Virginia Hall

Virginia Hall Goillot | |

|---|---|

Virginia Hall receiving the Distinguished Service Cross in 1945 from OSS chief General William Donovan | |

| Born | April 6, 1906 |

| Died | July 8, 1982 (aged 76) |

| Burial place | Pikesville, Maryland, US |

| Alma mater | |

| Spouse |

Paul Gaston Goillot (m. 1957) |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service branch | |

| Service years | 1940–1966 |

| Operations | Operation Jedburgh |

| Other work | US Department of State (1931–39) |

Virginia Hall Goillot DSC, Croix de Guerre, MBE (April 6, 1906 – July 8, 1982), code named Marie and Diane, was an American who worked with the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in France during World War II. The objective of SOE and OSS was to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers, especially Nazi Germany. SOE and OSS agents in France allied themselves with resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England. After World War II, Hall worked for the Special Activities Division of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Hall was a pioneering agent for the SOE, arriving in Vichy France on 23 August 1941,[1] the first female agent to take up residence in France. She created the Heckler network in Lyon. Over the next 15 months, she "became an expert at support operations – organizing resistance movements; supplying agents with money, weapons, and supplies; helping downed airmen to escape; offering safe houses and medical assistance to wounded agents and pilots."[2] She fled France in November 1942 to avoid capture by the Germans.

She returned to France as a wireless operator for the OSS in March 1944 as a member of the Saint network. Working in territory still occupied by the German army and mostly without the assistance of other OSS agents, she supplied arms, training, and direction to French resistance groups, called Maquisards, especially in Haute-Loire where the Maquis cleared the department of German soldiers prior to the arrival of the American army in September 1944.

The Germans gave her the nickname Artemis, and the Gestapo reportedly considered her "the most dangerous of all Allied spies."[3] Having lost part of her left leg after a hunting accident, Hall used a prosthesis she named "Cuthbert." She was also known as "The Limping Lady" by the Germans and as "Marie of Lyon" by many of the SOE agents she assisted.

Virginia Hall left no memoir, granted no interviews, and spoke little about her overseas life--even with relatives. She...received our country's Distinguished Service Cross, the only civilian woman in the Second World war to do so. But she refused all but a private ceremony with OSS chief Donovan--even a presentation by President Truman.[4]

She was a thirty-five-year-old journalist from Baltimore, conspicuous by reddish hair, a strong American accent, an artificial foot, and an imperturbable temper; she took risks often but intelligently.[5]

I would give anything to get my hands on that limping Canadian [sic] bitch.[6]

Early life

[edit]Virginia Hall was born in Baltimore, Maryland on April 6, 1906, to Edwin "Ned" Lee Hall and his wife (also his secretary), Barbara Virginia Hammel.[7][8] Ned Hall's father, John W. Hall, had stowed away on his father's clipper ship at the age of nine, and later became a wealthy businessman. She had a brother, John, four years her senior. Virginia was close to her family members, who affectionately nicknamed her "Dindy".[8]

In 1912, Hall began attending Roland Park Country School, where during her high school years, she became editor-in-chief of her school's yearbook, Quid Nunc; and became class president in her senior year.[8] After graduating, she attended Radcliffe College of Harvard University and Barnard College of Columbia University, where she studied French, Italian, and German.[7] She also attended George Washington University, where she studied French and Economics. She wanted to finish her studies in Europe, so she traveled the Continent and studied in France, Germany, and Austria, eventually landing an appointment as a Consular Service clerk at the Embassy of the United States, Warsaw, Poland in 1931.

