War of 1812: Difference between revisions

Courcelles (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 67.211.114.82 to last revision by Redvers (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

[[Wyandot]] |

[[Wyandot]] |

||

|commander1={{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[James Madison]] <br> {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Henry Dearborn]] <br> {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Jacob Brown]] <br> {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Winfield Scott]] <br>{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Andrew Jackson]] <br>{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William Henry Harrison]] |

|commander1={{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[James Madison]] <br> {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Henry Dearborn]] <br> {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Jacob Brown]] <br> {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Winfield Scott]] <br>{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Andrew Jackson]] <br>{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William Henry Harrison]] |

||

|commander2={{Flagicon|UK}} [[Lord Liverpool]]<br>{{Flagicon|UK}} [[George Prevost]]<br>{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Isaac Brock]]{{KIA}}<br>{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Roger Sheaffe]]<br> {{Flagicon|UK}} |

|commander2={{Flagicon|UK}} [[Lord Liverpool]]<br>{{Flagicon|UK}} [[George Prevost]]<br>{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Isaac Brock]]{{KIA}}<br>{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Roger Sheaffe]]<br> {{Flagicon|UK}} ''' |

||

== Bold text == |

|||

I KNOW WHERE YOU LIVE CRISTIANA MCGREGGOR BAHAHAhahahaha i will find you'''War]]'''<br/>'''[[Spanish American War]]'''<br/>[[Spanish-American War#Pacific_Theater|Pacific Theater]]<br/>'''[[Philippine-American War]]'''<br/>[[Katipunan|Filipino Rebellion]] - [[Moro Rebellion]]<br/>'''[[Boxer Rebellion]]'''<br/>[[Battle of Peking]] - [[Battle of Tientsin]] |

|||

|strength1={{flagicon|United States|1795}} '''United States'''<br> •'''Regular Army''':<br>— 7,000 (at start of war);<br>— 35,800 (at war's end) <br> •'''Rangers''': 3,049 <br> •'''Militia''': 458,463 * <br> •'''[[United States Navy]],''' <br> '''•[[United States Marines]]''' & <br> '''•[[Revenue Cutter Service]]''' (at start of war): <br>— [[Six original United States frigates|Frigates]]: 6 <br>— Other vessels: 14 <br><br><br>'''Native allies''': 125 Choctaw, (unknown others) <ref>Upton, David. [http://web.archive.org/web/20070906061647/http://home.bak.rr.com/simpsoncounty/war1812.htm "Soldiers of the Mississippi Territory"], 2003 (HTML). Retrieved on March 27, 2009.</ref> |

|||

|strength2={{flagicon|UK}} '''British Empire'''<br> •'''British Army''':<br>— 5,200 (at start of war);<br>— 48,160 (at war's end) <br> •'''Provincial regulars''': 10,000<br> •'''Provincial Militia''': 4,000 <br> •'''[[Royal Navy]]''' & <br> '''•[[Royal Marines]]''':<br> <br>— [[Ships of the Line]]: 11 <br>— [[Frigates]]: 34<br>— Other vessels: 52 <br> •'''[[Canadian units of the War of 1812#The Provincial Marine|Provincial Marine]]''' ‡ :<br> — Ships: 9 (at start of war) <br> '''Native allies''': 10,000<ref>Robert S. Allen, ''[http://books.google.com/books?id=t9T6y_zk5B0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=his+majesty%27s+indian+allies&lr=&num=30&as_brr=0#PPA121,M1 His Majesty's Indian Allies]'', [[Dundurn Press]], 1996 (ISBN 1550021753), page 121</ref> |

|||

|casualties1= 2,260 [[killed in action]]. <br> 4,505 wounded. <br> 17,000 (est.) died from disease.<ref>All US figures from Hickey (1990) p. 302-3</ref> |

|||

|casualties2=1,600 killed in action. <br> 3,679 wounded. <br> 3,321 died from disease. |

|||

|notes= * Some militias only operated in their own regions.<br>{{KIA}} [[Killed in action]]<br> ‡ A locally raised [[coastal protection]] and seminaval force on the Great Lakes.}} |

|||

{{FixBunching|mid}} |

|||

{{campaignbox War of 1812}} |

|||

{{FixBunching|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Niagara frontier}} |

|||

{{FixBunching|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Old Northwest}} |

|||

{{FixBunching|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Chesapeake campaign}} |

|||

{{FixBunching|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: American South}} |

|||

{{FixBunching|mid}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Naval}} |

|||

{{Campaign |

|||

|name=Nineteenth century Asia/Pacific conflicts involving the United States |

|||

|raw_name=Nineteenth century Asia/Pacific conflicts involving the United States |

|||

|battles=[[Battle of Woody Point]]<br/>'''[[War of 1812]]'''<br/>'''[[First Sumatran Expedition]]'''<br/>[[First Sumatran Expedition|Battle of Quallah Battoo]]<br/>'''[[Second Sumatran Expedition]]'''<br/>[[Bombardment of Quallah Battoo]] - [[Bombardment of Muckie]]<br/>'''[[Mexican-American War]]'''<br/>[[Bear Flag Revolt|California Campaign]] - [[Battle of Mulege|Pacific Coast Campaign]]<br/>'''[[Second Opium War]]'''<br/>[[Battle of the Pearl River Forts]] - [[Battle of Taku Forts (1859)|Second Battle of Taku Forts]]<br/>'''[[American Civil War]]'''<br/>'''[[Battles for Shimonoseki|Japanese Conflict]]'''<br/>[[Battle of Shimonoseki Straits]] - [[Battles for Shimonoseki|Shimonoseki Campaign]]<br/>'''[[Formosan Expedition]]'''<br/>[[Battle of Formosa]]<br/>'''[[General Sherman Incident|Korean Conflict]]'''<br/>[[General Sherman Incident|Battle of the Keupsa Gates]] - [[Korean Expedition|Battle of Ganghwa]]<br/>'''[[Samoan Civil War|First Samoan Civil War]]'''<br/>[[Samoan crisis]]<br/>'''[[Samoan Civil War|Second Samoan Civil War]]'''<br/>'''[[Spanish American War]]'''<br/>[[Spanish-American War#Pacific_Theater|Pacific Theater]]<br/>'''[[Philippine-American War]]'''<br/>[[Katipunan|Filipino Rebellion]] - [[Moro Rebellion]]<br/>'''[[Boxer Rebellion]]'''<br/>[[Battle of Peking]] - [[Battle of Tientsin]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{FixBunching|end}} |

{{FixBunching|end}} |

||

Revision as of 17:21, 22 April 2010

| War of 1812 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars (indirect association) | |||||||

The United States Capitol after the burning of Washington. Watercolor and ink depiction from 1814, restored. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Choctaw Cherokee Creek allies |

British Empire: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Bold textSpanish American War Pacific Theater Philippine-American War Filipino Rebellion - Moro Rebellion Boxer Rebellion Battle of Peking - Battle of Tientsin | ||||||

The War of 1812 was a war fought between the United States of America and the British Empire–particularly the United Kingdom and the provinces of British North America, the antecedent of Canada. It lasted from 1812 to 1815. It was fought chiefly on the Atlantic Ocean and on the land, coasts and waterways of North America.

There were several immediate stated causes for the U.S. declaration of war. In 1807, Britain introduced a series of trade restrictions to impede ongoing American trade with France, the mortal enemy of Britain. The U.S. contested these restrictions as illegal under international law.[1] Both the impressment of American citizens into the Royal Navy, and Britain's military support of American Indians who were attacking American settlers moving into the Northwest further aggravated tensions. Indian raids hindered the expansion of U.S. into potentially valuable farmlands in the Northwest Territory, comprising the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin.[2] Some British officials–and some dissident Americans–charged that the goal was to annex part of Canada, but they did not specify which part. The states nearest Canada strongly opposed the war.[3]

Most important, the United States sought to uphold its national honor in the face of what they considered to be British insults, such as the Chesapeake affair.[4] Although the British made some concessions before the war on neutral trade, they insisted on the right to reclaim their deserting sailors. The British also had the long-standing goal of creating a large "neutral" Indian state that would cover much of Ohio, Indiana and Michigan. They made the demand as late as the fall of 1814 at the peace conference, but lost control of western Ontario at key battles on Lake Erie, thus giving the Americans control of the proposed neutral zone.[5][6]

The war was fought in four theaters. Warships and privateers of both sides attacked each other's merchant ships. The British blocked the Atlantic coast of the U.S. and mounted large-scale raids in the later stages of the war. Battles were also fought on the frontier, which ran along the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River and separated the U.S. from Upper and Lower Canada, and along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. During the war, the Americans and British invaded each other's territory. These invasions were unsuccessful or temporary. At the end of the war, the British held parts of Maine and some outposts in the sparsely populated West, while the Americans held Canadian territory near Detroit, but these occupied territories were restored at the end of the war.

