User:Tpwissaa/sandbox

POLTICS OF TH SU

Tea Party Movement | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ideology | Fiscal conservatism Economic liberalism Libertarianism Right-wing populism |

| Political position | Right-wing |

| National affiliation | Republican Party |

| |

New Deal Coalition | |

|---|---|

| Prominent members | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman Lyndon B. Johnson Adlai Stevenson II Henry A. Wallace Hugh S. Johnson |

| Founded | 1932 |

| Dissolved | 1960's |

| Succeeded by | Progressive Party Dixiecrats |

| Ideology | Early phase: Big tent Populism Social liberalism Later phase: Modern liberalism Anti-communism Pro-Civil rights |

| Slogan | "Happy Days Are Here Again" (1932) |

New Deal Coalition | |

|---|---|

| Prominent members | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson Adlai Stevenson II Henry A. Wallace Hugh S. Johnson |

| Founded | 1932 |

| Dissolved | 1960's |

| Ideology | Modern liberalism Social liberalism Populism Progressivism |

| Political position | Centre-left to Left wing |

| Slogan | "Happy Days Are Here Again" |

| Senate Seats (75th Congress) | 76 / 96 |

| House Seats (75th Congress) | 333 / 435 |

The United States of America | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1781–1789 | |||||||

| Motto: E pluribus unum | |||||||

| Anthem: None official | |||||||

Map of the United States in 1783 | |||||||

| Capital | Philadelphia (1781-1783) Princeton (1783) Annapolis (1783-1784) Trenton (1784) New York City (1784-1789) | ||||||

| Government | Confederal republic | ||||||

| President of the Congress | |||||||

• 1779-1781 | Samuel Huntington (first) | ||||||

• 1788 | Cyrus Griffin (last) | ||||||

| Legislature | Congress of the Confederation | ||||||

| Historical era | American Revolution | ||||||

• Established | 1 March 1781 | ||||||

| September 1781 | |||||||

| June 1783 | |||||||

• Signing of the Treaty of Paris | September 1783 | ||||||

• Constitutional Convention begins | May 1787 | ||||||

| August 1787 | |||||||

• States begin ratification of Constitution | December 1787 | ||||||

• Articles of Confederation superseded by 1789 Constitution | 4 March 1789 | ||||||

| |||||||

United Colonies of New England | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1643–1686 | |||||||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||||||

New England in 1660 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Disestablished | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English Massachusett, Mi'kmaq | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Congregationalism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Directorial confederation | ||||||||||||||

| Commissioners | |||||||||||||||

• 1643 | Thomas Dudley John Winthrop William Collier Edward Winslow Theophilus Eaton Thomas Gregson George Fenwick Edward Hopkins | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | None (deffered to individual colonial assemblies) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Great Migration, British colonization of the Americas, American Indian Wars, Anglo-Dutch Wars | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 19 May 1643 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1686 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Cold War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NATO and Warsaw Pact states during the Cold War-era | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Communist Bloc 1947-1961

| |||||||

Reformers | |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1620s |

| Dissolved | 1790s |

| Ideology | Reformism Liberalism Republicanism Modernization Populism Merchant's interests |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| Religion | Protestanism |

Conservatives | |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1690s |

| Dissolved | 1790s |

| Succeeded by | Federalist Party |

| Ideology | Theocracy Isolationism Conservatism New Jerusalem Regionalism Anti-catholicism Autonomism |

| Political position | Right wing |

| Religion | Puritanism |

| |

Loyalists | |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | United Empire Loyalists |

| Ideology | Monarchism Conservatism Toryism Anti-Independence |

| Political position | Right wing |

| Religion | Protestant |

| |

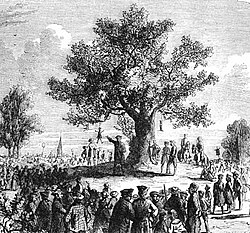

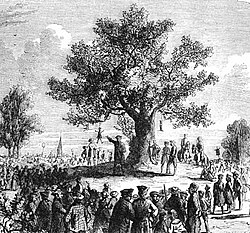

Sons of Liberty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1765 |

| Dissolved | 1776 |

| Preceded by | Loyal Nine |

| Succeeded by | Provincial Committees of safety Committees of correspondence |

| Ideology | Initial phase: Rights of Englishmen "No taxation without representation" Later phase: Liberalism Republicanism American Independence |