A few months later she transferred to Smyrna (İzmir), Turkey. In 1933, she tripped on a fence and accidentally shot herself in the left foot while hunting birds. After being diagnosed with gangrene, on the brink of death, as a last-ditch attempt her leg was amputated below the knee and replaced with a wooden appendage which she named "Cuthbert". She then worked again as a consular clerk in Venice and in Tallinn, Estonia.[9]

Hall made several attempts to become a diplomat with the United States Foreign Service, but women were rarely hired. In 1937, she was turned down by the Department of State because of an obscure rule against hiring people with disabilities as diplomats. An appeal for her to be hired to President Franklin D. Roosevelt was unheeded. She resigned from the Department of State in March 1939, still a consular clerk.[10]

World War II

[edit]Early in World War II in February 1940, Hall became an ambulance driver for the French army. After the defeat of France in June 1940, she made her way to Spain where, by chance, she met a British intelligence officer named George Bellows. Bellows was impressed with her and gave her the telephone number of a "friend" who might be able to help her find employment in England. That friend was Nicolas Bodington, who worked for the newly created Special Operations Executive (SOE).[7][11]

Special Operations Executive

[edit]Hall joined the SOE in April 1941 and after training arrived in Vichy France, unoccupied by Germany and nominally independent at that time, on August 23, 1941. She was the second female agent to be sent to France by SOE's F (France) Section, and the first to remain there for a lengthy period of time. (SOE F section would send 41 female agents to France during World War II, of whom 26 would survive the war.)[a] Hall's cover was as a reporter for the New York Post which gave her license to interview people, gather information and file stories filled with details useful to military planners. She based herself in Lyon. She turned away from her "chic Parisian wardrobe" to become inconspicuous and often quickly changed her appearance through make-up and disguise.[13] Hall was a pioneer as a World War II secret agent and had to learn on her own the "exacting tasks of being available, arranging contacts, recommending who to bribe and where to hide, soothing the jagged nerves of agents on the run and supervising the distribution of wireless sets."[14] The network (or circuit) of SOE agents she founded was named Heckler.[15] Among her recruits were gynecologist Jean Rousset and Germaine Guérin, the owner of a prominent brothel in Lyon. Guérin made several safehouses available to Hall and passed along tidbits of information she and her female employees heard from German officers visiting the brothel.[16]

The official historian of the SOE, M. R. D. Foot, said that the motto of every successful secret agent was "dubito, ergo sum" ("I doubt, therefore I am.").[17] Hall's lengthy tenure in France without being captured illustrates her caution. In October 1941, she sensed danger and declined to attend a meeting of SOE agents in Marseille which the French police raided, capturing a dozen agents. After that debacle, Hall was one of the few SOE agents still at large in France and the only one with a means of transmitting information to London. George Whittinghill, an American diplomat in Lyon, allowed her to smuggle reports and letters to London in the diplomatic pouch.[18]

The winter of 1941–42 was miserable for Hall. In a letter she said that if SOE would send her a piece of soap she would be "both very happy and much cleaner." In the absence of an SOE wireless operator, her access to the American diplomatic pouch was the only means the few agents left at large in France had of communicating with London. She continued building contacts in southern France and she assisted in the brief missions of SOE agents Peter Churchill and Benjamin Cowburn and earned high compliments from both. She avoided contact with an SOE agent sent to Lyon named Georges Duboudin and refused to introduce him to her contacts. She regarded him as amateurish and lax in security. When SOE headquarters directed that Duboudin should supervise her, she told SOE to "lay off." She worked as little as possible with Philippe de Vomécourt, who, although an authentic French Resistance leader, was lax in security and grandiose in his ambitions.[19] In August 1942, SOE agent Richard Heslop met with her and described her as a "girl" (she was 36) who lived in a gloomy apartment, but he relied on her to facilitate communications with other agents. When a suspicious Heslop demanded to know who "Cuthbert" was she showed him by banging her wooden foot against a table leg producing a hollow sound.[20]

Another task Hall took on was helping British airmen who'd been shot down or crashed over Europe to escape and return to England. Downed airmen who found their way to Lyon were told to go to the American Consulate and say they were a "friend of Olivier." "Olivier" was Hall and she, with the help of brothel-owner Guérin and other friends, hid, fed, and helped dozens of airmen escape France to neutral Spain and hence back to England.[21]

The French nicknamed her "la dame qui boite" and the Germans put "the limping lady" on their most wanted list.[7]

The jailbreak

[edit]Hall learned that the 12 agents arrested by the French police in October 1941 were incarcerated at Mauzac prison near Bergerac. Wireless operator Georges Bégué smuggled out letters to Hall from the prison and she recruited Gaby Bloch, wife of the prisoner Jean-Pierre Bloch, as an ally to plan an escape. Bloch visited the prison frequently to bring food and other items to her husband, including tins of sardines. The sardine tins and the tools she smuggled in enabled Bégué to make a key to the door of the barracks where the prisoners were kept. Hall, too well known to visit the prison, assembled safe houses, vehicles, and helpers. A priest smuggled a radio in to Bégué, and he began transmitting to London from within the prison.