In the U.S., battles such as New Orleans and the earlier successful defense of Baltimore (which inspired the lyrics of the U.S. national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner) produced a sense of euphoria over a "second war of independence" against Britain. It ushered in an "Era of Good Feelings," in which the partisan animosity that had once verged on treason practically vanished. Canada also emerged from the war with a heightened sense of national feeling and solidarity. Britain, which had regarded the war as a sideshow to the Napoleonic Wars raging in Europe, was less affected by the fighting; its government and people subsequently welcomed an era of peaceful relations and trade with the U.S.

Overview

The war was fought between the United States and the British Empire, particularly the United Kingdom and her North American colonies of Upper Canada (Ontario), Lower Canada (Québec), New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton Island (then a separate colony from Nova Scotia), and Bermuda.

On July 12, 1812, William Hull led an invading American force of 2,000 soldiers across the Detroit River and occupied the Canadian town of Sandwich (now a neighborhood of Windsor, Ontario). British Major General Isaac Brock attacked the supply lines of the occupying force with a battle group composed of British regulars, local militias, and Native Americans. By August, Hull and his troops (now numbering 2,500 with the addition of 500 Canadians) retreated to Detroit where, without a shot fired, they surrendered. The surrender cost the U.S. not only the city of Detroit, but the Michigan territory as well. Several months later the U.S. launched a second invasion of Canada, this time at the Niagara peninsula. On October 13, U.S. forces were again defeated at the Battle of Queenston Heights, where General Brock was killed. [7]

The American strategy relied in part on state-raised militias, which had the deficiencies of poor training, resisting service or being incompetently led. Financial and logistical problems also plagued the American effort. Military and civilian leadership was lacking and remained a critical American weakness until 1814. New England opposed the war and refused to provide troops or financing.[8] Britain had excellent financing and logistics, but the war with France had a higher priority, so in 1812–13, it adopted a defensive strategy. After the abdication of Napoleon in 1814, the British were able to send veteran armies to the U.S., but by then the Americans had learned how to mobilise and fight.[9]

At sea, the powerful Royal Navy blockaded much of the coastline, though it was allowing substantial exports from New England, which traded with Britain and Canada in defiance of American laws. The blockade devastated American agricultural exports, but it helped stimulate local factories that replaced goods previously imported. The American strategy of using small gunboats to defend ports was a fiasco, as the British raided the coast at will. The most famous episode was a series of British raids on the shores of Chesapeake Bay, including an attack on Washington, D.C. that resulted in the British burning of the White House, the Capitol, the Navy Yard, and other public buildings, later called the "Burning of Washington." The British power at sea was sufficient to allow the Royal Navy to levy "contributions" on bayside towns in return for not burning them to the ground. The Americans were more successful in ship-to-ship actions, and built several fast frigates in its shipyard at Sackets Harbor, New York. They sent out several hundred privateers to attack British merchant ships; British commercial interests were damaged, especially in the West Indies.[10]

The decisive use of naval power came on the Great Lakes and depended on a contest of building ships. In 1813, the Americans won control of Lake Erie and cut off British and Native American forces to the west from their supplies. Thus, the Americans gained one of their main objectives by breaking a confederation of tribes.[11] Tecumseh, the leader of the tribal confederation, was killed at the Battle of the Thames. While some Natives continued to fight alongside British troops, they subsequently did so only as individual tribes or groups of warriors, and where they were directly supplied and armed by British agents. Control of Lake Ontario changed hands several times, with neither side able or willing to take advantage of the temporary superiority. The Americans ultimately gained control of Lake Champlain, and naval victory there forced a large invading British army to turn back in 1814.

Once Britain defeated France in 1814, it ended the trade restrictions and impressment of American sailors, thus removing another cause of the war. The United Kingdom and the United States agreed to a peace that left the prewar boundaries intact.

After two years of warfare, the major causes of the war had disappeared. Neither side had a reason to continue or a chance of gaining a decisive success that would compel their opponents to cede territory or advantageous peace terms. As a result of this stalemate, the two countries signed the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814. News of the peace treaty took two months to reach the U.S., during which fighting continued. In this interim, the Americans defeated a British invasion army in the Battle of New Orleans, with American forces' sustaining 71 casualties compared with 2,000 British. The British went on to capture Fort Bowyer only to learn the next day of the war's end.

The war had the effect of uniting the populations within each country. Canadians celebrated the war as a victory because they avoided conquest. Americans celebrated victory personified in Andrew Jackson. He was the hero of the defence of New Orleans, and in 1828, was elected the 7th President of the United States.

Origins of the war

| Origins of the War of 1812 |

|---|

On June 18, the United States declared war on Britain. The war had many causes, but at the centre of the conflict was Britain's ongoing war with Napoleon’s France. The British, said Jon Latimer in 2007, had only one goal: "Britain's sole objective throughout the period was the defeat of France." If America helped France, then America had to be damaged until she stopped, or "Britain was prepared to go to any lengths to deny neutral trade with France." Latimer concludes, "All this British activity seriously angered Americans." [12]

Trade tensions

The British were engaged in war with the First French Empire and did not wish to allow the Americans to trade with France, regardless of their theoretical neutral rights to do so. As Horsman explains, "If possible, England wished to avoid war with America, but not to the extent of allowing her to hinder the British war effort against France. Moreover… a large section of influential British opinion, both in the government and in the country, thought that America presented a threat to British maritime supremacy."[13]

The American merchant marine had come close to doubling between 1802 and 1810, making it by far the largest neutral fleet. Britain was the largest trading partner, receiving 80% of all U.S. cotton and 50% of all other U.S. exports. The British public and press were resentful of the growing mercantile and commercial competition.[14] The United States' view was that Britain was in violation of a neutral nation's right to trade with others it saw fit.

Impressment

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy expanded to 175 ships of the line and 600 ships overall, requiring 140,000 sailors.[15] While the Royal Navy could man its ships with volunteers in peacetime, in war, it competed with merchant shipping and privateers for a small pool of experienced sailors and turned to impressment when it was unable to man ships with volunteers alone. A sizeable number of sailors (estimated to be as many as 11,000 in 1805) in the United States merchant navy were Royal Navy veterans or deserters who had left for better pay and conditions.[16] The Royal Navy went after them by intercepting and searching U.S. merchant ships for deserters. Such actions, especially the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, incensed the Americans.

The United States believed that British deserters had a right to become United States citizens. Britain did not recognise naturalised United States citizenship, so in addition to recovering deserters, it considered United States citizens born British liable for impressment. Exacerbating the situation was the widespread use of forged identity papers by sailors. This made it all the more difficult for the Royal Navy to distinguish Americans from non-Americans and led it to impress some Americans who had never been British. (Some gained freedom on appeal.)[17] American anger at impressment grew when British frigates stationed themselves just outside U.S. harbors in U.S. territorial waters and searched ships for contraband and impressed men in view of U.S. shores.[18] "Free trade and sailors' rights" was a rallying cry for the United States throughout the conflict.

