Wee1

| Wee1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

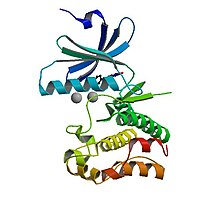

Crystal structure of human Wee1 | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | Mitosis inhibitor protein kinase Wee1 | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | wee1 dual specificity protein kinase Wee1 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 2539123 | ||||||

| UniProt | P07527 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 2.7.11.1 | ||||||

| |||||||

Wee1 is a nuclear kinase belonging to the Ser/Thr family of protein kinases in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S. pombe). Wee1 has a molecular mass of 96 kDa and is a key regulator of cell cycle progression.[1]

It influences cell size by inhibiting the entry into mitosis, through inhibiting Cdk1. Wee1 has homologues in many other organisms, including mammals.[citation needed]

Introduction

[edit]The regulation of cell size is critical to ensure functionality of a cell. Besides environmental factors such as nutrients, growth factors and functional load, cell size is also controlled by a cellular cell size checkpoint.[citation needed]

Wee1 is a component of this checkpoint. It is a kinase determining the timepoint of entry into mitosis, thus influencing the size of the daughter cells. Loss of Wee1 function will produce smaller than normal daughter cell, because cell division occurs prematurely.[citation needed]

Its name is derived from the Scottish dialect word wee, meaning small - its discoverer Paul Nurse was working at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland at the time of discovery.[2][3]

Discovery / History

[edit]The discovery of the Wee1 gene is accredited to Paul Nurse, who first identified it in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) in 1978. In his initial experiments, Nurse demonstrated Wee1 to be a negative regulator of mitosis, such that Wee1+ activity was critical in preventing premature mitosis in Cdc25+ (a mitotic inducer) yeast cells and increased Wee1+ expression could further delay cell cycle progression until cells grew to be larger in size.[4] Following this data, Nurse, together with Pierre Thuriaux, analyzed fifty two Wee mutants undergoing mitosis – those lacking in Wee1 were comparatively smaller; their analysis led them to a model (later demonstrated to be true) where Wee1 is a dosage-dependent inhibitor of Cdc2, whose activity is required for a cell’s entry into M phase.[5][3] As a result of these discoveries and its contributions to our understanding of cell cycle control, Nurse went on to win the 2001 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology (shared also with Lee Hartwell and Tim Hunt).[6]

Wee1 is part of a family of three serine/threonine protein kinases, consisting of Wee1 (also known as WEE1A), PKMYT1, and Wee2 (WEE1B).[7] These three kinases have similar sequences in their respective kinase domains, but exhibit differences in their localization, regulation, and activation patterns. PKMYT1 is the only one of the three that is not typically found in the nucleus, but rather, is associated with the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and golgi apparatus.[8] And while Wee1 and PKMYT1 both play critical roles in regulating entry into mitosis (i.e. working together to inhibit Cdk1 as it moves in / out of the cell nucleus), WEE1B was first discovered in Xenopus oocytes and is most active at the metaphase II exit point of meiosis prior to fertilization.[7][9] Additionally, WEE1B is not as well-researched in the field of oncology as compared to its family members (both of which have better understood roles in cancer development), as there does not seem to be much evidence supporting WEE1B’s role in tumorigenesis.

Function

[edit]

Wee1 inhibits Cdk1 by phosphorylating it on two different sites, Tyr15 and Thr14.[10] Cdk1 is crucial for the cyclin-dependent passage of the various cell cycle checkpoints. At least three checkpoints exist for which the inhibition of Cdk1 by Wee1 is important:

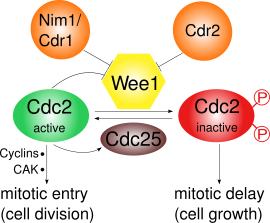

- G2/M checkpoint: Wee1 phosphorylates the amino acids Tyr15 and Thr14 of Cdk1, which keeps the kinase activity of Cdk1 low and prevents entry into mitosis; in S. pombe further cell growth can occur. Wee1 mediated inactivation of Cdk1 has been shown to be ultrasensitive as a result of substrate competition.[11] During mitotic entry the activity of Wee1 is decreased by several regulators and thus Cdk1 activity is increased. In S. pombe, Pom1, a protein kinase, localizes to the cell poles. This activates a pathway in which Cdr2 inhibits Wee1 through Cdr1. Cdk1 itself negatively regulates Wee1 by phosphorylation, which leads to a positive feedback loop. The decreased Wee1 activity alone is not sufficient for mitotic entry: Synthesis of cyclins and an activating phosphorylation by a Cdk activating kinase (CAK) are also required.[12]

