079068.

- ^ Carver, Steve (2016). "Rewilding... conservation and conflict" (PDF). ECOS. 37 (2). Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Toit, Johan T.; Pettorelli, Nathalie (2019). "The differences between rewilding and restoring an ecologically degraded landscape". Journal of Applied Ecology. 56 (11) (published 16 August 2019): 2467–2471. Bibcode:2019JApEc..56.2467D. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13487. ISSN 0021-8901. S2CID 202025350.

- ^ Galetti, M. (2004). "Parks of the Pleistocene: Recreating the cerrado and the Pantanal with megafauna". Natureza e Conservação. 2 (1): 93–100.

- ^ Donlan, C.J.; et al. (2006). "Pleistocene Rewilding: An Optimistic Agenda for Twenty-First Century Conservation" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 168 (5): 1–22. doi:10.1086/508027. PMID 17080364. S2CID 15521107. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian; Pedersen, Pil B. M.; Donlan, C. Josh; Ejrnæs, Rasmus; Faurby, Søren; Galetti, Mauro; Hansen, Dennis M.; Sandel, Brody; Sandom, Christopher J.; Terborgh, John W.; Vera, Frans W. M. (26 January 2016). "Science for a wilder Anthropocene: Synthesis and future directions for trophic rewilding research". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4): 898–906. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..898S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502556112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4743824. PMID 26504218.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian; Buitenwerf, Robert; Le Roux, Elizabeth (6 May 2024). "Review: Trophic rewilding as a restoration approach under emerging novel biosphere conditions". Current Biology. 34 (9): R435 – R451. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2024.02.044. PMID 38714176.

- ^ "C40 Knowledge Community". www.c40knowledgehub.org. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Wright, Justin P.; Jones, Clive G.; Flecker, Alexander S. (1 June 2002). "An ecosystem engineer, the beaver, increases species richness at the landscape scale". Oecologia. 132 (1): 96–101. Bibcode:2002Oecol.132...96W. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-0929-1. ISSN 1432-1939. PMID 28547281.

- ^ a b "European Bison bonasus Through grazing, foraging, wallowing and trampling, the hefty bison boosts habitat diversification". Rewilding Britain. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Sandom, Christopher J; Hughes, Joelene; Macdonald, David W (2012). "Rooting for rewilding: quantifying wild boar's Sus scrofa rooting rate in the Scottish Highlands". Restoration Ecology. 21 (3): 329–335. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.2012.00904.x. S2CID 82475098. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ MacDonald, Benedict (2019). Rebirding (2020 ed.). Exeter, U.K.: Pelagic. pp. 16–17, 25, 87–88, 201, 214, 248, plate 30. ISBN 978-1-78427-219-7.

- ^ Jackowiak, Mateusz; Busher, Peter; Krauze-Gryz, Dagny (8 August 2020). "Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) Winter Foraging Preferences in Northern Poland—The Role of Woody Vegetation Composition and Anthropopression Level". Animals. 10 (8): 1376. doi:10.3390/ani10081376. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 7460282. PMID 32784368.

- ^ Keulartz, Jozef (1 April 2009). "Boundary Work in Ecological Restoration". Environmental Philosophy. 6 (1): 35–55. doi:10.5840/envirophil2009613.

- ^ Fløjgaard, Camilla; Pedersen, Pil Birkefeldt Møller; Sandom, Christopher J.; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Ejrnæs, Rasmus (January 2022). "Exploring a natural baseline for large-herbivore biomass in ecological restoration". Journal of Applied Ecology. 59 (1): 18–24. Bibcode:2022JApEc..59...18F. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.14047. ISSN 0021-8901. S2CID 243489626.

- ^ Mduma, Simon A. R.; Sinclair, A. R. E.; Hilborn, Ray (November 1999). "Food regulates the Serengeti wildebeest: a 40-year record". Journal of Animal Ecology. 68 (6): 1101–1122. Bibcode:1999JAnEc..68.1101M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00352.x. ISSN 0021-8790.

