Geography of India

Satellite view of the subcontinent | |

| Continent | Asia |

|---|---|

| Region | South Asia and Southeast Asia (Indian subcontinent) |

| Coordinates | 21°N 78°E / 21°N 78°E |

| Area | Ranked 7th |

| • Total | 3,287,263 km2 (1,269,219 sq mi) |

| • Land | 91% |

| • Water | 9% |

| Coastline | 7,516.6 km (4,670.6 mi) |

| Borders | Total land borders:[1] 15,200 km (9,400 mi) Bangladesh: 4,096.70 km (2,545.57 mi) China (PRC): 3,488 km (2,167 mi) Pakistan: 3,323 km (2,065 mi) Nepal: 1,751 km (1,088 mi) Myanmar: 1,643 km (1,021 mi) Bhutan: 699 km (434 mi) |

| Highest point | Kangchenjunga 8,586 m (28,169 ft) |

| Lowest point | Kuttanad −2.2 m (−7.2 ft) |

| Longest river | Ganges (or Ganga) 2,525 km (1,569 mi) |

| Largest lake | Loktak Lake (freshwater) 287 to 500 km2 (111 to 193 sq mi) Chilika Lake (brackish water) 1,100 km2 (420 sq mi) |

| Exclusive economic zone | 2,305,143 km2 (890,021 sq mi) |

India is situated north of the equator between 8°4' north (the mainland) to 37°6' north latitude and 68°7' east to 97°25' east longitude.[2] It is the seventh-largest country in the world, with a total area of 3,287,263 square kilometres (1,269,219 sq mi).[3][4][5] India measures 3,214 km (1,997 mi) from north to south and 2,933 km (1,822 mi) from east to west. It has a land frontier of 15,200 km (9,445 mi) and a coastline of 7,516.6 km (4,671 mi).[1]

On the south, India projects into and is bounded by the Indian Ocean—in particular, by the Arabian Sea on the west, the Lakshadweep Sea to the southwest, the Bay of Bengal on the east, and the Indian Ocean proper to the south. The Palk Strait and Gulf of Mannar separate India from Sri Lanka to its immediate southeast, and the Maldives are some 125 kilometres (78 mi) to the south of India's Lakshadweep Islands across the Eight Degree Channel. India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands, some 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) southeast of the mainland, share maritime borders with Myanmar, Thailand and Indonesia. The southernmost tip of the Indian mainland (8°4′38″N, 77°31′56″E) is just south of Kanyakumari, while the southernmost point in India is Indira Point on Great Nicobar Island. The northernmost point which is under Indian administration is Indira Col, Siachen Glacier.[6] India's territorial waters extend into the sea to a distance of 12 nautical miles (13.8 mi; 22.2 km) from the coast baseline.[7] India has the 18th largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 2,305,143 km2 (890,021 sq mi).

The northern frontiers of India are defined largely by the Himalayan mountain range, where the country borders China, Bhutan, and Nepal. Its western border with Pakistan lies in the Karakoram and Western Himalayan ranges, Punjab Plains, the Thar Desert and the Rann of Kutch salt marshes. In the far northeast, the Chin Hills and Kachin Hills, deeply forested mountainous regions, separate India from Burma. On the east, its border with Bangladesh is largely defined by the Khasi Hills and Mizo Hills, and the watershed region of the Indo-Gangetic Plain.[clarification needed]

The Ganges is the longest river originating in India. The Ganges–Brahmaputra system occupies most of northern, central, and eastern India, while the Deccan Plateau occupies most of southern India. Kangchenjunga, in the Indian state of Sikkim, is the highest point in India at 8,586 m (28,169 ft) and the world's third highest peak. The climate across India ranges from equatorial in the far south, to alpine and tundra in the upper regions of the Himalayas. Geologically, India lies on the Indian Plate, the northern part of the Indo-Australian Plate.

Geological development

India is situated entirely on the Indian Plate, a major tectonic plate that was formed when it split off from the ancient continent Gondwanaland (ancient landmass, consisting of the southern part of the supercontinent of Pangea). The Indo-Australian plate is subdivided into the Indian and Australian plates. About 90 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous Period, the Indian Plate began moving north at about 15 cm/year (6 in/yr).[8] About 50 to 55 million years ago, in the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era, the plate collided with Asia after covering a distance of 2,000 to 3,000 km (1,243 to 1,864 mi), having moved faster than any other known plate. In 2007, German geologists determined that the Indian Plate was able to move so quickly because it is only half as thick as the other plates which formerly constituted Gondwanaland.[9] The collision with the Eurasian Plate along the modern border between India and Nepal formed the orogenic belt that created the Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas. As of 2009[update], the Indian Plate is moving northeast at 5 cm/yr (2 in/yr), while the Eurasian Plate is moving north at only 2 cm/yr (0.8 in/yr). India is thus referred to as the "fastest continent".[9] This is causing the Eurasian Plate to deform, and the Indian Plate to compress at a rate of 4 cm/yr (1.6 in/yr).

Political geography

India is divided into 28 States (further subdivided into districts) and 8 union territories including the National capital territory (i.e., Delhi). India's borders run a total length of 15,200 km (9,400 mi).[1][10]

Its borders with Pakistan and Bangladesh were delineated according to the Radcliffe Line, which was created in 1947 during Partition of India. Its western border with Pakistan extends up to 3,323 km (2,065 mi), dividing the Punjab region and running along the boundaries of the Thar Desert and the Rann of Kutch.[1] This border runs along the Indian states and union territories of Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat.[11] Both nations delineated a Line of Control (LoC) to serve as the informal boundary between the Indian and Pakistan-administered areas of the Kashmir region. India claims the whole of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which includes areas now administered by Pakistan and China, which according to India are illegally occupied areas.[1]

India's border with Bangladesh runs 4,096.70 km (2,545.57 mi).[1] West Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram are the states which share the border with Bangladesh.[12] Before 2015, there were 92 enclaves of Bangladesh on Indian soil and 106 enclaves of India were on Bangladeshi soil.[13] These enclaves were eventually exchanged in order to simplify the border.[14] After the exchange, India lost roughly 40 km2 (9,900 acres) to Bangladesh.[15]

The Line of Actual Control (LAC) is the effective border between India and the People's Republic of China. It traverses 4,057 km along the Indian states and union territories of Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.[16] The border with Burma (Myanmar) extends up to 1,643 km (1,021 mi) along the eastern borders of India's northeastern states viz. Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram.[17] Located amidst the Himalayan range, India's border with Bhutan runs 699 km (434 mi).[1] Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh are the states which share the border with Bhutan.[18] The border with Nepal runs 1,751 km (1,088 mi) along the foothills of the Himalayas in northern India.[1] Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal and Sikkim are the states which share the border with Nepal.[19] The Siliguri Corridor, narrowed sharply by the borders of Bhutan, Nepal and Bangladesh, connects peninsular India with the northeastern states.