| Political position | Left wing |

| National affiliation | Whiggism |

| Regional affiliation | Patriot revolutionaries |

| Colors | Red White |

| Slogan | "No taxation without representation" |

Sons of Liberty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1765 |

| Dissolved | 1776 |

| Preceded by | Loyal Nine |

| Succeeded by | Provincial Committees of safety Committees of correspondence |

| Ideology | Initial phase: Rights of Englishmen "No taxation without representation" Later phase: Liberalism Republicanism American Independence |

| Political position | Left wing |

| Colors | Red, White |

| Sons of Liberty | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

| Leaders | See below |

| Foundation | 1765 |

| Dissolved | 1776 |

| Motives | Before 1766: Opposition to the Stamp Act After 1766: Independence of the United Colonies from Great Britain |

| Active regions | Province of Massachusetts Bay Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Province of New Hampshire Province of New Jersey Province of New York Province of Maryland Province of Virginia |

| Major actions | Public demonstrations, Direct action, Destruction of Crown goods and property, Boycotts, Tar and feathering, Pamphleteering |

| Notable attacks | Gaspee Affair, Boston Tea Party, Attack on John Malcolm |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

| Great Seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Versions | |

| |

| Armiger | Commonwealth of Massachusetts |

| Adopted | December 13, 1780 |

| Motto | Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem |

The Great Seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts contains the coat of arms of Massachusetts. The coat of arms is encircled by the Latin text "Sigillum Reipublicæ Massachusettensis" (literally, The Seal of the Republic of Massachusetts). The Massachusetts Constitution designates the form of government a "commonwealth," for which Respublica is the correct Latin term. The Seal uses as its central element the Coat of Arms of Massachusetts. An official emblem of the State, the Coat of Arms was adopted by the Legislature in 1775, and then reaffirmed by Governor John Hancock and his Council on December 13, 1780. The present rendition of the seal was drawn by resident-artist Edmund H. Garrett, and was adopted by the state in 1900.[1] While the inscription around the seal is officially in Latin, a variant with "Commonwealth of Massachusetts" in English is also sometimes used.[2]

Coat of Arms

[edit]| Commonwealth of Massachusetts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Coat of Arms | The simplified coat of arms used in the state flag and larger signage[3] | Historical coat of arms (1876), adopted 1775. | |

Symbolism

[edit]History

[edit]Colony of New Plymouth

[edit]| Plymouth Colony | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Seal of the Plymouth Colony, (c. 1620–1629) | |||

Colony of Massachusetts Bay

[edit]| Massachusetts Bay COlony | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, (1629–1686, 1689-1691) | |||

Dominion of New England

[edit]| Dominion of New England | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

| Seal used by the Colonial Administration | Coat of Arms of James II of England | Coat of Arms of William and Mary during their joint reign | |

Province of Massachusetts Bay

[edit]| Province of Massachusetts Bay | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Coat of Arms of William and Mary | Coat of Arms of Queen Anne from 1702-1707 | Coat of Arms of Queen Anne from 1702-1714 | Coat of Arms of George I. George II, and George III |

Massachusetts Provincial Congress

[edit]| Massachusetts Bay Provincial Congress of Deputies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Seal used by the Provincial Congress | |||

Controversy over Minuteman's sword and Native American imagery

[edit]Civil advocates demanded that the imagery in the State Seal (and on the Flag of Massachusetts that displays it) had to change, due to the Colonial broadsword's placement directly above the Native American depiction's head as a "form of white supremacist imagery".[4][5]

On January 11, 2021, Governor Charlie Baker signed a bill establishing a commission to change the state flag and seal.[6]

Government Seals of Massachusetts

[edit]-

Seal of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

-

Seal of the Massachusetts Senate

-

Alternative seal of the Massachusetts Senate

-

Seal of the Massachusetts State Police

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Garrett, E. H. (1901). "The Coat of Arms and Great Seal of Massachusetts". The New England Magazine. XXIII (6). Boston: Warren F. Kellogg: 623–635.