- Cell size checkpoint: There is evidence for the existence of a cell size checkpoint, which prevents small cells from entering mitosis. Wee1 plays a role in this checkpoint by coordinating cell size and cell cycle progression.[13]

- DNA damage checkpoint: This checkpoint also controls the G2/M transition. In S. pombe this checkpoint delays the mitosis entry of cells with DNA damage (for example induced by gamma radiation). The lengthening of the G2 phase depends on Wee1; wee1 mutants have no prolonged G2 phase after gamma irradiation.[14]

Epigenetic function of Wee1 kinase has also been reported. Wee1 was shown to phosphorylate histone H2B at tyrosine 37 residue which regulated global expression of histones.[15] [16]

Homologues

[edit]| human WEE1 homolog (S. pombe) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | WEE1 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 7465 | ||||||

| HGNC | 12761 | ||||||

| OMIM | 193525 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_003390 | ||||||

| UniProt | P30291 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 11 p15.3-15.1 | ||||||

| |||||||

| human WEE1 homolog 2 (S. pombe) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | WEE2 | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 494551 | ||||||

| HGNC | 19684 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_001105558 | ||||||

| UniProt | P0C1S8 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 7 q32-q32 | ||||||

| |||||||

The WEE1 gene has two known homologues in humans, WEE1 (also known as WEE1A) and WEE2 (WEE1B). The corresponding proteins are Wee1-like protein kinase and Wee1-like protein kinase 2 which act on the human Cdk1 homologue Cdk1.

The homologue to Wee1 in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is called Swe1.

Regulation

[edit]In S. pombe, Wee1 is phosphorylated

Cdk1 and cyclin B make up the maturation promoting factor (MPF) which promotes the entry into mitosis. It is inactivated by phosphorylation through Wee1 and activated by the phosphatase Cdc25C. Cdc25C in turn is activated by Polo kinase and inactivated by Chk1.[13] Thus in S. pombe Wee1 regulation is mainly under the control of phosphorylation through the polarity kinase, Pom1's, pathway including Cdr2 and Cdr1.[17][18][19][20]

At the G2/M transition, Cdk1 is activated by Cdc25 through dephosphorylation of Tyr15. At the same time, Wee1 is inactivated through phosphorylation at its C-terminal catalytic domain by Nim1/Cdr1.[19] Also, the active MPF will promote its own activity by activating Cdc25 and inactivating Wee1, creating a positive feedback loop, though this is not yet understood in detail.[13]

Higher eukaryotes regulate Wee1 via phosphorylation and degradation

In higher eukaryotes, Wee1 inactivation occurs both by phosphorylation and degradation.[21]

The protein complex[nb 1] SCFβ-TrCP1/2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that functions in Wee1A ubiquitination. The M-phase kinases Polo-like kinase (Plk1) and Cdc2 phosphorylate two serine residues in Wee1A which are recognized by SCFβ-TrCP1/2.[22]

S. cerevisiae homologue Swe1

In S. cerevisiae, cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28 (Cdk1 homologue) is phosphorylated by Swe1 (Wee1 homologue) and dephosphorylated by Mih1 (Cdc25 homologue). Nim1/Cdr1 homologue in S. cerevisiae, Hsl1, together with its related kinases Gin4 and Kcc4 localize Swe1 to the bud-neck. Bud-neck associating kinases Cla4 and Cdc5 (polo kinase homologue) phosphorylate Swe1 at different stages of the cell cycle. Swe1 is also phosphorylated by Clb2-Cdc28 which serves as a recognition for further phosphorylation by Cdc5.

The S. cerevisiae protein Swe1 is also regulated by degradation. Swe1 is hyperphosphorylated by Clb2-Cdc28 and Cdc5 which may be a signal for ubiquitination and degradation by SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase complex as in higher eukaryotes.[23]

Role in cancer

[edit]The mitosis promoting factor MPF also regulates DNA-damage induced apoptosis. Negative regulation of MPF by WEE1 causes aberrant mitosis and thus resistance to DNA-damage induced apoptosis. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) negatively regulates human WEE1, thus increasing sensitivity to DNA-damage induced apoptosis in cancer cells.[24]

Wee1 as a target in oncology

[edit]Wee1 expression in tumors

[edit]While multiple studies have examined the relationship between Wee1 expression and tumors, there is not a strong consensus on whether Wee1 acts as an oncogene or a tumor suppressor in cancer tissues. In some cases, studies have reported an observed overexpression of Wee1 in solid tumors / cancers like glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, and more, as well as an association between elevated Wee1 expression and negative prognostic factors such as chemotherapy / radiotherapy resistance or other proliferation biomarkers; there are also accounts on an increased prevalence of upregulated Wee1 in instances there is also p53 loss of function. However, there are other reports which show occurrences of Wee1 downregulation (or a complete lack thereof) in cancer tissues such as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colon cancer, etc. Moreover, in certain cancers like breast cancer, there are conflicting / controversial reports.[25][7][26] Taken together, this discussion may signal that the application and manipulation of Wee1 will likely be situation-dependent.

