United Kingdom invocation of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| UK membership of the European Union (1973–2020) |

|---|

|

On 29 March 2017, the United Kingdom (UK) invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) which began the member state's withdrawal, commonly known as Brexit, from the European Union (EU). In compliance with the TEU, the UK gave formal notice to the European Council of its intention to withdraw from the EU to allow withdrawal negotiations to begin.

The process of leaving the EU was initiated by a referendum held in June 2016 which resulted in 52% voting in favour of British withdrawal. In October 2016, the British prime minister, Theresa May, announced that Article 50 would be invoked by "the first quarter of 2017".[1] On 24 January 2017 the Supreme Court ruled in Miller I that the process could not be initiated without an authorising Act of Parliament, and unanimously ruled against the Scottish Government's claim in respect of devolution. Consequently, the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 empowering the prime minister to invoke Article 50 was enacted in March 2017.

Invocation of Article 50 occurred on 29 March 2017, when Tim Barrow, the Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom to the European Union, formally delivered by hand a letter signed by the prime minister to Donald Tusk, the president of the European Council in Brussels.[2] The letter also contained the United Kingdom's intention to withdraw from the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom). This means that the UK was scheduled to cease being a member of the EU at the end of 29 March 2019 Brussels time (UTC+1), which would be 23:00 on 29 March British time.[3][4] This was extended by two weeks to give the Parliament of the United Kingdom time to reconsider its rejection of the agreement on withdrawal conditions, particularly in the House of Commons. The UK was due to leave the EU at the end of 12 April 2019 (24:00 Central European summer time; 23:00 British summer time), however a further "flexible" extension was granted until 31 October 2019 after talks at the European Council meeting on 10 April.[5] After another extension in October 2019 and subsequent negotiations, a withdrawal agreement was negotiated in late October 2019 and ratified by both parties in January 2020: consequently the UK left the EU at 23:00 on 31 January 2020 and entered the transition period.

Background

[edit]The first ever invocation of Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union was by the United Kingdom, after the Leave vote in the 2016 referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union.

When David Cameron resigned in June 2016, he stated that the next prime minister should activate Article 50 and begin negotiations with the EU.[6]

At the time of the invocation of Article 50 the United Kingdom had been a full member state of the European Communities / European Union since its accession on 1 January 1973, some forty-four years earlier.

Views on invocation

[edit]Necessity of invoking Article 50

[edit]The British government stated that they would expect a leave vote to be followed by withdrawal, not by a second vote.[7] In a leaflet sent out before the referendum, the British government stated "This is your decision. The Government will implement what you decide."[8] Although Cameron stated during the campaign that he would invoke Article 50 straight away in the event of a leave victory,[9] he refused to allow the Civil Service to make any contingency plans, something the Foreign Affairs Select Committee later described as "an act of gross negligence".[10]

Unlike the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011, which contained provisions for an "alternative vote" system which would have become operative only if approved by the voting result in the referendum held under the Act,[11] the European Union Referendum Act 2015 did not state that the government could lawfully invoke Article 50 without a further authorising Act of Parliament.

Following the referendum result, Cameron announced before the Conservative Party conference that he would resign by October, and that it would be for the incoming prime minister to invoke Article 50.[12] He said that "A negotiation with the European Union will need to begin under a new Prime Minister, and I think it is right that this new Prime Minister takes the decision about when to trigger Article 50 and start the formal and legal process of leaving the EU."[13]

After a court case, the government introduced a bill that was passed as the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017.

Article 50 process

[edit]Article 50 provides an invocation procedure whereby a member can notify the European Council and there is a negotiation period of up to two years, after which the treaties cease to apply with respect to that member—although a leaving agreement may be agreed by qualified majority voting.[14] In this case, 20[a] remaining EU countries with a combined population of 65% must agree to the deal.[16] Unless the Council of the European Union unanimously agrees to extensions, the timing for the UK leaving under the article is the mandatory period ending at the second anniversary of the country giving official notice to the EU. The assumption is that new agreements will be negotiated during the mandatory two-year period, but there is no legal requirement that agreements have to be made.[17] Some aspects, such as new trade agreements, may be difficult to negotiate until after the UK has formally left the EU.[18]

Renegotiation of membership terms

[edit]Negotiations after invoking Article 50 cannot be used to renegotiate the conditions of future membership as Article 50 does not provide the legal basis of withdrawing a decision to leave.[11]

On the other hand, the constitutional lawyer and retired German Federal Constitutional Court judge, Udo Di Fabio, has stated[19] that

- The Lisbon Treaty does not forbid an exiting country to withdraw its application for leaving, because the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties prescribes an initial notification procedure, a kind of period of notice. Before a contract under international law [such as the Lisbon Treaty], which had been agreed without specifying details of giving notice, can be effectively cancelled, it is required that the intention to do so is expressed 12 months in advance: in this matter there exists the principle of preserving existing agreements and international organisations. In this light, the declaration of the intention to leave would itself be, under EU law, not a notice of cancellation.