- ^ House of Representatives Proclamation

- ^ 950 CMR 34.00: Commonwealth of Massachusetts Flags, Arms, and Seal Specifications

- ^ Markos, Mary (July 16, 2020). "Renewed Calls to Change the Massachusetts State Flag". nbcboston.com. NBC Boston. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

Advocates claim that Massachusetts is "the last U.S. state whose flag includes representations of white supremacy" now that Mississippi has retired the confederate state flag.

- ^ https://www.wbur.org/news/2019/11/19/state-seal-flag-symbols-native-americans-massachusetts

- ^ https://changethemassflag.com/2021/01/12/governor-baker-signs-the-bill-establishing-a-special-commission-to-change-the-mass-flag-and-seal/

External links

[edit]- The History of the Arms and Great Seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

- Arms of Massachusetts, American Heraldry Society

Massachusetts

Category:Symbols of Massachusetts

Massachusetts

Massachusetts

Massachusetts

Category:Political controversies in the United States

Category:Native American-related controversies

Category:Race-related controversies in the United States

United Colonies of New England | |

|---|---|

| 1643–1686 | |

| |

| Status | Dissolved |

| Religion | Puritanism |

| Demonym(s) | New Englander |

| Government | Directional Confederation and Military Alliance |

| Commissioner | |

| Historical era | Great Migration, British colonization of the Americas, American Indian Wars, Anglo-Dutch Wars |

• Established | May 19 1643 |

• Disestablished | 1686 |

| |

Hosts

[edit]Nicholas "Nick" Mullen (Born: December 13, 1988) is a standup comedian, voice actor, and comedy writer. He was born in New York City and raised the Greater Baltimore area. Mullen has also lived in Austin, Texas and Los Angeles, California. Mullen has stated that he has worked numerous jobs throughout the years including time as a pizza delivery driver and film production assistant.

Stavros Halkias (Greek: Σταύρος Χαλκιάς; born: February 11, 1989) is a Greek-American standup comedian. Halkias was born in Baltimore, Maryland to Greek immigrants. His family was active in the Greek Communist Party, with many members having to seek refuge in neighboring countries at various times. He was raised in Baltimore's Greektown and attended the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Following graduation, while persuaing comedy Halkias also worked as a paralegal. Halkias currently lives in Astoria, Queens.

Adam Friedland (Born: April 10, 1987) is a South African American comedian. Friedland was born in Santa Monica, California to South African parents of Lithuanian Jewish decent. His parents left South Africa due to their opposition to the Apartheid white minority regime. During his childhood Friedland lived in Los Angeles, Capetown, and Las Vegas. Friedland attended George Washington University, graduating in 2009. Initially he sought to pursue a legal career however decided to become a comedian instead.

{{Culture of region

| name = Culture of New England

| region = New England

| image = File:Ensign of New England (pine only).svg|border

| imagesize = 150

| ethnooverride = Demographics of New England

| langtopics =

| tradtopics =

| cuistopics =

| festoverride = Holidays | festtopics =

- Patriot's Day

- Evacuation Day

- Bunker Hill Day

- Feast of the Blessed Sacrament

- National Acadian Day

- Bennington Battle Day

| littopics =

| sporttopics =

- [[Sports in New England

| symbtopics =

}}

| This is the sandbox page for User:Tpwissaa (diff). |

| Sons of Liberty | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

| Foundation | 1765 |

| Dissolved | 1776 |

| Motives | Before 1766: Repealing of the Stamp Act After 1766: Independence of the United Colonies from Great Britain |

| Active regions | New England Colonies

|

| Ideology | Initial: No taxation without representation Later: Republicanism Independence from Great Britain |

| Major actions | Public demonstrations, Direct action, Destruction of Crown goods and property, Boycotts, Tar and feathering |

| Notable attacks | Boston Tea Party, Attack on John Malcolm |

| Allies | Patriot revolutionaries |

| Opponents | Kingdom of Great Britain Royal Colonial Governments Loyalists |

| Sons of Liberty | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

| Leaders | See below |

| Foundation | 1765 |

| Dissolved | 1776 |

| Motives | Before 1766: Repealing of the Stamp Act After 1766: Independence of the United Colonies from Great Britain |

| Active regions | Province of Massachusetts Bay Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Province of New Hampshire Province of New Jersey Province of New York Province of Maryland Province of Virginia |

| Ideology | Initial: Rights of Englishmen "No taxation without representation" Later: Republicanism Independence from Great Britain |

| Major actions | Public demonstrations, Direct action, Destruction of Crown goods and property, Boycotts, Tar and feathering |

| Notable attacks | Boston Tea Party, Attack on John Malcolm |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | Loyalists |

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a British colony located on the east coast of America. The colony was founded as a merger of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Plymouth Colony through royal charter in 1691. The largest and most populous of the New England Colonies, the province included, along with its main constituent colonies of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth, the lands of Acadia, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Maine. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is its direct successor, Maine has been a separate state since 1820, and Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are now Canadian provinces, having been part of the colony only until 1697.