Physiographic regions

Regions

India can be divided into six physiographic regions. They are:

- Northern Mountains: Himalayas

- Peninsular Plateau: contains mountain ranges (Aravalli, Vindhayachal and Satpura ranges), ghats (Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats) and plateaus (Malwa Plateau, Chhota Nagpur Plateau, Southern Garanulite terrain, Deccan Plateau and Kutch Kathiawar plateau).

- Indo-Gangetic Plain or The Northern Plains

- Thar Desert

- Coastal Plains: Eastern Ghat folds and Western Ghats folds

- Islands- The Andaman and Nicobar islands and the Lakshadweep islands.

The Himalayas

An arc of mountains consisting of the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and Patkai ranges define the northern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent.[20] These were formed by the ongoing tectonic plates collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. The mountains in these ranges include some of the world's tallest mountains which act as a barrier to cold polar winds. They also facilitate the monsoon winds which in turn influence the climate in India. Rivers originating in these mountains flow through the fertile Indo–Gangetic plains. These mountains form the boundary between two biogeographic realms: the temperate Palearctic realm that covers most of Eurasia, and the tropical and subtropical Indomalayan realm which includes South Asia, Southeast Asia and Indonesia.[citation needed]

The Himalayas in India extend from Ladakh in the north to the state of Arunachal Pradesh in the east. Several Himalayan peaks in India rise above 7,000 m (23,000 ft), including Kanchenjunga (8,598 m (28,209 ft)) on the Sikkim–Nepal border, and Nanda Devi (7,816 m (25,643 ft)) in the Garhwal Himalayas of Uttarakhand. The snow line ranges between 6,000 m (20,000 ft) in Sikkim to around 3,000 m (9,800 ft) in Ladakh. The Himalayas act as a barrier to the frigid katabatic winds flowing down from Central Asia. Thus, northern India is kept warm or only mildly cooled during winter; in summer, the same phenomenon makes India relatively hot.[citation needed]

- The Karakoram range runs through Ladakh. The range is about 500 km (310 mi) in length and the most heavily glaciated part of the world outside of the polar regions. The Siachen Glacier at 76 km (47 mi) ranks as the world's second longest glacier outside the polar regions.[21] The southern boundary of the Karakoram is formed by the Indus and Shyok rivers, which separate the range from the northwestern end of the Himalayas.

- The Patkai, or Purvanchal, are situated near India's eastern border with Burma. They were created by the same tectonic processes which led to the formation of the Himalayas. The physical features of the Patkai mountains are conical peaks, steep slopes and deep valleys. The Patkai ranges are not as rugged or tall as the Himalayas. There are three hill ranges that come under the Patkai: the Patkai–Bum, the Garo–Khasi–Jaintia and the Lushai hills. The Garo–Khasi range lies in Meghalaya. Mawsynram, a village near Cherrapunji lying on the windward side of these hills, has the distinction of being the wettest place in the world, receiving the highest annual rainfall.[22]

The Peninsular Plateau

This is a large region of the Indian subcontinent located between the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, and is loosely defined as the peninsular region between these ranges that is south of the Narmada River.Having once constituted a segment of the ancient continent of Gondwanaland, this land is the oldest and most stable in India.

- Mountain ranges (clockwise from top-left)

- Aravali Range is the oldest mountain range in India, running across Rajasthan from northeast to southwest direction, extending approximately 800 km (500 mi).[23] The northern end of the range continues as isolated hills and rocky ridges into Haryana, ending near Delhi. The highest peak in this range is Guru Shikhar at Mount Abu, rising to 1,722 m (5,650 ft), lying near the border with Gujarat.[24] The Aravali Range is the eroded stub of an ancient fold mountain system.[25] The range rose in a Precambrian event called the Aravali–Delhi orogen. The range joins two of the ancient segments that make up the Indian craton, the Marwar segment to the northwest of the range, and the Bundelkhand segment to the southeast.

- Vindhya range, lies north of Satpura range and east of Aravali range, runs across most of central India, extending 1,050 km (650 mi).[26] The average elevation of these hills is from 300 to 600 m (980 to 1,970 ft) and rarely goes above 700 metres (2,300 ft).[26] They are believed to have been formed by the wastes created by the weathering of the ancient Aravali mountains.[27] Geographically, it separates Northern India from Southern India. The western end of the range lies in eastern Gujarat, near its border with Madhya Pradesh, and runs east and north, almost meeting the Ganges at Mirzapur.

- Satpura Range, lies south of Vindhya range and east of Aravali range, begins in eastern Gujarat near the Arabian Sea coast and runs east across Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. It extends 900 km (560 mi) with many peaks rising above 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[26] It is triangular in shape, with its apex at Ratnapuri and the two sides being parallel to the Tapti and Narmada rivers.[28] It runs parallel to the Vindhya Range, which lies to the north, and these two east–west ranges divide the Indo–Gangetic plain from the Deccan Plateau located north of River Narmada.

- Plateaus (clockwise from top-left)

- Malwa Plateau is spread across Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. The average elevation of the Malwa plateau is 500 metres, and the landscape generally slopes towards the north. Most of the region is drained by the Chambal River and its tributaries; the western part is drained by the upper reaches of the Mahi River.

- Chhota Nagpur Plateau is situated in eastern India, covering much of Jharkhand and adjacent parts of Odisha, Bihar and Chhattisgarh. Its total area is approximately 65,000 km2 (25,000 sq mi) and is made up of three smaller plateaus—the Ranchi, Hazaribagh, and Kodarma plateaus. The Ranchi plateau is the largest, with an average elevation of 700 m (2,300 ft). Much of the plateau is forested, covered by the Chhota Nagpur dry deciduous forests. Vast reserves of metal ores and coal have been found in the Chota Nagpur plateau. Southern Garanulite terrain: Covers South India especially Tamil Nadu excluding western and eastern ghats.