- ^ MacDonald, Benedict (2019). Rebirding (2020 ed.). Exeter, U.K.: Pelagic. pp. 153, 155–156, 180–188, 204. ISBN 978-1-78427-219-7.

- ^ Jamieson, Dale (2008). "The Rights of Animals and the Demands of Nature". Environmental Values. 17 (2): 181–200. doi:10.3197/096327108X303846. JSTOR 30302637. S2CID 144642929.

- ^ von Essen, Erica; Allen, Michael (29 September 2015). "Wild-But-Not-Too-Wild Animals: Challenging Goldilocks Standards in Rewilding". Between the Species. 19 (1). Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Moen, Ole Martin (9 May 2016). "The ethics of wild animal suffering". Etikk I Praksis. 10 (1): 91–104. doi:10.5324/eip.v10i1.1972.

- ^ Jørgensen, Dolly (October 2015). "Rethinking rewilding". Geoforum. 65: 482–488. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.016.

- ^ Prior, Jonathan; Ward, Kim J. (February 2016). "Rethinking rewilding: A response to Jørgensen" (PDF). Geoforum. 69: 132–135. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.12.003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b Barkham, Patrick (3 April 2017). "'It is strange to see the British struggling with the beaver': why is rewilding so controversial?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Sheep farmers attack new attempt to reintroduce lynx". FarmingUK. 1 February 2021. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Middleton, Amy (14 February 2016). "Rewilding may be death sentence to other animals". Cosmos Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Fraser, Caroline (2009). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Picador. ISBN 978-0312655419.

- ^ Giuffrida, Angela (17 November 2024). "How a fatal bear attack led an Italian commune to rally against rewilding". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 November 2024.

- ^ Lerwill, Ben (1 May 2024). "Northern Italy's 'problem bears' show the challenges of rewilding carnivores". National Geographic. Retrieved 17 November 2024.

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2009), Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution, New York: Metropolitan Books, pp. 32–35, 79–84, 119–128, 203–240, 326–330, 303–312

- ^ a b Manning, Richard (2009), Rewilding the West: Restoration in a Prairie Landscape, Berkeley: University of California Press

- ^ Determan, Amanda (5 December 2024). "American Prairie surpasses half a million acres". American Prairie. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ Blumm, Michael C.; Erickson, Andrew B. (2012). "Dam Removal in the Pacific Northwest: Lessons for the Nation". Environmental Law. 42 (4): 1043–1100. JSTOR 43267821. SSRN 2101448.

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2009). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Picador. ISBN 978-0312655419.

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2009). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Picador. ISBN 978-0312655419.

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2009). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution. Picador. ISBN 978-0312655419.

- ^ Belen Filgueira (March 2022). "La ciencia detrás del rewilding, la estrategia de restauración biológica que revoluciona la conservación de la naturaleza". Infobae. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Fernandez, Fernando A. S.; Rheingantz, Marcelo L.; Genes, Luísa; Kenup, Caio F.; Galliez, Maron; Cezimbra, Tomaz; Cid, Bruno; Macedo, Leandro; Araujo, Bernardo B. A.; Moraes, Bruno S.; Monjeau, Adrian (1 October 2017). "Rewilding the Atlantic Forest: Restoring the fauna and ecological interactions of a protected area". Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. 15 (4): 308–314. Bibcode:2017PEcoC..15..308F. doi:10.1016/j.pecon.2017.09.004. hdl:11336/70388. ISSN 2530-0644.

- ^ Marjakangas, Emma-Liina; Genes, Luísa; Pires, Mathias M.; Fernandez, Fernando A. S.; de Lima, Renato A. F.; de Oliveira, Alexandre A.; Ovaskainen, Otso; Pires, Alexandra S.; Prado, Paulo I.; Galetti, Mauro (5 December 2018). "Estimating interaction credit for trophic rewilding in tropical forests". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170435. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0435. PMC 6231069. PMID 30348879.