Question of United States expansionism

American expansion into the Northwest Territory (the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin) was being obstructed by indigenous leaders like Tecumseh, supplied and encouraged by the British. Americans on the frontier demanded that interference be stopped. Before 1940, some historians held that United States expansionism into Canada was also a reason for the war. However, one subsequent historian wrote, "Almost all accounts of the 1811–1812 period have stressed the influence of a youthful band, denominated War Hawks, on Madison's policy. According to the standard picture, these men were a rather wild and exuberant group enraged by Britain's maritime practices, certain that the British were encouraging the Indians and convinced that Canada would be an easy conquest and a choice addition to the national domain. Like all stereotypes, there is some truth in this tableau; however, inaccuracies predominate. First, Perkins has shown that those favoring war were older than those opposed. Second, the lure of the Canadas has been played down by most recent investigators." [19] Some Canadian historians propounded the notion in the early 20th century, and it survives in public opinion in Ontario.[20] This view was also shared by a member of the British Parliament at the time.[21]

Madison and his advisers believed that conquest of Canada would be easy and that economic coercion would force the British to come to terms by cutting off the food supply for their West Indies colonies. Furthermore, possession of Canada would be a valuable bargaining chip. Frontiersmen demanded the seizure of Canada not because they wanted the land, but because the British were thought to be arming the Indians and thereby blocking settlement of the West.[22] As Horsman concluded, "The idea of conquering Canada had been present since at least 1807 as a means of forcing England to change her policy at sea. The conquest of Canada was primarily a means of waging war, not a reason for starting it."[23] Hickey flatly stated, "The desire to annex Canada did not bring on the war."[24] Brown (1964) concluded, "The purpose of the Canadian expedition was to serve negotiation, not to annex Canada."[25] Burt, a leading Canadian scholar, agreed completely, noting that Foster—the British minister to Washington—also rejected the argument that annexation of Canada was a war goal.[26]

The majority of the inhabitants of Upper Canada (Ontario) were either exiles from the United States (United Empire Loyalists) or postwar immigrants. The Loyalists were hostile to union with the U.S., while the other settlers seem to have been uninterested. The Canadian colonies were thinly populated and only lightly defended by the British Army. Americans then believed that many in Upper Canada would rise up and greet a United States invading army as liberators, which did not happen. One reason American forces retreated after one successful battle inside Canada was that they could not obtain supplies from the locals.[27] But the possibility of local assistance suggested an easy conquest, as former President Thomas Jefferson seemed to believe in 1812: "The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us the experience for the attack on Halifax, the next and final expulsion of England from the American continent."

The declaration of war was passed by the smallest margin recorded on a war vote in the United States Congress.[28] On May 11, Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was shot and killed by an assassin, resulting in a change of the British government, putting Lord Liverpool in power. Liverpool wanted a more practical relationship with the United States. He issued a repeal of the Orders in Council, but the U.S. was unaware of this, as it took three weeks for the news to cross the Atlantic.[28]

Course of the war

Although the outbreak of the war had been preceded by years of angry diplomatic dispute, neither side was ready for war when it came. Britain was heavily engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, most of the British Army was engaged in the Peninsular War (in Spain), and the Royal Navy was compelled to blockade most of the coast of Europe. The number of British regular troops present in Canada in July 1812 was officially stated to be 6,034, supported by Canadian militia.[29] Throughout the war, the British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies was the Earl of Bathurst. For the first two years of the war, he could spare few troops to reinforce North America and urged the commander in chief in North America (Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost) to maintain a defensive strategy. The naturally cautious Prevost followed these instructions, concentrating on defending Lower Canada at the expense of Upper Canada (which was more vulnerable to American attacks) and allowing few offensive actions. In the final year of the war, large numbers of British soldiers became available after the abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte. Prevost launched an offensive of his own into Upper New York State, but mishandled it and was forced to retreat after the British lost the Battle of Plattsburgh.

The United States was not prepared to prosecute a war, for President Madison assumed that the state militias would easily seize Canada and negotiations would follow. In 1812, the regular army consisted of fewer than 12,000 men. Congress authorised the expansion of the army to 35,000 men, but the service was voluntary and unpopular, it offered poor pay, and there were very few trained and experienced officers, at least initially. The militia called in to aid the regulars objected to serving outside their home states, were not amenable to discipline, and performed poorly in the presence of the enemy when outside of their home state. The U.S. had great difficulty financing its war. It had disbanded its national bank, and private bankers in the Northeast were opposed to the war.

The early disasters brought about chiefly by American unpreparedness and lack of leadership drove United States Secretary of War William Eustis from office. His successor, John Armstrong, Jr., attempted a coordinated strategy late in 1813 aimed at the capture of Montreal, but was thwarted by logistical difficulties, uncooperative and quarrelsome commanders and ill-trained troops. By 1814, the United States Army's morale and leadership had greatly improved, but the embarrassing Burning of Washington led to Armstrong's dismissal from office in turn. The war ended before the new Secretary of War James Monroe could put a new strategy into effect.

American prosecution of the war also suffered from its unpopularity, especially in New England, where antiwar spokesmen were vocal. The failure of New England to provide militia units or financial support was a serious blow. Threats of secession by New England states were loud; Britain immediately exploited these divisions, blockading only southern ports for much of the war and encouraging smuggling.

The war was conducted in three theatres of operations:

- The Atlantic Ocean

- The Great Lakes and the Canadian frontier

- The Southern States

Atlantic theatre

Single-ship actions

In 1812, Britain's Royal Navy was the world's largest, with over 600 cruisers in commission, plus a number of smaller vessels. Although most of these were involved in blockading the French navy and protecting British trade against (usually French) privateers, the Royal Navy nevertheless had 85 vessels in American waters.[30] By contrast, the United States Navy comprised only 8 frigates, 14 smaller sloops and brigs, and no ships of the line whatsoever. However some American frigates were exceptionally large and powerful for their class. Whereas the standard British frigate of the time was rated as a 38 gun ship, with its main battery consisting of 18-pounder guns, the USS Constitution, USS President, and USS United States were rated as 44-gun ships and were capable of carrying 56 guns, with a main battery of 24-pounders.[31]

The British strategy was to protect their own merchant shipping to and from Halifax, Canada and the West Indies, and to enforce a blockade of major American ports to restrict American trade. Because of their numerical inferiority, the Americans aimed to cause disruption through hit-and-run tactics, such as the capture of prizes and engaging Royal Navy vessels only under favorable circumstances. Days after the formal declaration of war, however, two small squadrons sailed, including the frigate USS President and the sloop USS Hornet under Commodore John Rodgers, and the frigates USS United States and USS Congress, with the brig USS Argus under Captain Stephen Decatur. These were initially concentrated as one unit under Rodgers, and it was his intention to force the Royal Navy to concentrate its own ships to prevent isolated units being captured by his powerful force. Large numbers of American merchant ships were still returning to the United States, and if the Royal Navy was concentrated, it could not watch all the ports on the American seaboard. Rodgers' strategy worked, in that the Royal Navy concentrated most of its frigates off New York Harbor under Captain Philip Broke and allowed many American ships to reach home. However, his own cruise captured only five small merchant ships, and the Americans never subsequently concentrated more than two or three ships together as a unit.

Meanwhile, the USS Constitution, commanded by Captain Isaac Hull, sailed from Chesapeake Bay on July 12. On July 17, Broke's British squadron gave chase off New York, but the Constitution evaded her pursuers after two days. After briefly calling at Boston to replenish water, on August 19, the Constitution engaged the British frigate HMS Guerriere. After a 35-minute battle, Guerriere had been dismasted and captured and was later burned. Hull returned to Boston with news of this significant victory. On October 25, the USS United States, commanded by Captain Decatur, captured the British frigate HMS Macedonian, which he then carried back to port.[32] At the close of the month, the Constitution sailed south, now under the command of Captain William Bainbridge. On December 29, off Bahia, Brazil, she met the British frigate HMS Java. After a battle lasting three hours, Java struck her colours and was burned after being judged unsalvageable. The USS Constitution, however, was undamaged in the battle and earned the name "Old Ironsides."

