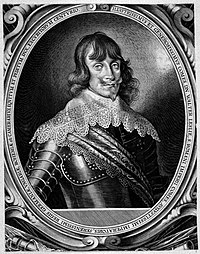

Walter Leslie (field marshal)

Count Walter Leslie (Fetternear House, Aberdeenshire, 1607 – Vienna, 4 March 1667) was a Scottish soldier and diplomat. He gained the positions of Imperial Field Marshal, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, Governor on the Croatian-Slavonian Military Frontier, Imperial Ambassador to Naples, Rome in 1645 and to Constantinople in 1665–1666.

Family

[edit]Walter Leslie was born to a prominent Scottish noble family from the Clan Leslie. His father John was the 10th Baron of Balquhain and his mother Joan was a daughter of Alexander Baron of Gogar. In 1647, he married Anna Francesca von Dietrichstein, daughter of Count Maximilian von Dietrichstein. They had no children. He was succeeded by his nephew, Count James Leslie, who continued the Leslie line at the family castle, Nové Město nad Metují.

Early military career: 1624–1632

[edit]In 1624, Walter Leslie crossed the North Sea to fight with the Protestant Army of the United Provinces. By 1628, he was in Stralsund in Northern Germany fighting for either the Danes or the Swedes. In 1630, he transferred to the army of the (Catholic) Holy Roman Emperor and fought alongside his countryman John Gordon that summer in War of the Mantuan Succession in Northern Italy. During 1631, the army was recalled from Italy. In December 1631 Leslie arrived in Northern Germany to fight under General Albrecht von Wallenstein against the Swedes.[1]

By July 1632, Leslie had risen to the rank of oberwachtmeister, or sergeant in the infantry ranks of Count Adam Erdmann Trčka, Wallenstein's brother-in-law, and was still under John Gordon, then lieutenant colonel. The military relationship between Leslie and Gordon would become increasingly important as they became closer to Wallenstein. Leslie fought under Gordon at Bentheim in lower Saxony and at Freistadt in upper Austria. Both men were captured at Freistadt by the Swedes after having had joint command of 1000 Scottish and Irish musketeers. After that, Gordon rose to commander of a regiment and Leslie became his spokesman in court. This was the first time Leslie was put in such a position, although it would not be the last. In November 1632 Leslie fought with Gordon at the Battle of Lützen. That was a Protestant victory, but cost the life of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. After that, they were garrisoned at Eger and Leslie was again commissioned as Gordon's second in command.[2]

Plot to assassinate Wallenstein: 1633–1634

[edit]In December 1633 Italian Imperial generals began to plot ways to remove Wallenstein from power. During that time, Leslie, Gordon and Irish Colonel Walter Butler remained in the service of Wallenstein but began to correspond with the Italian generals.[3] Leslie wrote to one, calling him the "protector of all foreign cavaleirs," pledged his allegiance to the Ferdinand II and requested a promotion based on his service to the emperor.[4] As historian David Worthington points out, the letter was timed to arrive on 12 January, the day before the Pilsen Agreement was signed by 47 of Wallenstein's officers to remain loyal to him. Leslie never signed the agreement. Days later, the Italian generals and 18 other senior officers signed the Pilsen Reverse, a document which expressed their loss of faith in Wallenstein's loyalty and ability.[5] In January 1633 Ferdinand II granted immunity to all signers of the Pilsen Agreement except the top generals. By this time, Leslie and Gordon had both aligned themselves with one of the Italian generals[who?] who had just been made a field marshal and had been preparing their musketeers in Eger.[6] In January 1634 Ferdinand issued a secret arrest warrant for Wallenstein. The general began exploring the allegiances of his Scottish officers, Gordon and Leslie by offering Gordon a promotion and asking to meet with Leslie.[7]

As Butler escorted Wallenstein into Eger, Leslie and Gordon were inside the castle walls awaiting their arrival. There are several accounts of what followed in the late days of February, but some events and details are unanimous. On 24 February Wallenstein entered Eger and retired to his bed at the Burgomaster's house, outside the castle walls. That night, Leslie dined with Butler and Gordon and they finalized their plans to assassinate Wallenstein and his senior officers.[8] After dinner, a messenger came for Wallenstein and Leslie took him to the general's quarters. The letter was from Ferdinand II and it officially dismissed him as a general and indicted him as a traitor. Wallenstein is then reported to have let out his frustrations to Leslie and even confided in Leslie his plans to join forces with Saxe-Weimar.[9]

The next morning, Leslie, Butler and Gordon all took an oath with one of the loyalist officers, Ilow, to remain loyal to Wallenstein. Later that day, the Scotsmen invited all of the loyalist officers to a banquet to celebrate Wallenstein. Adam Trčka, Vilem Kinsky, Christian von Ilow and a lower ranking officer, Niemann all attended, but Wallenstein declined due to illness. At the banquet they drank heavily, made toasts to the General, cursed the court in Vienna and had dessert. Again, reports of events differ slightly in the small details but what is agreed is that at the end of dinner, Leslie, Butler and Gordon all stood up, drew their swords and yelled something along the lines of "Long live Ferdinand and the House of Austria!" At that point, the drawbridge had been raised and the Irish dragoons had been let into the banquet hall. Although Leslie was wounded in the slaughter, all of Wallenstein's officers were killed. Next, Leslie left the walls to gather Walter Devereux and a team to go to Wallenstein's quarters, where he was asleep, and kill him, and so they did.[10][11]

