Verapamil

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /vɛˈræpəmɪl/ ve-RAP-ə-mil |

| Trade names | Isoptin, Calan, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684030 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Calcium channel blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35.1% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Onset of action | 1 to 2 hours (oral); 3 to 5 minutes (IV bolus)[6][7] |

| Elimination half-life | 2.8–7.4 hours[8] |

| Excretion | Kidney: 11% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.133 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

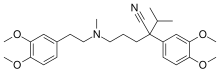

| Formula | C27H38N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 454.611 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Verapamil, sold under various trade names,[1] is a calcium channel blocker medication used for the treatment of high blood pressure, angina (chest pain from not enough blood flow to the heart), and supraventricular tachycardia.[9] It may also be used for the prevention of migraines and cluster headaches.[10][11] It is given by mouth or by injection into a vein.[9]

Common side effects include headache, low blood pressure, nausea, and constipation.[9] Other side effects include allergic reactions and muscle pains.[12] It is not recommended in people with a slow heart rate or heart failure.[12] It is believed to cause problems for the fetus if used during pregnancy.[2] It is in the non–dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker family of medications.[9]

Verapamil was approved for medical use in the United States in 1981.[9][13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] Verapamil is available as a generic medication.[9] Long acting formulations exist.[12] In 2022, it was the 188th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[15][16]

Medical uses

[edit]Verapamil is used for controlling ventricular rate in supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and migraine headache prevention.[17]

Verapamil is also used for the treatment of angina (chronic stable, vasospastic or Prinzmetal variant), unstable angina (crescendo, preinfarction), and for the prevention of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT).[18]

Verapamil is a class-IV antiarrhythmic and more effective than digoxin in controlling ventricular rate.[19] Verapamil is not listed as a first line antihypertensive agent by the guidelines provided by JAMA in JNC-8.[20] However, it may be used to treat hypertension if patient has co-morbid atrial fibrillation or other types of arrhythmia.[17][21]

Verapamil is used intra-arterially to treat cerebral vasospasm.[22] It is also used to treat cluster headaches.[23] Tentative evidence supports the use of verapamil topically to treat plantar fibromatosis.[24]

Use of verapamil in people with recent onset of type 1 diabetes may improve pancreatic beta cell function. In a 2023 meta-analysis[25] involving data from two randomized controlled trials (113 patients with recent onset type-1 diabetes), it was demonstrated that the use of verapamil over one year was associated with significantly higher C-peptide area under the curve levels. Higher C-peptide levels means better pancreatic insulin production and beta cell function.[25]

Verapamil has been reported to be effective in both short-term[26] and long-term treatment of mania and hypomania.[27] Addition of magnesium oxide to the verapamil treatment protocol enhances the antimanic effect.[28]

Contraindications

[edit]Use of verapamil is generally avoided in people with severe left ventricular dysfunction, hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg), cardiogenic shock, and hypersensitivity to verapamil.[4] It is also contraindicated in people with atrial flutter or fibrillation and an existing accessory tract such as in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.[29][4]

Side effects

[edit]The most common side effect of verapamil is constipation (7.3%). While the definite mechanism by which verapamil causes constipation has not been studied, studies have been conducted to rule out mechanisms of actions that might yield this adverse effect. A study by The National Library of Medicine called "Effect of Verapamil on the Human Intestinal Transit" found that verapamil affects the colon but not the upper gastrointestinal tract.[30]

Other side effects include dizziness (3.3%), nausea (2.7%), low blood pressure (2.5%), and headache 2.2%. Other side effects seen in less than 2% of the population include: edema, congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, diarrhea, fatigue, elevated liver enzymes, shortness of breath, low heart rate, atrioventricular block, rash and flushing.[4] Along with other calcium channel blockers, verapamil is known to induce gingival enlargement.[31]

