User:Yoyoyao11/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Yoyoyao11. A user sandbox is a subpage of the user's user page. It serves as a testing spot and page development space for the user and is not an encyclopedia article. |

Twenty-sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution

[edit]The Twenty-sixth Amendment (Amendment XXVI) to the United States Constitution established a nationally standardized minimum age of 18 for participation in state and federal elections. It was proposed by Congress on March 23, 1971, and three-fourths of the states ratified it by July 1, 1971.

Various public officials had supported lowering the voting age during the mid-20th century, but were unable to gain the legislative momentum necessary for passing a constitutional amendment.

The drive to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 grew across the country during the 1960s and was driven in part by the military draft held during the Vietnam War. The draft conscripted young men at the ages of 18 into the United States Armed Forces, primarily the U.S. Army, to serve in or support military combat operations in Vietnam.[1] This means young men could be required to fight and possibly die for their nation in wartime at 18. However, these same citizens cannot have a legal say in the government's decision to wage that war until the age of 21. A youth rights movement emerged in response, calling for a similarly reduced voting age. A common slogan of proponents of lowering the voting age was "old enough to fight, old enough to vote".[2]

Determined to get around inaction on the issue, congressional allies included a provision for the 18-year-old vote in a 1970 bill that extended the Voting Rights Act. The Supreme Court subsequently held in the case of Oregon v. Mitchell that Congress lacked the authority to force states to establish a minimum voting age in elections at the state and local level. Recognizing the confusion and costs that would be involved in maintaining separate voting rolls and elections for federal and state contests, Congress quickly proposed and the states ratified the Twenty-sixth Amendment.

Background

[edit]The framers of the U.S. Constitution did not establish specific criteria for national citizenship or voting qualifications in state or federal elections. Before the Twenty-sixth Amendment, states had the authority to set their own minimum voting ages, which was typically twenty-one as the national standard.[3]

Senator Harley Kilgore began advocating for a lowered voting age in 1941 in the 77th Congress.[4] Calls for the minimum age to be lowered began after President Franklin D. Roosevelt expanded the military draft to include men as young as 18 during World War II. In 1942, West Virginia Congressman Jennings Randolph introduced the first federal bill to lower the voting age, arguing that young soldiers fighting in World War II should have the right to vote. Despite the support of fellow senators, representatives, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Randolph's 1942 bill failed to become law. However, public interest in lowering the voting age became a topic of interest at the local level. In 1943 and 1955 respectively, the Georgia and Kentucky legislatures approved measures to lower the voting age to 18.[5]

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in his 1954 State of the Union address, became the first president to publicly support prohibiting age-based denials of suffrage for those 18 and older.[6] During the 1960s, both Congress and the state legislatures came under increasing pressure to lower the minimum voting age from twenty-one to 18. The escalation of the conflict in Vietnam during the 1960s heightened the urgency of the issue. Students and youth activists demanded the vote, pointing to the huge numbers of young people drafted to fight in Southeast Asia. "Old enough to fight, old enough to vote" was a common slogan used by proponents of lowering the voting age. The slogan traced its roots to World War II, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt lowered the military draft age to 18.

In 1963, the President's Commission on Registration and Voting Participation, in its report to President Johnson, encouraged lowering the voting age. Johnson proposed an immediate national grant of the right to vote to 18-year-olds on May 29, 1968.[7] Historian Thomas H. Neale argues that the move to lower the voting age followed a historical pattern similar to other extensions of the franchise; with the escalation of the war in Vietnam, constituents were mobilized and eventually a constitutional amendment passed.[8]

Those advocating for a lower voting age drew on a range of arguments to promote their cause, and scholarship increasingly links the rise of support for a lower voting age to young people's role in the civil rights movement and other movements for social and political change of the 1950s and 1960s.[9][10] Increasing high-school graduation rates and young people's access to political information through new technologies also influenced more positive views of their preparation for the most important right of citizenship.[9]

Between 1942, when public debates about a lower voting age began in earnest, and the early 1970s, ideas about youth agency increasingly challenged the caretaking model that had previously dominated the nation's approaches to young people's rights.[9] Characteristics traditionally associated with youth—idealism, lack of "vested interests," and openness to new ideas—came to be seen as positive qualities for a political system that seemed to be in crisis.[9]

