Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2011 September 15

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < September 14 | << Aug | September | Oct >> | September 16 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

September 15

[edit]Han Solo

[edit]Is it possible to survive being completely frozen in a block of dry ice? 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:08, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Han Solo wasn't frozen in a block of dry ice. --Elen of the Roads (talk) 00:12, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- No, at least not without some preparations which don't currently exist, since anti-freeze would be needed in every cell to prevent ice crystal formation, which tears the cells apart. BTW, I thought he was frozen in some kind of metal, not ice. StuRat (talk) 00:14, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- He was frozen in carbonite, which I expect would be similar to dry ice. Anyway it's clear from the dialogue between Darth Vader and the other Imperial characters present that extreme low temperatures are involved in the process. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:19, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- It says that carbonite is a "cryonic alloy", which confirms the use of extreme low temperatures. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:21, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and a human body presumably can exist in suspended animation for quite some time at cryogenic temperatures, but the question is how to get it from normal temperature to frozen, and how to thaw it out, without causing extensive damage. StuRat (talk) 00:31, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I take this answer to mean "not survivable". 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:47, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Not with current technology, no. StuRat (talk) 01:06, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Keep in mind this was a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, where they had developed faster-than-light speed, swords made of light, telekinesis, etc., so it's reasonable to suppose they might have developed survivable cryogenics as well. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 01:05, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Cryonics is our article on this. (Minus the fictional "carbonite" substance from the Star Wars universe.) Comet Tuttle (talk) 00:57, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- And vitrification discusses the general problem of freezing without ice crystal damage, which is relevant to organ preservation for transplantation as well as some bulk food preservation. For example, soybeans in Japan (edamame) are worth much more if they do not have the mushy texture from cell wall damage resulting from ordinary freezing, but fresh soybeans will spoil. That's why the Japanese have the most advanced vitrification freezers at present.[1][2] However, mammilian studies of cryonics have been suspended for the reasons stated in Smith, A.U. (1957) "Problems in the Resuscitation of Mammals from Body Temperatures Below 0°C" Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 147(929):533-544 (14 pages), which states: "Two of the galagos regurgitated and inhaled bicarbonate from the stomach during administration of artificial respiration. The other two galagos which had been treated with bicarbonate and then frozen for 45 minutes seemed to make an excellent recovery after thawing. One of them regained an appetite as well as normal posture and behaviour. Within 24 hours they both died. At post mortem the stomach was normal, but in one animal the duodenum and jejunum contained bloodstained fluid. In both instances there was oedema of the lungs and froth in the trachea. This may have been a terminal event. Survival may have been limited by some other physico-chemical or physiological derangement which, if diagnosed, might well have been susceptible to treatment. It was therefore decided to postpone further experiments on freezing the larger mammals until the effects on other organs of freezing in vivo and in vitro were better understood." (page 538.) Figure 60 on Plate 25 is captioned: "A frozen galago is being rewarmed with diathermy. It lies inside a Perspex tube surrounded by the output coil of the diathermy apparatus. Artificial respiration is being given by insufflating air into a tracheal cannula."

- I expect mammalian studies to continue when vitrification freezers are capable of vitrifying several kilograms at a time; they are almost there. 70.91.171.54 (talk) 02:09, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Also note that dry ice isn't all that cold. If you did manage to freeze a body, you'd want to keep it as cold as possible, to prevent decay. You would therefore at least use liquid nitrogen. StuRat (talk) 01:08, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- For completeness' sake, shall we stipulate that the question assumes we are discussing actual biology here on Earth, and that the reference to the Star Wars character is merely a colorful metaphor? If instead the question is about scientifically plausible exobiologies, then most bets are off. I imagine that such extraterrestrial life forms, if they are to achieve much complexity, would be built up of something analogous to our cells, but there's no reason to assume a priori that they'd necessarily contain a lot of water, or that their membranes would necessarily be susceptible to rupture due to the expansion of that water in freezing. Indeed, now that I think of it, there might be (cryophilic) extremophiles right here on Earth who withstand freeze-thaw cycles perfectly well; but we mammals aren't among them.—PaulTanenbaum (talk) 01:24, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- See also Water bear. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 01:29, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Wasn't part of the story that carbonite was NOT used to freeze people, only cargo? So even in the movie, freezing Han was a big risk. That doesn't change the discussion, I just mean that it wasn't like a normal "run of the mill" thing they did to people. Vespine (talk) 03:31, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- That particular equipment was only used for cargo. They don't mention if the technology in general is used on humans. I figure it must be done from time to time in the Star Wars universe, since everyone seemed to know so much about the process. APL (talk) 06:02, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Right, the whole point of freezing Han Solo was to test out the machinery to make sure that it wouldn't damage the intended subject -- Luke Skywalker. --- Medical geneticist (talk) 13:02, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- That particular equipment was only used for cargo. They don't mention if the technology in general is used on humans. I figure it must be done from time to time in the Star Wars universe, since everyone seemed to know so much about the process. APL (talk) 06:02, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Wasn't part of the story that carbonite was NOT used to freeze people, only cargo? So even in the movie, freezing Han was a big risk. That doesn't change the discussion, I just mean that it wasn't like a normal "run of the mill" thing they did to people. Vespine (talk) 03:31, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- See also Water bear. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 01:29, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

Old HDTVs and broadcast DTV in the US

[edit]Confused I am about the "new" digital TV broadcasting in the US, after having read Digital television transition in the United States, and having read this US government FAQ page. Question 1: The latter link seems to claim that all television sets that say "HDTV" contain digital tuners and can receive the new digital broadcasts. But what about old HDTVs from the early 2000s? Surely their tuners don't know about the digital spectrum range that is now in use. For example, Samsung's LN-R238W is an HDTV that seems to date from 2005; it is new enough to have an HDMI input, so it certainly can accept digital input; but it's sufficiently old that I don't think its internal tuner could be digital. Is that US government FAQ just misleading and wrong? Question 2: What TV format is broadcast now in the US? Is it a 1080p signal? 720p? Is every channel different? How does this comport with the amount of spectrum reserved for each station? (Our Digital television in the United States article is frustratingly vague about today's exact broadcast situation.) Comet Tuttle (talk) 01:11, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The current US digital broadcast frequencies and formats were standardized in the early 1990s, mostly at MIT with the participation of a wide consortium of TV set vendors, but I don't know the names of the standards. 70.91.171.54 (talk) 02:17, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Both 1080i and 720p are now broadcast in the US, and require similar bandwidth, but not 1080p, which requires considerably more. Some sub-channels are 1080i and some are 720p. It would be better if they could change the format of one sub-channel between the two, based on the type of program they wish to broadcast (fast action needs 720p, while slow programs benefit from 1080i), but they don't seem to do that. There may be a technical problem with doing that, such as if the digital tuner only determines the format when you first tune to that sub-channel.

- Another option is to have one sub-channel in the one format, and another sub-channel in the other format, both with the same content. We had that in Detroit, with channels 2.1 and 2.2, but they then dropped 2.2. Apparently the cost of broadcasting in both formats outweighed the benefit. StuRat (talk) 03:39, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- As the former owner of an early 2000s CRT HDTV, I can tell you that it did not have an internal tuner and was not, technically, an HDTV. On the front, it said "HD Monitor". gnfnrf (talk) 17:18, 20 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, there was a great deal of deception at that time, as makers of TVs without HD tuners found they wouldn't sell unless they implied that they did contain HD tuners. StuRat (talk) 17:22, 20 September 2011 (UTC)

- Just to be clear; I was not personally deceived, either by the packaging or the salespeople. I knew my "TV" would not receive broadcast signals. In fact, they tried to sell me a tremendously expensive tuner to add that capability. I didn't mind, however, because a tuner is only required for broadcast signals. Cable TV, DVD/Blu-Ray, and video games all work just fine. gnfnrf (talk) 19:28, 20 September 2011 (UTC)

Name of a phobia?

