V for Vendetta (film)

| V for Vendetta | |

|---|---|

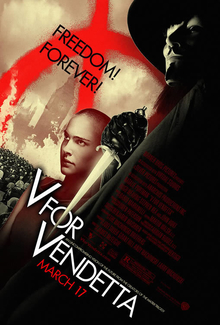

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James McTeigue |

| Screenplay by | The Wachowskis[a] |

| Based on | V for Vendetta by David Lloyd[b] |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Adrian Biddle |

| Edited by | Martin Walsh |

| Music by | Dario Marianelli |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 133 minutes[2] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50–54 million[4][5] |

| Box office | $134.7 million[4] |

V for Vendetta is a 2005 dystopian political action film directed by James McTeigue (in his feature directorial debut) from a screenplay by the Wachowskis.[a] It is based on the 1988–89 DC Vertigo Comics limited series of the same title by Alan Moore, David Lloyd, and Tony Weare. The film, set in a future where a fascist totalitarian regime has subjugated the UK, centres on V (portrayed by Hugo Weaving), an anarchist and masked freedom fighter who attempts to ignite a revolution through elaborate terrorist acts, and on Evey Hammond (portrayed by Natalie Portman), a young woman caught up in V's mission. Stephen Rea portrays a detective leading a desperate quest to stop V.

Produced by Silver Pictures, Virtual Studios and Anarchos Productions, Inc., V for Vendetta was originally scheduled for release by Warner Bros. Pictures on 4 November 2005 (a day before the 400th Guy Fawkes Night), but was delayed; it instead opened in the United States on 17 March 2006, to mostly positive reviews from critics and became a box office success, grossing $134 million against a production budget between $50–54 million. Alan Moore, dissatisfied with the film adaptations of his other works, From Hell (2001) and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), declined to watch the film and asked to not be credited or paid royalties.

Some political groups have seen V for Vendetta as an allegory of oppression by government; anarchists have used it to promote their beliefs. The film is credited for popularizing the use of the Guy Fawkes mask by anti-establishment political groups and activities; David Lloyd stated: "The Guy Fawkes mask has now become a common brand and a convenient placard to use in protest against tyranny—and I'm happy with people using it, it seems quite unique, an icon of popular culture being used this way."[6]

Plot

[edit]In the near future, Britain is ruled by the ultranationalist Norsefire political party, a fascist and totalitarian regime led by High Chancellor Adam Sutler, which controls the populace through propaganda and imprisons or executes those deemed undesirable, including immigrants, homosexuals, and people of alternative religions.

Evey Hammond is the daughter of parents who became activists after her brother perished in the St. Mary's school terrorist attack fourteen years earlier; they were detained and later died in prison when she was 12 years old. One evening, a Guy Fawkes masked vigilante, "V", rescues her from assault by the British secret police, known as The Fingermen, and brings her to witness his destruction of the Old Bailey via bombs. The following morning, on 5 November, V hijacks the state-run television network BTN to address the nation, claiming credit for the attack and encouraging the populace to resist Norsefire by joining him outside the Houses of Parliament on Guy Fawkes Night in one year's time. Evey is knocked unconscious while aiding V's escape, and he takes her with him to avoid her arrest and likely execution.

V kills Norsefire chief propagandist Lewis Prothero, coroner Dr. Delia Surridge, and, with Evey's assistance, Anthony Lilliman, the Bishop of London, pedophile and corrupt priest from Larkhill, whom V gets to by using Evey. Evey flees after betraying V, hoping to be forgiven by Norsefire. Assigned to capture V, Chief Inspector Eric Finch uses Surridge's journal and information from former covert operative William Rookwood (V in disguise), discovering that, two decades earlier, Surridge led biological weapons research and human experimentation at the Larkhill Detention Facility on behalf of then-Undersecretary of Defense Adam Sutler, creating the "St Mary's Virus". Although dozens of political prisoners died during experimentation, an amnesiac in cell "V" developed mutated immunities and disfigurements as well as physical enhancements and eventually destroyed Larkhill during his escape. Peter Creedy, head of the secret police, faked a terrorist attack by releasing the virus at targets including St. Mary's and used the resulting public fear to embed Norsefire in power. Simultaneously, the company manufacturing the cure enriched leading party members such as Prothero and Lilliman.

Evey takes shelter with her former boss, talkshow host Gordon Dietrich, who shows her his collection of illegal materials such as subversive paintings, an antique Quran, and homoerotic photographs. Emboldened by Evey and V, he satirizes Sutler on his show, leading to his and Evey's arrest and his eventual execution. She takes solace in a note hidden in her cell written by Valerie Page, a woman imprisoned in the cell next to V's, detailing her hopes despite her impending death. Tortured and facing her own execution, Evey refuses to submit to her captors and is released, finding herself in V's lair. V had intercepted Evey before Creedy's men and subjected her to false imprisonment (and gaslighting) so she could learn to live without fear. Although initially angry at V, Evey realizes that he has been avenging Valerie and the other Larkhill victims and promises to return to see him before 5 November. To kill the otherwise unreachable High Chancellor, V convinces Creedy to betray Sutler and replace him in exchange for V's surrender.