- Deccan Plateau, also called Deccan Trapps, is a large triangular plateau, bounded by the Vindhyas to the north and flanked by the Eastern and Western Ghats. The Deccan covers a total area of 1.9 million km2 (730,000 sq mi). It is mostly flat, with elevations ranging from 300 to 600 m (980 to 1,970 ft). The average elevation of the plateau is 2,000 feet (610 m) above sea level. The surface slopes from 3,000 feet (910 m) in the west to 1,500 feet (460 m) in the east.[29] It slopes gently from west to east and gives rise to several peninsular rivers such as the Godavari, the Krishna, the Kaveri and the Mahanadi which drain into the Bay of Bengal. This region is mostly semi-arid as it lies on the leeward side of both Ghats. Much of the Deccan is covered by thorn scrub forest scattered with small regions of deciduous broadleaf forest. Climate in the Deccan ranges from hot summers to mild winters.

- Kutch Kathiawar plateau is located in Gujarat state. The Kathiawar peninsula in western Gujarat is bounded by the Gulf of Kutch and the Gulf of Khambat. The natural vegetation in most of the peninsula is xeric scrub, part of the Northwestern thorn scrub forests ecoregion.

Ghats

The word ghati (Hindi: घाटी) means valley.[30] In Marathi, Hindi, Gujarati and Kannada, ghat is a term used to identify a difficult passage over a mountain.[31] One such passage is the Bhor Ghat that connects the towns Khopoli and Khandala, on NH 4 about 80 kilometres (50 mi) north of Mumbai. Charmadi Ghat of Karnataka is also notable. In many cases, the term is used to refer to a mountain range itself, as in the Western Ghats and Eastern Ghats. 'Ghattam' in Malayalam also refers to mountain ranges when used with the name of the ranges being addressed (e.g., paschima ghattam for Western Ghats), while the passage road would be called a 'churam'. Eastern Ghats on the east coast of India and Western Ghats on the west coast of India are the largest ghats in pensular India.[32]

- Western Ghats also known as Sahyadri (Benevolent Mountains) run along the western edge of India's Deccan Plateau and separate it from a narrow coastal plain along the Arabian Sea. The range covers an area of 140,000 km2 in a stretch of 1,600 km (990 mi) parallel to the western coast of the Indian peninsula,[28] from south of the Tapti River near the Gujarat–Maharashtra border and across Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujarat. to the southern tip of the Deccan peninsula.[33] The average elevation is around 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[28] Anai Mudi in the Anaimalai Hills 2,695 m (8,842 ft) in Kerala is the highest peak in the Western Ghats.[34] It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is one of the eight "hottest hot-spots" of biological diversity in the world.[35][36] It is sometimes called the Great Escarpment of India.[37] It is a biodiversity hotspot that contains a large proportion of the country's flora and fauna; many of which are only found here and nowhere else in the world.[38] According to UNESCO, Western Ghats are older than Himalayan mountains. It also influences Indian monsoon weather patterns by intercepting the rain-laden monsoon winds that sweep in from the south-west during late summer.[33] A total of thirty-nine properties including national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserve forests were designated as world heritage sites - twenty in Kerala, ten in Karnataka, five in Tamil Nadu and four in Maharashtra.[39][40] Ghati people, literally means the people of hills or ghats (valleys), is an exonym used for the marathi people specially those from the villages in Western Ghats, often in pejorative terms.[41][42][43]

- Eastern Ghats are a discontinuous range of mountains along India's eastern coast, which have been eroded and quadrisected by the four major rivers of southern India, the Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri.[44] These mountains extend from West Bengal to Odisha through Andhra Pradesh to Tamil Nadu in the south passing some parts of Karnataka and in the Wayanad region of Kerala. Parts of the coastal plains, including the Coromandel Coast region, lie between the Eastern Ghats and the Bay of Bengal.Though not as tall as the Western Ghats, some of its peaks are over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) in height.[28] The Nilgiri hills in Tamil Nadu lies at the junction of the Eastern and Western Ghats. Arma Konda (1,690 m (5,540 ft)) in Andhra Pradesh is the tallest peak in Eastern Ghats.[45] The Eastern Ghats are older than the Western Ghats, and have a complex geologic history related to the assembly and breakup of the ancient supercontinent of Rodinia and the assembly of the Gondwana supercontinent. The Eastern Ghats are made up of charnockites, granite gneiss, khondalites, metamorphic gneisses and quartzite rock formations. The structure of the Eastern Ghats includes thrusts and strike-slip faults[46] all along its range. Limestone, bauxite and iron ore are found in the Eastern Ghats hill ranges.

Indo-Gangetic plain

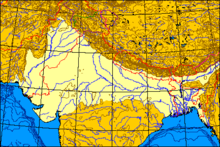

The Indo-Gangetic[47] plains, also known as the Great Plains are large alluvial plains dominated by three main rivers, the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra. They run parallel to the Himalayas, from Jammu and Kashmir in the west to Assam in the east, drain most of northern and eastern India and extend into Pakistan. The plains encompass an area of 700,000 km2 (270,000 sq mi). The major rivers in this region are the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra along with their main tributaries—Yamuna, Chambal, Gomti, Ghaghara, Kosi, Sutlej, Ravi, Beas, Chenab, and Tista—as well as the rivers of the Ganges Delta, such as the Meghna.

The great plains are sometimes classified into four divisions:

- The Bhabar belt is adjacent to the foothills of the Himalayas and consists of boulders and pebbles which have been carried down by streams. As the porosity of this belt is very high, the streams flow underground. The Bhabar is generally narrow with its width varying between 6 and 15 km (3.7 and 9.3 mi).

- The Tarai belt lies south of the adjacent Bhabar region and is composed of newer alluvium. The underground streams reappear in this region. The region is excessively moist and thickly forested. It also receives heavy rainfall throughout the year and is populated with a variety of wildlife.

- The Bangar belt consists of older alluvium and forms the alluvial terrace of the flood plains. In the Gangetic plains, it has a low upland covered by laterite deposits.