Wee1 is very rarely mutated in cancer patients, with mutations seen at an overall frequency of around 1.2%. There is little data on how mutations affect tumor progression.[7]

Wee1 inhibitors

[edit]Wee1 inhibition has been a growing therapeutic area of interest. Contrary to perhaps the typical rationale behind using inhibitor drugs to trigger cell cycle arrest, Wee1 inhibitors instead disrupt the S / G2 checkpoints to prematurely induce mitosis in cells; this mechanism thus promotes a phenomenon called “mitotic catastrophe” – increased DNA damage (insufficient repair or new events such as double-stranded breaks) that ultimately lead to apoptosis.[27] At the cellular level, inhibiting Wee1 significantly reduces the presence of Tyr15, which consequently allows for Cdk1 kinase activity to build up and trigger entry into mitosis.[7]

Clinical development

[edit]To date, there have not been many Wee1 inhibitors developed and at the clinical stage. Adavosertib (AZD1775, MK1755), developed by AstraZeneca, is a small molecule Wee1 inhibitor, and was the first of its kind to reach clinical trials.[28] Although in 2022, the company itself removed the drug from its pipeline, multiple trials testing adavosertib as both a monotherapy or in combination were conducted. Results from randomized phase II trial FOCUS4-C demonstrated an around 2 month progression-free survival (PFS) improvement in those treated with adavosertib alone (versus the active monitoring control group);[29] meanwhile, another trial evaluating the efficacy of adavosertib in both patients with solid tumors and clear cell renal cell carcinoma observed no objective responses (with stable disease as the best response in 10/18 enrolled patients).[30] Other studies examining the effect of adavosertib in combination with other treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, etc.) saw varying levels of impact, with the most promising data coming from trials for gynecological cancer patients. In one phase II trial using the Wee1 inhibitor in combination with carboplatin (a chemotherapy drug) in p53-mutated ovarian cancer patients, an overall response rate of 41% and median PFS of 5.6 months was observed;[31] another combining gemcitabine (also a chemotherapy drug) and adavosertib in recurrent ovarian cancer patients reported a significant improvement in PFS (4.6 months in the treatment group vs. 3.0 months in the placebo group).[32] It seems that a major contributor to the halt / limited continued development of adavosertib is its toxicity; several of the aforementioned studies cited patients experiencing Grade 3+ adverse events including anemia, gastrointestinal toxicities, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and more.

Five other Wee1 inhibitors (ZN-c3, Debio-0123, SY-4835, ACR-2316, and IMP7086) are still actively under clinical evaluation. Phase I data for ZN-c3 (azenosertib, developed by Zentalis Therapeutics) shows early signs of clinical activity (2 partial responses and 5 stable disease out of 16 dosed patients) and tolerability;[33] however, several azenosertib trials were temporarily placed on clinical hold by the FDA between June and September 2024 after two patient deaths occurred.[34]

Mutant phenotype

[edit]Wee1 acts as a dosage-dependent inhibitor of mitosis.[35] Thus, the amount of Wee1 protein correlates with the size of the cells:

The fission yeast mutant wee1, also called wee1−, divides at a significantly smaller cell size than wildtype cells. Since Wee1 inhibits entry into mitosis, its absence will lead to division at a premature stage and sub-normal cell size. Conversely, when Wee1 expression is increased, mitosis is delayed and cells grow to a large size before dividing.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ β-transducin repeat-containing protein 1/2 (β-TrCP1/2) F-box protein-containing SKP1/Cul1/F-box protein complex

References

[edit]- ^ "Gene: wee1 / SPCC18B5.03". PomBase.

- ^ Nurse P (December 2004). "Wee beasties". Nature. 432 (7017): 557. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..557N. doi:10.1038/432557a. PMID 15577889.

- ^ a b Nurse P, Thuriaux P (November 1980). "Regulatory genes controlling mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe". Genetics. 96 (3): 627–37. doi:10.1093/genetics/96.3.627. PMC 1214365. PMID 7262540.