As 5 November approaches, V has hundreds of thousands of Guy Fawkes masks distributed across the nation, leading to a rise in masked, anonymous chaos and eventually riots after the secret police kill a young masked girl. V shares a dance with Evey before leading her to the shuttered London underground he restored over the previous decade. Not intending to survive the night, V bequeaths the decision to start the explosive-filled train to Evey. Although she pleads that he abandon his crusade and leave with her, he refuses. Creedy meets V and executes Sutler before demanding V unmask. Despite being shot and heavily injured, V kills Creedy and his men, stating that the idea he represents is more important than his identity. V returns to Evey, dying in her arms after admitting he loves her, and Finch finds her placing V's body aboard the train but, having become disillusioned with Norsefire, allows her to start it after she affirms that the people need hope. With Sutler and Creedy dead, the military forces in London stand down as countless citizens dressed as V descend on Parliament and witness its destruction. Finch asks for V's true identity, to which Evey replies, "He was all of us."

Cast

[edit]- Hugo Weaving as V, a masked, charismatic and skilled anarchist terrorist who had been the unwilling subject of experimentation by Norsefire. James Purefoy originally portrayed the character, but left six weeks into filming. He remained uncredited, with Weaving replacing him on set and redubbing Purefoy's scenes.[7]

- Natalie Portman as Evey Hammond, an employee of the state-run British Television Network who is rescued by V from a gang of London's secret police and subsequently becomes involved in his life.

- Stephen Rea as Chief Inspector Eric Finch of New Scotland Yard and Minister of Investigations (the "Nose"), the lead investigator in the V investigation, who uncovers an unspeakable government crime. When asked whether the politics attracted him to the film, Rea replied "Well, I don't think it would be very interesting if it was just comic book stuff. The politics of it are what gives it its dimension and momentum, and of course I was interested in the politics. Why wouldn't I be?"[8]

- Stephen Fry as Gordon Deitrich, a closeted gay talk show host. When asked in an interview what he liked about the role, Fry replied "Being beaten up! I hadn't been beaten up in a movie before and I was very excited by the idea of being clubbed to death."[9]

- John Hurt as Adam Sutler, the former Conservative Member of Parliament and Under-Secretary for Defence. High Chancellor Sutler is the founder of Norsefire and is Britain's authoritarian elected leader. Hurt also portrays two "Fake Sutler" actors lampooning him in an episode of Gordon Deitrich's talk show.[10][11]

- Tim Pigott-Smith as Peter Creedy, Norsefire's Party leader and the head of Britain's secret police (the "Finger").[12]

- Rupert Graves as Dominic Stone, Chief Inspector Finch's sergeant.

- Roger Allam as Lewis Prothero, the "Voice of London", a propagandist for Norsefire, and formerly the commander of Larkhill Detention Centre.

- Ben Miles as Roger Dascombe, the head of the government's propaganda division (the "Mouth") and chief executive of the British Television Network.

- Sinéad Cusack as Dr. Delia Surridge, the former head physician at the Larkhill Detention Centre, now a coroner.

- Natasha Wightman as Valerie Page, a lesbian imprisoned for her sexuality.

- Imogen Poots as Young Valerie Page

- John Standing as Anthony Lilliman, a corrupt bishop at Westminster Abbey and the former priest at Larkhill Detention Centre.

- Eddie Marsan as Brian Etheridge, the head of the government's audio surveillance division (the "Ear").

- Clive Ashborn as Guy Fawkes, the historical figure involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

- Guy Henry as Conrad Heyer, the head of the government's visual surveillance division (the "Eye").

Themes and interpretations

[edit]V for Vendetta sets the Gunpowder Plot as V's historical inspiration, contributing to his choice of timing, language, and appearance.[12] For example, the names Rookwood, Percy and Keyes are used in the film, which are also the names of three of the Gunpowder conspirators. The film creates parallels to Alexandre Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo, by drawing direct comparisons between V and Edmond Dantès. (In both stories, the hero escapes an unjust and traumatic imprisonment and spends decades preparing to take vengeance on his oppressors under a new persona.)[13][14][15] The film is also explicit in portraying V as the embodiment of an idea rather than an individual through V's dialogue and by depicting him without a past, identity or face. According to the official website, "V's use of the Guy Fawkes mask and persona functions as both practical and symbolic elements of the story. He wears the mask to hide his physical scars, and in obscuring his identity – he becomes the idea itself."[12]

As noted by several critics and commentators, the film's story and style mirror elements from Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera.[16][17] V and the Phantom both wear masks to hide their disfigurements, control others through the leverage of their imaginations, have tragic pasts, and are motivated by revenge. V and Evey's relationship also parallels many of the romantic elements of The Phantom of the Opera, where the masked Phantom takes Christine Daaé to his subterranean lair to re-educate her.[16][17][18]