[edit]I have an intense fear of chemicals–to be specific, I fear man-made/synthetic chemicals. I also fear things like Clorox wipes , and a lot of products I use are made from plants or are home-made. Is there a name of a phobia for this? HurricaneFan25 01:12, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Concur -- chemophobia is the correct name. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 01:16, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I agree the above answers the question, I think another article which is related and may be of interest is Naturalistic fallacy. Vespine (talk) 01:21, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- How can you possibly distinguish between synthetic and naturally occuring chemicals? For instance, you have a bottle of a vanillin extracted from vanilla pods, and next to it there is another bottle of synthesised vanillin. How could you possibly know which is which? Plasmic Physics (talk) 01:56, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Exactly -- you can't, not even with the latest analytical methods. That's because they're the exact same substance. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 02:14, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Guys, phobias are not rational. You can't make them go away by explaining to the phobic why their fears don't make any sense. If it could be explained away, it wouldn't be a phobia. --Jayron32 02:22, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- No, but we can try to understand them better. The point others made above is that it's impossible to tell whether some chemicals are man-made or not, so I too want to know how the OP thinks he can tell. HiLo48 (talk) 02:42, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Scotsmen, for example, wear kilts because they have pantophobia. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 02:27, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- No that's because sheep can hear zips. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:51, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Scotsmen, for example, wear kilts because they have pantophobia. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 02:27, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- That fearsome Chlorox? Bleach is made from sea salt. I'm actually surprised they don't market it as such. DMacks (talk) 02:24, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Of course, naming phobias is more of a parlor game than anything else. Except for a few very common ones, doctors tend to just write "phobia of chemicals" rather than bother with a specific name that no one knows anyway. APL (talk) 02:24, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The Martians that lived on its larger moon feared only fear itself. They had Phobos phobo phobia. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 02:30, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- So what would be the name of a phobia of very tall objects? I used to have a variation of this (a specific phobia of power-line towers), but have been cured. I'm just curious to know what's it called. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 02:28, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm thinking "polephobia". I'm more curious to know how you got cured. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 02:31, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- According to List of phobias and other sites I found in google, it sounds like "batophobia". ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 02:35, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Re. your question to me: I don't remember, since it was a while ago. But AFAIR this was close to the time that I started doing research for my first writing project (a detective novel in which the Paki intelligence service sets off an EMP device in LA, which I unfortunately had to abandon with only a couple chapters written), and this research required me to spend quite a lot of time around electrical substations and other high-voltage eyesores, so this might have something to do with it. Maybe this need to do research gave me the motivation to try to overcome my fear? 67.169.177.176 (talk) 03:40, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Jayron: I was just trying to clear up some confusion, how does he know to identify what he fears; if he can't tell them apart, does he fear both or neither. Plasmic Physics (talk) 02:42, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- There's no big mystery. Even if you fear something obvious like spiders you don't feel fear if you don't know a spider is present. (Which is probably the majority of the time, given how well they hide.) It's not about scientifically determining if the thing you fear is present, it's about whether or not you think it's present. APL (talk) 02:57, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Lots of folks are afraid of various things, but they're only phobias if they're (1) unreasonable and (2) disabling in some way. It's easy to be startled by a spider or a snake, but then you get your composure and deal with it - unless you have a true phobia, in which case you do the sensible thing: panic, take drugs, and call an Orkin team. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 03:06, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- APL: The scenario is that you know there is a man-made chemical present, you just don't know which one it is. Plasmic Physics (talk) 03:23, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- On a side note, there are phobias like a fear of wearing a pair missmatched socks, or a fear of non-round shaped buttons. Plasmic Physics (talk) 03:29, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I don't think a fear of artificially created chemicals is all that unreasonable. The reason is that scientists create them and then they add them to our food, etc., with insufficient testing. To give just one example, naturally occurring trans fats were rare and not a health problem, then scientist learned how to create them, and put large quantities in our foods, oblivious to the health danger that entailed. StuRat (talk) 03:56, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- They put Clorox in foods??? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 03:59, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Actually, I believe that bleach is used in various food processing steps, but hopefully most of it is removed from the final product. StuRat (talk) 04:21, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- For example, white bread Jebus989✰ 10:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- They don't use CLOROX in white bread -- they use chlorine dioxide, which COMPLETELY EVAPORATES from the flour WELL BEFORE baking! Do you not know the difference, or are you purposely conflating the two? 67.169.177.176 (talk) 04:40, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Of course not, we were talking about using bleach in food processing. I didn't mention chlorox at all Jebus989✰ 08:20, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- The term "bleach" specifically refers to hypochlorite salts. Chlorine dioxide is not a hypochlorite, so calling it "bleach" is wrong. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:27, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- Bleach is any chemical which tends to remove color, as our article states. In fact, it specifically mentions chlorine dioxide at the top of the "Other Examples" section. StuRat (talk) 04:44, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- In colloquial usage, not in the context of professional chemistry. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 03:25, 18 September 2011 (UTC)

- Professional chemists would tend to use the scientific name of the chemical, not an ambiguous term like "bleach". StuRat (talk) 19:34, 18 September 2011 (UTC)

- Only in China. As far as trans fats in food are concerned, those are NOT intentionally created, nor intentionally added to the food, but are formed as an UNINTENTIONAL byproduct during the hydrogenation of vegetable fats to produce margarine. Modern methods for margarine production are designed to reduce the formation of trans-fats as much as possible through accurate process control (which they hadn't bothered with until after the health effects of trans-fats became known). 67.169.177.176 (talk) 04:19, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Our trans fat article say "Trans fats are used in shortenings for deep-frying in restaurants, as they can be used for longer than most conventional oils before becoming rancid". That sounds like the intentional use of trans fats. Is our article wrong ? StuRat (talk) 04:28, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Used to be, perhaps. The same article also says that many US restaurants are phasing them out in favor of other substitutes. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 04:40, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Some are, some aren't. White castle still has 14 grams in their 20 chicken rings and 13 grams in their 10 cheese sticks (both outside of New Jersey): [3]. And none of this takes away from my argument that new chemicals (or, in this case, a new way to create an old chemical) do present a danger. StuRat (talk) 15:08, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- No, StuRat, rational skepticism is a good thing; which is quite different than a phobia. The two concepts are completely unrelated. If a spider falls onto my back where I cannot see it, it is a reasonable survival instinct to freak out a little bit as I try to get it off me. However, people with a true phobia of spiders become paralyzed with fear in irrational ways; like seeing photographs of spiders which they know are photographs, or having people talk about spiders around them, etc. Being rationally wary of food additives is a good thing, and likely to be good for your health. Having panic attacks every time you come into contact with something which may or may not be a "man made chemical" (without even any understanding of what that means or how to identify them) is a different matter entirely. --Jayron32 04:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yeah, but I'm saying: man-made chemicals do not always have a lable that says "Hey, over here! Look at me! I'm synthetic!" It isn't always black and white. Plasmic Physics (talk) 07:20, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I believe it's quite the contrary: most of the time this will be explicitly NOT stated. --Ouro (blah blah) 10:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- It doesn't matter whether something is natural or synthetic (e.g. baking soda made from trona ore vs. made synthetically by the Solvay process, or natural vanillin vs. synthetic); what DOES matter is whether something is harmful (trans fats, marijuana, etc.) or not (dihydrogen monoxide, ascorbic acid, carotene, etc.) 67.169.177.176 (talk) 02:17, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- However, newly synthesized chemicals (or old chemicals created by a new process) should be treated as if they are dangerous, until extensive safety testing is done on them, especially if the intent it to take them internally. The little testing which is done on such chemicals seems rather inadequate, to me, so I'd say they should be treated as dangerous for several decades, until the dangers would become obvious. For example, it was some 80 years after the introduction of aspirin that one of it's potentially fatal side effects, Reye's syndrome, was discovered. StuRat (talk) 05:02, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- That's what the FDA is for -- to test new foods and medicines for any dangerous health effects. As for "treating them as dangerous for several decades", this will (1) cause many times more deaths and suffering from the lack of medicines to treat dangerous diseases than would be the case in the worst-possible scenario for adverse effects under current testing laws, and (2) completely thwart ANY new medical research (because it would take several DECADES for it to even START paying off), thus further compounding the problem. We're ALREADY seeing this with the high costs and time delays of clinical testing discouraging pharmaceutical companies from developing new medicines (including some that could potentially cure lethal diseases such as cancer and even AIDS). To place further barriers in the way of medical research, as you have just proposed, would condemn MILLIONS of cancer sufferers and other sick people to die from lack of medicine for their condition, and would in fact be tantamount to legislative mass murder. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 05:57, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Settle down. For foods, the long wait always makes sense, but for meds we need to do a "cost-risk" analysis. If the new med has no apparent benefits over existing meds, or isn't for any life-threatening condition, then the long wait makes sense there. If somebody actually comes up with the proverbial "cure for cancer", then a great deal of risk would be justified. StuRat (talk) 06:47, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- That's more like it. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:28, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- Interesting that you mention aspirin as an example of a "dangerous newly-synthesized chemical", since that's simply synthetic willow-bark extract. --Carnildo (talk) 23:48, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- I also said "or old chemicals created by a new process". These can present a danger in many ways:

- A) It may not be quite the same as the natural chemical. A portion could be some type of isomer, for example, which doesn't occur in that ratio in the natural version.

- B) There could be impurities left in from the manufacturing process, or a missing co-ingredient present in the natural form.

- B) Manufacturing may allow the chemical to be used in large quantities, posing new hazards not present when the small amounts which naturally occur were used. This is likely the case with Reye's Syndrome, as it would probably take more willow-bark tea to get this effect than anyone was likely to consume. StuRat (talk) 18:15, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- I want to know, how he decides if something is natural or synthetic. On what basis does he decide whether he should be phobic or not of a particular chemical, if it's not labled as such? Plasmic Physics (talk) 09:47, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I think you're over analysing this. Presumably, a liquid in a plastic bottle marked "Heavy duty toilet bleach" would be feared, while an injured plant leaking sap would not. It's fairly obvious the OP is not professing a sixth-sense whereby they can determine the synthetic process used to create any given chemical he sees Jebus989✰ 10:12, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- One thing to note is that he mentioned products made from plants not plant material. I think you're missing the point, how does he decide for less obvious products? Plasmic Physics (talk) 10:36, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I can only speculate HurricaneFan has developed some means of distinguishing "Organic aloe vera 100% natural cleansing solution" in a health shop from a bottle of "industrial extra-strength bleach" in Tescos Jebus989✰ 10:45, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- There you go, obvious labling. On a side note, I've seen organic salt sold on the shelves. Yes, it was NaCl. Plasmic Physics (talk) 10:57, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm curious to know how the OP managed to post this question without coming into contact with the evil man-made chemical synthetic plastic computer keyboard? Warning! This poster may contain dihydrogen monoxide. Roger (talk) 12:02, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- One has to distinguish between phobias and misunderstandings. Education can clear up misunderstandings. What is initially labeled a phobia might not be that at all. We should not be so quick to pigeonhole fears as irrational. There can in fact be a grey area in which an aversion to a certain stimuli is partially rational, partially irrational, and partially amenable to modification via education. Bus stop (talk) 12:10, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Plasmic, you're still missing the point entirely. It absolutely and completely doesn't matter one iota if the phobic can definitively say that some substance or another is manmade, for the purpose of having the phobia. A person my have a phobia against apple juice. Maybe they scream and cry like a baby whenever they see a Volkswagen because they think that Volkswagens contain apple juice. It actually doesn't matter that a) Volkswagens don't have any apple juice in them or b) there's nothing to fear from apple juice or c) That you inform the phobic of either of these facts. It makes no difference to them to tell them to stop crying and cowering when they see a Volkswagen because it contains no apple juice. That technique would only work if the fear was a rational one. It isn't in this case. It doesn't make any difference if someone with a phobia of man-made chemicals even understands even one thing about such chemicals, or where they are, or anything else. The fear manifests itself randomly and without any rational cause. --Jayron32 16:38, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Howie Mandel's situation is a good example. He's got a phobia about germs, crowds, etc. He's a very smart guy; he's been very open about it, and very aware of it; but that doesn't fix it. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:44, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

Pigeon spikes on a TV aerial

[edit]Pigeons like to sit on my TV aerial and they poo all over my door step. If I attach plastic pigeon spikes to the aerial, will this have an affect on my TV reception? Alternatively is there another way to keep the pigeons away? Thanks! --TrogWoolley (talk) 09:10, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Plastic ones won't (although, given the voodoo that is antenna operation, you might find the pigeons actually improved reception). -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 09:29, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I can't believe we don't have an article about bird deterrents, but this website has information about TV aerial defence that you might find useful.--Shantavira|feed me 10:54, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- There's a Bird control spike article that the OP might find useful. Word to the wise about those spikes - they don't really stop birds from *trying* to fit their bodies around them and land there, and (speaking from a UK perspective, though this is likely true in a lot of other places too) if birds happen to get stuck on the spikes, you can find yourself in trouble with the law. --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 11:17, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks. I looked everywhere for that article. I will add some links to it.--Shantavira|feed me 11:38, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Or one of these that work surprisingly well if you have a suitable site close to the aerial. Richard Avery (talk) 13:14, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Those actually work on pigeons? Heh. Gulls and corvids will ignore them completely, from what I hear (presumably they see them as plastic owls). --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 00:20, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- One obvious solution is to move your antenna so it isn't directly above your door step. It seems to me that such a location brings other risks, like icicles falling on you in winter and the entire antenna falling on you in high winds. StuRat (talk) 15:05, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

Thanks for the advice - I've ordered spikes --TrogWoolley (talk) 17:51, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

DNA question (extended version)

[edit]I asked a question like this before but not like this, and the answers didn't really help :/ so I ask a new version, if you don't answer all of them, just give me a brief explanation that works...

What is the difference between the nuclei content of:

1.two different cells of one tissue in my body?(is there any?)

2.two cells of two different tissues in my body?(if they're identical, then why are the cells different?Is there a mechanism that doesn't let some genes work or something? explain)

3.a cell from my body and a cell from my brother's body?

4.a cell from my body and a cell from someone who is not closely related to me?