The prisoners escaped on July 15, 1942 and, after hiding in the woods while an intense manhunt took place, all met up with Hall in Lyon by August 11. From there, they were smuggled to Spain and thence back to England.[22] The official historian of SOE, M. R. D. Foot, called the escape "one of the war's most useful operations of its kind." Several of the escapees returned later to France and became leaders of SOE networks.[23]

Germany retaliates

[edit]The Germans were furious about the escape from Mauzac prison and the laxity of the French police in allowing the escape. The Gestapo flooded Vichy, France with 500 agents, and the Abwehr also stepped up operations to infiltrate and destroy the fledgling French Resistance and the SOE networks. The Germans focused on Lyon, the center of the resistance. Hall had counted on contacts she had with the French police to protect her, but, under pressure from the Germans, her police contacts were no longer reliable.[24]

In May 1942, Hall had agreed to have messages from the Gloria Network, a French-run resistance movement based in Paris, transmitted to SOE in London. Gloria was infiltrated in August by a Roman Catholic priest and Abwehr agent named Robert Alesch, and the Abwehr captured its leadership. Alesch also made contact with Hall in August, claiming to be an agent of Gloria and offering intelligence of apparently high value. She had doubts about Alesch, especially when she learned that Gloria had been destroyed, but was persuaded of his bona fides, as was the London headquarters of SOE. Alesch was able to penetrate Hall's network of contacts, including the capture of wireless operators and the sending of false messages to London in her name.[25][26]

Escape

[edit]On November 7, 1942, the American Consulate in Lyon told Hall that an Allied invasion of North Africa was imminent. In response to the invasion, on November 8, the Germans moved to occupy Vichy, France. Hall anticipated correctly that the suppression by the Gestapo and Abwehr would become even more severe and she fled Lyon without telling anyone, including her closest contacts. She escaped by train from Lyon to Perpignan, then, with a guide, walked over a 7,500 foot pass in the Pyrenees to Spain, covering up to 50 miles over two days in considerable discomfort.[27][28]

Hall signaled to SOE before her escape that she hoped that "Cuthbert" would not trouble her on the way. The SOE did not understand the reference and replied, "If Cuthbert troublesome, eliminate him." After arriving in Spain, she was arrested by the Spanish authorities for illegally crossing the border, but the American Embassy eventually secured her release. She worked for SOE for a time in Madrid, then returned to London in July 1943 where she was quietly made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).[29][30]

Office of Strategic Services

[edit]

On her return to London, SOE leaders declined to send Hall back to France as an agent, despite her requests that they do so. She was compromised, they said, and too much at risk. However, she took a wireless course and contacted the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) about a job. She was hired by the Special Operations Branch at the low rank and pay of a second lieutenant, and she returned to France on March 21, 1944, arriving by motor gunboat at Beg-an-Fry east of Roscoff in Brittany. Her artificial leg prevented her from parachuting.