- ^ Russell P, Nurse P (May 1987). "Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog". Cell. 49 (4): 559–567. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2. PMID 3032459.

- ^ Murray A (December 2016). "Paul Nurse and Pierre Thuriaux on wee Mutants and Cell Cycle Control". Genetics. 204 (4): 1325–1326. doi:10.1534/genetics.116.197186. PMC 5161264. PMID 27927897.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2001".

- ^ a b c d e Ghelli Luserna di Rorà A, Cerchione C, Martinelli G, Simonetti G (December 2020). "A WEE1 family business: regulation of mitosis, cancer progression, and therapeutic target". Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 13 (1): 126. doi:10.1186/s13045-020-00959-2. PMC 7507691. PMID 32958072.

- ^ "PKMYT1 in Cell Cycle Regulation and Cancer Therapeutics". 5 March 2024.

- ^ Esposito F, Giuffrida R, Raciti G, Puglisi C, Forte S (October 2021). "Wee1 Kinase: A Potential Target to Overcome Tumor Resistance to Therapy". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (19): 10689. doi:10.3390/ijms221910689. PMC 8508993. PMID 34639030.

- ^ Den Haese GJ, Walworth N, Carr AM, Gould KL (1995). "The Wee1 protein kinase regulates T14 phosphorylation of fission yeast Cdc2". Mol Biol Cell. 6 (4): 371–85. doi:10.1091/mbc.6.4.371. PMC 301198. PMID 7626804.

- ^ Kim SY, Ferrell JE (March 2007). "Substrate Competition as a Source of Ultrasensitivity in the Inactivation of Wee1". Cell. 128 (6): 1133–1145. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.039. PMID 17382882.

- ^ Coleman TR, Dunphy WG (December 1994). "Cdc2 regulatory factors". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 6 (6): 877–882. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(94)90060-4. PMID 7880537.

- ^ a b c Kellogg DR (2003). "Wee1-dependent mechanisms required for coordination of cell growth and cell division". J Cell Sci. 116 (24): 4883–90. doi:10.1242/jcs.00908. PMID 14625382.

- ^ Rowley R, Hudson J, Young PG (1992). "The wee1 protein kinase is required for radiation-induced mitotic delay". Nature. 356 (6367): 353–5. Bibcode:1992Natur.356..353R. doi:10.1038/356353a0. PMID 1549179.

- ^ Mahajan K, Fang B, Koomen JM, Mahajan NP (2012). "H2B Tyr37 phosphorylation suppresses expression of replication-dependent core histone genes". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 19 (9): 930–7. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2356. PMC 4533924. PMID 22885324.

- ^ Mahajan K, Mahajan NP (2013). "WEE1 tyrosine kinase, a novel epigenetic modifier". Trends Genet. 29 (7): 394–402. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.02.003. PMC 3700603. PMID 23537585.

- ^ Boddy MN, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P (May 1998). "Replication checkpoint enforced by kinases Cds1 and Chk1". Science. 280 (5365): 909–12. Bibcode:1998Sci...280..909B. doi:10.1126/science.280.5365.909. PMID 9572736.

- ^ Wu L, Russell P (June 1993). "Nim1 kinase promotes mitosis by inactivating Wee1 tyrosine kinase". Nature. 363 (6431): 738–41. Bibcode:1993Natur.363..738W. doi:10.1038/363738a0. PMID 8515818.

- ^ a b Coleman TR, Tang Z, Dunphy WG (March 1993). "Negative regulation of the wee1 protein kinase by direct action of the nim1/cdr1 mitotic inducer". Cell. 72 (6): 919–29. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90580-J. PMID 7681363.

- ^ Tang Z, Coleman TR, Dunphy WG (September 1993). "Two distinct mechanisms for negative regulation of the Wee1 protein kinase". EMBO J. 12 (9): 3427–36. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06017.x. PMC 413619. PMID 7504624.

- ^ Watanabe N, Broome M, Hunter T (May 1995). "Regulation of the human WEE1Hu CDK tyrosine 15-kinase during the cell cycle". EMBO J. 14 (9): 1878–91. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07180.x. PMC 398287. PMID 7743995.

- ^ Watanabe N, Arai H, Nishihara Y, et al. (March 2004). "M-phase kinases induce phospho-dependent ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFbeta-TrCP". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (13): 4419–24. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.4419W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307700101. PMC 384762. PMID 15070733.