- The Khadar belt lies in lowland areas after the Bangar belt. It is made up of fresh newer alluvium which is deposited by the rivers flowing down the plain.

The Indo-Gangetic belt is the world's most extensive expanse of uninterrupted alluvium formed by the deposition of silt by the numerous rivers. The plains are flat making it conducive for irrigation through canals. The area is also rich in ground water sources. The plains are one of the world's most intensely farmed areas. The main crops grown are rice and wheat, which are grown in rotation. Other important crops grown in the region include maize, sugarcane and cotton. The Indo-Gangetic plains rank among the world's most densely populated areas.

Thar Desert

The Thar Desert (also known as the deserts) is by some calculations the world's seventh largest desert, by some others the tenth.[48] It forms a significant portion of western India and covers an area of 200,000 to 238,700 km2 (77,200 to 92,200 sq mi).[49] The desert continues into Pakistan as the Cholistan Desert. Most of the Thar Desert is situated in Rajasthan, covering 61% of its geographic area.

About 10 percent of this region consists of sand dunes, and the remaining 90 percent consist of craggy rock forms, compacted salt-lake bottoms, and interdunal and fixed dune areas. Annual temperatures can range from 0 °C (32 °F) in the winter to over 50 °C (122 °F) during the summer. Most of the rainfall received in this region is associated with the short July–September southwest monsoon that brings 100 to 500 mm (3.9 to 19.7 in) of precipitation. Water is scarce and occurs at great depths, ranging from 30 to 120 metres (98 to 394 ft) below the ground level.[50] Rainfall is precarious and erratic, ranging from below 120 mm (4.7 in) in the extreme west to 375 mm (14.8 in) eastward. The only river in this region is Luni. The soils of the arid region are generally sandy to sandy-loam in texture. The consistency and depth vary as per the topographical features. The low-lying loams are heavier may have a hard pan of clay, calcium carbonate or gypsum.

In western India, the Kutch region in Gujarat and Koyna in Maharashtra are classified as a Zone IV region (high risk) for earthquakes. The Kutch city of Bhuj was the epicentre of the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, which claimed the lives of more than 1,337 people and injured 166,836 while destroying or damaging near a million homes.[51] The 1993 Latur earthquake in Maharashtra killed 7,928 people and injured 30,000.[52] Other areas have a moderate to low risk of an earthquake occurring.[53]

Coastal plains

The Eastern Coastal Plain is a wide stretch of land lying between the Eastern Ghats and the oceanic boundary of India. It stretches from Tamil Nadu in the south to West Bengal in the east. The Mahanadi, Godavari, Kaveri, and Krishna rivers drain these plains. The temperature in the coastal regions often exceeds 30 °C (86 °F), and is coupled with high levels of humidity. The region receives both the northeast monsoon and southwest monsoon rains. The southwest monsoon splits into two branches, the Bay of Bengal branch and the Arabian Sea branch. The Bay of Bengal branch moves northwards crossing northeast India in early June. The Arabian Sea branch moves northwards and discharges much of its rain on the windward side of Western Ghats. Annual rainfall in this region averages between 1,000 and 3,000 mm (39 and 118 in). The width of the plains varies between 100 and 130 km (62 and 81 mi).[32] The plains are divided into six regions—the Mahanadi delta, the southern Andhra Pradesh plain, the Krishna-Godavari deltas, the Kanyakumari coast, the Coromandel Coast, and sandy coastal.[citation needed]

The Western Coastal Plain is a narrow strip of land sandwiched between the Western Ghats and the Arabian Sea, ranging from 50 to 100 km (31 to 62 mi) in width. It extends from Gujarat in the north and extends through Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, and Kerala. Numerous rivers and backwaters inundate the region. Mostly originating in the Western Ghats, the rivers are fast-flowing, usually perennial, and empty into estuaries. Major rivers flowing into the sea are the Tapti, Narmada, Mandovi and Zuari. Vegetation is mostly deciduous, but the Malabar Coast moist forests constitute a unique ecoregion. The Western Coastal Plain can be divided into two parts, the Konkan and the Malabar Coast.

Islands

The Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are India's two major island formations and are classified as union territories.

The Lakshadweep Islands lie 200 to 440 km (120 to 270 mi) off the coast of Kerala in the Arabian sea with an area of 32 km2 (12 sq mi). They consist of twelve atolls, three reefs, and five submerged banks, with a total of about 35 islands and islets.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are located between 6° and 14° north latitude and 92° and 94° east longitude.[54] They consist of 572 islands, lying in the Bay of Bengal near the Myanmar coast running in a north–south axis for approximately 910 km. They are located 1,255 km (780 mi) from Kolkata (Calcutta) and 193 km (120 mi) from Cape Negrais in Burma.[54] The territory consists of two island groups, the Andaman Islands and the Nicobar Islands. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands consist of 572 islands which run in a north–south axis for around 910 km. The Andaman group has 325 islands which cover an area of 6,170 km2 (2,380 sq mi) while the Nicobar group has only 247 islands with an area of 1,765 km2 (681 sq mi). India's only active volcano, Barren Island is situated here. It last erupted in 2017. The Narcondum is a dormant volcano and there is a mud volcano at Baratang. Indira Point, India's southernmost land point, is situated in the Nicobar islands at 6°45’10″N and 93°49’36″E, and lies just 189 km (117 mi) from the Indonesian island of Sumatra, to the southeast. The highest point is Mount Thullier at 642 m (2,106 ft).

Other significant islands in India include Diu, a former Portuguese colony; Majuli,[55] a river island of the Brahmaputra; Elephanta in Bombay Harbour; and Sriharikota, a barrier island in Andhra Pradesh. Salsette Island is India's most populous island on which the city of Mumbai (Bombay) is located. Forty-two islands in the Gulf of Kutch constitute the Marine National Park.