- Separate negotiations of the EU institutions with pro-EU regions [London, Scotland or Northern Ireland] would constitute a violation of the Lisbon Treaty, according to which the integrity of a member country is explicitly put under protection.

A February 2016 briefing note for the European Parliament stated that a withdrawal from the EU ends, from then on, the application of the EU Treaties in the withdrawing state, although any national acts previously adopted for implementing or transposing EU law would remain valid until amended or repealed, and a withdrawal agreement would need to deal with phasing-out EU financial programmes. The note mentions that a member withdrawing from the EU would need to enact its own new legislation in any field of exclusive EU competence, and that complete isolation of a withdrawing state would be impossible if there is to be a future relationship between the former member and the EU, but that a withdrawal agreement could have transitional provisions for rights deriving from EU citizenship and other rights deriving from EU law that the withdrawal would otherwise extinguish.[20] The Common Fisheries Policy is one of the exclusive competences reserved for the European Union; others concern customs union, competition rules, monetary policy and concluding international agreements.[21]

In oral evidence to a Select Committee of the House of Lords in March 2016, one of the legal experts (David Edward) stated that the German text of Article 50 could be taken to mean that the structure of future relations between the UK and EU will already have been established at the point when withdrawal takes place, which could be taken as a difference from the English text "the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with the withdrawing state setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal and taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union".[22]

Arguments for moving slowly

[edit]Nicolas J. Firzli of the World Pensions Council (WPC) argued in July 2016 that it could be in Britain's national interest to proceed slowly in the following months; Her Majesty's Government might want to push Brussels to accept the principles of a free trade deal before invoking Article 50, hopefully gaining support from some other member states whose economy is strongly tied to the UK, thus "allowing a more nimble union to focus on the free trade of goods and services without undue bureaucratic burdens, modern antitrust law and stronger external borders, leaving the rest to member states".[23]

May confirmed that discussions with the EU would not start in 2016: "I want to work with ... the European council in a constructive spirit to make this a sensible and orderly departure", she said. "All of us will need time to prepare for these negotiations and the United Kingdom will not invoke article 50 until our objectives are clear." In a joint press conference with May on 20 July, Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel supported the UK's position in this respect: "We all have an interest in this matter being carefully prepared, positions being clearly defined and delineated. I think it is absolutely necessary to have a certain time to prepare for that."[24]

Scottish Parliament

[edit]In February 2017, the Scottish Parliament voted with overwhelming majority against invoking Article 50.[25] After the British Government had nevertheless chosen to invoke Article 50, the Scottish Government was formally authorised by the Parliament by a vote of 69 to 59 to seek to hold a second Scottish independence referendum.[26]

Pre-notification negotiations

[edit]Prior to the British Government's invocation of Article 50, the UK stayed a member of the EU, had to continue to fulfil all EU-related treaties including possible future agreements, and was legally treated as a member. The EU has no framework to exclude the UK—or any member—as long as Article 50 was not invoked, and the UK did not violate EU laws.[27][28] However, if the UK had breached EU law significantly, there were legal venues to discharge the UK from the EU via Article 7, the so-called "nuclear option" which allows the EU to cancel membership of a state that breaches fundamental EU principles, a test that is hard to pass.[29] Article 7 does not allow forced cancellation of membership, only denial of rights such as free trade, free movement and voting rights.

At a meeting of the Heads of Government of the other states in June 2016, leaders decided that they would not start any negotiation before the UK formally invoked Article 50. Consequently, the president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, ordered all members of the EU Commission not to engage in any kind of contact with the UK's parties regarding Brexit.[citation needed] Media statements of various kinds still occurred. For example, on 29 June 2016, Tusk told the UK that they would not be allowed access to the European Single Market unless they accept its four freedoms of goods, capital, services, and people.[30] Merkel said, "We'll ensure that negotiations don't take place according to the principle of cherry-picking ... It must and will make a noticeable difference whether a country wants to be a member of the family of the European Union or not".[31]

To strike and extend trade agreements between the UK and non-EU states, the Department for International Trade (DIT) was created by Theresa May, shortly after she took office on 13 July 2016.[32] As of February 2017, the DIT employs about 200 trade negotiators[33] and is overseen by Liam Fox, the Secretary of State for International Trade.