As a film about the struggle between freedom and the state, V for Vendetta takes imagery from many classic totalitarian icons both real and fictional, including the Third Reich and George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.[12][10] For example, Adam Sutler[10] primarily appears on large video screens and on portraits in people's homes, both common features among modern totalitarian regimes and reminiscent of the image of Big Brother. There is also the state's use of mass surveillance, such as closed-circuit television, on its citizens – reminiscent of the comprehensive mass surveillance systems currently deployed in many nations, such as China or the United Kingdom. The name Adam Sutler is intentionally similar to Adolf Hitler. Both are given to hysterical speech; Sutler is also a racial purist, although Jews have been replaced by Asians and Muslims as the focus of Norsefire ethnoreligious propaganda and persecution. Valerie was sent to a detention facility for her lesbianism and then had medical experiments performed on her,[19] reminiscent of the persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.[17]

We felt the novel was very prescient to how the political climate is at the moment. It really showed what can happen when society is ruled by government, rather than the government being run as a voice of the people. I don't think it's such a big leap to say that things like that can happen when leaders stop listening to the people.

The filmmakers added topical references relevant to a 2006 audience. According to the Los Angeles Times, "With a wealth of new, real life parallels to draw from in the areas of government surveillance, torture, fear mongering and media manipulation, not to mention corporate corruption and religious hypocrisy, you can't really blame the filmmakers for having a field day referencing current events." There are also references to an avian flu pandemic,[20] as well as pervasive use of biometric identification and signal intelligence gathering and analysis by the regime.

Film critics, political commentators and other members of the media have also noted the film's numerous references to events surrounding the George W. Bush administration in the United States. These include the hoods and sacks worn by the prisoners in Larkhill that have been seen as a reference to the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse.[21][22] The Homeland Security Advisory System and rendition are also referenced.[23] One of the forbidden items in Gordon's secret basement is a protest poster with a mixed US–UK flag with a swastika and the title "Coalition of the Willing, To Power" which combines the "Coalition of the Willing" with Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of will to power.[24]

Despite the America-specific references, the filmmakers have always referred to the film as adding dialogue to a set of issues much broader than the US administration.[10] When James McTeigue was asked whether or not BTN was based on Fox News Channel, McTeigue replied, "Yes. But not just Fox. Everyone is complicit in this kind of stuff. It could just as well been the Britain's Sky News Channel, also a part of News Corp."[10]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The film was made by many of the same filmmakers involved in The Matrix series. In 1988, producer Joel Silver acquired the rights to two of Alan Moore's works: V for Vendetta and Watchmen.[25] After the release and relative success of Road House, writer Hilary Henkin was brought on to flesh out the project with an initial draft – one that bears little, if any, relation to the finished product, with the inclusion of overtly satirical and surrealistic elements not present in the graphic novel, as well as the removal of much of the novel's ambiguity, especially in regard to V's identity.[26] The Wachowskis were fans of V for Vendetta and in the mid-1990s, before working on The Matrix, wrote a draft screenplay that closely followed the graphic novel. During the post-production of the second and third The Matrix films, they revisited the screenplay and offered the director's role to James McTeigue. All three were intrigued by the original story's themes and found them to be relevant to the contemporary political landscape. Upon revisiting the screenplay, the Wachowskis set about making revisions to condense and modernise the story, while at the same time attempting to preserve its integrity and themes. James McTeigue cites the film The Battle of Algiers as his principal influence in preparing to film V for Vendetta.[12]

Moore explicitly disassociated himself from the film due to his lack of involvement in its writing or directing, as well as due to a continuing series of disputes over film adaptations of his work.[27] He ended cooperation with his publisher, DC Comics, after its corporate parent, Warner Bros., failed to retract statements about Moore's supposed endorsement of the film. Moore said that the script contained plot holes[28] and that it ran contrary to the theme of his original work, which was to place two political extremes (fascism and anarchism) against one another. He argues his work had been recast as a story about "current American neoconservatism vs. current American liberalism".[29] Per his wishes, Moore's name does not appear in the film's closing credits. Co-creator and illustrator David Lloyd supports the film adaptation, commenting that the script is very good but that Moore would only ever be truly happy with a complete book-to-screen adaptation.[25] In 2021, Lloyd revealed that Moore had wanted to make V for Vendetta into a movie around the time the comic book was originally being conceived.[30]

Casting

[edit]James Purefoy was originally cast as V, but dropped out after six weeks into filming. Although at the time it was reported this was because of difficulties wearing the mask for the entire film,[7] he later stated that it was really due to creative differences on how V should be portrayed.[31] He was replaced by Hugo Weaving, who had previously worked with Joel Silver and the Wachowskis on The Matrix series.