5.a cell from my body and a cell from a chimp's body?

and what is the difference between gene, DNA, genome and allele? I mean all they say is that in the nucleus is chromosomes which are made of DNA is it only made of DNA?is the DNA on the surface of the chromosome, or is it in its internal parts too?(I prefer visual answers...)... in order to fully understand the questions I asked above, do I need professional education?--Irrational number (talk) 10:44, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The DNA in each cell nucleus in your body is exactly the same (save novel point mutations etc.) it is the epigenetics that differs between cell types. Cell differentiation is an important part of developmental biology, this field looks at how identical embryonic stem cells can from a human body with cell types that seem entirely unrelated. Alas, I hated developmental biology (too many ventraldermowhatsits) so I cannot give you a comprehensive answer. In simple terms, though, during development identical cells begin to differentiate based on different concentrations of diffusible chemicals, which gives them an idea of their 'location' in the developing embryo, and they have transcription factors which will then act to change gene expression in some cells, forcing them to enter a specific lineage.

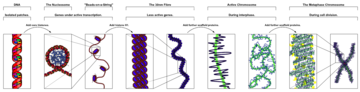

The various levels of DNA organisation, showing how DNA makes up a chromosome. - To your last questions: DNA is packaged into chromosomes (see image). You don't need a professional education, just reading DNA, chromosome, genome and epigenetics would answer most of your questions Jebus989✰ 10:57, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Irrational number, you may be getting confused between "nuclei" and DNA. The nucleus is full of all sorts of things other than just the DNA, including the molecular machinery necessary to transcribe DNA into mRNA and to replicate DNA during the cell cycle. In any case, different cells of your body most certainly have different numbers of nuclei and hence different DNA content. Mature erythrocytes (red blood cells) have no nucleus and contain all the mRNA and protein they need for the 100-120 days they will circulate. Liver cells can undergo fusion and thus have polyploid DNA content of 4N or 8N. Muscle cells can do the same. Your mature gametes (egg and sperm) have a haploid DNA content of 1N. Although the DNA content certainly does have something to do with the function of the cell, the explanation Jebus gave above essentially describes how different cells in the body can express such different characteristics (compare a pyramidal neuron to an epithelial cell). There is more on this topic in cellular differentiation. In questions 3-5 you seem to be asking about the level of DNA identity between different people or organisms, not about the nuclei. Read gene and human genetic variation and then ask more specific questions if there are still things you don't quite understand. --- Medical geneticist (talk) 12:57, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Actually liver cells don't fuse much that I know of, but they tend not to bother finishing with cell division after duplicating the nuclear DNA. As a rule such polyploidy is common throughout the animal kingdom in older, more specialized portions of tissues that are fulfilling some specialized function before eventually being eliminated by apoptosis, necrosis, shedding, or some other means. The cells that regenerate and replace organs tend to stay at the formal 2n chromosome number. Skeletal muscle is a very special case in that the cells fuse together into long tubes so that the individual actin and myosin fiber units can link up with maximum efficiency, but they retain separate nuclei.

- Other variations occur in B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes, where snippets of DNA are randomly cut out to produce a variety of antibodies or T cell receptors that (perhaps) recognize different antigens. But it is amazing how seldom the cellular DNA is actually modified, considering how many cells are specialized and deactivate pieces of DNA by DNA methylation, histone modification and other means. Apparently DNA splicing, even in the hands of nature, is not altogether safe or sure for the patient. The ability of animals to be cloned from almost any somatic cell is not something required by evolution or any law of nature, but an odd happenstance. Wnt (talk) 14:14, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

I don't think you are going to get the level of answer you are looking for from a Wikipedia Reference desk. You really need to get hold of a good introductory book on basic genetics and read it. Looie496 (talk) 14:45, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

can u introduce one, Looie?--Irrational number (talk) 14:52, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm not the best person to give a recommendation -- I've sort of absorbed this stuff out of the atmosphere over the course of 20 years. Both The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins and Genome by Matt Ridley are highly readable and contain the information you're looking for, but I can't assert that there isn't anything better out there. Looie496 (talk) 02:45, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

"Suitspace" question

[edit]how does your suitspace hel you travelon the planet — Preceding unsigned comment added by 122.108.36.167 (talk) 11:59, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I created a new header for this question as it does not appear to be related to the one above. --- Medical geneticist (talk) 12:31, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I believe your "spacesuit" provides you with your normal operating tolerances for breathing purposes as well as temperature tolerances, among other purposes. Ambient temperatures and available gasses for respiration may be hostile to normal human operating tolerances on other planets. Thus such needs as oxygen supply and temperature control are two important needs that may be provided by a spacesuit.

- Besides the Space suit article, check out the articles linked to here. Bus stop (talk) 12:58, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Maintaining proper pressure is also an important human need that is likely to be provided by the space suit. Bus stop (talk) 13:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The basic answer to the original question is, "It helps you travel on the planet by keeping you alive." It serves the same purpose as a diving suit in the depths of the ocean, or a radiation suit in a contaminated area such as a nuclear plant. In some sense, it hinders travel because it's big and bulky. But that's the tradeoff for staying alive. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 13:18, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- American space suits seem to operate a 4.3 psi. Googlemeister (talk) 13:19, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Which is still perfectly OK because that's 4.3 psi of pure oxygen. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 01:54, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- American space suits seem to operate a 4.3 psi. Googlemeister (talk) 13:19, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- It helps you contact aliens, who then take you to other planets. Mitch Ames (talk) 14:52, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

How much DNA to I need?