- ^ a b Oliver, Megan (8 March 2023). "Tasmania 'vital location' in 'rewilding' efforts to rebuild native animal populations". ABC News (Australia). Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Rewilding Australia". WWF-Australia. Retrieved 14 April 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Foundation » Rewilding Europe A new beginning. For wildlife. For us". www.rewildingeurope.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- ^ "The comeback of the European icon". RewildingEurope.com. 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Reviving Europe, archived from the original on 28 November 2019, retrieved 29 May 2018

- ^ "Kernzonen". Biosphärenpark Wienerwald. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Boyd Tonkin (17 July 2015). "'Rewilding' would create a theme park, not a return to nature". The Independent. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "At Rewilding Britain, we believe in these five principles for rewilding. We ask network members to confirm that their project is in line with these principles"[1] Archived 5 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Defining rewilding". Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Pleistocene occurrences of the European pond tortoise (Emys orbicularis L.) in Britain | Request PDF". ResearchGate. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Gleed-Owen, Chris Paul (March 2000). "Subfossil records of Rana cf. lessonae, Rana arvalis and Rana cf. dalmatina from Middle Saxon (c. 600-950 AD) deposits in eastern England: Evidence for native status". Amphibia-Reptillia. 21: 57–65. doi:10.1163/156853800507273 – via Research Gate.

- ^ "'Who doesn't love a turtle?' The teenage boys on a mission – to rewild Britain with reptiles". The Guardian. 10 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Guest blog by Celtic Reptile and Amphibian - Mark Avery". markavery.info. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Horton, Helena (6 April 2021). "Frog turns blue for first time in 700 years amid calls for rare amphibians to be reintroduced to Britain". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Davis, Margaret (7 April 2021). "Blue Moor Frog Once Again Seen in the UK After 700 Years in Time for Mating Season". Science Times. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Barkham, Patrick (7 July 2023). "European pond turtle could return to British rivers and lakes". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Melissa Harrison (21 November 2020). "From rewilding to forest schools, our attitude to nature is changing for the better". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Stephen Moss (21 November 2020). "Missing lynx: how rewilding Britain could restore its natural balance". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Virginia (2022). "Domesticating Rewilding: Interpreting Rewilding in England's Green and Pleasant Land". Environmental Values. 31 (5): 515–532. doi:10.3197/096327121x16328186623841. hdl:10871/127170. S2CID 244335279. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "The project is not promoted as rewilding due to local sensitivities around the term, but as a nature restoration project it has similarities to other projects in the Network" [2] Archived 29 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Rewilding revives a country estate". Financial Times. 28 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Looking at rewilding at Knepp. Alastair Driver of Rewilding Britain discusses the process of rewilding, and talks about trees, timber and tree planting. Filmed at Knepp in the summer of 2021", video by woodforthetrees.uk, 2021 [3] Archived 29 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Further reading: Isabella Tree, Wilding: The return of Nature to a British Farm, charting her rewilding project at Knepp

- ^ Tree, Isabella. "Rewilding in West Sussex". Knepp Wildland. Knepp Castle Estates. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Storks are back in Britain – and they're a beacon of hope for all of us | Isabella Tree". The Guardian. 8 July 2019. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Broughton Sanctuary". Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Nature Recovery FAQs". Broughton Hall, North Yorkshire. 2021. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "In this first episode of Rewilding Mapperton, Luke describes his plans to allow nature to take over at Coltleigh Farm, and how Mapperton has been inspired by the pioneering Knepp Estate in Sussex", 2021 [4] Archived 29 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Home - Alladale". 18 November 2022. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Restoring Nature and Climate Change". Hansard. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ "Synopses for 2020". ambridgereporter.org.uk. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Cossins, Daniel (1 May 2014). "Where the Wild Things Were". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (24 December 2012). "Dept. of Ecology: Recall of the Wild". The New Yorker. pp. 50–60. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Buurmans, Meghan Debating the ‘wild’: What the Oostvaardersplassen can tell us about Dutch constructions of nature. (2021) https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1523877/FULLTEXT01.pdf Archived 14 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 29 September 2023