In 1970, Senator Ted Kennedy proposed amending the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to lower the voting age nationally.[11] On June 22, 1970, President Richard Nixon signed an extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that required the voting age to be 18 in all federal, state, and local elections.[12] In his statement on signing the extension, Nixon said:

Despite my misgivings about the constitutionality of this one provision, I have signed the bill. I have directed the Attorney General to cooperate fully in expediting a swift court test of the constitutionality of the 18-year-old provision.[13]

Subsequently, Oregon and Texas challenged the law in court, and the case came before the Supreme Court in 1970 as Oregon v. Mitchell.[14] By this time, four states had a minimum voting age below 21: Georgia, Kentucky, Alaska and Hawaii.[15][16]

Oregon v. Mitchell

[edit]During debate of the 1970 extension of the Voting Rights Act, Senator Ted Kennedy argued that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment allowed Congress to pass national legislation lowering the voting age.[17] In Katzenbach v. Morgan (1966), the Supreme Court had ruled that if Congress acts to enforce the 14th Amendment by passing a law declaring that a type of state law discriminates against a certain class of persons, the Supreme Court will let the law stand if the justices can "perceive a basis" for Congress's actions.[18]

President Nixon disagreed with Kennedy in a letter to the Speaker of the House and the House minority and majority leaders, asserting that the issue is not whether the voting age should be lowered, but how. In his own interpretation of Katzenbach, Nixon argued that to include age as something discriminatory would be too big of a stretch and voiced concerns that the damage of a Supreme Court decision to overturn the Voting Rights Act could be disastrous.[19]

In Oregon v. Mitchell (1970), the Supreme Court considered whether the voting-age provisions Congress added to the Voting Rights Act in 1970 were constitutional. The court ruled that Congress lacked the authority to force states to establish a minimum voting age in elections at the state and local level. However, the Court upheld the provision establishing the voting age as 18 in federal elections. The Court was deeply divided in this case, and a majority of justices did not agree on a rationale for the holding.[20][21] Justice Hugo Black wrote in the court's majority opinion that a constitutional amendment was necessary to enact this change.

The decision left Americans between 18 and 21 years old in an awkward spot. They had the right to vote for president but not necessarily for their local or state leaders. This led to states keeping the voting age at 21 for their elections but having to set up separate voter rolls so that those aged 18 to 21 could vote in federal elections.[22]

Opposition

[edit]Although the Twenty-sixth Amendment passed faster than any other constitutional amendment, about 17 states refused to pass measures to lower their minimum voting ages after Nixon signed the 1970 extension to the Voting Rights Act.[23] Opponents to extending the vote to youths questioned the maturity and responsibility of people at the age of 18. Representative Emanuel Celler, one of the most vocal opponents of a lower voting age from the 1940s through 1970 (and Chair of the powerful House Judiciary Committee for much of that period), insisted that youth lacked "the good judgment" essential to good citizenship and that the qualities that made youth good soldiers did not also make them good voters.[24] Professor William G. Carleton wondered why the vote was proposed for youth at a time when the period of adolescence had grown so substantially rather than in the past when people had more responsibilities at earlier ages.[25] Carleton further criticized the move to lower the voting age citing American preoccupations with youth in general, exaggerated reliance on higher education, and equating technological savvy with responsibility and intelligence.[26] He denounced the military service argument as well, calling it a "cliche".[27] Considering the ages of soldiers in the Civil War, he asserted that literacy and education were not the grounds for limiting voting; rather, common sense and the capacity to understand the political system grounded voting age restrictions.[28]

James J. Kilpatrick, a political columnist, asserted that the states were "extorted" into ratifying the Twenty-sixth Amendment.[29] In his article, he claims that by passing the 1970 extension to the Voting Rights Act, Congress effectively forced the States to ratify the amendment lest they be forced to financially and bureaucratically cope with maintaining two voting registers. George Gallup also mentions the cost of registration in his article showing percentages favoring or opposing the amendment, and he draws particular attention to the lower rates of support among adults aged 30–49 and over 50 (57% and 52% respectively) as opposed to those aged 18–20 and 21–29 (84% and 73% respectively).[30]

Proposal and ratification

[edit]

Passage by Congress

[edit]Senator Birch Bayh's subcommittee on constitutional amendments initiated hearings to extend voting rights to 18-year-olds in 1968.[31]