[edit]How much DNA to I need? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 129.215.5.255 (talk) 12:24, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- It depends on what purpose you need it for. If it's a matter of forensically identifying who a drop of blood or bit of skin came from, a state of the art laboratory would only need the DNA from a few dozen cells. Roger (talk) 12:37, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I believe each and every cell of your body needs its own set of your own personal DNA. Bus stop (talk) 12:48, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Note: fully-mature red blood cells do not Jebus989✰ 14:18, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Then the simple answer to the question would be, "All of it." ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 13:12, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I believe each and every cell of your body needs its own set of your own personal DNA. Bus stop (talk) 12:48, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Isn't a part of human DNA redundant? (i.e. useless)Quest09 (talk) 13:42, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- In a sense, half of your DNA is redundant (if you're a human female, or 22/46 of it if you're human male) because you have pairs of the same chromosome number (male X/Y excepted)--each of your two Chromosome 17, for example, contains a copy of every Chromosome 17 gene. That's redundant gene coding, but Monosomy is a serious problem. Also, lots of our DNA is "noncoding DNA", however, that article mentions numerous roles for these parts of the genome other than simple "coding for proteins". DMacks (talk) 14:11, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- A lot of junk DNA could be cut out - might even have positive effects to do so. Alas, as with all the junk that accumulates around the house, there is always some little thingummabob mixed in with it that you'll sorely miss if you throw it out. Wnt (talk) 14:50, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Any examples of 'junk' DNA which are beneficial when lost? 'Junk DNA' is a very outdated term, only a fraction of what was initially considered 'junk' still bears that title Jebus989✰ 15:41, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Well, BRCA1 apparently has a role keeping junk DNA inactive [4] ... unfortunately it doesn't always work. I understand that biology uses everything, and by now some genes rely on repeat elements for regulation, which in a sense interact with every other repeat out there, making them all of some importance. And I understand that repeats, more typically interspersed between exons and genes, provide evolution with important guidance where to cut and paste. Even so, my guess is that if you could magically splice out the right 50% of the genome and make a few necessary corrections, the rest would work a lot better. Wnt (talk) 02:53, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm sorry to say that guess is completely out-of-step with the current view of human genetics. The 0.1% of DNA deleted from 'gene deserts' in mice is a comparative figure, or the slightly larger percentage in yeast which was found to have no effect (of course, not a positive effect, else natural selection would have pruned the genome a long time ago). And you'll note that that nature summary does not contain the word 'junk', silencing genes and even repeat regions far from implies they are junk, just that they may have a function which is undesirable in a healthy/mature/specific cell Jebus989✰ 08:33, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- There are species like Takifugu rubripes where the junk has been pruned. But there is an impediment to doing this: yes, there are bits of useful sequence scattered all throughout the junk. That doesn't mean though that the individual pieces of spam in the genome have some a useful role for the person who carries them. Wnt (talk) 15:07, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- Genome reduction should not be oversimplified as 'pruning junk', there is absolutely no evidence implicating 'junk DNA' (which I can't stress enough, is not a term a modern geneticist would use at all frequently). For another example (another obvious one), Mycobacterium leprae has lost masses of coding DNA in its genome reduction, there's no evidence of removing proportionally more 'junk' than protein coding genes. In fact it has lost so many coding genes that M. leprae is rendered an obligate host parasite Jebus989✰ 18:35, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- There are species like Takifugu rubripes where the junk has been pruned. But there is an impediment to doing this: yes, there are bits of useful sequence scattered all throughout the junk. That doesn't mean though that the individual pieces of spam in the genome have some a useful role for the person who carries them. Wnt (talk) 15:07, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm sorry to say that guess is completely out-of-step with the current view of human genetics. The 0.1% of DNA deleted from 'gene deserts' in mice is a comparative figure, or the slightly larger percentage in yeast which was found to have no effect (of course, not a positive effect, else natural selection would have pruned the genome a long time ago). And you'll note that that nature summary does not contain the word 'junk', silencing genes and even repeat regions far from implies they are junk, just that they may have a function which is undesirable in a healthy/mature/specific cell Jebus989✰ 08:33, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Well, BRCA1 apparently has a role keeping junk DNA inactive [4] ... unfortunately it doesn't always work. I understand that biology uses everything, and by now some genes rely on repeat elements for regulation, which in a sense interact with every other repeat out there, making them all of some importance. And I understand that repeats, more typically interspersed between exons and genes, provide evolution with important guidance where to cut and paste. Even so, my guess is that if you could magically splice out the right 50% of the genome and make a few necessary corrections, the rest would work a lot better. Wnt (talk) 02:53, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Any examples of 'junk' DNA which are beneficial when lost? 'Junk DNA' is a very outdated term, only a fraction of what was initially considered 'junk' still bears that title Jebus989✰ 15:41, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- A lot of junk DNA could be cut out - might even have positive effects to do so. Alas, as with all the junk that accumulates around the house, there is always some little thingummabob mixed in with it that you'll sorely miss if you throw it out. Wnt (talk) 14:50, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- In a sense, half of your DNA is redundant (if you're a human female, or 22/46 of it if you're human male) because you have pairs of the same chromosome number (male X/Y excepted)--each of your two Chromosome 17, for example, contains a copy of every Chromosome 17 gene. That's redundant gene coding, but Monosomy is a serious problem. Also, lots of our DNA is "noncoding DNA", however, that article mentions numerous roles for these parts of the genome other than simple "coding for proteins". DMacks (talk) 14:11, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Isn't a part of human DNA redundant? (i.e. useless)Quest09 (talk) 13:42, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

As far as DNA is concerned, no one has the foggiest idea what would happen if snippets were removed. We barely know why so much mutation is non-random. Collect (talk) 18:20, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I think that's selling a great deal of geneticists short; gene knockouts in model organisms are routine, we have a good idea of what happens when many genes are removed or silenced Jebus989✰ 18:59, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

In the US, do they know who is a legacy student?

[edit]I suppose there is no official list (due to privacy issues), but can US students more or less guess who entered a specific institution through a legacy program? Quest09 (talk) 13:33, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- For reference, the OP is talking about legacy preferences, the practice of some U.S. universities of granting preference (through less-strict admissions criteria) to family members of alumni. For instance, there is rampant speculation that George W. Bush's 'legacy' status is what got him into Yale despite his lacklustre academic credentials (his father, George H.W. Bush, was a Yale grad). TenOfAllTrades(talk) 14:13, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Universities are institutions dedicated to science. Quest09 (talk) 15:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- They can be, but more important then the universities is the question. Googlemeister (talk) 15:19, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Universities are institutions dedicated to science. Quest09 (talk) 15:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I don't believe the legacy preference is common among the selective criteria for science programs, which tend to be more oriented towards merit. I strongly associate it with law, political science and similar degrees. 88.9.108.128 (talk) 15:36, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Undergraduates are usually admitted without specifying what program they're going into. You seem to be talking more about grad school, where I have never really heard of such a thing as legacy admissions. --Trovatore (talk) 22:04, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I don't believe the legacy preference is common among the selective criteria for science programs, which tend to be more oriented towards merit. I strongly associate it with law, political science and similar degrees. 88.9.108.128 (talk) 15:36, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- They're also dedicated to humanities, languages, mathematics, computing, and miscellaneous, as well. (And some to entertainment, I suppose.) --Mr.98 (talk) 21:58, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- You know that guy who never goes to class, but he's been there for five years and they haven't kicked him out yet? If his dad has a major building on campus named after him, its a good chance the kid is getting some special treatment. It should be noted that it doesn't mean anything for you, the good student. What you get out of school is information; if you go to class every day and work hard you win, regardless of what the layabouts with the rich dads get for free. You aren't there to be a layabout rich asshole, you're there for an education. --Jayron32 16:30, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Well, people don't go to college just for education, they also care about prestige. If potential employers don't know for sure if you are one of those layabouts with the rich dad or just the good learner, it's also your loss. Quest09 (talk) 19:51, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I've spent a lot of time around Ivy League universities. The sure-fire way to tell if someone is a legacy is to see what they do on "Big Game" today. If they have to go to a family tailgate party where three generations of people come from around the country, you can be damned sure they're a legacy. I know of no other obvious way to tell. Their teachers do not get that information or anything like that. In my experience legacies are usually indistinguishable academically from the normal variation one sees in students. --Mr.98 (talk) 21:58, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Do US Universities publish public lists of everyone graduating each year? It would be fairly simple, at least with unusual surnames, to refer to past lists and compare them to present-day students. As mentioned, if there's a building with your name, it might also be a clue. --Colapeninsula (talk) 09:52, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- "Morgan" isn't such an "unusual surname" but I just thought you'd like this little ditty. Bus stop (talk) 02:18, 18 September 2011 (UTC)

heat exchanger

[edit]hi can anyone tell me why a heat exchanger is needed in steam power plants? in the steam plant cycle, water is boiled to get steam in high pressure and high temperature, and this high pressure is relieved in the turbine. so y do we need heat exchanger? we can directly pass the hot water to the boiler again to heat it rite, why cool down water and then heat it agin? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 117.192.216.156 (talk) 13:54, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I think in simple terms it is to condense it. To turn steam back to a liquid at the same temperature would need as much energy to compress it as you took out of it. This is way outside my field so I would wait for other comments to be sure.-- Q Chris (talk) 14:41, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I think you are discussing a closed system. The steam rises and then goes down a tube and back into the water. There are many problems with that design. The steam won't want to go back down unless it is cooled. Since it doesn't want to go down, the steam trying to rise has nowhere to go. All you get is a massive pressure buildup until something fails. By cooling the steam at the top, you can force it back down into the water supply, making room for more steam. -- kainaw™ 14:44, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