Natural resources

Major resource-based industries of India are fisheries, agriculture, mining, and petroleum products . India has the 18th-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world with a total size of 2,305,143 km2 (890,021 sq mi). It includes the Lakshadweep island group in the Laccadive Sea off the southwestern coast of India and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

Ecological resources

India was ranked seventh among the list of countries most affected by climate change in 2019.[56] Temperature rises on the Tibetan Plateau are causing Himalayan glaciers to retreat, threatening the flow rate of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, Yamuna and other major rivers. A 2007 World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) report states that the Indus River may run dry for the same reason.[57] Severe landslides and floods are projected to become increasingly common in such states as Assam.[58] Temperatures in India have risen by 0.7 °C (1.3 °F) between 1901 and 2018.[59] According to some current projections, the number and severity of droughts in India will have markedly increased by the end of the present century.[60] Ecological disasters, such as a 1998 coral bleaching event that killed off more than 70% of corals in the reef ecosystems off Lakshadweep and the Andamans and was brought on by elevated ocean temperatures tied to global warming, are also projected to become increasingly common.[61][62]

Water bodies

India has around 14,500 km of inland navigable waterways.[63] There are twelve rivers which are classified as major rivers, with the total catchment area exceeding 2,528,000 km2 (976,000 sq mi).[28] All major rivers of India originate from one of the three main watersheds:[28]

- The Himalaya and the Karakoram ranges

- Vindhya and Satpura range in central India

- Sahyadri or Western Ghats in western India

The Himalayan river networks are snow-fed and have a perennial supply throughout the year. The other two river systems are dependent on the monsoons and shrink into rivulets during the dry season. The Himalayan rivers that flow westward into Punjab are the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.[64]

The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghana system has the largest catchment area of about 1,600,000 km2 (620,000 sq mi).[65] The Ganges Basin alone has a catchment of about 1,100,000 km2 (420,000 sq mi).[28] The Ganges originates from the Gangotri Glacier in Uttarakhand.[64] It flows southeast, draining into the Bay of Bengal.[28] (The Yamuna and Gomti rivers also arise in the western Himalayas and join the Ganges in the plains.[28] The Brahmaputra originates in Tibet, China, where it is known as the Yarlung Tsangpo River) (or "Tsangpo"). It enters India in the far-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, then flows west through Assam. The Brahmaputra merges with the Ganges in Bangladesh, where it is known as the Jamuna River.[28][66]

The Chambal, another tributary of the Ganges, via the Yamuna, originates from the Vindhya-Satpura watershed. The river flows eastward. Westward-flowing rivers from this watershed are the Narmada and Tapi, which drain into the Arabian Sea in Gujarat. The river network that flows from east to west constitutes 10% of the total outflow.[clarification needed]

(The Western Ghats are the source of all Deccan rivers, which include the through Godavari River, Krishna River and Kaveri River, all draining into the Bay of Bengal. These rivers constitute 20% of India's total outflow).[64]

The heavy southwest monsoon rains cause the Brahmaputra and other rivers to distend their banks, often flooding surrounding areas. Though they provide rice paddy farmers with a largely dependable source of natural irrigation and fertilisation, such floods have killed thousands of people and tend to cause displacements of people in such areas.

Major gulfs include the Gulf of Cambay, Gulf of Kutch, and the Gulf of Mannar. Straits include the Palk Strait, which separates India from Sri Lanka; the Ten Degree Channel, which separates the Andamans from the Nicobar Islands; and the Eight Degree Channel, which separates the Laccadive and Amindivi Islands from the Minicoy Island to the south. Important capes include the Kanyakumari (formerly called Cape Comorin), the southern tip of mainland India; Indira Point, the southernmost point in India (on Great Nicobar Island); Rama's Bridge, and Point Calimere. The Arabian Sea lies to the west of India, the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean lie to the east and south, respectively. Smaller seas include the Laccadive Sea and the Andaman Sea. There are four coral reefs in India, located in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Gulf of Mannar, Lakshadweep, and the Gulf of Kutch.[67] Important lakes include Sambhar Lake, the country's largest saltwater lake in Rajasthan, Vembanad Lake in Kerala, Kolleru Lake in Andhra Pradesh, Loktak Lake in Manipur, Dal Lake in Kashmir, Chilka Lake (lagoon lake) in Odisha, and Sasthamkotta Lake in Kerala.

Wetlands

India's wetland ecosystem is widely distributed from the cold and arid located in the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir, and those with the wet and humid climate of peninsular India. Most of the wetlands are directly or indirectly linked to river networks. The Indian government has identified a total of 71 wetlands for conservation and are part of sanctuaries and national parks.[68] Mangrove forests are present all along the Indian coastline in sheltered estuaries, creeks, backwaters, salt marshes and mudflats. The mangrove area covers a total of 4,461 km2 (1,722 sq mi),[69] which comprises 7% of the world's total mangrove cover. Prominent mangrove covers are located in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Sundarbans delta, the Gulf of Kutch and the deltas of the Mahanadi, Godavari and Krishna rivers. Parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Kerala also have large mangrove covers.[67]

The Sundarbans delta is home to the largest mangrove forest in the world. It lies at the mouth of the Ganges and spreads across areas of Bangladesh and West Bengal. The Sundarbans is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but is identified separately as the Sundarbans (Bangladesh) and the Sundarbans National Park (India). The Sundarbans are intersected by a complex network of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The area is known for its diverse fauna, being home to a large variety of species of birds, spotted deer, crocodiles and snakes. Its most famous inhabitant is the Bengal tiger. It is estimated that there are now 400 Bengal tigers and about 30,000 spotted deer in the area.

The Rann of Kutch is a marshy region located in northwestern Gujarat and the bordering Sindh province of Pakistan. It occupies a total area of 27,900 km2 (10,800 sq mi).[70] The region was originally a part of the Arabian Sea. Geologic forces such as earthquakes resulted in the damming up of the region, turning it into a large saltwater lagoon. This area gradually filled with silt thus turning it into a seasonal salt marsh. During the monsoons, the area turn into a shallow marsh, often flooding to knee-depth. After the monsoons, the region turns dry and becomes parched.