After Oregon v. Mitchell, Bayh surveyed election officials in 47 states and found that registering an estimated 10 million young people in a separate system for federal elections would cost approximately $20 million.[32] Bayh concluded that most states could not change their state constitutions in time for the 1972 election, mandating national action to avoid "chaos and confusion" at the polls.[33]

On March 2, 1971, Bayh's subcommittee and the House Judiciary Committee approved the proposed constitutional amendment to lower the voting age to 18 for all elections.[34]

On March 10, 1971, the Senate voted 94–0 in favor of proposing a constitutional amendment to guarantee the minimum voting age could not be higher than 18.[35][36] On March 23, 1971, the House of Representatives voted 401–19 in favor of the proposed amendment.[37][38]

Ratification by the states

[edit]Having been passed by the 92nd United States Congress, the proposed Twenty-sixth Amendment was sent to the state legislatures for their consideration. Ratification was completed on July 1, 1971, after the amendment had been ratified by thirty-eight states:[39]

- Connecticut: March 23, 1971

- Delaware: March 23, 1971

- Minnesota: March 23, 1971

- Tennessee: March 23, 1971

- Washington: March 23, 1971

- Hawaii: March 24, 1971

- Massachusetts: March 24, 1971

- Montana: March 29, 1971

- Arkansas: March 30, 1971

- Idaho: March 30, 1971

- Iowa: March 30, 1971

- Nebraska: April 2, 1971

- New Jersey: April 3, 1971

- Kansas: April 7, 1971

- Michigan: April 7, 1971

- Alaska: April 8, 1971

- Maryland: April 8, 1971

- Indiana: April 8, 1971

- Maine: April 9, 1971

- Vermont: April 16, 1971

- Louisiana: April 17, 1971

- California: April 19, 1971

- Colorado: April 27, 1971

- Pennsylvania: April 27, 1971

- Texas: April 27, 1971

- South Carolina: April 28, 1971

- West Virginia: April 28, 1971

- New Hampshire: May 13, 1971

- Arizona: May 14, 1971

- Rhode Island: May 27, 1971

- New York: June 2, 1971

- Oregon: June 4, 1971

- Missouri: June 14, 1971

- Wisconsin: June 22, 1971

- Illinois: June 29, 1971

- Alabama: June 30, 1971

- Ohio: June 30, 1971

- North Carolina: July 1, 1971

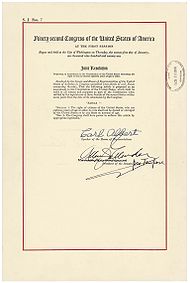

Having been ratified by three-fourths of the States (38), the Twenty-sixth Amendment became part of the Constitution. On July 5, 1971, the Administrator of General Services, Robert Kunzig, certified its adoption. President Nixon and Julianne Jones, Joseph W. Loyd Jr., and Paul S. Larimer of the "Young Americans in Concert" also signed the certificate as witnesses. During the signing ceremony, held in the East Room of the White House, Nixon talked about his confidence in the youth of America:

As I meet with this group today, I sense that we can have confidence that America's new voters, America's young generation, will provide what America needs as we approach our 200th birthday, not just strength and not just wealth but the 'Spirit of '76' a spirit of moral courage, a spirit of high idealism in which we believe in the American dream, but in which we realize that the American dream can never be fulfilled until every American has an equal chance to fulfill it in their own life.[40]

The amendment was subsequently ratified by five more states, bringing the total number of ratifying states to forty-three:[39]

- 39. Oklahoma: July 1, 1971

- 40. Virginia: July 8, 1971

- 41. Wyoming: July 8, 1971

- 42. Georgia: October 4, 1971

- 43. South Dakota: March 4, 2014[41]

No action has been taken on the amendment by the states of Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, or Utah.

- ^ "The 26th Amendment". History. November 27, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "The 26th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution". National Constitution Center – The 26th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- ^ Vaughn, Vanessa E. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS: Twenty-Sixth Amendment. Defining Documents: The 1970s. pp. 145–147.

- ^ Neale, Thomas H., "Lowering the Voting Age was not a New Idea", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 35.

- ^ Neale, Thomas H., "Lowering the Voting Age was not a New Idea", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 36–37.