Overdose

[edit]Acute overdose is often manifested by nausea, weakness, slow heart rate, dizziness, low blood pressure, and abnormal heart rhythms. Plasma, serum, or blood concentrations of verapamil and norverapamil, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities. Blood or plasma verapamil concentrations are usually in a range of 50–500 μg/L in persons on therapy with the drug, but may rise to 1–4 mg/L in acute overdose patients and are often at levels of 5–10 mg/L in fatal poisonings.[32][33]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Verapamil's mechanism in all cases is to block voltage-dependent calcium channels.[4] In cardiac pharmacology, calcium channel blockers are considered class-IV antiarrhythmic agents. Since calcium channels are especially concentrated in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, these agents can be used to decrease impulse conduction through the AV node, thus protecting the ventricles from atrial tachyarrhythmias. Specific conditions that fall under the definition of atrial tachyarrhythmias are atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, and so on.[34][35][36]

Verapamil is also a Kv voltage gated potassium channel blocker.[37]

Calcium channels are also present in the smooth muscle lining blood vessels. By relaxing the tone of this smooth muscle, calcium channel blockers dilate the blood vessels. This has led to their use in treating high blood pressure and angina pectoris. The pain of angina is caused by a deficit in oxygen supply to the heart.

Calcium channel blockers like verapamil dilate the coronary blood vessels, which increases the supply of blood and oxygen to the heart. They also cause dilatation of systemic peripheral vessels as well, causing a reduction in the workload of the heart. Thereby reducing myocardial oxygen consumption.[4]

Cluster headaches

[edit]Preventive therapy with verapamil is believed to work because it has an effect on the circadian rhythm and on CGRPs, as CGRP-release is controlled by voltage-gated calcium channels.[38]

Pharmacokinetic details

[edit]More than 90% of verapamil is absorbed when given orally,[4] but due to high first-pass metabolism, bioavailability is much lower (10–35%). It is 90% bound to plasma proteins and has a volume of distribution of 3–5 L/kg. It takes 1 to 2 hours to reach peak plasma concentration after oral administration.[4] It is metabolized in the liver to at least 12 inactive metabolites (though one metabolite, norverapamil, retains 20% of the vasodilatory activity of the parent drug). As its metabolites, 70% is excreted in the urine and 16% in feces; 3–4% is excreted unchanged in urine. This is a nonlinear dependence between plasma concentration and dosage. Onset of action is 1 to 2 hours after oral dosage, and 3 to 5 minutes after intravenous bolus dosage.[6][7] Biphasic or triphasic following IV administration; terminal elimination half-life is 2–8 hours.[39] Plasma half-life of 2–8 or 4.5–12 hours after single oral dose or multiple oral doses, respectively.[medical citation needed] It is not cleared by hemodialysis.[medical citation needed] It is excreted in human milk.[medical citation needed] Because of the potential for adverse reaction in nursing infants, nursing should be discontinued while verapamil is administered.[medical citation needed]

Veterinary use

[edit]Intra-abdominal adhesions are common in rabbits following surgery. Verapamil can be given postoperatively in rabbits which have suffered trauma to abdominal organs to prevent formation of these adhesions.[40][41][42] Such effect was not documented in another study with ponies.[43]

Uses in cell biology

[edit]Verapamil inhibits the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family of proteins found in stem cells and has been used to study cancer stem cells (CSC) within head and neck squamous cell carcinomas.[44]

Verapamil is also used in cell biology as an inhibitor of drug efflux pump proteins such as P-glycoprotein and other ABC transporter proteins.[45][44] This is useful, as many tumor cell lines overexpress drug efflux pumps, limiting the effectiveness of cytotoxic drugs or fluorescent tags. It is also used in fluorescent cell sorting for DNA content, as it blocks efflux of a variety of DNA-binding fluorophores such as Hoechst 33342. Radioactively labelled verapamil and positron emission tomography can be used with to measure P-glycoprotein function.[medical citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Verapamil". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Verapamil Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 18 November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 October 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Securon SR - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Calan- verapamil hydrochloride tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Human Medicines Evaluation Division (14 October 2020). "Active substance(s): verapamil" (PDF). List of nationally authorised medicinal products. European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Verapamil". Archived from the original on 30 October 2024.