Subjects of negotiation

[edit]Since Article 50 has been invoked, the United Kingdom will negotiate with the European Union the status of the 1.2 million British citizens living in the EU, the status of the 3.2 million EU nationals living in the UK. Issues relating to immigration, free trade, the freedom of movement, the Irish border, intelligence-sharing and financial services will also be discussed.[34]

Process

[edit]Initial speculation

[edit]During the referendum David Cameron stated that, "If the British people vote to leave, [they] would rightly expect [the invoking of Article 50] to start straight away",[35] and there was speculation[by whom?] that he would do this on the morning with Eurosceptic MPs calling for caution to assess the negotiating position[36] and Jeremy Corbyn calling for immediate invocation.[37] During a 27 June 2016 meeting, the Cabinet decided to establish a unit of civil servants, headed by senior Conservative Oliver Letwin, who would proceed with "intensive work on the issues that will need to be worked through in order to present options and advice to a new Prime Minister and a new Cabinet".[38]

Conservative Party leadership election

[edit]Instead of invoking Article 50 Cameron resigned as prime minister, leaving the timing to a successor. There was speculation in the UK that it would be delayed,[39] and the European Commission in July 2016 believed that Article 50 notification would not be made before September 2017.[40]

Following the referendum result, Cameron announced that he would resign before the Conservative party conference in October and that it would be for the incoming prime minister to invoke Article 50:[12]

A negotiation with the European Union will need to begin under a new Prime Minister, and I think it is right that this new Prime Minister takes the decision about when to trigger Article 50 and start the formal and legal process of leaving the EU.[13]

Cameron made it clear that his successor as prime minister should activate Article 50 and begin negotiations with the EU.[6] Among the candidates for the Conservative Party leadership election there were disagreements about when this should be: May said that the UK needed a clear negotiating position before triggering Article 50, and that she would not do so in 2016, while Andrea Leadsom said that she would trigger it as soon as possible.[41]

EU views

[edit]According to EU Economic Affairs Commissioner Pierre Moscovici, Britain had to proceed promptly. In June 2016 he said: "There needs to be a notification by the country concerned of its intention to leave (the EU), hence the request (to British Prime Minister David Cameron) to act quickly."[42] In addition, the remaining EU leaders issued a joint statement on 26 June 2016 regretting but respecting Britain's decision and asking them to proceed quickly in accordance with Article 50. The statement also added: "We stand ready to launch negotiations swiftly with the United Kingdom regarding the terms and conditions of its withdrawal from the European Union. Until this process of negotiations is over, the United Kingdom remains a member of the European Union, with all the rights and obligations that derive from this. According to the Treaties which the United Kingdom has ratified, EU law continues to apply to the full to and in the United Kingdom until it is no longer a Member."[43]

An EU Parliament motion passed on 28 June 2016 called for the UK immediately to trigger Article 50 and start the exit process.[44] There is no mechanism allowing the EU to invoke the article.[45] As long as the British Government has not invoked Article 50, the UK stays a member of the EU; must continue to fulfil all EU-related treaties, including possible future agreements; and should legally be treated as a member. The EU has no framework to exclude the UK as long as Article 50 is not invoked, and the UK does not violate EU laws.[27][28] However, if the UK were to breach EU law significantly, there are legal provisions to allow the EU to cancel membership of a state that breaches fundamental EU principles, a test that is hard to pass.[29] These do not allow forced cancellation of membership, only denial of rights such as free trade, free movement and voting rights.

May made it clear that discussions with the EU would not start in 2016. "I want to work with ... the European Council in a constructive spirit to make this a sensible and orderly departure" she said "All of us will need time to prepare for these negotiations and the United Kingdom will not invoke article 50 until our objectives are clear". In a joint press conference with May on 20 July 2016, Merkel supported the UK's position in this respect: "We all have an interest in this matter being carefully prepared, positions being clearly defined and delineated. I think it is absolutely necessary to have a certain time to prepare for that."[24]

Miller case

[edit]The Supreme Court ruled in the Miller case that an explicit Act of Parliament is necessary to authorise the invocation of Article 50.

