User:Zimmster3/sandbox

| |

| Long title | An act to enforce constitutional rights, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 86th United States Congress |

| Effective | May 6, 1960 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | P.L. 86–449 |

| Statutes at Large | 74 Stat. 89 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Civil Rights Act of 1957 |

| Titles amended | 18, 42 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Civil Rights Act of 1964 Civil Rights Act of 1991 | |

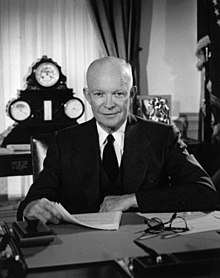

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 (Pub. L. 86–449, 74 Stat. 89, enacted May 6, 1960) was a United States federal law that established federal inspection of local voter registration rolls and introduced penalties for anyone who obstructed someone's attempt to register to vote or to vote. It was designed to deal with discriminatory laws and practices in the segregated South, by which blacks had been effectively disfranchised since the late nineteenth and turn of the twentieth century. It extended the life of the Civil Rights Commission, previously limited to two years, to oversee registration and voting practices. The act was signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and served to eliminate certain loopholes left by the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Origins

[edit]By the late 1950s, the civil rights movement had been pressuring Congress to push through civil rights legislation for the expansion and protection of the rights of African-Americans. The first major piece of civil rights legislation passed by Congress was the Civil Rights Act of 1957. The act, while enforcing the voting rights of African-Americans set out in the Fifteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution, had several loopholes that allowed for the continued denial of rights. The legislation was proposed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his message to the 86th Congress on February 5, 1959, where he stated "that every individual regardless of his race, religion, or national origin is entitled to the equal protection of the laws."

Eisenhower's mandate

[edit]

Toward the end of his presidency, President Eisenhower visibly supported civil rights legislation. In his message to Congress, he proposed seven recommendations for the pursuit and protection of civil rights:

- Strengthen the laws that would root out threats to obstruct court orders in school desegregation cases

- Provide more investigative authority to the FBI in crimes involving the destruction of schools/churches

- Grant Attorney General power to investigate Federal election records

- Provide temporary program for aid to agencies to assist changes necessary for school desegregation decisions

- Authorize provision of education for children of Armed Forces

- Consider establishing a statutory Commission on Equal Job Opportunity Under Government Contracts (later mandated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to create the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission)

- Extend Civil Rights Commission an additional 2 years[1]

Committee & Passage in the House of Representatives

[edit]The bill began in the House of Representatives where it existed under jurisdiction of the House Judiciary Committee. The chairman of the committee, Congressman Emmanuel Celler, was known to be a firm supporter of the civil rights movement. The bill was easily approved by the Judiciary Committee but the Rules Committee attacked the Judiciary Committee to prevent the bill coming to the floor of the House.[2] The bill was introduced to the House on March 10, 1960. The "voter referees" plan was part of a House amendment to the original bill to substitute Representative Robert Kastenmeier's "enrollment officers" plan. After several amendments, the House of Representatives approved the bill on March 24, 1960 by a vote of 311-109.[3]

Passage in the Senate

[edit]The Senate's Judiciary Committee also faced attempts to dislodge the bill. Southern Democrats had long acted as a voting block to resist or reject legislation to enforce constitutional rights in the South and made it difficult for proponents of civil rights to add strengthening amendments.[4] After amendments in the Senate, H.R. 8601 was approved by the Senate on April 8, 1960 by a vote of 71-18. [5]

The House of Representatives approved the Senate amendments on April 21, 1960 by a vote of 288-295 and the bill was signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on May 6, 1960.

Content of the Act

[edit]Title I

[edit]Title I amended Chapter 17 of title 18 of the United States Code, 18 U.S.C. § 1509, outlawed obstruction of court orders. If convicted, one could be fined no more than $1,000 and/or imprisoned for no more than one year.

Title II

[edit]Title II outlawed fleeing a state for damaging or destroying a building or property, illegal possession or use of explosives, and threats or false threats to damage property using fire or explosives.

