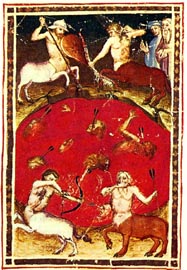

Visio Karoli Grossi

Anonymous Florentine painting, c. 1400

The Visio Karoli Crassi or Visio Karoli Grossi (meaning "Vision of Charles the Fat"), also called the Visio Karoli (Tertii) Imperatoris ("Vision of [Emperor] Charles III"), is an anonymous work of Latin prose from around 900.[1] It was composed at Reims and depicts a vision of his ancestors warning the Emperor Charles the Fat of the coming downfall of his family, the Carolingians.

The work was produced in or near Reims, possibly by someone in the circle of Fulk the Venerable, the Archbishop of Reims, because the Visio credits the intercession of Saints Peter and Remigius (the patron saint of Reims) with preserving the Carolingian line. Fulk was also a Carolingian partisan in 888. Among the works that probably influenced the vision of Charles the Fat prominence can be given to the De visione Bernoldi presbyteri written by Hincmar of Reims in the middle of the ninth century.

Among the ancestors who appear to Charles in his vision are his father, Louis the German; uncle, Lothair I; and cousin, Louis the Younger. He is also visited by Louis the Younger's daughter, Ermengard, and her husband, Boso, and son, Louis of Provence. Charles had recognised the right of the latter to inherit Provence after Boso died on 11 January 887, but Charles himself was deposed in November and died in January 888, leaving the young Louis and his mother without a defender. The Visio appears to have been written as a defence of the young Louis's claim.

The Visio was widely transcribed in the ninth through fifteenth centuries, especially in the High Middle Ages (11th–13th). Versions were inserted into the Gesta Regum Anglorum of William of Malmesbury, the Chronicon Centulense of Hariulf of Oudenbourg, and the anonymous Annals of Saint Neots as pieces of historical information. From Wiliam and Hariulf the story was extracted and placed in the universal Chronicon of Helinand of Froidmont under the year 888 and in the Speculum historiale of Vincent of Beauvais. A complete English translation of the Visio was included in The Birth of Purgatory by Jacques Le Goff as evidence of the need, as early as the ninth century, for a realm lying between Hell and Paradies (i.e. Purgatory) wherein good men could reside in the hereafter.[2]

The Visio may also have been an inspiration to Dante Alighieri. In his Divine Comedy (Inferno, XII, 100–126), in the first ring of the seventh circle of Hell, Dante, guided by Virgil and Nessus, visits those sinners, tiranni / che dier nel sangue e ne l' aver di piglio ("tyrants / who dealt in bloodshed and in pillaging"), who are immersed to varying depths in boiling water. This punishment was not typically ascribed in Dante's age to such sinners, but the Visio attaches it to those who facere praelia et homicidia et rapinas pro cupiditate terrena ("make battle and murder and rapine because of worldly cupidity"). Theodore Silverstein, who first identified the connection between Dante and the Visio, suggests that Dante's apparent interest in contemporary politics would have attracted him to a piece like the Visio. Its popularity assures that Dante would have had access to it.[3]

Sources

[edit]- Dutton, Paul Edward (1994). The Politics of Dreaming in the Carolingian Empire. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1653-X.

- Gardiner, Eileen, Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante (New York: Italica Press, 1989), pp. 129–33, provides an English translation of the Latin text.

- Le Goff, Jacques; Goldhammer, Arthur, tr. (1986). The Birth of Purgatory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-47083-0.

- Lewis, Andrew W. (1981). Royal Succession in Capetian France: Studies on Familial Order and the State. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-77985-1.

- MacLean, Simon (2003). Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schutz, Herbert (2004). The Carolingians in Central Europe, Their History, Arts, and Architecture: A Cultural History of Central Europe, 750–900. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13149-3.

- Silverstein, Theodore (1936). "Inferno, XII, 100–126, and the Visio Karoli Crassi." Modern Language Notes, 51:7 (Nov.), pp. 449–452.

- Silverstein, Theodore (1939). "The Throne of the Emperor Henry in Dante's Paradise and the Mediaeval Conception of Christian Kingship." Harvard Theological Review, 32:2 (Apr.), pp. 115–129.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lewis, 5, places it c. 901, the year of Louis the Blind's imperial coronation; Le Goff places it shortly after Charles' death in 888.

- ^ Le Goff, 118–121. His commentary suggests that the Visio represents a politicising of the otherwolrd, designed to induce favours from the still living.

- ^ For the Dantean connexion and the likelihood that Dante knew of the Visio Karoli Grossi, see Silverstein (1936) and (1939), where he suggests that the image of the "Roman emperors" (Carolingians) sitting on bejewelled thrones in the afterlife would have been to Dante's liking. Le Goff states definitively that ("we know [that]") Dante read it.