The Constitution of the United Kingdom is unwritten and it operates on convention and legal precedent: this question is without precedent and so the legal position was thought to be unclear. The Government argued that the use of prerogative powers to enact the referendum result was constitutionally proper and consistent with domestic law[46] whereas the opposing view was that prerogative powers could not be used to set aside rights previously established by Parliament.[47][48][49]

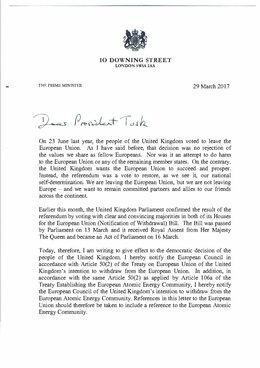

"I am writing to give effect to the democratic decision of the people of the United Kingdom. I hereby notify the European Council in accordance with Article 50 (2) of the Treaty on European Union of the United Kingdom's intention to withdraw from the European Union. In addition, in accordance with the same Article 50(2) as applied by Article 106a of the Treaty Establishing the European Atomic Energy Community, I hereby notify the European Council of the United Kingdom's intention to withdraw from the European Atomic Energy Community. References in this letter to the European Union should therefore be taken to include a reference to the European Atomic Energy Community."

Three distinct groups of citizens – one supported by crowd funding – brought a case before the High Court of England and Wales to challenge the government's interpretation of the law.[50]

On 13 October 2016, the High Court commenced hearing opening arguments. The Government argued that it would be constitutionally impermissible for the court to make a declaration that it [Her Majesty's Government] could not lawfully issue such a notification. The government stated that such a declaration [by the Court] would trespass on proceedings in Parliament, as the Court had ruled previously[51] when rejecting a challenge to the validity of the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty after the passing of the European Union (Amendment) Act 2008 but without a referendum.[52][53] Opening the case for the Plaintiffs, Lord Pannick QC told the Court that the case "raises an issue of fundamental constitutional importance concerning the limits of the power of the Executive". He argued Mrs May could not use royal prerogative powers to remove rights established by the European Communities Act 1972, which made EU law part of British law, as it was for Parliament to decide whether or not to maintain those statutory rights.[54]

On 3 November 2016, the High Court ruled[55] in R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union that only Parliament could make the decision on when or indeed whether to invoke Article 50.[56] The Government's appeal to the Supreme Court took place from 5 to 8 December 2016.[57] On 24 January 2017, the Supreme Court upheld the decision of the lower court by a majority of eight to three, declaring that the invocation of Article 50 could only come by an Act of Parliament.[58][59][60] The case was seen as having constitutional significance in deciding the scope of the royal prerogative in foreign affairs.[61] The Supreme Court also ruled that devolved legislatures in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have no legal right to veto the act.[62]

Other court cases

[edit]In February 2017, the High Court rejected a claim of several people against the Secretary of State centred on the UK's links with the European Economic Area.[63][64] However, a challenge to the notice of withdrawal continues in the courts of Scotland and in the European Court of Justice (below, "Reversibility").

British Parliament

[edit]On 2 October 2016, May announced that she intended to invoke Article 50 by the end of March 2017, meaning that the UK would be on a course to leave the EU by the end of March 2019.[65]

On 7 December 2016, the House of Commons approved a non-legally-binding motion supporting Article 50's invocation by 31 March 2017.[66]

As a direct consequence of the Supreme Court ruling the House of Commons voted by a majority of 384 votes (498 to 114) to approve the second reading of the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 to allow the prime minister to invoke Article 50 unconditionally.[67][68][69]

On 7 March 2017 the bill passed the House of Lords, though with two amendments.[70] Following further votes in the Commons and the Lords on 13 March 2017, these two amendments did not become part of the bill, so the bill passed its final reading unamended and it received royal assent on 16 March 2017.

