User:Wijbrand/sandbox

Leiden University, History of the Modern Middle East, 2021-2022.

I am a student enrolled in the course above, whose assessment entails editing a Simple Wikipedia entry. I will be using the space below to draft this entry.

Wikipedia page to be edited: "Safavid Dynasty"

Origins

[edit]The Safavid Dynasty emerged from the mystical Sufi Order (Arabic: Tariqa) of the Safaviyya family in Ardabil (Azerbaijan Province of Iran) in 1501 C.E. As a family of Sayyids, claimed descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, they built their religious ideas on the beliefs of their ancestor Sheikh Safī al-Din (1252/3 – 1334). Sheikh Safī followed Zahed Gilani of the Zahidī Sufi order and after the passing of Gilani, Safī al-Din became leader and renamed the order to Safaviyya.[1] He implemented both Shi'i and Sunni dogmas into his conceptions of Islam[2], which attracted Sunnis as well as Shiites to the order.

Although the Safaviyya used to be Sunnis[2], successor Sheikh Joneyd, who had become head of the order in 1447, converted to Shi'ism in 1460. By doing so he initiated a significant turning point for the Sufi order, which did not go unnoticed and implicated a pre-announcement for a significant shift in the Islamic World. The Safaviyya received a clearer political identity by Sheikh Heydar (son of Joneyd), who transformed it into a military division, basing their insights on Islamic principles and practice.

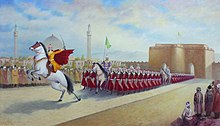

The supporting tribesmen of this military movement were called Qizilbāsh, named after their red colored headwear. The hats symbolized their loyalty to the twelve imams of the Shia and the acknowledgement of Heydar as their spiritual leader. However, the use of the hat is academically disputed and might also refer to Heydars grandfather, whose nickname was Zarrin Kolāh ("golden crown") or even go back to the first Shi'i imam, Ali b. Abi Taleb, who wore a similar hat during the conquest of Kheybar in 629 C.E.[3]

Marriages between the Turkmen Aqqoyunlu dynasty from Eastern Turkey and the Saffaviya established new ties, but soon they disbanded again, after which the two became enemies in their competition for power.[4] Subsequently Heydar was killed in a battle with the Aqqoyunlu[5], but his son Ismail survived and stayed hidden in Lahijan with the help of the Qizilbāsh clans. Soon after Shāh Ismail I founded the official Safavid Dynasty and forcibly made Twelver Shi'ism the official state religion of Iran.

History (Main part - already there)

[edit]Demise / Downfall

[edit]On October 23, 1722 C.E. after a siege of seven months, alongside the suffering of the populace due to famine and disease, the Safavid capital of Isfahan finally fell into the hands of the Afghan king Mahmud Hotak, marking the end of the Safavid Dynasty.[6] Author Rudi Matthee writes committedly about these events in the last chapter of Persia in Crisis, stating that attacks from Uzbeks and Afghans, drought, a virtually empty public treasury and hence a lack of funds to pay the soldiers were the death blow for the Safavids.[7]

Safavid Shahs of Iran

[edit]For an extended overview please consult the full Family Tree of the Safavid kings.

Architecture (part of 'Culture')

[edit]One of the most prominent constructions of the early Safavid Dynasty is most probably the Mausoleum of Sheikh Safī al-Din, shrine of the founder of the Safaviyya Sufi Order, in Ardabil (Northwest Iran), near the Caspian Sea. In The Safavid Dynastic Shrine, author Kishwar Rizvi explains that this building had a central function for the Safaviyya Sufis, who considered Ardabil their base. Part of the building was likely constructed during Safī al-Dins life, while a large cemetery as well as dwelling areas were added later. Rizvi bases her information on a land register and a biography written soon after the passing of the Sheikh.[8] She describes it as the Safaviyyas great sanctuary, a bustling social establishment for various public and private purposes. Inside, Sufi rituals such as the Sufra took place and there was a strict day itinerary. Moreover the shrine was used to give shelter to criminals and fugitives.[9]

Other series of buildings and complexes of the Safavid Dynasty can be found in the city of Isfahan, in Central Iran, which after Qazvin had become the new capital of Safavid Iran in 1598. Built under Shāh Abbās I, the Ali Qapū Palace, the Chehel Sotoun Pavillion and the Naghsh-e Jahān Square were the pinnacle of the Safavid Dynasty. Under Shāh Abbās I the city expanded rapidly on both sides of the Zayande Rud and especially in the old center, where the Meydan-e Naghsh-e Jahān and its surroundings became the quarter with the highest density of architectural highlights, functioning as an embellishment of the new Safavid capital.[10] According to various scholarly studies the exact start and completion dates of some of these buildings remain unclear until today.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ G. E. Browne, A Literary History of Persia, vol. 4, 33–4. ISBN 9788178981253

- ^ a b Baltacıoğlu-Brammer, Ayşe (2022). The emergence of the Safavids as a mystical order and their subsequent rise to power in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in: The Safavid World. Abingdon (UK): Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-138-94406-0.