Massachusetts Bay was one of the Thirteen Colonies which rebelled against the Kingdom of Great Britain and was a major center for revolutionary patriot thought and action. Pivotal events such as the Boston Tea Party and the Boston Massacre, which helped set the stage for war, took place in the province. The initial fighting of the revolution took place in Middlesex County at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Due to independent nature of the colonists and persistent revolutionary activity, the government of the colony changed during its existence. Originally a semi-autonomous and self governing, the province found itself at odds with the government of Great Britain and was made a direct rule colony in 1774. With the onset of the Boston Campgain the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was established. The Provincial Congress governed the colony until 1780, when a new constitution was adopted.

The name Massachusetts comes from the Massachusett Indians, an Algonquian tribe. It has been translated as "at the great hill", "at the place of large hills", or "at the range of hills", with reference to the Blue Hills and to Great Blue Hill in particular.

Flags with modern usage

-

New England red ensign (without St. George's Cross)

-

Red Ensign with St. George's cross in the canton.

-

Blue Ensign of New England, also known as the Bunker Hill flag

-

Blue ensign, field defaced with six stars. Flag of the New England Governor's Conference

-

New England Acadians

Historical flags

-

Red Ensign of the Kingdom of England

-

Red ensign with cross removed

-

Naval Jack drawn by John Graydon in 1686, consisting of St George's cross with a pine tree in the canton.[1]

-

Endecott Flag of early New England[2]

-

Blue ensign variant with armillary sphere in canton instead of the Pine[3]

-

New England variant of the Union Flag[4]

-

Revolutionary War variant flag of New England[5]

-

Revolutionary War variant flag of New England[6]

-

Dominion of New England banner, also known as the Andros Flag

-

New England Green Ensign[7]

-

New England green ensign after defacement[8]

Military

Territorial

-

Haverhill, Massachusetts, green ensign defaced with town seal

Related Flags

-

Flag of Massachusetts reverse (1908-1971)

-

Vermont Republic, also known as Green Mountain Boys flag

I have noticed some issues with dating in the infobox of the article. I wanted to start a discussion in talk page to clarify the problems. First the date given for the time-span of the colony is 1691-1776. While it is true that the United Colonies declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, the Province of Massachusetts Bay continued to exist as a political entity until the adoption of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780. The government type section also seems incomplete. The dates, government type, officials are all correct however they do not give a complete account. After 1775 Thomas Gage no longer had effective control of the Province and the governing of Massachusetts Bay was under the control of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress until the 1780 adoption of the Massachusetts Constitution. Also the timeline of significant events As with other historical states that have remained the same entity but gone through significant changes in government structure, I believe the infobox should reflect these changes. As the amount of changes needed wouldn't be minor I wanted to address these problems here.Tpwissaa (talk) 19:07, 13 July 2020 (UTC)

| blank_name_sec1 = Languages

| blank_info_sec1 = Creole languages

}}

Archbishop of Salzburg (1112–1555)

Habsburg Monarchy (1555–1804)

Austrian Empire (1804–1809, 1814–1867)

Illyrian Provinces (1809–1814; capital)

Austria-Hungary (1867–1918)

State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (1918)

Kingdom of Yugoslavia[15] (1918–1941)

Kingdom of Italy (1941–1945; occupied)

Nazi Germany (1943–1945; de facto)

SFR Yugoslavia[16] (1945–1991)

Slovenia (1991–present)

Plymouth Colony | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1620–1686 1689-1691 | |||||||||

Plymouth Colony town locations | |||||||||

| Status | Disestablished | ||||||||

| Capital | Plymouth | ||||||||

| Common languages | English | ||||||||

| Religion | Puritanism | ||||||||

| Government | Autonomous self-governing colony | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1620-1621 | John Carver (first) | ||||||||