Invocation of Article 50 has been challenged in the British courts on the basis that the British Parliament never voted to leave the EU despite the clear decision of the Supreme Court ruling. Campaigners argue the referendum result was not ratified by an act of Parliament, which they claim means the triggering of Article 50 is invalid.[71]

According to David Davis, when presenting the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017: "It is not a Bill about whether the UK should leave the European Union or, indeed, about how it should do so; it is simply about Parliament empowering the Government to implement a decision already made – a point of no return already passed", further saying that the Bill was "the beginning of a process to ensure that the decision made by the people last June is honoured".[72]

Formal notification

[edit]In October 2016, May announced that the government would trigger Article 50 by "the first quarter of 2017".[1] She announced on Monday 20 March 2017 that the UK would formally invoke Article 50 on Wednesday 29 March 2017, meeting her self-imposed deadline.[73] The letter invoking Article 50 was signed by May on 28 March 2017,[74] and was hand-delivered on 29 March by Tim Barrow, the Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom to the European Union, to the president of the European Council in Brussels.[75][2] The letter also contained the United Kingdom's intention to withdraw from the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom). In response on 31 March, Tusk sent draft negotiation guidelines to the leaders of the EU to prepare for the upcoming Brexit negotiations.[76]

Reversibility

[edit]Differing views have been expressed on whether the UK's invocation of Article 50 can be revoked.[77] In December 2018, the European Court of Justice ruled in the Wightman v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union case that a country that had given notice under Article 50 to leave the EU could exercise its sovereign right to revoke its notice.[78]

British government lawyers had argued that the Article 50 process could not be stopped.[79] An Irish court case challenging this view was later abandoned.[80] Lord Kerr has asserted that the Article 50 notification can be revoked unilaterally.[81]

British barrister Hugh Mercer QC noted before Article 50 was invoked that: "Though Art. 50 includes no express provision for revocation of the UK notice, it is clearly arguable for example on the grounds of the duties of sincere cooperation between member states (Art. 4(3) of the Treaty on European Union) that, were the UK to feel on mature reflection that leaving the EU and/or the European Economic Area (EEA) is not in the national interest, the notice under Art. 50 could be revoked."[82]

US law professor Jens Dammann argues: "there are strong policy reasons for allowing a Member State to rescind its declaration of withdrawal until the moment that the State's membership in the European Union actually ends" and "there are persuasive doctrinal arguments justifying the recognition of such a right as a matter of black letter law".[83]

EU politicians have said that if the UK changes its mind, they are sure a political formula will be found to reverse article 50, regardless of the technical specifics of the law.[84] According to the German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble, "The British Government has said we will stay with the Brexit. We take the decision as a matter of respect. But if they wanted to change their decision, of course, they would find open doors."[85]

On 29 March 2017, the EU Commission stated "It is up to the United Kingdom to trigger Article 50. But once triggered, it cannot be unilaterally reversed. Notification is a point of no return. Article 50 does not provide for the unilateral withdrawal of notification."[86] Similarly, the European Parliament Brexit committee headed by Guy Verhofstadt has stated that "a revocation of notification [by Article 50] needs to be subject to conditions set by all EU27, so that it cannot be used as a procedural device or abused in an attempt to improve on the current terms of the United Kingdom's membership".[87][88] The European Union Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs has stated that a hypothetical right of revocation can only be examined and confirmed or infirmed by the EU institution competent to this purpose, namely the CJEU.[89]

However, in July 2016 the German jurist Di Fabio argued, on the basis of international law, that a triggering of Article 50 can be revoked: "in EU law, the declaration of intention to leave is not itself a notification of withdrawal; rather, at any time and at least until the Treaty becomes inapplicable, it can be retracted or declared to have become redundant".[90]

In October 2017, barrister Jessica Simor QC of the leading London law firm Matrix Chambers lodged a freedom of information request to the prime minister or disclosure of legal advice which, she claims, states that the UK government can withdraw the Article 50 application at any time before 29 March 2019; she notes that Article 50 provides only for notification of an intention to withdraw and contends that such intention can be changed at any time before actual withdrawal.[91]

In February 2018, a crowd-funded petition by a cross-party group of Scottish politicians for judicial review of the notice was rejected by Scotland's Court of Session, but in March the Court overturned that decision.[92] On 20 November 2018, an attempt by the British government to prevent the European Court of Justice (ECJ) hearing the case failed and on 27 November 2018 the ECJ examined the legal arguments.[93]

On 4 December 2018, the responsible Advocate General to the ECJ published his preliminary opinion that a country could unilaterally cancel its withdrawal from the EU should it wish to do so, by simple notice, prior to actual departure.[94] While not being a formal ECJ judgement, it was seen as a good indication of the court's eventual decision.[95] On 10 December the ECJ decided that a notice of withdrawal can be revoked unilaterally, i.e. without approval by the other EU members, provided that the decision to revoke is made according to the country's constitutionally established procedures.[96] The case now returns to the Court of Session, to apply this ruling. The British Government immediately affirmed that it did not intend to propose revocation.[97]

Extension

[edit]Article 50 allows the maximum negotiation period of two years to be extended by a unanimous decision by the European Council and the state in question. For Brexit this has been done three times.