Director James McTeigue first met Natalie Portman during the filming of Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, on which he worked as assistant director. In preparation for the role, Portman worked with dialect coach Barbara Berkery to speak in an English accent, studied films such as The Weather Underground, and read the autobiography of Menachem Begin.[12] She received top billing for the film. Her role in the film has parallels to her role in Léon: The Professional.[27] According to Portman: "the relationship between V and Evey has a complication [like] the relationship in that film. There's moments when it's father/daughter. There's moments when it's like lovers, it has moments when it's mentor/student. And many times [those are] all at once."[32]

Filming

[edit]V for Vendetta was filmed in London, England, and in Potsdam, Germany, at Babelsberg Studios. Much of the film was shot on sound stages and indoor sets, with location work done in Berlin for three scenes: the Norsefire rally flashback, Larkhill, and Bishop Lilliman's bedroom. The scenes that took place in the abandoned London Underground were filmed at the disused Aldwych tube station. Filming began in early March 2004 and lasted through early June 2004.[25] V for Vendetta is the final film shot by cinematographer Adrian Biddle, who died of a heart attack on 7 December 2005, 9 months after the movie's world debut.[33]

To film the final scene at Westminster, the area from Trafalgar Square and Whitehall up to Parliament and Big Ben had to be closed for three nights from midnight until 5 am. This was the first time the security-sensitive area (home to 10 Downing Street and the Ministry of Defence) had ever been closed to accommodate filming.[34] Then-Prime Minister Tony Blair's son, Euan, worked on the film's production and is said (according to an interview with Stephen Fry) to have helped the filmmakers obtain the unparalleled filming access. This drew criticism of Blair from MP David Davis due to the film's content. However, the filmmakers denied Euan Blair's involvement in the deal,[35] stating that access was acquired through nine months of negotiations with 14 different government departments and agencies.[34]

Post-production

[edit]The film was designed to have a retrofuturistic look, with heavy use of grey tones to give a dreary, stagnant feel to totalitarian London. The largest set created for the film was the Shadow Gallery, which was made to feel like a cross between a crypt and an undercroft.[36]

One of the major challenges in the film was how to bring V to life from under an expressionless mask. Thus, considerable effort was made to bring together lighting, acting, and Weaving's voice to create the proper mood for the situation. Since the mask muffled Weaving's voice, his entire dialogue was re-recorded in post-production.[34]

Music and soundtrack

[edit]The V for Vendetta soundtrack was released by Astralwerks Records on 21 March 2006.[37] The original scores from the film's composer, Dario Marianelli, make up most of the tracks on the album.[38] The soundtrack also features three vocals played during the film: "Cry Me a River" by Julie London, a cover of The Velvet Underground song "I Found a Reason" by Cat Power and "Bird Gerhl" by Antony and the Johnsons.[38] As mentioned in the film, these songs are samples of the 872 blacklisted tracks on V's Wurlitzer jukebox that V "reclaimed" from the Ministry of Objectionable Materials. The climax of Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture appears at the end of the track "Knives and Bullets (and Cannons too)". The Overture's finale is played at key parts at the beginning and end of the film.

Three songs were played during the ending credits which were not included on the V for Vendetta soundtrack.[38] The first was "Street Fighting Man" by the Rolling Stones. The second was a special version of Ethan Stoller's "BKAB". In keeping with revolutionary tone of the film, excerpts from "On Black Power" (also in "A Declaration of Independence") by black nationalist leader Malcolm X, and from "Address to the Women of America" by feminist writer Gloria Steinem were added to the song. Gloria Steinem can be heard saying: "This is no simple reform ... It really is a revolution. Sex and race, because they are easy and visible differences, have been the primary ways of organising human beings into superior and inferior groups and into the cheap labour on which this system still depends." The final song was "Out of Sight" by Spiritualized.

Also in the film were segments from two of Antonio Carlos Jobim's classic bossa nova songs, "The Girl From Ipanema" and "Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars". These songs were played during the "breakfast scenes" with V and Deitrich and were one of the ways used to tie the two characters together. Beethoven's Symphony No.5 also plays an important role in the film, with the first four notes of the first movement signifying the letter "V" in Morse code.[39][40] Gordon Deitrich's Benny Hill-styled comedy sketch of Chancellor Sutler includes the "Yakety Sax" theme. Inspector Finch's alarm clock begins the morning of 4 November with the song "Long Black Train" by Richard Hawley, which contains the foreshadowing lyrics "Ride the long black train ... take me home black train."

Differences between the film and the graphic novel

[edit]The film's story was adapted from Alan Moore and David Lloyd's graphic novel V for Vendetta; this was originally published between 1982 and 1985 in the British comic anthology Warrior, and then reprinted and completed by DC. Moore's comics were later compiled into a graphic novel and published again in the United States under DC's Vertigo imprint and in the United Kingdom under Titan Books.[41]

There are several fundamental differences between the film and the original source material. Alan Moore's original story was created as a response to British Thatcherism in the early 1980s and was set as a conflict between a fascist state and anarchism, while the film's story was changed by the Wachowskis to fit a modern US political context. Alan Moore, however, charged that, in doing so, the story turned into an American-centric conflict between liberalism and neoconservatism, and abandoned the original anarchist–fascist themes. Moore states that "[t]here wasn't a mention of anarchy as far as I could see. The fascism had been completely defanged. I mean, I think that any references to racial purity had been excised, whereas actually, fascists are quite big on racial purity." Furthermore, in the original story, Moore attempted to maintain moral ambiguity, and not to portray the fascists as caricatures, but as realistic, rounded characters. The time limitations of a film meant that the story had to omit or streamline some of the characters, details, and plotlines from the original story.[12]