- ^ Dwight D. Eisenhower, "Public Papers of the Presidents", January 7, 1954, p. 22.

- ^ University of California-Santa Barbara, The American Presidency Project, "Commencement Address at Texas Christian University".

- ^ Neale, Thomas H., "Lowering the Voting Age was not a New Idea", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 38.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ De_Schweinitz, Rebecca. (2009). If we could change the world: young people and America's long struggle for racial equality. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3235-6. OCLC 963537002.

- ^ Kennedy, Edward M. "The Time Has Come to Let Young People Vote", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 56-64.

- ^ University of California, Santa Barbara. "Statement on Signing the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970". presidency.ucsb.edu.

- ^ Richard Nixon, "Public Papers of the Presidents" June 22, 1970, p. 512.

- ^ Educational Broadcasting Corporation (2006). "Majority Rules: Oregon v. Mitchell (1970)". PBS.

- ^ 18 for Georgia and Kentucky, 19 for Alaska and 20 for Hawaii

- ^ Neale, Thomas H. The Eighteen Year Old Vote: The Twenty-Sixth Amendment and Subsequent Voting Rates of Newly Enfranchised Age Groups. 1983.

- ^ "Oregon v. Mitchell". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- ^ Graham, Fred P., in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 67.

- ^ Nixon, Richard, "Changing the Voting age will Require a Constitutional Amendment", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 70-77.

- ^ Tokaji, Daniel P. (2006). "Intent and Its Alternatives: Defending the New Voting Rights Act" (PDF). Alabama Law Review. 58: 353. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970), pp. 188–121

- ^ "Making Civics Real: Workshop 2: Essential Readings". Annenberg Learner. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Neale, Thomas H., "Lowering the Voting Age was not a New Idea", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 35.

- ^ de Schweinitz, Rebecca (2015-05-22), "The Proper Age for Suffrage", Age in America, NYU Press, pp. 209–236, doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479870011.003.0011, ISBN 978-1-4798-7001-1

- ^ Carleton, William G., "Teen Voting Would Accelerate Undesirable Changes in the Democratic Process", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 47.

- ^ Carleton, William G., "Teen Voting Would Accelerate Undesirable Changes in the Democratic Process", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 48-49.

- ^ Carleton, William G., "Teen Voting Would Accelerate Undesirable Changes in the Democratic Process", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 49.

- ^ Carleton, William G., "Teen Voting Would Accelerate Undesirable Changes in the Democratic Process", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 50-51.

- ^ Kilpatrick, James J., "The States are being Extorted into Ratifying the Twenty-sixth Amendment", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 123-127.

- ^ Gallup, George, "The Majority of Americans Favor the Twenty-sixth Amendment", in Amendment XXVI Lowering the Voting Age, ed. Engdahl, Sylvia (New York: Greenhaven Press, 2010), 128-130.

- ^ Graham, Fred P. (May 15, 1968). "Voting Age of 18 Is Supported By Four Senators at a Hearing". The New York Times. p. 23.

- ^ Sperling, Godfrey Jr. (February 13, 1971). "Bayh peers into dual-voting thicket: Fraud possibilities weighed 'Intolerable burden'". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ MacKenzie, John P. (February 13, 1971). "Bayh Favors Amendment To End Vote-at-18 'Chaos'". The Washington Post. pp. A2.

- ^ "Amendment on Vote at 18 Gains a Step". The Chicago Tribune. United Press International. March 3, 1971. pp. C1.

- ^ Senate, Journal of the Senate, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 1971. S. S.J. Res. 7

- ^ "House Gets 18-Vote After Senate OKs It". The Evening Press (Binghamton, New York). Associated Press. March 11, 1971. p. 12.

- ^ House, Journal of the House, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 1971. H. S.J. Res. 7

- ^ Milutin Tomanović, ed. (1972). Hronika međunarodnih događaja 1971 [The Chronicle of International Events in 1971] (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade: Institute of International Politics and Economics. p. 2608.

- ^ a b "The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation, Centennial Edition, Interim Edition: Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the United States to June 26, 2013" (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 2013. p. 44. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ "Remarks at a Ceremony Marking the Certification of the 26th Amendment to the Constitution". The American Presidency Project. University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Senate Joint Resolution 1". South Dakota Legislature. Pierre, South Dakota: SD Legislative Research Council. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.