• 1689-1692 | Thomas Hinckley (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | General Court | ||||||||

| Historical era | British colonization of the Americas Puritan migration to New England (1620-1640) | ||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||

| 1621 | |||||||||

| 1636-1638 | |||||||||

• New England Confederation formed | 1643 | ||||||||

| 1675-1676 | |||||||||

• Disestablished, reorganized as the Province of Massachusetts Bay | 1686 1689-1691 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Confrontation with England

[edit]Since the founding of Massachusetts Bay, England had difficulty enforcing its laws and regulations on the colony. Massachusetts Bay was a Company colony which differed from other colonies in British North America. Unlike the Royal Colonies and Proprietary colonies the English Crown administrated, Massachusetts Bay was largely self-governing with its own House of Deputies, Governor, and other self-appointed Officers. Also unlike even other company-colonies, Massachusetts Bay did not keep its headquarters, governor, etc. in London but instead moved them to the colonial plantation. This ability and tradition of self-rule coupled with the theocratic nature of New England Puritan society meant that the Massachusetts Bay colonists thought of themselves as something apart from their "mother country" of England. The Puritan founders of Massachusetts and Plymouth saw themselves as having been divinely given their lands in the New World with a duty to implement and observe religious law. With the end of the Commonwealth of England and the reinstatement of the monarchy these division were exacerbated by many Puritan colonists having sympathy and similar beliefs to the Parliamentarians. With the relative weakness of the Royal administration to take control of the colonists at the issuing of the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company to the strengthening of the monarchy towards the end of the 17th century, Massachusetts Bay and the other New England Puritan colonies had remained largely independent.[17]

When New Netherland was taken by the English in 1664 the Crown sent Royal Commissioners from the new Province of New York to New England to investigate the status of the government and legal system of the colonies. These Commissioners were tasked to bring the colonies into the fold and establish a more robust connection between England and the colonies, including allowing the Crown to nominate the Governor of the colony. This request was refused by the colonists who claimed the King had not right to "supervise [Massachusetts Bay's] laws and courts",[18] further saying that as long as the colonists remained within the legal rights and privileges of their charter that they ought to continue on as they were. When the Commissioners asked that the colony pay its obligated 20% of all gold and silver found in their claim in New England the colonists responded that they were "not obligated to the king but by civility".[19]

At the time in Massachusetts Bay there existed growing strife between the faction of more conservative Puritan political elite and the more moderate members of the colony. Massachusetts Bay extended the right to vote to only Puritan citizens leaving non-Puritans were excluded from civil society. With the population of the colony increasing and the non-Puritan population growing along with it there was tension and conflict as to the future direction of the colony. Many wealthy merchants and colonists wished to expand their economic base and commercial interests and saw the faction of conservative theocrats as thwarting that. Even among Puritan society the younger generation wished to liberalize society in a way which would help with commerce. Those who wanted Massachusetts Bay and New England to be a place for religious observance and theocracy were most hostile to any change in governance. When the Crown learned of these divisions they sought to have the enfranchisement of colonists expanded to include non-Puritans in hopes of a change in the managing of the colony.[20]

The charges of insubordination against the colony included the denial of the ability of the Crown to legislate in New England, the fact that Massachusetts Bay was governing in the Province of New Hampshire and Maine, and the denial of freedom of conscience. However chief among the colonists transgressions was their violations of the Navigation Acts. The Navigation Acts were passed by Parliament to regulate trade within the English colonial empire. These regulations determined how and who the colonies could trade with. New England merchants were flaunting these laws by trading sometimes directly with European powers in Continental Europe. This infuriated many merchants, commercial societies, and Royal committees in London who petitioned the King for action claiming that the New England colonists were hurting their trade. The Lords of Trade's complaints were so serious that the King sent Edward Randolph to Boston in an attempt to rein in and regulate the colony. When he arrived in Boston he found a colonial government which refused to give into the Royal demands. Randolph reported to London that the General Court of Massachusetts Bay claimed the King had no right to interfere with the dealings of Massachusetts Bay. In response Randolph asked the Crown to halt and cut off all trade to and from the colony and further regulations be put in place. The Crown did not wish to enforce such a harsh measure and risk alienating the moderate members of New England society which supported England so they attempted to offer conciliatory measures if Massachusetts Bay followed the law. When these attempts at reconciliation were refused the Lords of Trade became wary of the colony's charter and further petitioned the Crown to either revoke or amend it. Edward Randolph was made head of Customs and Surveyor General of New England with his office in Boston. Despite this increased pressure, the General Court established laws which allowed merchants to circumvent Randolph's authority. Adding to Randolph's frustration was the fact that he relied on the Admiralty Court (which was controlled by the General Court} to rule on the laws he was attempting enforce. The moderate faction of the General Court was supportive of Randolph and the changes the Crown wished to make but the conservatives remained too powerful and blocked any attempt to side with England. However as the tensions mounted between the Crown and Massachusetts Bay and threats of legal action against the colony mounted, the General Court did pass laws which acknowledged certain English admiralty laws while still allowing for self-governance. This legislation was not seen as enough and Randolph's inability to exercise power meant that tension was still high.[21]