Many of the characters from the graphic novel underwent significant changes for the film. V is characterised in the film as a romantic freedom fighter who shows concern over the loss of innocent life.[42] However, in the graphic novel, he is portrayed as ruthless, willing to kill anyone who gets in his way. Evey Hammond's transformation as V's protégée is also much more drastic in the novel than in the film. Gordon, a very minor character in both versions, is also drastically changed. In the novel, Gordon is a small-time criminal who takes Evey into his home after V abandons her on the street. The two share a brief romance before Gordon is killed by a Scottish gang. In the film, however, Gordon is a well-mannered colleague of Evey's, and is later revealed to be gay. He is arrested by Fingermen for broadcasting a political parody on his TV program, and is later executed when a Quran is found in his possession.[27]

Release

[edit]

The film adopts extensive imagery from the 1605 Gunpowder Plot, in which a group of Catholic conspirators plotted to destroy the Houses of Parliament in order to spark a revolution in Great Britain.[25] The film was originally scheduled for release on the weekend of 5 November 2005, the Plot's 400th anniversary, with the tag line "Remember, remember the 5th of November", taken from a traditional British rhyme memorialising the event. However, the marketing angle lost much of its value when the release date was pushed back to 17 March 2006. Many have speculated that the delay was caused by the London tube bombing on the 7 July and the failed 21 July bombing.[43] The filmmakers have denied this, saying that the delays were due to the need for more time to finish the visual effects production.[44] V for Vendetta had its first major premiere on 11 December 2005, at Butt-Numb-A-Thon, followed by a premiere on 13 February 2006 at the Berlin Film Festival.[45][10] It opened for general release on 17 March 2006 in 3,365 cinemas in the United States, the United Kingdom and six other countries.[4]

Marketing

[edit]Promotion

[edit]The cast and filmmakers attended several press conferences that allowed them to address issues surrounding the film, including its authenticity, Alan Moore's reaction to it and its intended political message. The film was intended to be a departure from some of Moore's original themes. In the words of Hugo Weaving: "Alan Moore was writing about something which happened some time ago. It was a response to living in Thatcherite Britain ... This is a response to the world in which we live today. So I think that the film and the graphic novel are two separate entities." Regarding the film's controversial political content, the filmmakers have said that the film is intended more to raise questions and add to a dialogue already present in society, rather than provide answers or tell viewers what to think.[10]

Books

[edit]The original graphic novel by Moore and Lloyd was re-released as a hardback collection in October 2005 to tie into the film's original release date of 5 November 2005.[46] The film renewed interest in Alan Moore's original story, and sales of the original graphic novel rose dramatically in the United States.[47]

A novelisation of the film, written by Steve Moore (no relation to Alan Moore) and based on the Wachowskis' script, was published by Pocket Star on 31 January 2006.[48] Spencer Lamm, who has worked with the Wachowskis, created a "behind-the-scenes" book. Titled V for Vendetta: From Script to Film, it was published by Universe on 22 August 2006.[49]

Home media

[edit]V for Vendetta was released on DVD in the US on 1 August 2006,[50] in three formats: a single-disc widescreen version, a single-disc fullscreen version, and a two-disc wide-screen special edition.[51] The single disc versions contain a short (15:56) behind-the-scenes featurette titled "Freedom! Forever![52] Making V for Vendetta" and the film's theatrical trailer, whereas the two-disc special edition contains three additional documentaries, and several extra features for collectors. On the second disc of the special edition, a short Easter egg clip of Natalie Portman on Saturday Night Live can be viewed by selecting the picture of wings on the second page of the menu.

Its Blu-ray edition was a top seller in the United States in late May 2008.[53] It was released on 4K Ultra HD Blu-Ray in October 2020.[54]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]By December 2006, V for Vendetta had grossed $134,686,457, of which $70,511,035 was from the United States. The film led the U.S. box office on its opening day, taking in an estimated $8,742,504, and remained the number one film for the remainder of the weekend, taking in an estimated $25,642,340. Its closest rival, Failure to Launch, took in $15,604,892.[4] The film debuted at number one in the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden and Taiwan. V for Vendetta also opened in 56 IMAX cinemas in North America, grossing $1.36 million during the opening three days.[55]

DVD sales were successful, selling 1,412,865 DVD units in the first week of release which translated to $27,683,818 in revenue. By the end of 2006, 3,086,073 DVD units had been sold, bringing in slightly more than its production cost with $58,342,597.[56] As of September 2018, the film has grossed over $62 million from DVD and Blu-ray sales in the United States.[57]

The film was also successful in terms of merchandise sales, with hundreds of thousands of Guy Fawkes masks from the film having been sold every year since the film's release, as of 2011.[58] Time Warner owns the rights to the image and is paid a fee with the sale of each official mask.[59][60]

Critical response

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 73% approval rating based on 258 reviews, with an average rating of 6.80/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Visually stunning and thought-provoking, V For Vendetta's political pronouncements may rile some, but its story and impressive set pieces will nevertheless entertain."[61] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 62 out of 100 based on 39 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[62] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[63]