The successes gained by the three big American frigates forced Britain to construct five 40-gun, 24-pounder heavy frigates[33] and two of its own 50-gun "spar-decked" frigates (HMS Leander and HMS Newcastle[34]) and to razee three old 74-gun ships of the line to convert them to heavy frigates.[35] The Royal Navy acknowledged that there were factors other than greater size and heavier guns. The United States Navy's sloops and brigs had also won several victories over Royal Navy vessels of approximately equal strength. While the American ships had experienced and well-drilled volunteer crews, the enormous size of the overstretched Royal Navy meant that many ships were shorthanded and the average quality of crews suffered, and constant sea duties of those serving in North America interfered with their training and exercises.[36]

The capture of the three British frigates stimulated the British to greater exertions. More vessels were deployed on the American seaboard and the blockade tightened. On June 1, 1813, off Boston Harbor, the frigate USS Chesapeake, commanded by Captain James Lawrence, was captured by the British frigate HMS Shannon under Captain Sir Philip Broke. Lawrence was mortally wounded and famously cried out, "Don't give up the ship! Hold on, men!"[36] Although the Chesapeake was only of equal strength to the average British frigate and the crew had mustered together only hours before the battle, the British press reacted with almost hysterical relief that the run of American victories had ended.[37] It should be noted that this single victory was by ratio one of the bloodiest contests recorded during this age of sail with more dead and wounded than the HMS Victory suffered in 4 hours of combat at Trafalgar. Captain Lawrence was killed and Captain Broke would never again hold a sea command due to wounds.[38]

In January 1813, the American frigate USS Essex, under the command of Captain David Porter, sailed into the Pacific in an attempt to harass British shipping. Many British whaling ships carried letters of marque allowing them to prey on American whalers, and nearly destroyed the industry. The Essex challenged this practice. She inflicted considerable damage on British interests before she was captured off Valparaiso, Chile by the British frigate HMS Phoebe and the sloop HMS Cherub on March 28, 1814.[39]

The British 6th-rate Cruizer class brig-sloops did not fare well against the American ship-rigged sloops of war. The USS Hornet and USS Wasp constructed before the war were notably powerful vessels, and the Frolic class built during the war even more so (although USS Frolic was trapped and captured by a British frigate and a schooner). The British brig-rigged sloops tended to suffer fire to their rigging far worse than the American ship-rigged sloops, while the ship-rigged sloops could back their sails in action, giving them another advantage in manoeuvering.[40]

Following their earlier losses, the British Admiralty instituted a new policy that the three American heavy frigates should not be engaged except by a ship of the line or smaller vessels in squadron strength. An example of this was the capture of the USS President by a squadron of four British frigates in January 1815 (although the action was fought on the British side mainly by HMS Endymion).[41][42] A month later, however, the USS Constitution managed to engage and capture two smaller British warships, HMS Cyane and HMS Levant, sailing in company.

Blockade

The blockade of American ports later tightened to the extent that most American merchant ships and naval vessels were confined to port. The American frigates USS United States and USS Macedonian ended the war blockaded and hulked in New London, Connecticut. Some merchant ships were based in Europe or Asia and continued operations. Others, mainly from New England, were issued licenses to trade by Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, commander in chief on the American station in 1813. This allowed Wellington's army in Spain to receive American goods and to maintain the New Englanders' opposition to the war. The blockade nevertheless resulted in American exports decreasing from $130-million in 1807 to $7-million in 1814.[43]

The operations of American privateers (some of which belonged to the United States Navy, but most of which were private ventures) were extensive. They continued until the close of the war and were only partially affected by the strict enforcement of convoy by the Royal Navy. An example of the audacity of the American cruisers was the depredations in British home waters carried out by the American sloop USS Argus. It was eventually captured off St. David's Head in Wales by the British brig HMS Pelican on August 14, 1813. A total of 1,554 vessels were claimed captured by all American naval and privateering vessels, 1300 of which were captured by privateers.[44][45][46] However, insurer Lloyd's of London reported that only 1,175 British ships were taken, 373 of which were recaptured, for a total loss of 802.[47]

As the Royal Navy base that supervised the blockade, the Halifax profited greatly during the war. British privateers based there seized many French and American ships and sold their prizes in Halifax.

The war was the last time the British allowed privateering, since the practice was coming to be seen as politically inexpedient and of diminishing value in maintaining its naval supremacy. It was the swan song of Bermuda's privateers, who had vigorously returned to the practice after American lawsuits had put a stop to it two decades earlier. The nimble Bermuda sloops captured 298 enemy ships. British naval and privateering vessels between the Great Lakes and the West Indies captured 1,593.[48]

Atlantic coast

Preoccupied in their pursuit of American privateers when the war began, the British naval forces had some difficulty in blockading the entire U.S. coast. The British government, having need of American foodstuffs for its army in Spain, benefited from the willingness of the New Englanders to trade with them, so no blockade of New England was at first attempted. The Delaware River and Chesapeake Bay were declared in a state of blockade on December 26, 1812.

This was extended to the coast south of Narragansett by November 1813 and to the entire American coast on May 31, 1814. In the meantime, illicit trade was carried on by collusive captures arranged between American traders and British officers. American ships were fraudulently transferred to neutral flags. Eventually, the U.S. government was driven to issue orders to stop illicit trading; this put only a further strain on the commerce of the country. The overpowering strength of the British fleet enabled it to occupy the Chesapeake and to attack and destroy numerous docks and harbors.

Additionally, commanders of the blockading fleet, based at the Bermuda dockyard, were given instructions to encourage the defection of American slaves by offering freedom, as they did during the Revolutionary War. Thousands of black slaves went over to the Crown with their families and were recruited into the 3rd (Colonial) Battalion of the Royal Marines on occupied Tangier Island, in the Chesapeake. A further company of colonial marines was raised at the Bermuda dockyard, where many freed slaves—men, women, and children—had been given refuge and employment. It was kept as a defensive force in case of an attack. These former slaves fought for Britain throughout the Atlantic campaign, including the attack on Washington, D.C. and the Louisiana Campaign, and most were later re-enlisted into British West India regiments or settled in Trinidad in August 1816, where seven hundred of these ex-marines were granted land (they reportedly organised in villages along the lines of military companies). Many other freed American slaves were recruited directly into West Indian regiments or newly created British Army units. A few thousand freed slaves were later settled at Nova Scotia by the British.

Maine

Maine, then part of Massachusetts, was a base for smuggling and illegal trade between the U.S. and the British. From his base in New Brunswick, in September 1814, Sir John Coape Sherbrooke led 500 British troops in the "Penobscot Expedition". In 26 days, he raided and looted Hampden, Bangor, and Machias, destroying or capturing 17 American ships. He won the Battle of Hampden (losing two killed while the Americans lost one killed) and occupied the village of Castine for the rest of the war. The Treaty of Ghent returned this territory to the United States. The British left in April 1815, at which time they took 10,750 pounds obtained from tariff duties at Castine. This money, called the "Castine Fund", was used in the establishment of Dalhousie University, in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[49]

Chesapeake campaign and "The Star-Spangled Banner"

The strategic location of the Chesapeake Bay near America's capital made it a prime target for the British. Starting in March 1813, a squadron under Rear Admiral George Cockburn started a blockade of the bay and raided towns along the bay from Norfolk to Havre de Grace.

On July 4, 1813, Joshua Barney, a Revolutionary War naval hero, convinced the Navy Department to build the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, a squadron of twenty barges to defend the Chesapeake Bay. Launched in April 1814, the squadron was quickly cornered in the Patuxent River, and while successful in harassing the Royal Navy, they were powerless to stop the British campaign that ultimately led to the "Burning of Washington." This expedition, led by Cockburn and General Robert Ross, was carried out between August 19 and 29, 1814, as the result of the hardened British policy of 1814 (although British and American commissioners had convened peace negotiations at Ghent in June of that year). As part of this, Admiral Warren had been replaced as commander in chief by Admiral Alexander Cochrane, with reinforcements and orders to coerce the Americans into a favourable peace.