the cycle used in steam plants is like this (as mentioned in "Fundamentals of Thermodynamics", Sonntag, Borgnakke, Van Wylen, Wiley Publishers 2010): boiler heats water, steam is at high pressure (HP) and high temperature (HT). steam passes through turbine, steam is at HT and low pressure (LP). it then passes through condenser, it is now at low temperature (LT) and LP. the condensed water is again fed to the boiler. my question is that why we need condenser? anyway we boil same water again to make steam. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 117.192.205.91 (talk) 15:24, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- As explained above, if you don't cool down the steam before pumping it back into the the boiler, the act of pumping it in will require at least as much energy as you got from the turbine to begin with. Dauto (talk) 17:25, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Actually, there's a more fundamental reason for the condenser. This is because the power station is a heat engine, and like all other heat engines, derives its power not just from heat, but from the transfer of thermal energy from a heat source (gas or coal burning in the boiler) to a heat sink. (If you want to, you could compare it to a power dam, with the heat source in the place of the reservoir, the heat sink in place of the outflow, and the heat engine simply replacing the water-wheels that harvest the energy from the falling water. This is an over-simplification, but it can help conceptually.) It therefore needs both of those to function properly -- without a heat source, it obviously won't have any thermal energy to turn into electricity, and without a heat sink, the thermal energy would just back up with no place to go, therefore no heat transfer and no power generated. What the condenser does is act as the heat sink, allowing the heat to flow into the cold water, thus maintaining the flow of thermal energy. Note that it's possible to use the thermal energy of the hot water from the condenser in various ways, e.g. for home heating, etc. 67.169.177.176 (talk) 00:00, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

Neutrino chemistry

[edit]I find it appealing to think about the far future universe as one where small particles acting on very long time scales form interesting chemistry, so naturally I find this talk about "neutrino nuggets" interesting. Alas, if I only understood it! It postulates a force between neutrinos of varying mass mediated by accelerons:

- (parsing error corrected; units added)

- with a Feynman diagram of two neutrinos coming up from the bottom, linked horizontally by A, and moving away at top with acceleration ?? .

Now that's an inverse square law that, well, isn't - I'm not sure how the exponential in A works, what a variation in mass over a variation in A means, etc.

- Is there a way to get from this to a normal looking physical law expressing the attraction of neutrinos toward one another in terms some typical power law force?

- Can you use this to predict the size of a "neutrino atom", i.e. the distance and speed with which two neutrinos should circle each other to have an angular momentum of 1/2 Planck's constant?

Wnt (talk) 14:39, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I don't know anything about accelerons, but I'm pretty sure that equation is actually , where and are the neutrino and acceleron masses. This is presumably supposed to be the force arising from the Yukawa potential , but they left out a factor of from the derivative for some reason. Maybe they left it out because the cosmological constant is so tiny that is negligible at scales below billions of light years, but in that case they should have left out also. Regardless, you should be able to approximate this force as the inverse-square force where . This gives you a neutrino-ium Bohr radius of . But I don't know how to calculate g. -- BenRG (talk) 02:51, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks! I never thought about a simple parsing error. That said, I still don't actually understand the formula - what the heck kind of units is e to the (mass x distance) expressed in? I mean, the g constant can't even be in units of ekm or something, because e1*ekm = e1+km, not e1 km. That question applies to the Yukawa potential in general. In any case, whatever it means, I take it to mean that the neutrino attractive force is inverse square at shorter distances, but peters out at a range of "1/mA", whatever that is.

- Miscellaneous: I wonder if the force is always attractive, or if there's any combination of neutrino-like particles that repel one another? According to [5] it sounds like the neutrinos might form "nuggets" but then (under current conditions) oscillate to a flavor that can get away, like some kind of neutrino nugget radioactivity, but I probably have that all wrong... then there's the thought of how neutrinos are quantized and how the Pauli exclusion principle works. If you dump three identical neutrinos into these nuggets, I would guess that they can't circle each other all the same way at the Bohr radius, because from the perspective of at least one neutrino there must be two others at the same spin in the same orbit. But at higher orbits would they form p orbitals and such based on different orientations of angular momentum just like atoms? Wnt (talk) 20:42, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- You have to use natural units here (believe it or not but using SI units is much more complicated than using natural units). In natural units, Mass has the dimensions of inverse length, so m r is dimensionless. Now, if you don't express mass in inverse meters, but in kilograms, or in electron volts, you must convert it to an inverse length. You can do that using the formula for the Compton wavelength lambda = hbar/(mc) which is, of course, the same as 1/m if you put hbar = c = 1.

- You can think of SI units as using inconsistent units for quantitities, which then makes it necessary to put in conversion factors in formula. So, if you have a formula like L = L1 + L2 where the L's are lengths, but you insist on L1 always being given in kilometers and L2 in miles and you also insist on L1 having different dimensions than L2, because a lengths in Britain are fundamentaly incompatible with lengths in mainland Europe (you can't be in two places at the same time), then you would write: L = L1 + c L2, with c = 1.609344 kilometers/mile. Count Iblis (talk) 21:12, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- It might be a good idea to add something about units to Yukawa potential. Dragons flight (talk) 22:02, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- The problem I have with "natural units" is there are so many of them. If they're so natural there should only be one way to do it and no second thought about it. I like to have a check on an equation. Anyway, here it appears that the particle physics designation that h/2pi = c = 1 is being made, and therefore (reduced Planck constant) / (speed of light) = 1 = 1.054571726(47)×10−34 J s / (299792458 m/s) = 3.51767264 ×10−43 kg m. Thus 1 kg = 2.84278869 × 1042 m-1 and vice versa. Anyway, according to the talk the acceleron mass is less (perhaps much less) than about 10-4 eV = 1.78×10−40 kg, which divided by "one" = 500 m-1. Thus the neutrino force would have a range of at least 0.2 mm, perhaps much further (the comparison made to quintessence I think implies potentially a factor of 1029 further, i.e. a billion parsecs). Wnt (talk) 21:54, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- In the context of relativity and particle physics, you always add factors of c, ħ, and G (though obviously only if your problem is relativistic, quantum, and gravitational, respectively). You should think of ħ as the real fundamental constant of quantum mechanics; h = 2πħ is almost never used any more. It can be useful to carry the constants around as a check, but in my experience it's too distracting to be worth it. Also, it's often unclear where the constants ought to be. Mass and distance have traditional units, and exponents have to be unitless, so you're forced to write e−mrc/ħ; but should you write ħcg², with g remaining unitless, or should you absorb the units into g²? The Newtonian tradition is to put the units in the force constant, but particle physics has a tradition of unitless coupling constants.

- I assume that you would get some kind of shell structure in these neutrino nuggets, yes, and the atomic orbitals are probably a good first approximation.