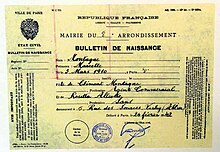

OSS provided her with a forged French identification card in the name of Marcelle Montagne. Her codename was Diane. The OSS teams' objective was to arm and train the resistance groups, called Maquis, so they could conduct sabotage and guerrilla activities to support the Allied invasion of Normandy, which would take place on June 6, 1944.[31][32]

Hall was disguised as an older woman, with gray hair and her teeth filed down to resemble that of a peasant woman. She disguised her limp with the shuffle of an old woman. Landing with her was Henri Lassot, 62 years old. Lassot was the organiser and leader of the new Saint network, it being too radical a thought that a woman could lead an SOE or OSS network of agents. She was Lassot's wireless operator. They were the fourth and fifth OSS agents to arrive in France. Lassot carried with him one million francs, equivalent to 5,000 British pounds; Hall had 500,000 francs with her. Hall quickly separated herself from Lassot, whom she characterized as too talkative and a security risk, instructing her contacts not to tell him where she was. Aware that her accent would reveal that she was not French, she engaged a French woman, Madame Rabut, to accompany and speak for her.[33]

From March to July 1944, Hall roamed around France south of Paris, posing sometimes as an elderly milkmaid (and on one occasion selling cheese she had made to a group of German soldiers). She found and organized drop zones, established several safe houses, and made and renewed contacts in the Resistance, notably with Philippe de Vomecourt. She organized and supplied with arms several resistance groups of a hundred men each in the Cher and Cosne. She unsuccessfully attempted to organize a jailbreak to gain freedom for three men she called her nephews, captives of the Germans in Paris. Her resistance groups undertook many successful small-scale attacks on infrastructure and German soldiers.[34][35]

Hall was next given the job of helping the Maquis in southern France harass the Germans in support of the Allied invasion of the south, Operation Dragoon, which would take place on August 15, 1944. In July, Hall was ordered to go to Haute-Loire department, arriving July 14, quitting her disguise, and establishing her headquarters in a barn near Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. As a woman with the rank of second lieutenant she had problems asserting her authority over the Maquis groups and the self-proclaimed colonels heading them. She complained to OSS headquarters, "you send people out ostensibly to work with me and for me, but you do not give me the necessary authority."[36]

She told the Maquis leaders that she would finance them and give them arms on condition that they would be advised by her, but the prickly Maquis leaders continued to be a problem.[37] The three planeloads of supplies she received in late July and the money she distributed for expenses gained their grudging acquiescence.

The three battalions of Maquisards (about 1,500 men) in her area undertook a number of successful sabotage operations. Now part of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI), they forced the German occupiers to withdraw from Le Puy-en-Velay and head north with the rest of the retreating German forces. Belatedly, a Jedburgh team of three men, called Jeremy, parachuted in on August 25 to undertake the training and supply of the battalions.[38] Hall commented wryly, "this was after the Germans had been liquidated in the department of the Haute Loire and Le Puy liberated."[39]

Hall and several of the British and American military officers working for her left the Haute Loire and arrived in Paris on September 22. Later, she and her OSS agent Paul Golliot journeyed to Austria to foment anti-Nazi resistance. With the collapse of the Nazis, Hall and Golliot returned to Paris in April 1945. She wrote reports, and identified people who had helped her and were deserving of commendations, then resigned from the OSS.[40][41]

Postwar and death

[edit]After the war, Hall visited Lyon to learn the fate of the people who had worked for her there. Her closest associates, brothel-owner Germaine Guérin and gynecologist Jean Rousset, had both been captured by the Germans and sent to concentration camps, but they survived. She arranged 80,000 francs (400 British pounds) compensation from the United Kingdom for Guérin, but most of her other helpers received nothing. Many of the people she knew had not survived, including the three men she had called "nephews," who had been executed at Buchenwald.[42] Robert Alesch, the German agent and priest who had betrayed her network in Lyon, was captured after the war and executed in Paris.[26]

Hall joined the Central Intelligence Agency in 1947, one of the first women hired by the new agency. As a woman, she was discriminated against, as the CIA later acknowledged. She was passed over for promotions, honors, and work for which she was qualified, despite the support and efforts from her superiors who knew her work directly. She was given a desk-bound job as an intelligence analyst, to gather information about Soviet penetration of European countries. She resigned in 1948, and then was rehired in 1950 for another desk job.

