Heel (professional wrestling)

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

In professional wrestling, a heel (also known as a rudo in lucha libre) is a wrestler who portrays a villain, "bad guy",[1]"baddie", "evil-doer", or "rulebreaker", and acts as an antagonist[2][3][4] to the faces, who are the heroic protagonist or "good guy" characters. Not everything a heel wrestler does must be villainous: heels need only to be booed or jeered by the audience to be effective characters, although most truly successful heels embrace other aspects of their devious personalities, such as cheating to win or using foreign objects. "The role of a heel is to get 'heat,' which means spurring the crowd to obstreperous hatred, and generally involves cheating and any other manner of socially unacceptable behavior."[5]

To gain heat (with boos and jeers from the audience), heels are often portrayed as behaving in an immoral manner by breaking rules or otherwise taking advantage of their opponents outside the bounds of the standards of the match. Others do not (or rarely) break rules, but instead exhibit unlikeable, appalling, and deliberately offensive and demoralizing personality traits such as arrogance, cowardice, or contempt for the audience. Many heels do both, cheating as well as behaving nastily. No matter the type of heel, the most important role is that of the antagonist, as heels exist to provide a foil to the face wrestlers. If a given heel is cheered over the face, a promoter may opt to turn that heel to face or the other way around, or to make the wrestler do something even more despicable to encourage heel heat. Some performers display a mixture of both positive and negative character traits. In wrestling terminology, these characters are referred to as tweeners (short hand for the "in-between" good and evil actions these wrestlers display). WWE has been cited as a company that is doing away with the traditional heel/face format due in part to audiences' willingness to cheer for heels and boo babyfaces.[6]

In "local" wrestling (e.g., American wrestling) it was common for the faces to be "local" (e.g., Hulk Hogan, John Cena, and Stone Cold Steve Austin) and the heels to be portrayed as "foreign" (e.g., Gunther, Alberto Del Rio, Ivan Koloff, The Iron Sheik, Rusev/Miro, Jinder Mahal, and Muhammad Hassan).[7]

In the world of lucha libre wrestling, most rudos are generally known for being brawlers and for using physical moves that emphasize brute strength or size, often having outfits akin to demons, devils, or other tricksters. This is contrasted with most heroic técnicos that are generally known for using moves requiring technical skill, particularly aerial maneuvers.[8]

History

[edit]Common heel behavior includes cheating to win (e.g. using the ropes for leverage while pinning or attacking with a weapon while the referee is looking away), employing dirty tactics such as blatant chokes or raking the eyes, attacking other wrestlers backstage, interfering with other wrestlers' matches, insulting the fans or city they are in (referred to as "cheap heat") and acting in a haughty or superior manner.[9]

More theatrical heels would feature dramatic outfits giving off a nasty or otherwise dangerous look, such as wearing corpse paint over their faces, putting on demonic masks, covering themselves in dark leather and the like. Gorgeous George is regarded as the father of the wrestling gimmick, and by extension the heel gimmick. Starting in the 1940s, he invented an extravagant, flamboyant "pretty boy" gimmick who wore wavy blonde hair, colorful robes and ritzy outfits, and was accompanied by beautiful valets to the ring for his matches. The crowd widely jeered his persona, and came out to his matches in hopes of seeing him defeated.[10] George relished this attention, and exploded into one of the most famous (and hated) heels not only of his era, but of all time. Another example of a dramatic heel is the wrestler The Undertaker, who, on many occasions throughout his career, has switched between portraying a heel or a face.[11] During his period as the leader of The Ministry of Darkness, he appeared as a priest of the occult in a hooded black robe and literally sat in a throne,[12] often in the shape of the symbol used to represent him.

Occasionally, faces who have recently turned from being heels still exhibit characteristics from their heel persona.[13] This occurs due to fans being entertained by a wrestler despite (or because of) their heel persona, often due to the performer's charisma or charm in playing the role. Certain wrestlers such as Eddie Guerrero[14] and Ric Flair gained popularity as faces by using tactics that would typically be associated with heels, while others like Stone Cold Steve Austin, Scott Hall and more recently Becky Lynch[15] displayed heelish behavior during their careers yet got big face reactions, leading them to be marketed as antiheroes.