- It's a theorem of quantum field theory that forces mediated by even-spin bosons are always attractive. The spin-2 case is gravity. In fact, I've never really thought about this before, but there ought to be a Higgs-mediated attractive force in the Standard Model that would look a lot like gravity, since the Higgs couples to particles in proportion to their masses. Odd, that. -- BenRG (talk) 08:44, 17 September 2011 (UTC)

about "flow separation" and "boundary layer separation"

[edit]Are the flow separation and boundary layer separation the same things?--Wolfch (talk) 16:19, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I'm not sure, but it seems from a few minutes of review that boundary layer separation is a more pronounced kind of flow separation that is necessarily associated with turbulent flow, while laminar flow can involve simple flow separation but not boundary layer separation. 69.171.160.167 (talk) 21:00, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Both effects are caused by the same physics (Adverse pressure gradients), so the difference is mainly one of semantics and terminology. "Boundary Layer Separation" typically refers to the transition from a laminar boundary layer to a turbulent one (like this), which is a nearly unavoidable effect based on the local Reynolds Number. On the other hand, "Flow Separation" typically refers to turbulent conditions caused by low pressure areas in the wake of an object, like a wing at high angles of attack. Mildly MadTC 14:51, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

Cabin Pressure vs. Outside

[edit]This BBC article about a man attempting to open the door of a plane at 36,000ft has got me intrigued, as the staff of the travel company said that it would have been impossible for the passenger to open the door, due to the pressure inside the cabin. This does not make sense to me. As I understand it, the pressure inside the cabin is greater than outside. Would this not have made it easier, rather than impossible, to open the door? KägeTorä - (影虎) (TALK) 17:07, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- No, because airplane doors open inward, with a lip holding them in. If not, airplane doors would blow off all the time. StuRat (talk) 17:08, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Ah, yes, of course. Silly me. --KägeTorä - (影虎) (TALK) 17:11, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Clarification: Those are emergency exit doors which open inward. Many main doors are "plug-type" in design, meaning the doors are bigger than the opening. These may still open outward, but must be pulled inward, rotated, then pushed out. StuRat (talk) 17:14, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Things were not always like that. D._B._Cooper managed to open the airplane door at the old good days, in the 70s, at the end of the era of uninspected airline travel. Quest09 (talk) 19:46, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Cooper jumped from an airstair, not a plug door. Regular (non-plug) hatches like those on airstair exits and cargo doors rely on a mechanical locking mechanism (a system of deadbolts) to keep the door secure and airtight. Cooper evidently knew a way to get the mechanism to unlock (even though the aircraft was at 10,000 feet (ref)); the flight crew felt the pressure drop as he did so, and once it was equalised he jumped. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 20:16, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The pressurization was off, so a plug door could also have been opened anyway. Cooper most probably deliberately chose a 727 because it has an airstair in the tail, which is arguably the only "safe" usable mid-air exit on any common jet airliner that existed in the US at the time. Roger (talk) 20:31, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Cooper jumped from an airstair, not a plug door. Regular (non-plug) hatches like those on airstair exits and cargo doors rely on a mechanical locking mechanism (a system of deadbolts) to keep the door secure and airtight. Cooper evidently knew a way to get the mechanism to unlock (even though the aircraft was at 10,000 feet (ref)); the flight crew felt the pressure drop as he did so, and once it was equalised he jumped. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 20:16, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The airstair doors were re-designed after this incident: see here Cooper_vane. Apparently, Cooper didn't need any special knowledge at his time to open this door. Quest09 (talk) 20:38, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- United Airlines Flight 811#Cause discusses the locking mechanism on a cargo door, and describes how an electrical fault caused this door to unlock at altitude and blow out. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 20:21, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

Philippine_Airlines_Flight_812 might be of interest here: it's the case of a hijacker who managed to open the door of an Airbus at the altitude of 1,800 meters. Quest09 (talk) 20:38, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Airlines only usually pressurize to around 2500 meters equivalent altitude anyway, so the doors would open at low altitude. Googlemeister (talk) 20:44, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Additionally, there is something else blocking the (plug) door: the air flowing around the plane won't let you open a door of a Boeing, for example, that it hinged like a car door. Quest09 (talk) 20:52, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- The source article says that the Philippines hijacker used a gun to persuade the pilots to go down to 6000 feet and depressurize the airplane before opening the door. The pilots also helpfully added a rip cord to his homemade parachute. The article also says that when he got frightened and clung to the door for dear life, a flight attendant gave him a helpful push to get him started. :) Unfortunately I don't see the source for that - I kind of wonder about that, what happened to the flight attendant. In the U.S. any employee who does anything heroic, whatever the description, gets fired and blackballed from the industry (see also Challenger disaster) but I don't know if that's how it is in the Philippines. Wnt (talk) 19:13, 23 January 2013 (UTC)

- Additionally, there is something else blocking the (plug) door: the air flowing around the plane won't let you open a door of a Boeing, for example, that it hinged like a car door. Quest09 (talk) 20:52, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

the matter of dark energy

[edit]as you know dark energy exsits surly.....a fact now understood by many but as to the expansion of the universe and dark energy as I understand what you think the universe will shrink ? I think not the dark energy will not allow this to happen that is the foremost and purpose of this matter wether it is in the physical of the now or in the physical of another dimension or the future minds no hinderence for the future is now,,,, as also is of the so called past... time is only an equation of the human mind as is this dimension taken that into perpective the human mind is not fully formed and for sure not working to its fullest..... we as race are only just born....I would love to speak to you ,,,you have proved many of my knowings often laughed at by those of so called intelligence to be not only wrong but miss conconcived please do not get me wrong but most scientist close there minds to the impossible but was not the atom an impossible thing 200 years ago as to was quark my knowings are by truma a strong way to learn my body has passed so called death more then once this i can prove medically also not a willing idea of my own but I side track as to the shrinkage of the universe you are wrong this will not happen the universe isa expanding into enthropie maybe may spelling is wrong but you did say space did not excist but your wrong a doiffernt type of space did excist AND THAT IS WHAT THE UNIVERSE IS EXPANDUING INTO before the universe was born only centinent intelligences of pure dark energy was alive of course not in pyhsical human way but alive for many a million years in our time problem was when they met all was ok problem was that when they took all that was they with them leaveing 0 for thew host ahhhhhhh time to create a mote in gods so called eye and the universe was born nbow i can keep what you know and you can keep what i know but a problem was also born lack of memory born to with the creation of physical life itself sorry if you would like to email me please do ny mind is afire — Preceding unsigned comment added by 180.180.190.24 (talk) 19:40, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- We have an article on the ultimate fate of the universe, which includes a section noting that current scientific consensus favors an expanding open universe driven in large part by dark energy. Beyond that, Wikipedia is not an appropriate venue for you to develop or publicize your personal philosophy. — Lomn 19:50, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

google "The Last Question" by Isaac Asimov and read it. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.45.168.74 (talk) 20:27, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, do read the articles, and allow your mind to cool a little from its fire. Dark energy, if it exists, is part of the physical universe, not some god-like intelligence. Dbfirs 20:34, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I also suggest you learn about spell checkers. That is, only if you want us to read your questions, of course. --Lgriot (talk) 09:41, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, do read the articles, and allow your mind to cool a little from its fire. Dark energy, if it exists, is part of the physical universe, not some god-like intelligence. Dbfirs 20:34, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- A little Learning is a dang'rous Thing;

- Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring:

- There shallow Draughts intoxicate the Brain,

- And drinking largely sobers us again.

- Fir'd at first Sight with what the Muse imparts,

- In fearless Youth we tempt the Heights of Arts,

- While from the bounded Level of our Mind,

- Short Views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

- But more advanc'd, behold with strange Surprize

- New, distant Scenes of endless Science rise!

- So pleas'd at first, the towring Alps we try,

- Mount o'er the Vales, and seem to tread the Sky;

- Th' Eternal Snows appear already past,

- And the first Clouds and Mountains seem the last:

- But those attain'd, we tremble to survey

- The growing Labours of the lengthen'd Way,

- Th' increasing Prospect tires our wandering Eyes,

- Hills peep o'er Hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

- Pope. 86.164.76.231 (talk) 15:21, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

I have a jeweler's magnifying loupe with out any power marking.. How do I decipher the power?