Arable land

India's arable land area of 1,597,000 km2 (394.6 million acres) is the second largest in the world, after the United States. Its gross irrigated crop area of 826,000 km2 (215.6 million acres) is the largest in the world, followed by US and China.[71] Of the 160 million hectares of cultivated land in India, about 39 million hectare can be irrigated by groundwater wells and an additional 22 million hectares by irrigation canals.[72] In 2010, only about 35% of agricultural land in India was reliably irrigated.[73] About 2/3rd cultivated land in India is dependent on monsoons.[74]

Economic resources

Minerals and ores

India is the world's biggest producer of mica blocks and mica splittings.[75] India ranks second amongst the world's largest producers of barite and chromite.[75] The Pleistocene system is rich in minerals. India is the third-largest coal producer in the world and ranks fourth in the production of iron ore.[76][75] It is the fifth-largest producer of bauxite, second largest of crude steel as of February 2018 replacing Japan, the seventh-largest of manganese ore and the eighth-largest of aluminium.[75] India has significant sources of titanium ore, diamonds and limestone.[77] India possesses 24% of the world's known and economically viable thorium, which is mined along shores of Kerala.[78] Gold had been mined in the now-defunct Kolar Gold Fields in Karnataka.[79]

Renewable water

India's total renewable water resources are estimated at 1,907.8 km3 a year.[80] Its annual supply of usable and replenishable groundwater amounts to 350 billion cubic metres.[81] Only 35% of groundwater resources are being utilised.[81] About 44 million tonnes of cargo is moved annually through the country's major rivers and waterways.[63] Groundwater supplies 40% of water in India's irrigation canals. 56% of the land is arable and used for agriculture. Black soils are moisture-retentive and are preferred for dry farming and growing cotton, linseed, etc. Forest soils are used for tea and coffee plantations. Red soils have a wide diffusion of iron content.[82]

Energy

Most of India's estimated 5.4 billion barrels (860,000,000 m3) in oil reserves are located in the Mumbai High, upper Assam, Cambay, the Krishna-Godavari and Cauvery basins.[76] India possesses about seventeen trillion cubic feet of natural gas in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat and Odisha.[76] Uranium is mined in Andhra Pradesh. India has 400 medium-to-high enthalpy thermal springs for producing geothermal energy in seven areas—the Himalayas, Sohana, Cambay, the Narmada-Tapti delta, the Godavari delta and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (specifically the volcanic Barren Island.)[83]

Climate

Based on the Köppen system, India hosts six major climatic subtypes, ranging from arid desert in the west, alpine tundra and glaciers in the north, and humid tropical regions supporting rainforests in the southwest and the island territories. The nation has four seasons: winter (January–February), summer (March–May), a monsoon (rainy) season (June–September) and a post-monsoon period (October–December).[64]

The Himalayas act as a barrier to the frigid katabatic winds flowing down from Central Asia. Thus, northern India is kept warm or only mildly cooled during winter; in summer, the same phenomenon makes India relatively hot. Although the Tropic of Cancer—the boundary between the tropics and subtropics—passes through the middle of India, the whole country is considered to be tropical.[85]

Summer lasts between March and June in most parts of India. Temperatures can exceed 40 °C (104 °F) during the day. The coastal regions exceed 30 °C (86 °F) coupled with high levels of humidity. In the Thar desert area temperatures can exceed 45 °C (113 °F). The rain-bearing monsoon clouds are attracted to the low-pressure system created by the Thar Desert. The southwest monsoon splits into two arms, the Bay of Bengal arm and the Arabian Sea arm. The Bay of Bengal arm moves northwards crossing northeast India in early June. The Arabian Sea arm moves northwards and deposits much of its rain on the windward side of Western Ghats. Winters in peninsula India see mild to warm days and cool nights. Further north the temperature is cooler. Temperatures in some parts of the Indian plains sometimes fall below freezing. Most of northern India is plagued by fog during this season. The highest temperature recorded in India was 51 °C (124 °F) in Phalodi, Rajasthan.[86] And the lowest was −60 °C (−76 °F) in Dras, Jammu and Kashmir.[87]

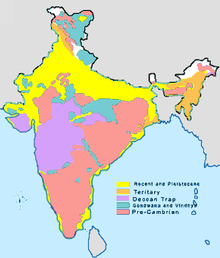

Geology

India's geological features are classified based on their era of formation.[88] The Precambrian formations of Cudappah and Vindhyan systems are spread out over the eastern and southern states. A small part of this period is spread over western and central India.[88] The Paleozoic formations from the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian system are found in the Western Himalaya region in Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh.[88] The Mesozoic Deccan Traps formation is seen over most of the northern Deccan; they are believed to be the result of sub-aerial volcanic activity.[88] The Trap soil is black in colour and conducive to agriculture. The Carboniferous system, Permian System and Triassic systems are seen in the western Himalayas. The Jurassic system is seen in the western Himalayas and Rajasthan.

Tertiary imprints are seen in parts of Manipur, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and along the Himalayan belt. The Cretaceous system is seen in central India in the Vindhyas and part of the Indo-Gangetic plains.[88] The Gondwana system is seen in the Narmada River area in the Vindhyas and Satpuras. The Eocene system is seen in the western Himalayas and Assam. Oligocene formations are seen in Kutch and Assam.[88] The Pleistocene system is found over central India. The Andaman and Nicobar Island are thought to have been formed in this era by volcanoes.[88] The Himalayas were formed by the convergence and deformation of the Indo-Australian and Eurasian Plates. Their continued convergence raises the height of the Himalayas by one centimetre each year.

Soils in India can be classified into eight categories: alluvial, black, red, laterite, forest, arid and desert, saline and alkaline and peaty and organic soils.[89][90] Alluvial soil constitute the largest soil group in India, constituting 80% of the total land surface.[90] It is derived from the deposition of silt carried by rivers and are found in the Great Northern plains from Punjab to the Assam valley.[90] Alluvial soil are generally fertile but they lack nitrogen and tend to be phosphoric.[90] National Disaster Management Authority says that 60% of Indian landmass is prone to earthquakes and 8% susceptible to cyclone risks.

Black soil are well developed in the Deccan lava region of Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh.[82] These contain high percentage of clay and are moisture retentive.[90] Red soils are found in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka plateau, Andhra plateau, Chota Nagpur plateau and the Aravallis.[82] These are deficient in nitrogen, phosphorus and humus.[90][82] Laterite soils are formed in tropical regions with heavy rainfall. Heavy rainfall results in leaching out all soluble material of top layer of soil. These are generally found in Western ghats, Eastern ghats and hilly areas of northeastern states that receive heavy rainfall. Forest soils occur on the slopes of mountains and hills in Himalayas, Western Ghats and Eastern Ghats. These generally consist of large amounts of dead leaves and other organic matter called humus.