Governor-in-chief of British North America Sir George Prevost had written to the Admirals in Bermuda, calling for retaliation for the American sacking of York (now Toronto). A force of 2,500 soldiers under General Ross—aboard a Royal Navy task force composed of the HMS Royal Oak, three frigates, three sloops, and ten other vessels—had just arrived in Bermuda. Released from the Peninsular War by British victory, the British intended to use them for diversionary raids along the coasts of Maryland and Virginia. In response to Prevost's request, they decided to employ this force, together with the naval and military units already on the station, to strike at Washington, D.C.

On August 24, U.S. Secretary of War John Armstrong insisted that the British would attack Baltimore rather than Washington, even when the British army was obviously on its way to the capital. The inexperienced American militia, which had congregated at Bladensburg, Maryland, to protect the capital, was routed in the Battle of Bladensburg, opening the route to Washington. While Dolley Madison saved valuables from the Presidential Mansion, President James Madison was forced to flee to Virginia.[50]

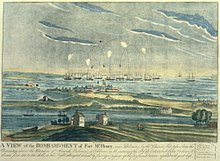

The British commanders ate the supper that had been prepared for the President before they burned the Presidential Mansion; American morale was reduced to an all-time low. The British viewed their actions as retaliation for destructive American raids into Canada, most notably the Americans' burning of York (now Toronto) in 1813. Later that same evening, a furious storm swept into Washington, D.C., sending one or more tornadoes into the city that caused more damage but finally extinguished the fires with torrential rains.[51] The naval yards were set afire at the direction of U.S. officials to prevent the capture of naval ships and supplies.[52] The British left Washington, D.C. as soon as the storm subsided. Having destroyed Washington's public buildings, including the President's Mansion and the Treasury, the British army next moved to capture Baltimore, a busy port and a key base for American privateers. The subsequent Battle of Baltimore began with the British landing at North Point, where they were met by American militia. An exchange of fire began, with casualties on both sides. General Ross was killed by an American sniper as he attempted to rally his troops. The sniper himself was killed moments later, and the British withdrew. The British also attempted to attack Baltimore by sea on September 13 but were unable to reduce Fort McHenry, at the entrance to Baltimore Harbor.

The Battle of Fort McHenry was no battle at all. British guns had range on American cannon, and stood off out of U.S. range, bombarding the fort, which returned no fire. Their plan was to coordinate with a land force, but from that distance coordination proved impossible, so the British called off the attack and left. All the lights were extinguished in Baltimore the night of the attack, and the fort was bombarded for 25 hours. The only light was given off by the exploding shells over Fort McHenry, illuminating the flag that was still flying over the fort. The defence of the fort inspired the American lawyer Francis Scott Key to write a poem that would eventually supply the lyrics to "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Great Lakes and Western Territories

Invasions of Upper and Lower Canada, 1812

American leaders assumed that Canada could be easily overrun. Former President Jefferson optimistically referred to the conquest of Canada as "a matter of marching." Many Loyalist Americans had migrated to Upper Canada after the Revolutionary War, and it was assumed they would favor the American cause, but they did not. In prewar Upper Canada, General Prevost found himself in the unusual position of purchasing many provisions for his troops from the American side. This peculiar trade persisted throughout the war in spite of an abortive attempt by the American government to curtail it. In Lower Canada, much more populous, support for Britain came from the English elite with strong loyalty to the Empire, and from the French elite, who feared American conquest would destroy the old order by introducing Protestantism and weakening the Catholic Church, Anglicization, republican democracy, and commercial capitalism. The French inhabitants feared the loss to potential American immigrants of a shrinking area of good lands.[53]

In 1812–13, British military experience prevailed over inexperienced American commanders. Geography dictated that operations would take place in the west: principally around Lake Erie, near the Niagara River between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, and near the Saint Lawrence River area and Lake Champlain. This was the focus of the three-pronged attacks by the Americans in 1812. Although cutting the St. Lawrence River through the capture of Montreal and Quebec would have made Britain's hold in North America unsustainable, the United States began operations first in the western frontier because of the general popularity there of a war with the British, who had sold arms to the American natives opposing the settlers.

The British scored an important early success when their detachment at St. Joseph Island, on Lake Huron, learned of the declaration of war before the nearby American garrison at the important trading post at Mackinac Island, in Michigan. A scratch force landed on the island on July 17, 1812, and mounted a gun overlooking Fort Mackinac. After the British fired one shot from their gun, the Americans, taken by surprise, surrendered. This early victory encouraged the natives, and large numbers of them moved to help the British at Amherstburg.

An American army under the command of William Hull invaded Canada on July 12, with his forces chiefly composed of militiamen.[54] Once on Canadian soil, Hull issued a proclamation ordering all British subjects to surrender, or "the horrors, and calamities of war will stalk before you." He also threatened to kill any British prisoner caught fighting alongside a native. The proclamation helped stiffen resistance to the American attacks. The senior British officer in Upper Canada, Major General Isaac Brock, decided to oppose Hull's forces, and felt that he should make a bold action to calm the settler population in Canada, and to try and convince the aboriginals that were needed to defend the region that Britain was strong.[54] Hull was worried that his army was too weak to achieve its objectives, and engaged in minor skirmishing and felt more vulnerable after the British captured a vessel on Lake Erie carrying his baggage, medical supplies, and important papers.[54] On July 17, without a fight, the American fort on Mackinac Island surrendered after a group of soldiers, fur traders, and native warriors ordered by Brock to capture the settlement deployed a piece of artillery overlooking the post before the fort realised it, which led to its capitulation.[54] This capture secured British fur trade operations in the area and maintained a British connection to the Native American tribes in the Mississippi region, as well as inspiring a sizeable number of Natives of the upper lakes region to combat the United States.[54] Hull, believing after he learned about the capture that the tribes along the Detroit border would rise up and oppose him and perhaps attack Americans on the frontier, on August 8 withdrew most of his army from Canada back to secure Detroit whilst sending a request for reinforcements and ordering the American garrison at Fort Dearborn to abandon the post for fear of an aboriginal attack.[54]

Brock advanced on Fort Detroit with 1,200 men. Brock sent a fake correspondence and allowed the letter to be captured by the Americans, saying they required only 5,000 Native warriors to capture Detroit. Hull feared the natives and their threats of torture and scalping. Believing the British had more troops than they did, Hull surrendered at Detroit without a fight on August 16. Fearing British-instigated indigenous attacks on other locations, Hull ordered the evacuation of the inhabitants of Fort Dearborn (Chicago) to Fort Wayne. After initially being granted safe passage, the inhabitants (soldiers and civilians) were attacked by Potowatomis on August 15 after traveling two miles (3 km) in what is known as the Battle of Fort Dearborn. The fort was subsequently burned.

Brock promptly transferred himself to the eastern end of Lake Erie, where American General Stephen Van Rensselaer was attempting a second invasion. An armistice (arranged by Prevost in the hope the British renunciation of the Orders in Council to which the United States objected might lead to peace) prevented Brock from invading American territory. When the armistice ended, the Americans attempted an attack across the Niagara River on October 13, but suffered a crushing defeat at Queenston Heights. Brock was killed during the battle. While the professionalism of the American forces would improve by the war's end, British leadership suffered after Brock's death. A final attempt in 1812 by American General Henry Dearborn to advance north from Lake Champlain failed when his militia refused to advance beyond American territory.

In contrast to the American militia, the Canadian militia performed well. French Canadians, who found the anti-Catholic stance of most of the United States troublesome, and United Empire Loyalists, who had fought for the Crown during the American Revolutionary War, strongly opposed the American invasion. However, many in Upper Canada were recent settlers from the United States who had no obvious loyalties to the Crown. Nevertheless, while there were some who sympathised with the invaders, the American forces found strong opposition from men loyal to the Empire.[55]

American Northwest, 1813

After Hull's surrender of Detroit, General William Henry Harrison was given command of the U.S. Army of the Northwest. He set out to retake the city, which was now defended by Colonel Henry Procter in conjunction with Tecumseh. A detachment of Harrison's army was defeated at Frenchtown along the River Raisin on January 22, 1813. Procter left the prisoners with an inadequate guard, who could not prevent some of his North American aboriginal allies from attacking and killing perhaps as many as sixty Americans, many of whom were Kentucky militiamen.[56] The incident became known as the "River Raisin Massacre." The defeat ended Harrison's campaign against Detroit, and the phrase "Remember the River Raisin!" became a rallying cry for the Americans.