In the 1950s, she again headed ultra secret paramilitary operations in France as a model for setting up resistance groups in several European countries in case of a Soviet attack. She became a "sacred" presence and the first woman operations officer in the entire covert action arm of the CIA, and a valued member of the Special Activities Division supporting undercover activities to prevent the spread of communism in Europe. She received a poor performance report from a superior who had never overseen her work. In 1966, she retired, at the mandatory retirement age of 60.

In the secret CIA report of her career, the CIA admitted that her fellow officers "felt she had been sidelined--shunted into backwater accounts because she had so much experience that she overshadowed her male colleagues, who felt threatened by her," and that "her experience and abilities were never properly utilized."[43]

While in Haute-Loire, Hall had met and fallen in love with an OSS lieutenant, Paul Goillot, who worked with her. In 1957, the couple married after living together off-and-on for years. They retired to a farm in Barnesville, Maryland, where she lived until her death. She died on July 8, 1982, at Adventist Hospital in Rockville, Maryland. Her husband survived her by five years.[44] She is buried in the Druid Ridge Cemetery, Pikesville, Maryland.

Awards

[edit]General William Joseph Donovan personally awarded Virginia Hall a Distinguished Service Cross in September 1945 in recognition of her efforts in France. This was the only DSC awarded to a civilian woman in World War II.[45][46] President Truman wanted a public award of the medal, but Hall demurred, stating that she was "still operational and most anxious to get busy." She was made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE), and was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palme by France.[47]

Hall's refusal to talk and write about her World War II experiences resulted in her slipping into obscurity during her lifetime, but her death "triggered a new curiosity" which persisted into the 21st century.[48]

In 1988 her name was added to the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame.[49] The French and British ambassadors in Washington honored her in 2006, on the 100th anniversary of her birth.[50][51] In 2016, a CIA field agent training facility was named the Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center.[52][page needed] The CIA Museum gives five operatives individual sections in its catalog. One is Virginia Hall; the other four are men who went on to head the CIA.[52][page needed] She was inducted into the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame in 2019.[53]

Legacy

[edit]Books

[edit]Her story has been told in several books, including:

- Nouzille, Vincent (2007). L'Espionne, Virginia Hall, une Américaine dans la guerre [The Spy, Virginia Hall, an American in the war] (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-62827-1. OCLC 175652461.[54]

- Gralley, Craig R. (2019). Hall of Mirrors: Virginia Hall: America's Greatest Spy of WWII. Chrysalis Books, LLC. ISBN 978-1-7335415-0-3. OCLC 1098215206.[55]

- Mitchell, Don (2019). The Lady Is a Spy: Virginia Hall, World War II Hero of the French Resistance. New York, NY: Scholastic Focus. ISBN 978-0-545-93612-5. OCLC 1034621511, a non-fiction book for ages 12–18.[56]

- Polette, Nancy (2012). The Spy with the Wooden Leg: The Story of Virginia Hall. St. Paul, MN: Alma Little. ISBN 978-1-934617-15-1. OCLC 1285859639, a non-fiction book for ages 10 and older.[57]

- Pearson, Judith L. (2005). The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-62681-292-5. OCLC 893688998.

- Purnell, Sonia (2019). A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II. New York: Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. ISBN 978-0-7352-2530-5. OCLC 1081338820.

- Demetrios, Heather (2021). Code name Badass: the true story of Virginia Hall. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5344-3189-8. OCLC 1267517106, audience: ages 14 and up.

Roger Wolcott Hall (no relation) also mentioned her in passing in his book You're Stepping On My Cloak And Dagger. New York: W.W. Norton. 1957. OCLC 1084750854. (Reprinted: ISBN 978-1-61251-371-3)

Films

[edit]IFC Films released A Call to Spy in October 2020, the first feature film about Virginia Hall.[58] It had its world premiere at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in June 2019, commemorating the 75th anniversary of D-Day.[59][60][61] Hall is portrayed by Sarah Megan Thomas, and the film is directed by Lydia Dean Pilcher. The film went on to win the Audience Choice Award in Canada.[62] A Call to Spy had its U.S. festival premiere at the 2020 Santa Barbara International Film Festival, where it was honored with the Anti-Defamation League's "Stand Up" Award.[63]

The film A Woman of No Importance was announced in 2017, based on the book by Sonia Purnell[64] and starring Daisy Ridley as Hall.[65][66]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Vigurs, Kate (2021). Mission France: The True History of the Women of SOE. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 42. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1mgmd86. ISBN 978-0-300-25884-4. OCLC 1250089467. S2CID 243273078.