Cratons

Cratons are a specific kind of continental crust made up of a top layer called platform and an older layer called basement. A shield is the part of a craton where basement rock crops out of the ground, and it is relatively the older and more stable section, unaffected by plate tectonics.[91][92]

The Indian Craton can be divided into five major cratons as such:

- Aravalli Craton (Marwar-Mewar Craton or Western Indian Craton): Covers Rajasthan as well as western and southern Haryana. It comprises Mewar Craton in the east and Marwar Craton in the west. It is limited by the Great Boundary Fault in the east, sandy Thar Desert in the Thar desert in the west, Indo-ganetic alluvium in the north, Son-Narmada-Tapti in the south. It mainly has quartzite, marble, pelite, greywacke and extinct volcanos exposed in Aravalli-Delhi Orogen. Malani Igneous Suite is the largest in India and third largest igneous suite in the world.

- Bundelkand Craton, covers 26,00 km2 in the Bundelkhand region of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh and forms the basis of the Malwa Plateau. It is limited by the Aravalli in the west, Narmada river and Satpura range in the south, and Indo-Gantetic alluvium in the north. It is similar to the Aravali Craton, which used to be a single craton before being divided into two with the evolution of Hindoli and Mahakoshal belts at the margins of two cratons.

- Dharwar Craton (Karnataka Craton), 3.4 - 2.6 Ga, granite-greenstone terrain covers the state of Karnataka and parts of eastern and southern Maharashtra state, and forms the basis of the southern end of the Deccan Plateau. In 1886 it was divided into two tectonic blocks, namely Eastern Dharwar Craton (EDC) and Western Dharwar Craton (WDC).

- Singhbhum Craton, 4,000 km2 area which primarily covers Jharkhand as well as parts of Odisha, northern Andhra Pradesh, northern Telangana and eastern Maharashtra. It is limited by the Chhota Nagpur Plateau to the north, Eastern Ghats to the southeast, Bastar Craton to southwest and alluvium plain to the east.

- Bastar Craton (Bastar-Bhandara Craton), primarily covers Chhattisgarh and forms the basis of the Chhota Nagpur Plateau. It is a remnant of 3.4-3.0 Ga old TTG gneisses of five types. It is subdivided into Kotri-Dongagarh Orogen and the Rest of Bastar Craton. It is limited by three rifts, Godavari rift in southwest, Narmada rift in northwest and Mahanadi rift in northeast.

See also

- Geology of India

- Borders of India

- Climate change in India

- Disputed territories of India

- List of extreme points of India

- Exclusive economic zone of India

- List of disputed territories of India

- Outline of India

- Category:Lists of villages in India

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Annual Report 2016-17, Ministry of Home Affairs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ India Yearbook, p. 1

- ^ "India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2012. Total area includes disputed territories not under Indian control.

- ^ "India at a Glance: Area". Ministry of Home Affairs: Government of India. 2001. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Jammu and Kashmir - CIA" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – The Country)". Manorama Year Book. Malayala Manorama: 515. 2006. ISSN 0542-5778.

- ^ "Territorial extent of India's waters". The International Law of the Sea and Indian MaritimeLegislation. 30 April 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

- ^ Zhu, Bin; et al. Age of Initiation of the India-Asia Collision in the East-Central Himalaya (PDF). Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University at Albany. p. 281. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ a b Kind, Rainer (September 2007). "The Fastest Continent: India's truncated lithospheric roots". Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ DelhiAugust 5. "States and Union Territories". Know India Programme. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/BM_MAN-IN-PAKS-060513.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/BM_MAN-IN-BANG-270813.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Naunidhi Kaur (June 2002). "The Nowhere People". Frontline Magazine, the Hindu. 19 (12). Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "India, Bangladesh ratify historic land deal, Narendra Modi announces new $2 billion line of credit to Dhaka". The Times of India. 6 June 2015. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Daniyal, Shoaib (8 May 2015). "India-Bangla land swap: was the world's strangest border created by a game of chess?". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Another Chinese intrusion in Sikkim". Oneindia.in. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/Indo-Myanmar-1011.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/Indo-Bhutan-1011.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/Indo-Nepal-270813.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Baker, Kathleen M.; Chapman, Graham P. (11 March 2002), The Changing Geography of Asia, Routledge, pp. 10–, ISBN 978-1-134-93384-6,

This greater India is well defined in terms of topography; it is the Indian sub-continent, hemmed in by the Himalayas on the north, the Hindu Khush in the west and the Arakanese in the east.

- ^ Measurements are from recent imagery, generally supplemented with Russian 1:200,000 scale topographic mapping as well as Jerzy Wala, Orographical Sketch Map: Karakoram: Sheets 1 & 2, Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich, 1990.

- ^ "Physical divisions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2004.

- ^ Dale Hoiberg; Indu Ramchandani (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- ^ Gupta, Harsh K; Aloka Parasher-Sen; Dorairajan Balasubramanian (2000). Deccan Heritage. Orient Blackswan. p. 28. ISBN 81-7371-285-9.

- ^ Sharma, Hari Shanker (1987). Tropical geomorphology: a morphogenetic study of Rajasthan. Concept. p. 295. ISBN 81-7022-041-6.

- ^ a b c "Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – The Country)". Manorama Year Book. Malayala Manorama: 516. 2006. ISSN 0542-5778.

- ^ The Indian geographical journal. Vol. 46. Indian Geographical Society. 1971. p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – The Country). p. 517.

- ^ "The Deccan Plateau". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ Ghati meaning, Hindi-English Collins dictionary.

- ^ Navneet Marathi English Dictionary. Mumbai 400028: Navneet Publications (India) Limited. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b "The Eastern Coastal Plain". Rainwaterharvesting.org. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Western Ghats". Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Clayton, Pamela (November 2006). "Introduction". Literacy in Kerala. Hindimetyari. ISBN 0-86389-068-7. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; Da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–858. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..853M. doi:10.1038/35002501. PMID 10706275. S2CID 4414279.

- ^ "UN designates Western Ghats as world heritage site". The Times of India. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Migon, Piotr (12 May 2010). Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer. p. 257. ISBN 978-90-481-3054-2.