In May 1813, Procter and Tecumseh set siege to Fort Meigs in northern Ohio. American reinforcements arriving during the siege were defeated by the natives, but the fort held out. The Indians eventually began to disperse, forcing Procter and Tecumseh to return to Canada. A second offensive against Fort Meigs also failed in July. In an attempt to improve Indian morale, Procter and Tecumseh attempted to storm Fort Stephenson, a small American post on the Sandusky River, only to be repulsed with serious losses, marking the end of the Ohio campaign.

On Lake Erie, American commander Captain Oliver Hazard Perry fought the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813. His decisive victory ensured American control of the lake, improved American morale after a series of defeats, and compelled the British to fall back from Detroit. This paved the way for General Harrison to launch another invasion of Upper Canada, which culminated in the U.S. victory at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813, in which Tecumseh was killed. Tecumseh's death effectively ended the North American indigenous alliance with the British in the Detroit region. American control of Lake Erie meant the British could no longer provide essential military supplies to their aboriginal allies, who therefore dropped out of the war. The Americans controlled the area during the war.

Niagara frontier, 1813

Because of the difficulties of land communications, control of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River corridor was crucial. When the war began, the British already had a small squadron of warships on Lake Ontario and had the initial advantage. To redress the situation, the Americans established a Navy yard at Sackett's Harbor, New York. Commodore Isaac Chauncey took charge of the large number of sailors and shipwrights sent there from New York; they completed the second warship built there in a mere 45 days. Ultimately, 3000 men worked at the shipyard, building eleven warships and many smaller boats and transports. Having regained the advantage by their rapid building program, Chauncey and Dearborn attacked York (now called Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada, on April 27, 1813. The Battle of York was an American victory, marred by looting and the burning of the Parliament buildings and a library. However, Kingston was strategically more valuable to British supply and communications along the St. Lawrence. Without control of Kingston, the U.S. navy could not effectively control Lake Ontario or sever the British supply line from Lower Canada.

On May 27, 1813, an American amphibious force from Lake Ontario assaulted Fort George on the northern end of the Niagara River and captured it without serious losses. The retreating British forces were not pursued, however, until they had largely escaped and organised a counteroffensive against the advancing Americans at the Battle of Stoney Creek on June 5. On June 24, with the help of advance warning by Loyalist Laura Secord, another American force was forced to surrender by a much smaller British and native force at the Battle of Beaver Dams, marking the end of the American offensive into Upper Canada. Meanwhile, Commodore James Lucas Yeo had taken charge of the British ships on the lake and mounted a counterattack, which was nevertheless repulsed at the Battle of Sackett's Harbor. Thereafter, Chauncey and Yeo's squadrons fought two indecisive actions, neither commander seeking a fight to the finish.

Late in 1813, the Americans abandoned the Canadian territory they occupied around Fort George. They set fire to the village of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) on December 15, 1813, incensing the British and Canadians. Many of the inhabitants were left without shelter, freezing to death in the snow. This led to British retaliation following the Capture of Fort Niagara on December 18, 1813, and similar destruction at Buffalo on December 30, 1813.

In 1814, the contest for Lake Ontario turned into a building race. Eventually, by the end of the year, Yeo had constructed the HMS St. Lawrence, a first-rate ship of the line of 112 guns that gave him superiority, but the Engagements on Lake Ontario were an indecisive draw.

St. Lawrence and Lower Canada, 1813

The British were potentially most vulnerable over the stretch of the St. Lawrence where it formed the frontier between Upper Canada and the United States. During the early days of the war, there was illicit commerce across the river. Over the winter of 1812 and 1813, the Americans launched a series of raids from Ogdensburg on the American side of the river, which hampered British supply traffic up the river. On February 21, Sir George Prevost passed through Prescott on the opposite bank of the river with reinforcements for Upper Canada. When he left the next day, the reinforcements and local militia attacked. At the Battle of Ogdensburg, the Americans were forced to retire.

For the rest of the year, Ogdensburg had no American garrison, and many residents of Ogdensburg resumed visits and trade with Prescott. This British victory removed the last American regular troops from the Upper St. Lawrence frontier and helped secure British communications with Montreal. Late in 1813, after much argument, the Americans made two thrusts against Montreal. The plan eventually agreed upon was for Major General Wade Hampton to march north from Lake Champlain and join a force under General James Wilkinson that would embark in boats and sail from Sackett's Harbor on Lake Ontario and descend the St. Lawrence. Hampton was delayed by bad roads and supply problems and also had an intense dislike of Wilkinson, which limited his desire to support his plan. On October 25, his 4,000-strong force was defeated at the Chateauguay River by Charles de Salaberry's smaller force of French-Canadian Voltigeurs and Mohawks. Wilkinson's force of 8,000 set out on October 17, but was also delayed by bad weather. After learning that Hampton had been checked, Wilkinson heard that a British force under Captain William Mulcaster and Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Wanton Morrison was pursuing him, and by November 10, he was forced to land near Morrisburg, about 150 kilometers (90 mi.) from Montreal. On November 11, Wilkinson's rear guard, numbering 2,500, attacked Morrison's force of 800 at Crysler's Farm and was repulsed with heavy losses. After learning that Hampton could not renew his advance, Wilkinson retreated to the U.S. and settled into winter quarters. He resigned his command after a failed attack on a British outpost at Lacolle Mills.

Niagara and Plattsburgh Campaigns, 1814

By the middle of 1814, American generals, including Major Generals Jacob Brown and Winfield Scott, had drastically improved the fighting abilities and discipline of the army. Their renewed attack on the Niagara peninsula quickly captured Fort Erie. Winfield Scott then gained a victory over an inferior British force at the Battle of Chippawa on July 5. An attempt to advance further ended with a hard-fought but inconclusive battle at Lundy's Lane on July 25.

The outnumbered Americans withdrew but withstood a prolonged Siege of Fort Erie. The British suffered heavy casualties in a failed assault and were weakened by exposure and shortage of supplies in their siege lines. Eventually the British raised the siege, but American Major General George Izard took over command on the Niagara front and followed up only halfheartedly. The Americans lacked provisions, and eventually destroyed the fort and retreated across the Niagara.

Meanwhile, following the abdication of Napoleon, 15,000 British troops were sent to North America under four of Wellington’s ablest brigade commanders. Fewer than half were veterans of the Peninsula and the rest came from garrisons. Along with the troops came instructions for offensives against the United States. British strategy was changing, and like the Americans, the British were seeking advantages for the peace negotiations. Governor-General Sir George Prevost was instructed to launch an invasion into the New York–Vermont region. The army available to him outnumbered the American defenders of Plattsburgh, but control of this town depended on being able to control Lake Champlain. On the lake, the British squadron under Captain George Downie and the Americans under Master Commandant Thomas MacDonough were more evenly matched.

On reaching Plattsburgh, Prevost delayed the assault until the arrival of Downie in the hastily completed 36-gun frigate HMS Confiance. Prevost forced Downie into a premature attack, but then unaccountably failed to provide the promised military backing. Downie was killed and his naval force defeated at the naval Battle of Plattsburgh in Plattsburgh Bay on September 11, 1814. The Americans now had control of Lake Champlain; Theodore Roosevelt later termed it "the greatest naval battle of the war." The successful land defence was led by Alexander Macomb. To the astonishment of his senior officers, Prevost then turned back, saying it would be too hazardous to remain on enemy territory after the loss of naval supremacy. Prevost's political and military enemies forced his recall. In London, a naval court-martial of the surviving officers of the Plattsburgh Bay debacle decided that defeat had been caused principally by Prevost’s urging the squadron into premature action and then failing to afford the promised support from the land forces. Prevost died suddenly, just before his own court-martial was to convene. Prevost's reputation sank to a new low, as Canadians claimed that their militia under Brock did the job and he failed. Recently, however, historians have been more kindly, measuring him not against Wellington but against his American foes. They judge Prevost’s preparations for defending the Canadas with limited means to be energetic, well-conceived, and comprehensive; and against the odds, he had achieved the primary objective of preventing an American conquest.[53]

American West, 1813–14

Far to the west of where regular British forces were fighting, more than 65 forts were built in the Illinois Territory, mostly by American settlers. Skirmishes between settlers and U.S. soldiers against natives allied to the British occurred throughout the Mississippi River valley during the war. The Sauk were considered the most formidable tribe.