- The first time, on 22 March 2019, Brexit was postponed until 12 April if no deal was agreed by UK, and 22 May 2019 if the UK accepted the negotiated deal before 12 April.

- The second time, on 10 April 2019, Brexit was postponed until 31 October 2019, before which UK has to accept the negotiated deal, or before that as decided by the UK. The UK had to hold the 2019 European Parliament election (23 May) to be allowed to remain after 1 June, which it has. One of the conditions attached to the extension being granted was that it could not be used to reopen or renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement.[98]

- The third extension, occurred in late October 2019 after a revised Withdrawal Agreement was negotiated, postponed Brexit until 23:00 UTC on 31 January 2020. The UK finally left the EU in accordance with the time agreed in the third extension.

See also

[edit]- Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty

- 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

- Brexit

- R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union

Notes

[edit]- ^ 72% of remaining member states are required for the agreement to pass the Council of the European Union, rather than the usual 55%, as the proposal does not come from the Commission or the high representative.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Brexit: Theresa May to trigger Article 50 by end of March". BBC News. 2 October 2016. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ a b Castle, Stephen (29 March 2017). "U.K. Initiates 'Brexit' and Wades into a Thorny Thicket". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Bloom, Dan (29 March 2017). "Brexit Day recap: Article 50 officially triggered on historic day as Theresa May warns: 'No turning back'". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "House of Commons Briefing Paper 7960, summary". House of Commons. 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "Special European Council (Art.50), 10/04/2019 – Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ a b Cooper, Charlie (27 June 2016). "David Cameron rules out second EU referendum after Brexit". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Wright, Ben (26 February 2016). "Reality Check: How plausible is second EU referendum?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ HM Government. "Why the Government believes that voting to remain in the European Union is the best decision for the UK. The EU referendum, Thursday, 23 June 2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ Staunton, Denis (23 February 2016). "David Cameron: no second referendum if UK votes for Brexit". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Patrick Wintour (20 July 2016). "Cameron accused of 'gross negligence' over Brexit contingency plans". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ a b Renwick, Alan (19 January 2016). "What happens if we vote for Brexit?". The Constitution Unit Blog. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Brexit: David Cameron to quit after UK votes to leave EU". BBC News. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ a b "EU referendum outcome: PM statement, 24 June 2016". gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Article 50(3) of the Treaty on European Union.

- ^ "Qualified majority". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Article 50: Theresa May to trigger Brexit process next week". BBC News. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ "EU referendum: Would Brexit violate UK citizens' rights?". BBC News. 4 July 2016. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ editor, Patrick Wintour Diplomatic (22 July 2016). "UK officials seek draft agreements with EU before triggering article 50". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Fabio, Udo Di (7 July 2016). "Zukunft-der-europaeischen-union Kopf-hoch". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Eva-Maria Poptcheva, Article 50 TEU: Withdrawal of a Member State from the EU, Briefing Note for European Parliament.(Note: "The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the author and any opinions expressed therein do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.")[1] Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "EU Competences". European Commission. 13 December 2016. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "HL Select Committee on the European Union" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (July 2016). "Beyond Brexit: Britain, Europe and the Pension Wealth of Nations". Pensions Age: 44. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ a b Mason, Rowena (20 July 2016). "Angela Merkel backs Theresa May's plan not to trigger Brexit this year". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Scottish parliament rejects Brexit in non-binding vote Archived 4 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, DW, 7 February 2017

- ^ "Sturgeon signs independence vote request". BBC News. 30 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Al Jazeera (27 June 2016). "George Osborne: Only the UK can trigger Article 50". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b Henley, Jon (26 June 2016). "Will article 50 ever be triggered?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b Rankin, Jennifer (25 June 2016). "What is Article 50 and why is it so central to the Brexit debate?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Heffer, Greg (29 June 2016). "'It's not single market a la carte' Donald Tusk tells UK it's free movement or nothing". Daily Express. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Chambers, Madeline (28 June 2016). "Merkel tells Britain no 'cherry-picking' in Brexit talks". Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Theresa May signals Whitehall rejig with two new Cabinet posts". civilserviceworld.com. Civil Service World. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Staff writer (4 February 2017). "Where should Britain strike its first post-Brexit trade deals?". The Economist. Trading places. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Article 50: What will be negotiated?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ David Cameron, Prime Minister (22 February 2016). "European Council". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 606. United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 24–25. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

If the British people vote to leave, there is only one way to bring that about, namely to trigger article 50 of the treaties and begin the process of exit, and the British people would rightly expect that to start straight away.