- ^ Gralley 2017, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Meyer, Roger (October 2008). "World War II's Most Dangerous Spy". The American Legion Monthly. American Legion: 54. ISSN 2766-5054. OCLC 1781656.

- ^ Gralley 2017, pp. 5.

- ^ Foot 1966, p. 170.

- ^ Gralley 2017, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Ramul, Aaja (February 4, 2009). "Not Bad for a Girl from Baltimore: the Story of Virginia Hall" (PDF). photos.state.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Don (2019). The Lady is a Spy: Virginia Hall, World War II Hero Of The French Resistance (PDF). Scholastic Publishing. p. 2.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 12–21.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 13–29.

- ^ Foot 1966, pp. 465–469.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 39–40, 46–47.

- ^ Foot 1966, p. 171.

- ^ Gralley 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Foot 1966, p. 311.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 47, 52–53.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 69–89, 99–100.

- ^ Heslop, Richard (2014) [1970]. Xavier: A British Secret Agent with the French Resistance. London, England: Biteback Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-84954-774-1. OCLC 884013767.

- ^ Purnell 2019, p. 64.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 113–126.

- ^ Foot 1966, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 127–137.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 144–152.

- ^ a b Bourrée, Fabrice. "Gabrielle Jeanine Picabia, chef du réseau Gloria SMH" [Gabrielle Jeanine Picabia, head of the Gloria SMH network]. Musée de la résistance en ligne (in French). Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ Gralley 2017, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 158–159.

- ^ "Special Operations". Central Intelligence Agency. May 6, 2007. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- ^ "Virginia Hall MBE Medal Award". International Spy Museum. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 191–193, 197.

- ^ Rossiter 1986, pp. 102–193.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 197–199, 203–206, 209.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 189, 207–208, 222–223.

- ^ F-Section, Saint Heckler 1944.

- ^ Rossiter 1986, pp. 196–197.

- ^ F-Section, Saint Heckler 1944, p. 1168.

- ^ Rossiter 1986, pp. 195–196.

- ^ F-Section, Saint Heckler 1944, p. 1169.

- ^ Purnell 2019, p. 267.

- ^ Escott 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 257, 291, 294–297, 300–305.

- ^ Purnell 2019, pp. 307, 311.

- ^ "Today's Document from the National Archives". Archives.gov. October 19, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

Memorandum for the President from William J. Donovan Regarding Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) Award to Virginia Hall, 05/12/1945

- ^ "Today's Document » May 12 – Virginia Hall of the OSS". archives.gov. October 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011.

- ^ Shapira, Ian (July 11, 2017). "The Nazis were closing in on a spy known as 'The Limping Lady.' She fled across mountains on a wooden leg". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Purnell 2019, p. 307.

- ^ Purnell 2019, p. 309.

- ^ Nuckols, Ben (December 10, 2006). "Ambassadors to honor female WWII spy". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 20, 2006.

- ^ Tucker, Abigail (December 14, 2006). "A spy gets her due". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ a b Purnell 2019.

- ^ "Virginia Hall, Maryland Women's Hall of Fame". msa.maryland.gov. 2019. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021.

- ^ Foot, M.R.D. (April 21, 2009). "L'espionne: Virginia Hall, une Americaine dans la guerre". cia.gov. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020.

- ^ Shapira, Ian (December 29, 2017). "She was a legendary spy. He worked for three CIA directors. Now he's writing a novel in her voice". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "The Lady is a Spy". kids.scholastic.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019.

- ^ "The Spy with the Wooden Leg". Elva Resa Publishing. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ Willingham, AJ (April 20, 2019). "CIA spy Virginia Hall is about to become everyone's next favorite historical hero". CNN. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Liberté: A Call to Spy". Edinburgh International Film Festival. 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "LIBERTÉ: A CALL TO SPY – World Premiere at Edinburgh Film Festival". reviewsphere.org.