- ^ A biodiversity hotspot, archived from the original on 18 January 2019, retrieved 5 September 2023

- ^ "Western Ghats". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Clara (3 July 2012). "39 sites in Western Ghats get world heritage status". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ >Bombay Teachers and the Cultural Role of Cities Archived 5 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Page 110.

- ^ Of 'ghati', 'bhaiyya' & 'yandu gundu': Mumbai has huge diversity in its pejoratives Archived 5 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, First Post, 26 Feb 2019.

- ^ Guruprasad Datar, 2018, Stereotypes Archived 5 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine,

- ^ Pullaiah, Thammineni; D.Muralidhara Rao (2002). "Preface". Flora of Eastern Ghats: Hill ranges of south east India. Vol. 1. Daya Books. p. 1. ISBN 81-87498-49-8.

- ^ Kenneth Pletcher (2010). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 978-16-1530-142-3.

- ^ Sriramadas, A. (November 1967). "Geology of Eastern Ghats in Andhra Pradesh" (PDF). Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, Section B. 66 (5): 200–205. doi:10.1007/BF03052185. S2CID 126925893.

- ^ "Geography Now! India". Youtube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- ^ "The World's Largest Desert". geology.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ "Thar Desert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 May 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ Kaul, R.N. (1970). Afforestation in Arid zones. N.V. Publishers, The Hague.

- ^ "Preliminary Earthquake Report". USGS Earthquake Hazards Program. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ^ Brijesh Gulati (January 2006). Earthquake Risk Assessment of Buildings: Applicability of HAZUS in Dehradun, India (PDF) (MS thesis). International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – The Country). p. 519.

- ^ a b "National Portal of India: Know India: State of UTs". Government of India. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ Majuli, River Island. "Largest river island". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Eckstein, David; Künzel, Vera; Schäfer, Laura (January 2021). "Global Climate Risk Index 2021" (PDF). GermanWatch.org.

- ^ "How climate change hits India's poor". BBC News. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Warmer Tibet can see Brahmaputra flood Assam | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Sharma, Vibha (15 June 2020). "Average temperature over India projected to rise by 4.4 degrees Celsius: Govt report on impact of climate change in country". Tribune India. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Gupta, Vivek; Jain, Manoj Kumar (2018). "Investigation of multi-model spatiotemporal mesoscale drought projections over India under climate change scenario". Journal of Hydrology. 567: 489–509. Bibcode:2018JHyd..567..489G. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.10.012. ISSN 0022-1694. S2CID 135053362.

- ^ Normile, D. (12 May 2000). "GLOBAL WARMING:Some Coral Bouncing Back From El Niño". Science. 288 (5468): 941a–942. doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.941a. PMID 10841705. S2CID 128503395.

- ^ Aggarwal, D., Lal, M. Vulnerability of the Indian Coastline to Sea Level Rise (SURVAS Flood Hazard Research Centre)

- ^ a b "Introduction to Inland Water Transport". Government of India. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – The Country). p. 518.

- ^ Elhance, Arun P. (1999). Hydropolitics in the Third World: conflict and cooperation in international river basins. US Institute of Peace Press. pp. 156–158. ISBN 978-1-878379-91-7.

- ^ Brahmaputra River Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – Environment). p. 580.

- ^ India Yearbook, p. 306

- ^ India Yearbook, p. 309

- ^ World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Rann of Kutch". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ "India outranks US, China with world's highest net cropland area". Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Global map of irrigated areas: India Archived 23 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine FAO-United Nations and Bonn University, Germany (2013)

- ^ Agricultural irrigated land (% of total agricultural land) The World Bank (2013)

- ^ Economic Times: How to solve the problems of India's rain-dependent agricultural land

- ^ a b c d "India's Contribution to the World's Mineral Production". Ministry of Mines, Government of India. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ a b c "Energy profile of India". Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ "India". CIA Factbook. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2007.

- ^ "Information and Issue Briefs – Thorium". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- ^ "Death of the Kolar Gold Fields". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Water profile of India". Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ a b Jain, J.K.; Farmer, B. H.; Rush, H.; West, H. W.; Allan, J. A.; Dasgupta, B.; Boon, W. H. (May 1977). "India's Underground Water Resources". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 278 (962): 507–22. Bibcode:1977RSPTB.278..507J. doi:10.1098/rstb.1977.0058.

- ^ a b c d "Krishi World website". Krishiworld.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ Chandrasekharam, D. "Geothermal Energy Resources of India". Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (direct: Final Revised Paper) - ^ Climate Change: Myths and Realities. Jeevananda Reddy. p. 65. GGKEY:WDFHBL1XHK3.

- ^ "India sets new heat record as temperatures soar". Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Binayak, Poonam (30 August 2017). "Dras: The World's Second Coldest Inhabited Place". Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Manorama Yearbook 2006 (India – Geology). p. 521.

- ^ "India Agronet – Soil Management". Indiagronet.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fertilizer use by crop in India". U.S. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Cratons of India Archived 12 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cratons of India Archived 16 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, lyellcollection.org.

Bibliography

- India Yearbook 2007. Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Govt. Of India. 2007. ISBN 978-81-230-1423-4.

Further reading

- Singh, R.L. (1971). India A Regional Geography. National Geographical Society of India. ISBN 978-8185273181. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Nag, Prithvish; Sengupta, Smita (1992). Geography of India. Concept Publishing Co. ISBN 978-8170223849.

- Spate, O.H.K.; Learmonth, A.T.A. (1967). India and Pakistan: A General and Regional Geography. Methuen Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1138290723.

- Pal, Saroj K. (1998). Physical Geography of India: A Study in Regional Earth Sciences. Sangam Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0863117510.

- Kale, Vishwas S. (2014). Landscapes and Landforms of India (World Geomorphological Landscapes). Springer. ISBN 978-9402400298.

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (2015). The Incredible History of India's Geography. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0143333661.

- Balfour, E (1976). Encyclopaedia Asiatica: Comprising Indian Subcontinent, Eastern and Southern Asia. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 81-7020-325-2.

- Allaby, M (1998). Floods. Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-3520-2.

- Nash, JM (2002). El Niño: Unlocking the Secrets of the Master Weather Maker. Warner. ISBN 0-446-52481-6.

- "Land and Natural Resources". Terrain. Archived from the original on 22 February 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2005.