- ^ "Boris Johnson: no need to immediately trigger Article 50". Financial Times. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "Corbyn: "Article 50 has to be invoked now"". LabourList. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Proctor, Kate (27 June 2016). "Cameron sets up Brexit unit". Yorkshire Post. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Nixon, Simon (11 July 2016). "Brexit: Breaking up amicably is hard to do". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

there is a growing consensus that […] the government should delay invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, starting the clock on a maximum two-year divorce negotiation, until early 2017 at the earliest. That is provoking alarm in many European capitals, where there is an equally clear consensus that Article 50 should be invoked as soon as possible.

- ^ Kreijger, Gilbert (5 July 2016). "Sources: European Commission doesn't expect Britain to apply to leave E.U. before September 2017". Handelsblatt. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ Shirbon, Estelle; Sandle, Paul (3 July 2016). "Top candidates to lead Britain differ on Brexit urgency". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ AFP PTI (26 June 2016). "Britain must 'quickly' announce exit from EU: Commissioner". Business Standard India. Business Standard Private Ltd. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

The nation must notify Brussels of its intention to avoid prolonged uncertainty, EU's economic affairs commissioner said

- ^ "Statement by the EU leaders and the Netherlands Presidency on the outcome of the UK referendum". European Council. European Union. 26 June 2016. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

We now expect the United Kingdom government to give effect to this decision of the British people as soon as possible, however painful that process may be.

- ^ "Brexit vote: Bitter exchanges in EU parliament debate". BBC News. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ Stone, Jon (28 June 2016). "Nigel Farage Mocked and Heckled by MEPs During Extraordinary Speech". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Phipps, Claire; Sparrow, Andrew (5 July 2016). "Letwin says government can invoke article 50 without a vote in parliament". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "Leaving the EU: Parliament's Role in the Process". House of Lords Library. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Barber, Nick; Hickman, Tom; King, Jeff (27 June 2016). "Pulling the Article 50 'Trigger': Parliament's indispensable role". ukconstitutionallaw.org. UK Constitutional Law Association. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Judicial review litigation over the correct constitutional process for triggering Article 50 TEU". Lexology. 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Mishcons, Edwin Coe and heavyweight QCs line up as key Brexit legal challenge begins". Legal Week. 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Skeleton argument of the Secretary of State" (PDF). GOV.UK. October 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ "Britain ratifies EU Treaty". The Daily Telegraph. 18 June 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "UK ratifies the EU Lisbon Treaty". BBC News. 17 July 2008. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (13 October 2016). "Government cannot trigger Brexit without MPs' backing, court told". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union (High Court of Justice, Queen's Bench Division, Divisional Court 3 November 2016), Text.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen; Elgot, Jessica (3 November 2016). "Brexit plans in disarray as high court rules parliament must have its say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Highlights of Thursday at Supreme Court". BBC News. 8 December 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Brexit: Supreme Court says Parliament must give Article 50 go-ahead". BBC News. 24 January 2017. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Ram, Vidya. "U.K. govt. must get Parliament nod for Brexit: Supreme Court". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen; Mason, Rowena; Asthana, Anushka (24 January 2017). "Supreme court rules parliament must have vote to trigger article 50". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Gower, Patrick (19 July 2016). "Brexit Article 50 Challenge to Quickly Move to Supreme Court". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: Ministers 'not legally compelled' to consult AMs". BBC News. 24 January 2017. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Barnett, Owen (30 December 2016). "Fresh Brexit challenge in high court over leaving single market and EEA". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon; Hughes, Laura (3 February 2017). "Brexit legal challenge: High Court throws out new case over single market vote for MPs". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "Brexit: PM to trigger Article 50 by end of March". BBC News. 2 October 2016. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ "MPs vote to back PM's timetable for Article 50". Sky News. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Brexit: MPs overwhelmingly back Article 50 bill". BBC News. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Brexit: MPs overwhelmingly back Article 50 bill". BBC. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "House of Commons – European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill — Second Reading – Division". House of Commons. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (7 March 2017). "House of Lords defeats government for second time on article 50 bill". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Farand, Chloe (22 December 2017). "Brexit: Government facing High Court challenge to cancel Article 50". Independent. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ House of Commons Hansard "European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill debate" Archived 22 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Article 50: Theresa May to trigger Brexit process next week". BBC News. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Article 50: May signs letter that will trigger Brexit". BBC News. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Tusk, Donald [@eucopresident] (29 March 2017). "The Article 50 letter. #Brexit" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Macdonald, Alastair (31 March 2017). "'Phased approach' – How to read EU Brexit guidelines". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Staff writer (29 March 2017). "Reality Check: Can the UK change its mind on Article 50?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "CURIA - Documents". curia.europa.eu.