At the beginning of the war, Fort Osage, the westernmost U.S. outpost along the Missouri River, was abandoned.[57] In September 1813, Fort Madison, an American outpost in what is now Iowa, was abandoned after it was attacked and besieged by natives, who had support from the British. This was one of the few battles fought west of the Mississippi. Black Hawk participated in the siege of Fort Madison, which helped to form his reputation as a resourceful Sauk leader.[58][59][60]

Little of note took place on Lake Huron in 1813, but the American victory on Lake Erie and the recapture of Detroit isolated the British there. During the ensuing winter, a Canadian party under Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall established a new supply line from York to Nottawasaga Bay on Georgian Bay. When he arrived at Fort Mackinac with supplies and reinforcements, he sent an expedition to recapture the trading post of Prairie du Chien in the far west. The Siege of Prairie du Chien ended in a British victory on July 20, 1814.

Earlier in July, the Americans sent a force of five vessels from Detroit to recapture Mackinac. A mixed force of regulars and volunteers from the militia landed on the island on August 4. They did not attempt to achieve surprise, and at the brief Battle of Mackinac Island, they were ambushed by natives and forced to re-embark. The Americans discovered the new base at Nottawasaga Bay, and on August 13, they destroyed its fortifications and a schooner that they found there. They then returned to Detroit, leaving two gunboats to blockade Mackinac. On September 4, these gunboats were taken unawares and captured by enemy boarding parties from canoes and small boats. This Engagement on Lake Huron left Mackinac under British control.

The British garrison at Prairie du Chien also fought off another attack by Major Zachary Taylor. In this distant theatre, the British retained the upper hand until the end of the war, through the allegiance of several indigenous tribes that received British gifts and arms. In 1814 U.S. troops retreating from the Battle of Credit Island on the upper Mississippi attempted to make a stand at Fort Johnson, but the fort was soon abandoned, along with most of the upper Mississippi valley.[61]

After the U.S. was pushed out of the Upper Mississippi region, they held on to eastern Missouri and the St. Louis area. Two notable battles fought against the Sauk were the Battle of Cote Sans Dessein, in April 1815, at the mouth of the Osage River in the Missouri Territory, and the Battle of the Sink Hole, in May 1815, near Fort Cap au Gris.[62]

At the conclusion of peace, Mackinac and other captured territory was returned to the United States. Fighting between Americans, the Sauk, and other indigenous tribes continued through 1817, well after the war ended in the east.[63]

Creek War

In March 1814, Jackson led a force of Tennessee militia, Choctaw,[64] Cherokee warriors, and U.S. regulars southward to attack the Creek tribes, led by Chief Menawa. On March 26, Jackson and General John Coffee decisively defeated the Creek at Horseshoe Bend, killing 800 of 1,000 Creeks at a cost of 49 killed and 154 wounded out of approximately 2,000 American and Cherokee forces. Jackson pursued the surviving Creek until they surrendered. Most historians consider the Creek War as part of the War of 1812, because the British supported them.

Southern theatre

James Wilkinson captured Mobile, Alabama from the Spanish in March 1813. It later became the sole permanent territorial gain for the United States.

The Treaty of Ghent

Factors leading to the peace negotiations

By 1814, both sides, weary of a costly war that seemingly offered nothing but stalemate, were ready to grope their way to a settlement and sent delegates to Ghent, Belgium. The negotiations began in early August and dragged on until Dec. 24, when a final agreement was signed; both sides had to ratify it before it could take effect. Meanwhile both sides planned new invasions.

It is difficult to measure accurately the costs of the American war to Britain, because they are bound up in general expenditure on the Napoleonic War in Europe. But an estimate may be made based on the increased borrowing undertaken during the period, with the American war as a whole adding some £25 million to the national debt.[65] In the U.S., the cost was $105 million, although because the British pound was worth considerably more than the dollar, the costs of the war to both sides were roughly equal.[66] The national debt rose from $45 million in 1812 to $127 million by the end of 1815, although by selling bonds and treasury notes at deep discounts—and often for irredeemable paper money due to the suspension of specie payment in 1814—the government received only $34 million worth of specie.[67] By this time, the British blockade of U.S. ports was having a detrimental effect on the American economy. Licensed flour exports, which had been close to a million barrels in 1812 and 1813, fell to 5,000 in 1814. By this time, insurance rates on Boston shipping had reached 75%, coastal shipping was at a complete standstill, and New England was considering secession.[68] Exports and imports fell dramatically as American shipping engaged in foreign trade dropped from 948,000 tons in 1811 to just 60,000 tons by 1814. But although American privateers found chances of success much reduced, with most British merchantmen now sailing in convoy, privateering continued to prove troublesome to the British. With insurance rates between Liverpool, England and Halifax, Nova Scotia rising to 30%, the Morning Chronicle complained that with American privateers operating around the British Isles, "We have been insulted with impunity."[69] The British could not fully celebrate a great victory in Europe until there was peace in North America, and more pertinently, taxes could not come down until such time. Landowners particularly balked at continued high taxation; both they and the shipping interests urged the government to secure peace.[70]

Negotiations and peace

Britain, which had forces in uninhabited areas near Lake Superior and Lake Michigan and two towns in Maine, demanded the ceding of large areas, plus turning most of the Midwest into a neutral zone for Indians. American public opinion was outraged when Madison published the demands; even the Federalists were now willing to fight on. The British were planning three invasions. One force burned Washington but failed to capture Baltimore, and sailed away when its commander was killed. In New York, 10,000 British veterans were marching south until a decisive defeat at the Battle of Plattsburgh forced them back to Canada.[71] Nothing was known of the fate of the third large invasion force aimed at capturing New Orleans and southwest. The Prime Minister wanted the Duke of Wellington to command in Canada and finally win the war; Wellington said no, because the war was a military stalemate and should be promptly ended:

I think you have no right, from the state of war, to demand any concession of territory from America ... You have not been able to carry it into the enemy's territory, notwithstanding your military success and now undoubted military superiority, and have not even cleared your own territory on the point of attack. You can not on any principle of equality in negotiation claim a cessation of territory except in exchange for other advantages which you have in your power ... Then if this reasoning be true, why stipulate for the uti possidetis? You can get no territory: indeed, the state of your military operations, however creditable, does not entitle you to demand any.[72]

With a rift opening between Britain and Russia at the Congress of Vienna and little chance of improving the military situation in North America, Britain was prepared to end the war promptly. In concluding the war, the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, was taking into account domestic opposition to continued taxation, especially among Liverpool and Bristol merchants—keen to get back to doing business with America—and there was nothing to gain from prolonged warfare.[73]

On December 24, 1814, diplomats from the two countries, meeting in Ghent, United Kingdom of the Netherlands (now in Belgium), signed the Treaty of Ghent. This was ratified by the Americans on February 16, 1815. The British government approved the treaty within a few hours of receiving it and the Prince Regent signed it on December 27, 1814.