Ebert and Roeper gave the film a "two thumbs up" rating. Roger Ebert stated that V for Vendetta "almost always has something going on that is actually interesting, inviting us to decode the character and plot and apply the message where we will".[16] Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton from At the Movies stated that despite the problem of never seeing Weaving's face, there was good acting and an interesting plot, adding that the film is also disturbing, with scenes reminiscent of Nazi Germany.[64]

Jonathan Ross from the BBC blasted the film, calling it a "woeful, depressing failure" and stating that the "cast of notable and familiar talents such as John Hurt and Stephen Rea stand little chance amid the wreckage of the Wachowski siblings' dismal script and its particularly poor dialogue."[65] Sean Burns of Philadelphia Weekly gave the film a 'D', criticising the film's treatment of its political message as being "fairly dim, adolescent stuff,"[66] as well as expressing dislike for the "barely decorated sets with television-standard overlit shadow-free cinematography by the late Adrian Biddle. The film is a visual insult."[66] On Alan Moore removing his name from the project, Burns says "it's not hard to see why,"[66] as well as criticising Portman's performance: "Portman still seems to believe that standing around with your mouth hanging open constitutes a performance."[66]

Harry Guerin from the Irish TV network RTÉ states the film "works as a political thriller, adventure and social commentary and it deserves to be seen by audiences who would otherwise avoid any/all of the three". He added that the film will become "a cult favourite whose reputation will only be enhanced with age."[67] Andy Jacobs for the BBC gave the film two stars out of five, remarking that it is "a bit of a mess ... it rarely thrills or engages as a story."[68]

V was included on Fandomania's list of The 100 Greatest Fictional Characters.[69] Empire magazine named the film the 418th greatest movie of all time in 2008.[70]

Accolades

[edit]V for Vendetta received a few awards, although at the 2007 Saturn Awards Natalie Portman won the Best Actress award.[71] The film was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form in 2007.[72]

Political response

[edit]V for Vendetta deals with issues of totalitarianism, homosexuality, Islamophobia and terrorism. Its controversial story line and themes have been the target of both criticism and praise from sociopolitical groups.

On 17 April 2006, the New York Metro Alliance of Anarchists organised a protest against DC Comics and Time Warner, accusing it of watering down the story's original message in favour of violence and special effects.[73][74] David Graeber, an anarchist scholar and former professor at Yale University, was not upset by the film. "I thought the message of anarchy got out in spite of Hollywood." However, Graeber went on to state: "Anarchy is about creating communities and democratic decision making. That's what is absent from Hollywood's interpretation."[73]

Film critic Richard Roeper dismissed Christian criticism of the film on the television show Ebert and Roeper, saying that V's "terrorist" label is applied in the film "by someone who's essentially Hitler, a dictator."[75]

LGBT commentators have praised the film for its positive depiction of gay people. Sarah Warn of AfterEllen called the film "one of the most pro-gay ever". Warn went on to praise the central role of the character Valerie "not just because it is beautifully acted and well written, but because it is so utterly unexpected [in a Hollywood film]."[19]

David Walsh of the World Socialist Web Site criticised V's actions as "antidemocratic," calling the film an example of "the bankruptcy of anarcho-terrorist ideology;" Walsh writes that because the people have not played any part in the revolution, they will be unable to produce a "new, liberated society."[76]

The film was broadcast on China's national TV station, China Central Television (CCTV) on 16 December 2012 completely uncensored,[77] surprising many viewers. While many believed that the government had banned the film, the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television stated that it was not aware of a ban; CCTV makes its own decisions on whether to censor foreign films. Liu Shanying, a political scientist at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences who used to work for CCTV, speculated that the showing indicated that Chinese film censorship is getting loosened.[78]

See also

[edit]- List of fictional prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- List of films featuring surveillance

- List of films that depict class struggle

- Anonymous

- Mr. Robot

- Propaganda of the deed

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "V for Vendetta". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ "V FOR VENDETTA (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 16 March 2006. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "| Berlinale | Archive | Annual Archives | 2006 | Programme – V For Vendetta | V wie Vendetta". Berlinale.de. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d "V for Vendetta (2006)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2005.

- ^ "V for Vendetta (2005)". The Numbers. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Waites, Rosie (20 October 2011). "V for Vendetta masks: Who's behind them?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b "James Purefoy Quit 'V for Vendetta' Because He Hated Wearing the Mask". starpulse.com. 24 February 2006. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- ^ Byrne, Paul. "The Rea Thing". eventguide. InterArt Media. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ Utichi, Joe (20 March 2006). "Exclusive Interview with Stephen Fry — V for Vendetta". Filmfocus. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "V for Vendetta Press Footage". Warner Bros. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- ^ Jacobsen, Kurt. "V for Vendetta – Graphic Enough?". logosjournal.com. Logos Journal. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Production Notes for V for Vendetta". official webpage. vforvendetta.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2006.

- ^ Andersen, Neil. "V for Vendetta". CHUM.mediaeducation.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ Suprynowicz, Vin (2 April 2006). "VIN SUPRYNOWICZ: I wanted to like 'V for Vendetta'". BoxOfficeCritic.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ Peterman, Eileen (9 April 2006). "V for Vendetta (R)". BoxOfficeCritic.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger (16 March 2006). "'Dystopia' with a capital V". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Stein, Ruthe (16 March 2006). "In 'Vendetta,' disastrous U.S. and British policymaking gives rise to terrorism – what a shocker". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2006.