Leslie was the first to bring word to Vienna and therefore the Emperor heard his name first. Leslie and his fellows were rewarded handsomely by Ferdinand II for their efforts. Leslie was given Trčka's castle, Nové Město nad Metují and some other properties as well as the "die golden ketten" or the imperial golden chain. Leslie's career as a military officer, politician, diplomat, and imperial noble skyrocketed as a result of assassinating Wallenstein.[12]

Imperial court, new titles, and diplomacy: 1634–1650

[edit]

Leslie was made an imperial chamberlain by Ferdinand II in 1634. His military rank was increased to a lieutenant field marshal and head of the bodyguard for the King of Hungary, and he was given command of two regiments. Just after his promotions, in the summer of 1634 he took part in the successful siege on Regensburg. In September 1634 he fought at the imperial victory at the Battle of Nordlingen. In the months leading up to the Peace of Prague, Leslie was in Rathenow in Brandenburg. Historian David Worthington claims that of all the assassins of Wallenstein, Leslie was rewarded the most and ultimately his career grew the most out of that event.[13]

In September 1636, Leslie and the imperialists were defeated by the Swedes at the Battle of Wittstock. In 1637, Leslie wrote to the dying Ferdinand II, making his argument that he had Habsburg blood dating back over half of a century. After Ferdinand II's death, Ferdinand III approved the request and ennobled Leslie as an Imperial Count.[14] This new title brought with it a new lifestyle, new political respect and more diplomatic opportunities. Leslie served as a Stuart-Habsburg intermediary at the Ratisbon Electoral meeting (1636–43), Imperial envoy to the Spanish Netherlands (1639), diplomatic trips to the Caroline Court in Spain, delegate in Regensburg (1640), and ambassador to Naples in 1645.[15] In 1645, Leslie, then Imperial Ambassador to Naples, roamed the Italian Peninsula in an attempt to garner funds to fight the war. He is reported to have given Pope Innocent X a solid silver writing table. The trip yielded little money and few troops.[16]

Latter years, Ottoman diplomacy, and death: 1650–1667

[edit]Leslie was made a Field Marshal and the Governor of the Croatian-Slavonian Military Frontier in 1650, an appointment that drew his attention to the Southern reaches of the Holy Roman Empire. During this period, there is evidence that his lifestyle became more relaxed. In the 1650s, Leslie renovated his castles, Nové Město nad Metují in the Kingdom of Bohemia and Ptuj in Slovenia. He also continued a passion of his, collecting and commissioning works of art, especially portraits. He commissioned portraits for Ferdinand II, Ferdinand III, Leopold I and most of their families.[17]

In 1657, he was made Vice-President of the Imperial War Council. He had been an adviser to the Imperial Privy Council for some years. In 1663, he willed his estates and titles to his nephew, James Leslie. In 1665, Walter was made a Knight in the Order of the Golden Fleece. Shortly after that, he embarked on his last diplomatic journey as Imperial Ambassador to Constantinople, a trip that lasted from 1665 until 1666. In Istanbul, he moved along peace treaty talks with Sultan Mehmed IV.[18]

Upon his return in 1666, Leslie's health was failing. He died on 3 March 1667 and was buried in the Scottish Benedictine Abbey in Vienna. Leslie had commissioned the renovation of this very same church years earlier.[19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Worthington, p. 153

- ^ Worthington, p. 154

- ^ Worthington, p. 158

- ^ Worthington, p. 159

- ^ Worthington, p. 160

- ^ Worthington, p. 161

- ^ Worthington, p. 162

- ^ Prendergast (1852), p. 14

- ^ Watson (1938), pp. 404–405

- ^ Watson (1938), pp. 406–407

- ^ Mitchell. pp. 323–345

- ^ Worthington, pp. 167–170

- ^ Worthington, pp. 170–174

- ^ Worthington, p. 206

- ^ Worthington, p. 288

- ^ Worthington, p. 257

- ^ Vidmar (2010), p. 223

- ^ Worthington, pp. 279–282

- ^ Vidmar (2010), p. 218

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Prendergast, Francis. “An Authentic Account of the Death of Wallenstein, with a Vindication of the Motives of Colonel Walter Butler.” Transactions of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, Vol. 2, No. 1 (1852): 9–32.

- Vidmar, Polona. “Under the Habsburgs and Stuarts: The Leslie’s Portrait Gallery in Ptuj castle, Slovenia.” In British and Irish Emigrants and Exiles in Europe, 1603-1688, edited by David Worthington, 215–233. Boston: Brill, 2010.

- Watson, Francis. Wallenstein: Soldier under Saturn. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., 1938), 404–407.

- Worthington, David. Scots in Habsburg Service, 1618-1648. (Boston: Brill, 2004), 153–288.

- Mitchell J. Life of Wallenstein Duke of Friedland, London, James Fraser, 1888; pp. 323–345

Further reading

[edit]- Worthington, David. British and Irish Experiences and Impressions of Central Europe, 1560-1688. Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2012.

- Pages, Georges. The Thirty Years' War 1618-1648. Translated by David Maland and John Hopper. New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

- Guthrie, William P., The Later Thirty Years' War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia. London: Greenwood Press, 2003.

- Worthington, David, "A Stuart-Austrian Habsburg intermediary: The life of Walter Leslie (1606-67)", History Scotland, (July–August 2002), pp. 29–34.

External links

[edit]- 1607 births

- 1667 deaths

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Scottish people of the Thirty Years' War

- Clan Leslie

- Field marshals of the Holy Roman Empire

- Military personnel from Aberdeenshire

- Scottish diplomats

- Scottish soldiers

- Imperial Army personnel of the Thirty Years' War

- People of the War of the Mantuan Succession