- ^ Halpin, Padraic (24 April 2017). "Irish court to consider Brexit reversibility case on May 31". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Carolan, Mary (29 May 2017). "Legal challenge to Brexit struck out by High Court". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

The proceedings were aimed at establishing if Britain can halt Brexit after triggering Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. The plaintiffs wanted the High Court to refer issues in the case for determination by the Court of Justice of the EU. … They sought various declarations or interpretations of the Treaties of the EU, including a declaration that article 50, once triggered, can be unilaterally revoked by the UK government.

- ^ Merrick, Rob; Stone, Jon (21 February 2017). "Brexit is reversible, says author of Brexit treaty". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ Mercer, Hugh (22 March 2017). "Could UK's notice to exit from EU be revoked?". New Law Journal (7739). LexisNexis: 1. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ Dammann, Jens (Spring 2017). "Revoking Brexit: Can member states rescind their declaration of withdrawal from the European Union?". Columbia Journal of European Law. 23 (2). Columbia Law School: 265–304. SSRN 2947276. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2017. Preview. Archived 25 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Khan, Shehab (29 March 2017). "Brexit can be stopped after Article 50 is triggered, EU politicians say". The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Peck, Tom (13 June 2017). "Brexit: Britain can still stay in the EU if it wants to, German finance minister says". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "European Commission – Fact Sheet. Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union – Q&A" (Press release). 29 March 2017. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ "European Plenary sitting 10.4.2017". European Parliament. 10 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "European Parliament resolution of 5 April 2017 on negotiations with the United Kingdom following its notification that it intends to withdraw from the European Union, paragraph L". European Parliament. 5 April 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "The (ir-)revocability of the withdrawal notification under Article 50 TEU – Conclusions" (PDF). The European Union Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs. March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Di Fabio, Udo (7 July 2016). "Zukunft der Europäischen Union: Kopf hoch! [Future of the European Union: Chin up!]". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2017. Original: "die Erklärung über die Absicht eines Austritts im Unionsrecht noch selbst gar keine Kündigung wäre, sondern jederzeit bis längstens zur Unanwendbarkeit der Verträge widerrufen oder für gegenstandslos erklärt werden kann".

- ^ Simor, Jessica (8 October 2017). "Why it's not too late to step back from the Brexit brink". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Tom (20 March 2018). "Scottish campaigners secure judicial review on halting Brexit". Herald Scotland. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Glenn (20 November 2018). "UK government fails in Brexit case appeal bid". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Article 50: Law officer says UK can cancel Brexit Archived 2 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine BBC News

- ^ Staff writer (27 November 2018). "Scotland's Brexit legal bid explained as European court to hear Article 50 challenge". Herald Scotland. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Judgment in Case C-621/18 Press and Information Wightman and Others v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union (press release)}" (PDF). Court of Justice of the European Union. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Politics live". The Guardian. 10 December 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "Special meeting of the European Council (Art. 50) (10 April 2019) – Conclusions" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

External links

[edit]- House of Commons Briefings: Brexit: How does the Article 50 process work? (Jan 2017)

- House of Commons Briefings: Brexit: Article 50 TEU at the CJEU (Dec 2018)

- House of Commons Briefings: Extending Article 50: could Brexit be delayed? (Mar 2019)

- House of Commons Briefings: Parliament and the three extensions of Article 50 (Oct 2019)

- The Brexit Papers, Bar Council, December 2016 Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- The United Kingdom’s exit from and new partnership with the European Union, February 2017 ("White paper")

- Letter from the Prime Minister to President Tusk, 29 March 2017

- Legislating for the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union (The Great Repeal Bill White Paper), 30 March 2017