Onset of Action[...]Oral: Immediate release: 1 to 2 hours (Singh 1978); IV bolus: 3 to 5 minutes

- ^ a b Singh BN, Ellrodt G, Peter CT (March 1978). "Verapamil: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use". Drugs. 15 (3): 169–197. doi:10.2165/00003495-197815030-00001. PMID 346345.

- ^ Schroeder JS, Frishman WH, Parker JD, et al. (2013). "Pharmacologic Options for Treatment of Ischemic Disease". Cardiovascular Therapeutics: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. Elsevier. pp. 83–130. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-0101-8.00007-2. ISBN 978-1-4557-0101-8.

The elimination half-life of standard verapamil tablets is usually 3 to 7 hours,...

- ^ a b c d e f "Verapamil Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Tfelt-Hansen PC, Jensen RH (July 2012). "Management of cluster headache". CNS Drugs. 26 (7): 571–580. doi:10.2165/11632850-000000000-00000. PMID 22650381. S2CID 22522914.

- ^ Merison K, Jacobs H (November 2016). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Childhood Migraine". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 18 (11): 48. doi:10.1007/s11940-016-0431-4. PMID 27704257. S2CID 28302667.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ "Isoptin: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 30 October 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Verapamil Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b Koda-Kimble and Young's Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs (10th ed.). USA: LWW. 2012. pp. 497, 1349. ISBN 978-1609137137.

- ^ Fahie S, Cassagnol M (2023). "Verapamil". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30860730. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Srinivasan V, Sivaramakrishnan H, Karthikeyan B (2011). "Detection, isolation and characterization of principal synthetic route indicative impurities in verapamil hydrochloride". Scientia Pharmaceutica. 79 (3): 555–568. doi:10.3797/scipharm.1101-19. PMC 3163365. PMID 21886903.

- ^ James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–520. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

- ^ Beck E, Sieber WJ, Trejo R (February 2005). "Management of cluster headache". American Family Physician. 71 (4): 717–724. PMID 15742909. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Jun P, Ko NU, English JD, et al. (November 2010). "Endovascular treatment of medically refractory cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 31 (10): 1911–1916. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2183. PMC 4067264. PMID 20616179.

- ^ Drislane F, Benatar M, Chang BS, et al. (1 January 2009). Blueprints Neurology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7817-9685-9. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Young JR, Sternbach S, Willinger M, et al. (17 December 2018). "The etiology, evaluation, and management of plantar fibromatosis". Orthopedic Research and Reviews. 11: 1–7. doi:10.2147/ORR.S154289. PMC 6367723. PMID 30774465.

- ^ a b Dutta D, Nagendra L, Raizada N, et al. (May–June 2023). "Verapamil improves One-Year C-Peptide Levels in Recent Onset Type-1 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis". Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 27 (3): 192–200. doi:10.4103/ijem.ijem_122_23. PMC 10424102. PMID 37583402.

- ^ Giannini AJ, Houser WL, Loiselle RH, et al. (December 1984). "Antimanic effects of verapamil". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 141 (12): 1602–1603. doi:10.1176/ajp.141.12.1602. PMID 6439057.

- ^ Giannini AJ, Taraszewski R, Loiselle RH (December 1987). "Verapamil and lithium in maintenance therapy of manic patients". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (12): 980–982. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb05600.x. PMID 3325531. S2CID 34536914.

- ^ Giannini AJ, Nakoneczie AM, Melemis SM, et al. (February 2000). "Magnesium oxide augmentation of verapamil maintenance therapy in mania". Psychiatry Research. 93 (1): 83–87. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(99)00116-X. PMID 10699232. S2CID 18216795.