- ^ Lee KS, Asano S, Park JE, Sakchaisri K, Erikson RL (23 October 2005). "Monitoring the Cell Cycle by Multi-Kinase-Dependent Regulation of Swe1/Wee1 in Budding Yeast". Cell Cycle. 4 (10): 1346–1349. doi:10.4161/cc.4.10.2049. PMID 16123596.

- ^ Wang F, Zhu Y, Huang Y, et al. (June 2005). "Transcriptional repression of WEE1 by Kruppel-like factor 2 is involved in DNA damage-induced apoptosis". Oncogene. 24 (24): 3875–85. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208546. PMID 15735666.

- ^ Wang Z, Li W, Li F, Xiao R (January 2024). "An update of predictive biomarkers related to WEE1 inhibition in cancer therapy". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 150 (1): 13. doi:10.1007/s00432-023-05527-y. PMC 10794259. PMID 38231277.

- ^ Do K, Doroshow JH, Kummar S (October 2013). "Wee1 kinase as a target for cancer therapy". Cell Cycle. 12 (19): 3348–3353. doi:10.4161/cc.26062. PMC 3865011. PMID 24013427.

- ^ Zhang C, Peng K, Liu Q, Huang Q, Liu T (January 2024). "Adavosertib and beyond: Biomarkers, drug combination and toxicity of WEE1 inhibitors". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 193: 104233. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104233. PMID 38103761.

- ^ https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-drug/def/adavosertib[full citation needed]

- ^ Seligmann JF, Fisher DJ, Brown LC, Adams RA, Graham J, Quirke P, Richman SD, Butler R, Domingo E, Blake A, Yates E, Braun M, Collinson F, Jones R, Brown E, de Winton E, Humphrey TC, Parmar M, Kaplan R, Wilson RH, Seymour M, Maughan TS (20 November 2021). "Inhibition of WEE1 Is Effective in TP53 - and RAS -Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Trial (FOCUS4-C) Comparing Adavosertib (AZD1775) With Active Monitoring". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 39 (33): 3705–3715. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01435. PMC 8601321. PMID 34538072.

- ^ Maldonado E, Rathmell WK, Shapiro GI, Takebe N, Rodon J, Mahalingam D, Trikalinos NA, Kalebasty AR, Parikh M, Boerner SA, Balido C, Krings G, Burns TF, Bergsland EK, Munster PN, Ashworth A, LoRusso P, Aggarwal RR (July 2024). "A Phase II Trial of the WEE1 Inhibitor Adavosertib in SETD2 - Altered Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies (NCI 10170)" (PDF). Cancer Research Communications. 4 (7): 1793–1801. doi:10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-24-0213. PMC 11264598. PMID 38920407.

- ^ Embaby A, Kutzera J, Geenen JJ, Pluim D, Hofland I, Sanders J, Lopez-Yurda M, Beijnen JH, Huitema AD, Witteveen PO, Steeghs N, van Haaften G, van Vugt MA, de Ridder J, Opdam FL (July 2023). "WEE1 inhibitor adavosertib in combination with carboplatin in advanced TP53 mutated ovarian cancer: A biomarker-enriched phase II study" (PDF). Gynecologic Oncology. 174: 239–246. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2023.05.063. PMID 37236033.

- ^ Lheureux S, Cristea MC, Bruce JP, Garg S, Cabanero M, Mantia-Smaldone G, Olawaiye AB, Ellard SL, Weberpals JI, Wahner Hendrickson AE, Fleming GF, Welch S, Dhani NC, Stockley T, Rath P, Karakasis K, Jones GN, Jenkins S, Rodriguez-Canales J, Tracy M, Tan Q, Bowering V, Udagani S, Wang L, Kunos CA, Chen E, Pugh TJ, Oza AM (January 2021). "Adavosertib plus gemcitabine for platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory recurrent ovarian cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial". The Lancet. 397 (10271): 281–292. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32554-X. PMC 10792546. PMID 33485453.

- ^ Tolcher A, Mamdani H, Chalasani P, Meric-Bernstam F, Gazdoiu M, Makris L, Pultar P, Voliotis D (July 2021). "Abstract CT016: Clinical activity of single-agent ZN-c3, an oral WEE1 inhibitor, in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial in patients with advanced solid tumors". Cancer Research. 81 (13_Supplement): CT016. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2021-CT016.

- ^ https://ir.zentalis.com/news-releases/news-release-details/zentalis-pharmaceuticals-provides-update-azenosertib-clinical[full citation needed]

- ^ Russell P, Nurse P (May 1987). "Negative regulation of mitosis by wee1+, a gene encoding a protein kinase homolog". Cell. 49 (4): 559–67. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90458-2. PMID 3032459.