- ^ Travers, Peter. "V for Vendetta". rollingstones.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ a b Warn, Sarah (20 March 2006). "V for Vendetta: A Brave, Bold Film for Gays and Lesbians". AfterEllen. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2006.

- ^ Chocano, Carina (17 March 2006). "V for Vendetta". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2006.

- ^ "Gunpowder, treason and plot". The Age. Melbourne: Fairfax Digital. 19 March 2006. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2006.

- ^ David Denby (12 March 2006). "BLOWUP: V for Vendetta". The New Yorker. Conde Nast. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2006.

- ^ Breimeier, Russ (16 March 2006). "V for Vendetta". Christianitytoday.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2006.

- ^ Lamm, Spencer (August 2006). V for Vendetta: from Script to Film. Universe. p. 241. ISBN 0-7893-1520-3.

- ^ a b c d "V for Vendetta news". vforvendetta.com. Warner Brothers. Archived from the original on 15 March 2006. Retrieved 31 March 2006.

- ^ "V for Vendetta: the Henkin Script". Shadow galaxy. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Goldstein, Hilary (17 March 2006). "V for Vendetta: Comic vs. Film". IGN. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (23 May 2005). "Moore Slams V For Vendetta Movie, Pulls LoEG From DC Comics". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 3 January 2006.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi (15 March 2006). "A FOR ALAN, Pt. 1: The Alan Moore interview". GIANT Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 March 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ HeroJournalism (27 May 2021). "Artist David Lloyd on V for Vendetta, the Movie & Disagreeing with Alan Moore". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Pevens, Lane (5 December 2020). "The Truth About James Purefoy's Decision To Quit 'V For Vendetta'". Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Murray, Rebecca. "Natalie Portman and Joel Silver Talk About "V for Vendetta"". About.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ Guard, Howard Adrian Biddle obituary Archived 28 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, www.guardian.co.uk, 18 January 2006. Retrieved 10 June 2012

- ^ a b c "V for Vendetta — About the production". Official website. Archived from the original on 15 March 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ "How E got the V in Vendetta". The Guardian. London. 23 March 2006. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ Warner Bros (2006). V for Vendetta Unmasked (TV-Special). United States: Warner Bros.

- ^ "Detailed V For Vendetta Soundtrack Music Information". CD Universe. Muze Inc. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Tillnes, John. "Soundtrack Review: V for Vendetta by Dario Marianelli (2006)". Soundtrack Geek. Soundtrackgeek.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Moore, Alan; David Lloyd (November 2005). V for Vendetta. Vertigo. ISBN 1-4012-0792-8.

Inspector Finch recognises the background noise as Beethoven's Fifth, and states: "It's Morse code for the letter "V""

- ^ "Newswatch 1940s". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ Itzcoff, Dave (12 March 2006). "The Vendetta Behind 'V for Vendetta". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "V for Vendetta the Page Vs. The Screen". Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ Edelman, Scott. "C is for controversy". scifi.com. SCI FI. Archived from the original on 1 January 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ Reardanz, Karen (23 August 2005). "Natalie Portman's 'V for Vendetta' Postponed". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ Matt Dentler (11 December 2005). "B for Butt-Numb-A-Thon". IndieWire. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ ASIN 1401207928, V for Vendetta [Hardcover] ISBN 978-1-4012-0792-2

- ^ "V for Vendetta graphic novel is a US Bestseller". televisionpoint.com. 31 March 2006. Archived from the original on 19 November 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2006.

- ^ ASIN 1416516999, V for Vendetta: a Novelization ISBN 978-1416516996

- ^ ASIN 0789315203, V for Vendetta: From Script to Film [Hardcover] ISBN 978-0-7893-1520-5

- ^ "V for Vendetta (2006)". rottentomatoes.com. Flixster, Inc. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "V for Vendetta (Widescreen Edition)". warnerbros.com Inc. Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ ASIN B000FS9FCG, V for Vendetta (Widescreen Edition) (2006)

- ^ "Top Blu-ray Titles". Video Business. Vol. 28, no. 22. 2 June 2008. p. 36. ISSN 0279-571X. Gale A179621338.

- ^ Fallon, Sean (11 September 2020). "V for Vendetta Hits 4K Blu-ray With an Exclusive Gift Set and SteelBook". ComicBook.com. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill (21 March 2006). "V for Vendetta Posts Strong IMAX Opening". vfxworld.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2006.