- ^ Baltacıoğlu-Brammer, Ayşe (2022). The emergence of the Safavids as a mystical order and their subsequent rise to power in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in: The Safavid World. Abingdon (UK): Routledge. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-138-94406-0.

- ^ Woods, John E. (1999). The Aqquyunlu: Clan, Confederation, Empire. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-87480-565-1.

- ^ Matthee, Rudi (28 July 2008). "Safavid Dynasty". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press. p. 126. doi:10.2307/j.ctv19prrqm.8. ISBN 978-0-300-11254-2.

- ^ Matthee, Rudolph P. (2011). Persia in Crisis : Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 235–241. ISBN 978-0-85772-094-8. OCLC 793166622.

- ^ Rizvi, Kishwar (2011). The Safavid Dynastic Shrine: Architecture, Religion, and Power in Early Modern Iran. London: I.B.Tauris. p. 10. ISBN 9781848853546.

- ^ Rizvi, Kishwar (2011). The Safavid dynastic shrine : architecture, religion and power in early modern Iran. British Institute of Persian Studies. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 32–41. ISBN 978-1-84885-354-6. OCLC 716841717.

- ^ Melville, Charles (2016-11-14). "New Light on Shah ʿAbbas and the Construction of Isfahan". Muqarnas Online. 33 (1): 155. doi:10.1163/22118993_03301P007. ISSN 0732-2992.

- ^ Melville, Charles (2016-11-14). "New Light on Shah ʿAbbas and the Construction of Isfahan". Muqarnas Online. 33 (1): 159. doi:10.1163/22118993_03301P007. ISSN 0732-2992.

Bibliography

[edit]- Matthee, Rudolph P. The Safavid World. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021. ISBN 9781138944060

- Aldous, Gregory. Qizilbash Tribalism and Royal Authority in Early Safavid Iran, 1524-1534. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2013.

- Stierlin, Henri. Panorama van Oude Culturen: De Perzen. Pully (Switzerland), Agence Internationale d'Edition de Jean F. Gonthier, 1980. ISBN 9788854401464

- Savory, Roger M, Ahmet T. Karamustafa. “Esmāʿīl i Ṣafawī”, Encyclopædia Iranica, VIII/6, pp. 628-636. Accessed 9 May 2022. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/esmail-i-safawi

- Mitchell, Colin P. New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society. Vol. 8. London: Routledge, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203854631.

- Trausch, Tilmann. Representing Joint Rule as the Murshid-i Kāmil’s Will. The Medieval History Journal 19, no. 2 (2016): 285–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971945816665959.

- Quinn, Sholeh Alysia. Shah ʻAbbas : the King Who Refashioned Iran, 2015. ISBN 9781851684250

- Rizvi, Kishwar. The Safavid Dynastic Shrine: Architecture, Religion, and Power in early Modern Iran. London: I.B. Taurus, 2011. ISBN 9781848853546.

- Melville, Charles. New Light on Shah ʿAbbas and the Construction of Isfahan. Muqarnas 33, no. 1 (2016): 155–76. https://doi.org/10.1163/22118993_03301P007.

- Abbas Amanat. The Demise of the Safavid Order and the Unhappy Interregnums (1666–1797). In Iran, 126. Yale University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv19prrqm.8.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. Persia in crisis: Safavid decline and the fall of Isfahan. London: I.B.Tauris, 2012. ISBN 978-1-83860-707-4.

Further Reading

[edit]- Ghereghlou, Kioumars. Cashing in on Land and Privilege for the Welfare of the Shah: Monetisation of Tiyūl in early Safavid Iran and Eastern Anatolia, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 68, no. 1 (2015): 87–141. https://doi.org/10.1556/AOrient.68.2015.1.5.

- Newman, A.J, and University of Edinburgh Staff. Society and Culture in the Early Modern Middle East. Vol. 46. Leiden: BRILL, 2003. ISBN 9789004127746.

- Axworthy, Plassche, Westelaken, Ruud van de. Iran : een cultuurgeschiedenis. Amsterdam : Antwerpen: Bulaaq ; EPO, 2009.

- Trausch, Tilmann. Formen Höfischer Historiographie Im 16. Jahrhundert : Geschichtsschreibung Unter Den Frühen Safaviden: 1501-1578. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ÖAW), 2015. ISBN 9783700176664

- Meri, Josef W. Medieval Islamic Civilization : an Encyclopedia, Vol. 1: A-K: Index. New York, NY, [etc.]: Routledge, 2006. ISBN 9781138061330

- Mardaga, Pierre. Espace Persan: Architecture Traditionelle en Iran. VRBI (Belgium), 1986. ISBN 2-87009-249-0.

- Emami, Farshid. Royal Assemblies and Imperial Libraries: Polygonal Pavilions and Their Functions in Mughal and Safavid Architecture. South Asian Studies, 35:1, 63-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2019.1605564

- Emami, Farshid. Coffeehouses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of a Public Sphere in Safavid Isfahan. Muqarnas, 2016. 33(1), 177–220. https://doi.org/10.1163/22118993_03301P008