- ^ "Securon 2.5 mg/ml IV Intravenous Injection - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Krevsky B, Maurer AH, Niewiarowski T, et al. (June 1992). "Effect of verapamil on human intestinal transit". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 37 (6): 919–924. doi:10.1007/BF01300391. PMID 1587197. S2CID 1007332.

- ^ Steele RM, Schuna AA, Schreiber RT (April 1994). "Calcium antagonist-induced gingival hyperplasia". Annals of Internal Medicine. 120 (8): 663–664. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-120-8-199404150-00006. PMID 8135450. S2CID 41746099.

- ^ Wilimowska J, Piekoszewski W, Krzyanowska-Kierepka E, et al. (2006). "Monitoring of verapamil enantiomers concentration in overdose". Clinical Toxicology. 44 (2): 169–171. doi:10.1080/15563650500514541. PMID 16615674. S2CID 10351499.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, California: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1637–39.

- ^ Ahmad F, Abu Sneineh M, Patel RS, et al. (June 2021). "In The Line of Treatment: A Systematic Review of Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia". Cureus. 13 (6): e15502. doi:10.7759/cureus.15502. PMC 8261787. PMID 34268033.

- ^ Delaney B, Loy J, Kelly AM (June 2011). "The relative efficacy of adenosine versus verapamil for the treatment of stable paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in adults: a meta-analysis". Eur J Emerg Med. 18 (3): 148–52. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283400ba2. PMID 20926952.

- ^ Soohoo MM, Stone ML, von Alvensleben J, et al. (2021). "Management of Atrial Tachyarrhythmias in Adults with Single Ventricle Heart Disease". Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics. 7 (4): 187–202. doi:10.1007/s40746-021-00231-w.

- ^ Wang SP, Wang JA, Luo RH, et al. (September 2008). "Potassium channel currents in rat mesenchymal stem cells and their possible roles in cell proliferation". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 35 (9): 1077–1084. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04964.x. PMID 18505444. S2CID 205457755.

- ^ Petersen AS, Barloese MC, Snoer A, et al. (September 2019). "Verapamil and Cluster Headache: Still a Mystery. A Narrative Review of Efficacy, Mechanisms and Perspectives". Headache. 59 (8): 1198–1211. doi:10.1111/head.13603. PMID 31339562. S2CID 198193843.

- ^ "Verapamil Hydrochloride: AHFS 24:28.92". ASHP Injectable Drug Information: 1563–1568. 1 January 2021. doi:10.37573/9781585286850.396. ISBN 978-1-58528-685-0. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ Elferink JG, Deierkauf M (January 1984). "The effect of verapamil and other calcium antagonists on chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes". Biochemical Pharmacology. 33 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90367-8. PMID 6704142.

- ^ Azzarone B, Krief P, Soria J, et al. (December 1985). "Modulation of fibroblast-induced clot retraction by calcium channel blocking drugs and the monoclonal antibody ALB6". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 125 (3): 420–426. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041250309. PMID 3864783. S2CID 10911875.

- ^ Steinleitner A, Lambert H, Kazensky C, et al. (January 1990). "Reduction of primary postoperative adhesion formation under calcium channel blockade in the rabbit". The Journal of Surgical Research. 48 (1): 42–45. doi:10.1016/0022-4804(90)90143-P. PMID 2296179.

- ^ Baxter GM, Jackman BR, Eades SC, et al. (1993). "Failure of calcium channel blockade to prevent intra-abdominal adhesions in ponies". Veterinary Surgery. 22 (6): 496–500. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950X.1993.tb00427.x. PMID 8116206.

- ^ a b Song J, Chang I, Chen Z, et al. (July 2010). "Characterization of side populations in HNSCC: highly invasive, chemoresistant and abnormal Wnt signaling". PLOS ONE. 5 (7): e11456. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511456S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011456. PMC 2897893. PMID 20625515.

- ^ Bellamy WT (1996). "P-glycoproteins and multidrug resistance". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 36: 161–183. doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.001113. PMID 8725386.