Further reading

[edit]- van der Land, Hans and Poortinga, Gerben (1986). Natuurbos in Nederland: een uitdaging, Instituut voor Natuurbeschermingseducatie. ISBN 90-70168-09-x (in Dutch)

- Foreman, Dave (2004). Rewilding North America: A Vision for Conservation in the 21st Century, Island Press. ISBN 978-1-55963-061-0

- Fraser, Caroline (2010). Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution, Picador. ISBN 978-0-312-65541-9

- Hawkins, Convery, Carver & Beyers, eds. (2023). Routledge Handbook of Rewilding, Routledge.

- Jepson, Paul and Blythe, Cain (2022). Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery (The Illustrated Edition), The MIT Press.

- MacKinnon, James Bernard (2013). The Once and Future World: Nature As It Was, As It Is, As It Could Be, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-10305-4

- Monbiot, George (2013). Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-197558-0

- Monbiot, George (2022). Regenesis: Feeding the World without Devouring the Planet, Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-313596-8

- Louys, Julien et al. (2014). "Rewilding the tropics, and other conservation translocations strategies in the tropical Asia-Pacific region". doi:10.1002/ece3.1287

- Root-Bernstein, Meredith et al. (2017) "Rewilding South America: Ten key questions". doi:10.1016/j.pecon.2017.09.007

- Pereira, Henrique M., & Navarro, Laetitia (2015). Rewilding European Landscapes, Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-12038-6

- Pettorelli, Durant & du Troit, eds. (2019). Rewilding, Cambridge University Press.

- Tree, Isabella (2018), Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm, Picador, ISBN 978-1-5098-0511-2

- Wilson, Edward Osborne (2017). Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life, Liveright (W.W. Norton). ISBN 978-1-63149-252-5

- Wright, Susan (2018). SCOTLAND: A Rewilding Journey, Wild Media Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9568423-3-6

- Thulin, Carl-Gustaf, & Röcklinsberg, Helena (2020). "Ethical Considerations for Wildlife Reintroductions and Rewilding". doi:10.3389/fvets.2020.00163

External links

[edit]Projects

[edit]This section's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (September 2024) |

- American Prairie Reserve

- Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, Costa Rica

- European Green Belt

- European Wildlife - European Centre of Biodiversity

- Gondwana Link

- Heal Rewilding

- Highlands Rewilding

- Lewa Wildlife Conservancy

- Peace Parks Foundation

- Pleistocene Park

- Rewilding Britain

- Rewilding Europe

- Rewilding Australia

- Rewilding Institute

- Self-willed land

- Scotland: The Big Picture

- Terai Arc Landscape Project (WWF)

- Wildland Network UK

- Wildlands Network N. America (formerly Wildlands project)

- Wisentgrazing-project, Holland

Information

[edit]- Book on experimental methods to rewild forests with grazers and dead and decaying wood

- an docu-film about the reintroduction of wild horses 15 years after

- Rewilding the World: Dispatches from the Conservation Revolution

- "Rewilding the World: A Bright Spot for Biodiversity"

- Rewilding and Biodiversity: Complementary Goals for Continental Conservation, Michael Soulé & Reed Noss, Wild Earth, Wildlands Project Fall 1998

- Stolzenburg, William (2006). "Where the Wild Things Were". Conservation in Practice. 7 (1): 28–34. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4629.2006.tb00148.x. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- "For more wonder, rewild the world", George Monbiot's July 2013 TED talk

- Bengal Tiger relocated to Sariska from Ranthambore | Times of India