[edit]I have a jeweler's magnifying loupe with out any power marking.. Is there any way to conveniently (or not, if necessary) decipher the power of this lens? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.45.168.74 (talk) 20:02, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Measure how many times it enlarges a ruler's markings? 69.171.160.167 (talk) 21:05, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

I'm sorry if I seem a little inept but any suggestions on how to accurately mark the increase in size? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.45.168.74 (talk) 21:06, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- If you can print an image of known size on an acetate transparency, you could use a flashlight to project the image through the loupe onto a screen, and measure the output size. If you know the distance from the loupe to the screen (ideally at the focal distance), then you should be able to figure the out magnification... can anyone show us the specific equation to use for this calculation? Is it in lens_(optics)? SemanticMantis (talk) 21:30, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Here's a quick, rough method (to which 69.171 alluded above):

- Find a ruler with the same subdivisions (e.g. 1/10ths of an inch) over at least 6 inches (it can be a decimal ruler, the actual units don't matter).

- Put the ruler on a flat surface which allows you to see its markings easily (such as a sheet of paper on a table top).

- Put the loupe in one eye and move your head until the magnified markings are clear.

- Keeping your other eye open, allow your vision to superimpose the magnified subdivisions seen through the loupe over the unmagnified subdivisions of the same value being seen by your naked eye (this may take a few minutes of practice).

- Now simply count how many unmagnified subdivisions fit in to one magnified subdivision; the answer is the linear magnification in the "12 times" or "12 X dd" format commonly used for binoculars, telescopes and loupes, etc. [The "dd" refers to the diameter of the 'front' lenses of binoculars, etc, given in millimetres, so "12 x 50" is typical]. The result is actually quite likely to be 10x, because that's a common standard for jewellers' loupes.

- As a former amateur astronomer, I have often used this method to find the approximate magnification of an eyepiece of unknown power (on a particular telescope of known focal length, and thence the focal length of the eyepiece), by looking at a distant brick wall. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.197.66.32 (talk) 22:43, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

If language is a universal component of human existence...

[edit]...why does it require years to learn? Using a vehicle is much easier for us humans, and we didn't drive vehicles along evolution. Quest09 (talk) 20:44, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- It doesn't really require years. For children, I would say it takes some months to learn a new language. 88.9.108.128 (talk) 20:55, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)Just so we know ahead of time, can you tell us how many times you are going to compare some aspect of human life to learning to drive a car?

- For the record, every human can learn, without any training, the language of their parents in about 2-3 years before they are fairly fluent. Place a toddler at the drivers seat of a car and ask them to "figure it out by yourself" and see how long it takes before he can do so. Your question is silly because it is asking about different types of learning in humans from vastly different stages of their development. If you are genuinely interested in language acquisition (instead of just asking inane variations on "why is BLANK harder than driving a car"), back away from the computer and go to your local library and look for books on linguistics by Noam Chomsky and pay special attention to his writings about Universal grammar and Generative grammar. --Jayron32 21:01, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- A million times more people in this world know how to speak a language fluently than know to slow down, rather than speed up, when it's raining. Nevard (talk) 22:15, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- No kidding. Also, this question seems suspiciously familiar. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 22:27, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Spoken language seems to arise spontaneously in human beings as part of their neurological development. Written language is a specific human invention, one that is relatively recent (in terms of evolution of the species), as far as we can tell, and has only been independently invented a handful of times. The analogy with your previous question is that spontaneous music seems rather innate in humans, but written music is not. --Mr.98 (talk) 01:42, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

- Walking is a (nearly) universal component, but it takes around a year to learn (and much longer to learn how to throw a javelin at a deer, which is also fairly universal). Human beings (and all advanced organisms) have a natural development process: predators learn to hunt, birds learn to fly, etc. This involves physical and neurological development. --Colapeninsula (talk) 10:00, 16 September 2011 (UTC)

If politeness is a universal component of human existence...

[edit]...why does it require years to learn? Using a vehicle is much easier for us humans, and we didn't drive vehicles along evolution. Quest09 (talk) 21:09, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Do you have something to say to me? Maybe we should step outside... --Jayron32 21:13, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Evolution includes behavior, and how parents instruct their children on playing nice has had a long, long history. One of the advantages to having a brain is that you don't have to wait for biochemical mutation to change the adaptability of the species, you just change your behavior. Politeness, however, is a complex task and there isn't a single ideal way to do it, as various cultures have mutated with different approaches given different contexts. American culture is substantially less polite than, say, traditional Japanese culture, but the lack of politeness allows for other benefits, mostly in clearer communication. Even within a single culture there are usually several levels of politeness (within family, with friends, in business, in religious activities, etc...), and a lot of people being "impolite" is just applying the wrong level of politeness within their own culture. Driving is simpler, because there's generally, within a culture, one "right" way to do it. SDY (talk) 21:33, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- I don't know if American culture is less polite than traditional Japanese, I'd say simply that it's less marked, people care about different things, and you are not forced to show respect for some old dude, when in reality you don't care about him.88.9.108.128 (talk) 21:50, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- We have an instinct for empathy and a desire for 'tribe' to grow stronger, and a desire to be accepted by that tribe, but we are not born instinctively knowing whatever arbitrary rules of etiquette are in fashion this century. Even those instincts I mentioned are not truly "universal"; some people are selfish assholes, and like being selfish assholes.

- As for the vehicle thing, tool use is absolutely something that gave us an evolutionary edge. Our ability to understand how machines work, without too much trouble, is definitely an ability we evolved. We have to learn how the specific tools work, but that kind of learning is easy for our species. (And, of course, we've had vehicles since the stone age, in the form of rafts and canoes.)

- Now that we've answered your questions, where the heck are you getting these "universal component of human existence" nonsense, and why are you asking so many questions about it? APL (talk) 21:44, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Through a Google search for "universal component of human existence" , I could find more of them. Pain, suffering are "universal components of human existence" according to Buddhism. And sport is too a "universal component of human existence" . 88.9.108.128 (talk) 21:54, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

- Politeness is a weapon of war. And as with all arts of war, it is difficult to learn because it is not enough to be good at it, but to be better than most other people. People who feel no possibility of real conflict are perfectly rude to one another (the traditional nagging wife). Those who are a moment away from blood feud show perfect civility. But politeness is not merely a means to avert conflict; it is a method to keep information hidden, so that no one knows when they'll be stabbed in the back. It becomes a shared set of standards that people can singled out for violating (just see WP:Civility in action...). See also [6] on "good manners". Wnt (talk) 23:03, 15 September 2011 (UTC)

Humans have a tendency to seesaw between one extreme to another. People who are politically correct, tend to be too politically correct that it becomes blatantly farcical. Those who dislike being politically correct on the other hand, interpret not being PC as to be the rudest you can be as possible (schadenfreude). Both are attempts to 'rebel' against imposed social norms. And politeness is really just that - a social norm. Though it's not instinctive, empathy is (wincing at the sight of another person getting hurt for example). In the best possible usage, politeness is simply a deference to empathy, The Golden Rule, do not do unto other what you do not want others to do unto you. The willingness to mitigate the amount of hurt, shame, or simply even inconvenience inflicted on another person by your choice of words or actions, sometimes at a personal cost, something reflected in different religions and cultures.

But yeah, the extent of empathy is often limited in some people. The farther people are from the culture of the speaker, the less likely he will be to experience empathy for them. A throwback to tribalism I guess in which while you must be able to empathize with fellow tribe members, you must also be wary of strangers for the tribe's survival. Nationalism and racism are like this, on a larger scale, people from different cultures still view each other as potential rivals for resources necessary for their "tribe's" growth. The level of politeness shown to another is also reflective of the the imbalance in power and threat capability. The more powerful one party is over another (whether real or imaginary), the less likely they will be to observe politeness in communications (arrogance). See Politeness theory.