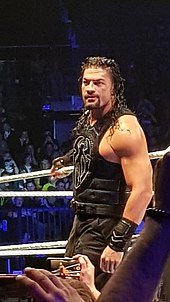

On other occasions, wrestlers who are positioned as faces receive a negative audience reaction despite their portrayal as heroes. An example is Roman Reigns, who in 2018 was a top face in WWE, but got booed in his matches while his opponents got cheered regardless of their status as face or heel, due to perceived favoritism from WWE executives and a lack of character development. Such characters often (but not always) become nudged into becoming villains over time or retooled to present a different public image, such as The Rock's turn from a clean-cut face to self-absorbed narcissist in the Nation of Domination heel stable,[16] or Tetsuya Naito's fan rejection of his babyface causing him to drastically form Los Ingobernables de Japon. The term "heel" does not, in itself, describe a typical set of attributes or audience reaction, but simply a wrestler's presentation and booking as an antagonist.

Depending on the angle, heels can act cowardly or overpowering to their opponents. For instance, a "closet champion" in particular is a term for a heel in possession of a title belt who consistently dodges top flight competition and attempts to back down from challenges. Examples include Seth Rollins during his first WWE World Heavyweight Championship reign, Charlotte during her Divas/Raw Women's Championship reign, the Honky Tonk Man during his long Intercontinental Championship reign, Tommaso Ciampa during his NXT Championship reign and The IIconics during their WWE Women's Tag Team Championship reign. Brock Lesnar's character in WWE had heel aspects, and was well known for failing to regularly defend his title (especially during his first Universal Championship reign), often only performing on pay-per-view events and not on SmackDown or especially Raw as he was only on a part-time appearance contract with WWE.[17][18] This sort of behavior supports the intended kayfabe opinion that the face (or faces) the heel is feuding with is actually more deserving of the title than the title-holding heel is. Heels may beg for mercy during a beat down at the hands of faces, even if they have delivered similar beat downs with no mercy. Ric Flair in particular has been well known for begging an opponent off, then hitting a low blow on his distracted opponent. Other heels may act overpowering to their opponents to play up the scrappy underdog success story for the face.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Oz, Drake. "Understanding Wrestling Terminology: A Casual Fan's Guide". Bleacher Report. Turner Inc. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Torch Glossary of Insider Terms". PWTorch.com. 2000. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ Foley, Mick. Have A Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks (p. 2).

- ^ Sammond, Nicholas (2005). Steel Chair to the Head. Duke University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-8223-3438-5.

- ^ Edison, Mike (4 September 2017). "The Art of the Heel". The Baffler. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Ostriecher, Blake. "5 Reasons WWE No Longer Has True Heels Or Babyfaces". Forbes. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Esbenshade, Ellie (15 April 2019). "The Geeky Historian: What Happened to Foreign Heels in Wrestling?". The Geeky Historian. Medium. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Cocking, Lauren (5 November 2016). "Everything You Need to Know about Wrestling". Culture Trip. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Foley, Mick. Have A Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks (p. 117).

- ^ Jares, Joe. "George was Villainous, Gutsy, and Gorgeous". Sports Illustrated Vault | Si.com. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Mueller, Chris. "Examining Undertaker's Legacy as the Measuring Stick for Every WWE Superstar". Bleacher Report. Turner Inc. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Wagoner, Christopher (16 August 2019). "WWE History Vol. 9: Wrestling's greatest stables". Sportskeeda. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Powell, John. "'WWE WrestleMania XX' Results". Slam! Sports. Canadian Online Explorer. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ Baker, Will. "WWE: 10 Wrestlers That Work Better as Faces Than as Heels". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Martinez, Phillip (20 August 2018). "Did Becky Lynch Turn Heel? It's More Complicated Than That". Newsweek. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Hayner, Chris. "22 Massive WWE Heel Turns Every Fan Had Better Know". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Sidle, Ryan (29 November 2019). "WWE Champion Brock Lesnar Will Not Fight Again This Year". SPORTBible. CONTENTbible. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Matthews, Graham GSM. "Analyzing Brock Lesnar's Part-Time Schedule and Why It Works for WWE". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

References

[edit] Media related to Heel (professional wrestling) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Heel (professional wrestling) at Wikimedia Commons- Mick Foley (2000). Have A Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks. HarperCollins. p. 511. ISBN 0-06-103101-1.