- ^ "V for Vendetta – DVD Sales". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ "V for Vendetta (2006) – Video Sales". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ "Story and Symbol: V for Vendetta and OWS". Psychology Today. 4 November 2011. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Carbone, Nick (29 August 2011). "How Time Warner Profits from the 'Anonymous' Hackers". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Bilton, Nick (28 August 2011). "Masked Protesters Aid Time Warner's Bottom Line". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ "V for Vendetta (2006)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "V for Vendetta (2006)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (9 February 2015). "'SpongeBob' Counts $55.4M Treasure; 'Jupiter' Down, 'Son' Up In Monday B.O. Actuals". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "V for Vendetta". atthemovies.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

- ^ Ross, Jonathan. "Jonathan on ... V for Vendetta". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

- ^ a b c d Burns, Sean (15 March 2006). "V for Vendetta". Philadelphia Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ Guerin, Harry (15 March 2006). "V for Vendetta". rte.ie. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

- ^ Jacobs, Andy (17 March 2006). "BBC Films: V For Vendetta". BBC News. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Fictional Characters". Fandomania.com. 21 September 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Empire's the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ David S. Cohen (10 May 2007). "'Superman' tops Saturns". Variety. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "V for Vendetta: Award Wins and Nominations". IMDb. 2006. Archived from the original on 25 July 2024. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ a b Launder, William (2 May 2006). ""V" stands for very bad anarchist movie". Columbia News Service. Archived from the original on 13 March 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ Inducer, Smile (28 September 2006). "V for Vendetta? A for Anarchy!". NYMAA. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- ^ "Rotten Tomatoes: Ebert & Roeper: "V for Vendetta" Dark, Thoughtful, And That's Good". Rotten Tomatoes. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ Patranobis, Sutirtho (16 December 2012). "China shocked after 'v for vendetta' aired on national tv". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ Watt, Louise (20 December 2012). "'V For Vendetta' Airs In China, Stunning TV Viewers". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Amazon, Nancy (21 March 2017). "v for vendetta". Kissing Fingertips.

- Asher-Perrin, Emmet (14 June 2016). "Apologize to No One — V for Vendetta is More Important Today Than it Ever Was". Tor.com.

- Clough, Rob (14 October 2021). "The Untold Truth of V for Vendetta". Looper.

- Crow, David (5 November 2019). "The Creeping Reality of V for Vendetta". Den of Geek.

- Patel, Varun (30 May 2020). "V for Vendetta Ending, Explained". The Cinemaholic.

- Riedel, Samantha (9 November 2018). "How V for Vendetta Predicted America's Descent Into Fascism". Them.

- Rudoy, Matthew (4 July 2020). "V For Vendetta: 10 Most Memorable Quotes". Comic Book Resources.

- Barry, Barry (20 June 2020). "V For Vendetta: Movie vs Graphic Novel". This Is Barry.

- Wickman, Forrest (9 December 2011). "Is the Guy Fawkes Mask a Metaphor for the Closet?". Slate.

- Billias, Nancy, ed. (2011). "Sympathy for the Devil: The Hero is a Terrorist in V for Vendetta (Margarita Carretero-González)". Promoting and Producing Evil. Rodopi. pp. 199–210. doi:10.1163/9789042029408_012. ISBN 978-9042029392.

- Evans, Jonathan C.; Giddens, Thomas, eds. (2013). "V for Valerie: Lesbianism in V for Vendetta (Derek Frasure)". Cultural Excavation and Formal Expression in the Graphic Novel. Inter-Disciplinary Press. pp. 161–172. doi:10.1163/9781848881990_017. ISBN 978-1848881990.

- Foy, Joseph J., ed. (2008). "R for Revolution: Hobbes and Locke on Social Contracts and Scarlet Carsons (Dean A. Kowalski)". Homer Simpson Goes to Washington: American Politics through Popular Culture. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 19–40. ISBN 978-0813125121.

- Lamm, Spencer, ed. (2006). V for Vendetta: from Script to Film. Universe Publishing. ISBN 978-0789315205.

External links

[edit]- V for Vendetta – Official website at Warner Bros.

- V for Vendetta at IMDb

- V for Vendetta at the TCM Movie Database

- V for Vendetta at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- V for Vendetta at Box Office Mojo

- V for Vendetta at Rotten Tomatoes

- V for Vendetta at Metacritic

- V for Vendetta script at the Internet Movie Script Database

- 2005 films

- V for Vendetta

- 2005 action thriller films

- 2005 directorial debut films

- 2000s political thriller films

- 2000s superhero films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- American science fiction action films

- Anarchist fiction

- British LGBTQ-related films

- British nonlinear narrative films

- German nonlinear narrative films

- English-language German films

- Fiction about government

- Lesbian-related films

- Live-action films based on comics

- Films about anti-fascism

- Films about fascism

- Films about totalitarianism

- Films about freedom of expression

- Films set in the 2010s

- Films set in the 2020s

- Films set in the 2030s

- Films set in London

- Films shot in Berlin

- Films shot in London

- Films based on Vertigo Comics titles

- Films based on works by Alan Moore

- Films directed by James McTeigue

- Films critical of religion

- Films produced by Grant Hill (producer)

- Films produced by Joel Silver

- Films produced by The Wachowskis

- Films with screenplays by The Wachowskis

- Films scored by Dario Marianelli

- Cultural depictions of Metropolitan Police officers

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- IMAX films

- Silver Pictures films

- Babelsberg Studio films

- Warner Bros. films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s British films

- 2000s German films

- Catholic Church in popular culture

- British dystopian films

- Dystopian films

- 2005 LGBTQ-related films

- English-language action thriller films

- Saturn Award–winning films