Aftermath

The Battle of New Orleans and other post-treaty fighting

Unaware of the peace, Andrew Jackson's forces moved to New Orleans, Louisiana in late 1814 to defend against a large-scale British invasion. Jackson defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. At the end of the day, the British had a little over 2,000 casualties: 278 dead (including three senior generals Pakenham, Gibbs, and Major General Keane), 1186 wounded, and 484 captured or missing.[74] The Americans had 71 casualties: 13 dead, 39 wounded, and 19 missing. It was hailed as a great victory for the U.S., making Jackson a national hero and eventually propelling him to the presidency.[75][76]

The British gave up on New Orleans but moved to attack the Gulf Coast port of Mobile, Alabama, which the Americans had seized from the Spanish in 1813. In one of the last military actions of the war, 1,000 British troops won the Battle of Fort Bowyer on February 12, 1815. When news of peace arrived the next day, they abandoned the fort and sailed home. In May 1815, a band of British-allied Sauk, unaware that the war had ended months ago, attacked a small band of U.S. soldiers northwest of St. Louis.[77] Intermittent fighting, primarily with the Sauk, continued in the Missouri Territory well into 1817, although it is unknown if the Sauk were acting on their own or on behalf of the United Kingdom.[78] Several uncontacted isolated warships continued fighting well into 1815 and were the last American forces to take offensive action against the British.

Losses and compensation

British losses in the war were about 1,600 killed in action and 3,679 wounded; 3,321 British died from disease. American losses were 2,260 killed in action and 4,505 wounded. While the number of Americans who died from disease is not known, it is estimated that 17,000 perished.[79] These figures do not include deaths among American or Canadian militia forces or losses among native tribes.

In addition, at least 3,000 American slaves escaped to the British because of their offer of freedom, the same as they had made in the American Revolution. Many other slaves simply escaped in the chaos of war and achieved their freedom on their own. The British settled some of the newly freed slaves in Nova Scotia.[80] Four hundred freedmen were settled in New Brunswick.[81] The Americans protested that Britain's failure to return the slaves violated the Treaty of Ghent. After arbitration by the Czar of Russia the British paid $1,204,960, in damages to Washington, which reimbursed the slaveowners.[82]

Terms of the Treaty of Ghent

The war was ended by the Treaty of Ghent, signed on December 24, 1814 and taking effect February 18, 1815. The terms stated that fighting between the United States and Britain would cease, all conquered territory was to be returned to the prewar claimant, the Americans were to gain fishing rights in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, and that the United States and Britain agreed to recognise the prewar boundary between Canada and the United States.

The Treaty of Ghent, which was promptly ratified by the Senate in 1815, ignored the grievances that led to war. American complaints of Indian raids, impressment and blockades had ended when Britain's war with France (apparently) ended, and were not mentioned in the treaty. The treaty proved to be merely an expedient to end the fighting. Mobile and parts of western Florida remained permanently in American possession, despite objections by Spain.[83] Thus, the war ended with no significant territorial losses for either side.

Who won the War?

During the 19th century the popular image of the war in the United States was of an American victory, and in Canada, of a Canadian victory. Each young country saw her self-perceived victory as an important foundation of her growing nationhood. The British, on the other hand, who had been preoccupied by Napoleon's challenge in Europe, paid little attention to what was to them a peripheral and secondary dispute. By the 21st century it was a forgotten war in the U.S., Britain and Quebec, although still remembered in the rest of Canada, especially Ontario. [In a late-2009 poll, 37% of Canadians said the war was a Canadian victory, 9% said the U.S. won, 15% called it a draw, and 39%—mainly younger Canadians—said they knew too little to comment.] [84]

Historians have differing and more complex interpretations. They are in full agreement that the native Indians were the war's clear losers, losing land, power and any hope of keeping their semi-autonomous status. Historians also agree that ending the war with neither side gaining or losing territory allowed for the peaceful settlement of boundary disputes and for the opening of a permanent era of good will and friendly relations between the U.S. and Canada.

In recent decades the view of the majority of American historians has been that the war ended in stalemate, with the Treaty of Ghent closing a war that had become militarily inconclusive. Neither side wanted to continue fighting since the main causes had disappeared and since there were no large lost territories for one side or the other to reclaim by force. Insofar as they see the war's untriumphant resolution as allowing two centuries of peaceful and mutually-beneficial intercourse between the U.S., Britain and Canada, these historians often conclude that all three nations were the "real winners" of the War of 1812. These writers often add that the war could have been avoided in the first place by better diplomacy. It is seen as a mistake for everyone concerned because it was badly planned and marked by multiple fiascoes and failures on both sides, as shown especially by the repeated American failure to seize parts of Canada, and the failed British invasions of New Orleans and upstate New York.[85]

However, other scholars hold that the war constituted a British victory and an American defeat. They argue that the British achieved their military objectives in 1812 (by stopping the repeated American invasions of Canada) and that Canada retained her independence of the United States. By contrast, they say, the Americans suffered a defeat when their armies failed to achieve their war goal of seizing part or all of Canada. Additionally, they argue the US lost as it failed to stop impressment, which the British refused to repeal, and the US actions had no effect on the orders in council, which were rescinded before the war started.[86]

A second minority view is that both the US and Britain won the war–that is, both achieved their main objectives, while the Indians were the losing party.[87] [88]. The British won by losing no territories and achieving their great war goal, the total defeat of Napoleon. U.S. won by (1) securing her honour and successfully resisting a powerful empire once again, thus winning a "second war of independence" and securing a "separate and equal station" "among the powers of the earth",[89] (2) ending the threat of Indian raids and the British plan for a semi-independent Indian sanctuary—thereby opening an unimpeded path for the United States' westward expansion—and (3) stopping the Royal Navy from restricting American trade and impressing American sailors.[90]

Consequences

Neither side lost territory in the war[91], nor did the treaty that ended it address the original points of contention—and yet it changed much between the United States of America and Britain.

The Treaty of Ghent established the status quo ante bellum; that is, there were no territorial changes made by either side. The issue of impressment was made moot when the Royal Navy stopped impressment after the defeat of Napoleon. Except for occasional border disputes and the circumstances of the American Civil War, relations between the U.S. and Britain remained generally peaceful for the rest of the 19th century, and the two countries became close allies in the 20th century.

Border adjustments between the U.S. and British North America were made in the Treaty of 1818. A border dispute along the Maine-New Brunswick border was settled by the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty after the bloodless Aroostook War, and the border in the Oregon Territory was settled by splitting the disputed area in half by the 1846 Oregon Treaty. Yet, according to Winston Churchill, "The lessons of the war were taken to heart. Anti-American sentiment in Britain ran high for several years, but the United States was never again refused proper treatment as an independent power."[92]

United States

The U.S. suppressed the native American resistance on its western and southern borders. The nation also gained a psychological sense of complete independence as people celebrated their "second war of independence."[22] Nationalism soared after the victory at the Battle of New Orleans. The opposition Federalist Party collapsed, and the Era of Good Feelings ensued. The U.S. did make one minor territorial gain during the war, though not at Britain's expense, when it captured Mobile, Alabama from Spain.[93]

No longer questioning the need for a strong Navy, the U.S. built three new 74-gun ships of the line and two new 44-gun frigates shortly after the end of the war.[94] (Another frigate had been destroyed to prevent it being captured on the stocks.)[95] In 1816, the U.S. Congress passed into law an "Act for the gradual increase of the Navy" at a cost of $1,000,000 a year for eight years, authorizing 9 ships of the line and 12 heavy frigates.[96] The Captains and Commodores of the U.S. Navy became the heroes of their generation in the U.S. Decorated plates and pitchers of Decatur, Hull, Bainbridge, Lawrence, Perry, and Macdonough were made in Staffordshire, England, and found a ready market in the United States. Three of the war heroes used their celebrity to win national office: Andrew Jackson (elected President in 1828 and 1832), Richard Mentor Johnson (elected Vice President in 1836), and William Henry Harrison (elected President in 1840).

New England states became increasingly frustrated over how the war was being conducted and how the conflict was affecting them. They complained that the U.S. government was not investing enough in the states' defences militarily and financially, and that the states should have more control over their militia. The increased taxes, the British blockade, and the occupation of some of New England by enemy forces also agitated public opinion in the states.[97] As a result, at the Hartford Convention (December 1814–January 1815) held in Connecticut, New England representatives asked New England to have its states' powers fully restored. Nevertheless, a common misconception propagated by newspapers of the time was that the New England representatives wanted to secede from the Union and make a separate peace with the British. This view is not supported by what happened at the Convention.[98]