- ^ "'Liberte: A Call To Spy' Will Debut At Edinburgh International Film Festival". Top 10 Films. May 30, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "WFF19 Wraps". Whistler Film Festival. December 10, 2019. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Meisel, Dan (January 9, 2020). "Film 'Liberté: A Call to Spy' Wins Anti-Defamation League Stand Up Award". Noozhawk.com. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (January 24, 2017). "Daisy Ridley to Star in Spy Movie 'A Woman of No Importance' for Paramount". Variety. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Almassi, Hannah (February 9, 2021). "Daisy Ridley on the 'Massive Quiet' of Star Wars Ending and What's Next". Who What Wear. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Dufresne, Alessa (February 22, 2021). "Daisy Ridley Says 'Never Say Never' to a 'Star Wars' Return". Inside the Magic. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

Sources

[edit]- "Activity Report of Virginia Hall (Diane), Saint-Heckler Circuit reports, F Section" (PDF). 801492.org. 1944. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2021.

- Escott, Beryl E. (2010). "Virginia Hall". Heroines of the SOE : Britain's secret women in France. Stroud: History. pp. 34–38. ISBN 978-0-7524-5661-4. OCLC 1302079784 – via Internet Archive.

- Foot, M. R. D. (1966). SOE in France: An Account of the Work of the British Special Operations Executive in France, 1940-1944. London: H.M. Stationery Office. OCLC 600516475.

- Reprinted: Foot, M. R. D. (2004). SOE in France: An Account of the Work of the British Special Operations Executive in France, 1940-1944. doi:10.4324/9780203496138. OCLC 56550748. ISBN 978-0-203-49613-8, 978-0-429-23352-4.

- Gralley, Craig R. (March 2017). "A Climb to Freedom: A Personal Journey in Virginia Hall's Steps" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 61 (1). Washington, DC: CSI: 1–5. ISSN 1942-8510. OCLC 163640801. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 17, 2022.

- Purnell, Sonia (2019). A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II. New York, New York: Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. ISBN 978-0-7352-2530-5. OCLC 1081338820. Partial preview of A Woman of No Importance at Google Books

- Rossiter, Margaret L. (1986). Women in the resistance. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-005339-9. OCLC 185434650.

Further reading

[edit]- Binney, Marcus (2003) [2002]. "Chapter 4: Virginia Hall". The Women Who Lived for Danger: The Women Agents of SOE in the Second World War. Bath: Chivers Press. pp. 135–169, and passim. ISBN 978-0-7540-1936-7. OCLC 1245993527 – via Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]- Davenport-Hines, Richard (March 21, 2019). "A Woman of No Importance by Sonia Purnell review - Virginia Hall, the one-legged female spy who beat the Gestapo". The Times. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- Myre, Greg (April 18, 2019). "'A Woman Of No Importance' Finally Gets Her Due". NPR. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- National Archives (UK) (December 18, 2008). "Special Operations Executive Personnel Files: Virginia HALL, aka Mary HALL - born 06.04.1906".

- "Special Operations". cia.gov. May 6, 2007. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- "The People of the CIA ... Making an Impact: Virginia Hall". cia.gov. August 13, 2007. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008.

- Virginia Hall at Find a Grave

- 1906 births

- 1982 deaths

- 20th-century American writers

- American University alumni

- American amputees

- American anti-communists

- American shooting survivors

- American spies

- American women civilians in World War II

- Analysts of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Barnard College alumni

- Burials at Druid Ridge Cemetery

- Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Female recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France)

- Female resistance members of World War II

- Female wartime spies

- French Resistance members

- Honorary members of the Order of the British Empire

- New York Post people

- People from Baltimore

- People of the Central Intelligence Agency

- People of the Office of Strategic Services

- Radcliffe College alumni

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France)

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States)

- Special Operations Executive personnel

- World War II spies for the United States