Section 201 amended Chapter 49 of title 18 (18 U.S.C. § 1074). The amendment outlaws interstate or international movement to avoid prosecution for damaging or destroying any building or structure. The section also outlaws flight to avoid testimony in a case relating to such an offense. If convicted, one could be fined no more than $5,000 and/or imprisoned for no more than five years.

Section 203 amended Chapter 39 of title 18 (18 U.S.C. § 837). The amendment dealt with the illegal use or possession of explosives. The section outlaws transportation or possession of any explosive with intent to damage a building or property. The section also makes the conveying of false information or threats to damage or destroy any building or property illegal.

Title III

[edit]Title III focused on federal election records.

Section 301 calls for the preservation of all election records and papers which come into an officer or custodian's possession relating to poll tax or other act regarding voting in an election (except Puerto Rico). If an officer fails to comply, he/she could be fined no more than $1,000 and/or imprisoned for no more than one year. Section 302 declares that any person that intentionally alters, damages, or destroys a record shall be fined no more than $1,000 and/or imprisoned for no more than one year. Section 304 establishes that no person shall disclose any election record. Section 306 defines the term "officer of election".

Title IV

[edit]Title IV extended the powers of the Civil Rights Commission.

Section 401 of Title IV amended Section 105 of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 (71 Stat. 635) declaring that "each member of the Commission shall have the power and authority to administer oaths or take statements of witnesses under affirmation." [6]

Title V

[edit]Title V arranged for the provision of free education for children of members of armed forces.

Title VI

[edit]Title VI amended section 131 of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 (71 Stat. 637) to address the issue of depriving African-Americans the right to vote.

Section 601 declares that those given the legal right to vote shall not be deprived of that right on account of race or color. Any person denying that right shall "constitute contempt of court." [7] The section also states that the courts can appoint "voting referees" to report the court findings based on literacy tests. The section also defines the world "vote" as the entire process of making a vote effective--registration, casting a ballot, and having that ballot counted. [8]

Title VII

[edit]Title VII established the separability of the act, affirming that the rest of the act shall go unaffected if one provision is found invalid.

Subsequent History

[edit]After the subsequent intensive acts of 1964 and 1965, the act of 1957 and the Civil Rights Act of 1960 were deemed ineffective for the firm establishment of civil rights. The latter legislation had firmer ground for the enforcement and protection of a variety of civil rights, where the acts of 1957 and 1960 were largely limited to voting rights.[9] The Civil Rights Act of 1960 dealt with race and color but omitted rights regarding those discriminated for national origin even though Eisenhower had called for it in his message to Congress.[10]

See also

[edit]- Civil Rights Movement

- Civil rights

- Civil Rights Act of 1866

- Civil Rights Act of 1871

- Civil Rights Act of 1875

- Civil Rights Act of 1957

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Civil Rights Act of 1968

- Equal Pay Act of 1963

- Force Act of 1870

- Force Act of 1871

- Voting Rights Act

- Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Lodge Bill

- Martin Luther King Jr.

- Malcolm X

- Reconstruction Acts

- Affirmative action in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Schwartz, Bernard ed. (1970). Statutory History of the United States. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 933–1013.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Berman, Daniel M. (1966). A Bill Becomes Law: Congress Enacts Civil Rights Legislation. London: The MacMillan Company.

- ^ Schwartz, Bernard ed. (1970). Statutory History of the United States. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 933–1013.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Berman, Daniel M. (1966). A Bill Becomes Law: Congress Enacts Civil Rights Legislation. London: The MacMillan Company.

- ^ Schwartz, Bernard ed. (1970). Statutory History of the United States. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 933–1013.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "Civil Rights Act of 1960".

- ^ "Civil Rights Act of 1960".

- ^ "Before the Voting Rights Act". Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ Bardolph, Richard (1970). The Civil Rights Record: Black Americans and the Law, 1849-1970. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, Inc. pp. 311, 352–3, 395, 403–5, 493, 495. ISBN 0-690-19448-X.

- ^ Perea, Juan F. "Ethnicity and Prejudice: Reevaluating "National Origin" Discrimination Under Title VII". William and Mary Law Review.