Revocation of the charter

[edit]Threatened with a quo warranto by the Crown, two delegates from Massachusetts Bay were sent to London to meet with the Lords of Trade. The Lords demanded a supplementary charter to alleviate problems. However the agents sent by the General Court were under orders that they could not negotiate any change with the Charter and this only further enraged the Lords. As a result the quo warranto was issued against the Colony at once. The King, fearing this would stir problems within the colony, attempted to reassure the colonists that their private interests would not be infringed upon. The declaration did create problems however and political confrontation between the moderates and conservatives began. The moderates controlled the office of Governor and the Council of Assistants, and the conservative faction controlled the Assembly of Deputies. This political turmoil ended in compromise with the Deputies voting to allow the delegates in London to be able to negotiate and defend the colonial charter. Political confrontation spilled over into civil strife as the Puritan elite in Boston wished to continue to defend their charter and status quo theocratic governance, and those disenfranchised non-Puritans wishing to change Massachusetts Bay into a Royal colony that would extend to them rights and privileges.[22]

When the warrant arrived in Boston the General Court voted on what course the colony should take. The two options they had were to immediately submit to royal authority and dismantle their government or to wait for further action and for the Crown to revoke their Charter and install a new governmental system. The General Court decided to wait out the Crown. Although they lacked a legal basis to continue their government it remained intact until its official revocation in 1686.[23]

Initially the General Court consisted of the Governor of the colony, the Council of Assistants (an advice and consent body), and all the colonies Freemen. Unlike other New England colonies which used a more representative system, such as the Massachusetts Bay Colony, all the officers of the General Court were directly elected by the Freemen. At this early stage of the Colony's history the body of Freemen consisted of only the signatories to the Mayflower Compact. The Governor and Assistants acted as magistrates with legislative function being reserved for the Freemen in an open assembly. This form of direct democracy was similar to the open town meeting system still in place in many New England towns. However this method of governance did not last due to the inconvenience and cost of travel that colonists would have to endure to meet at the General Court. In 1639 changes were made which allowed Freemen of each town of the colony to elect from themselves 2 magistrates/delegates, the town of Plymouth was allowed 4. These delegates would act as local magistrates who could hear local cases and would also serves as delegates to the General Court. There were provisions which allowed these delegates to be removed from office if they were found to be "troublesome". Some elements of direct democracy remained, such as the officers continuing to be elected from the whole body of freemen and not the by delegates of the Court.[24]

Who counted as a Freemen changed over the history of the Plymouth Colony. The original restrictions, limiting the freemen to those original Compact signatories was amended to include additional signatories. Some exclusions to this included groups as Quakers and Ranters. Signing of the compact required an oath of fidelity, and since groups such as Quakers are not permitted to take oaths they were to be excluded from Plymouth political life. In 1671 the qualifications for Freemen liberalized again. Any Puritan man over 21 years old who possessed property worth over £20 could be considered.[25]

Davis, William T. (1900). History of the Judiciary of Massachusetts, Including the Plymouth and Massachusetts Colonies, the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and the Commonwealth. The Boston Book Company. ISBN 9780306706134.

History and predecessor bodies

[edit]Plymouth Colony

[edit]On December 17, 1623 the Plymouth Colony passed a resolution which declared that juries of 12 men would try "all criminal facts and all matters of trespass and debts". Before 1685 there existed four avenues for legal proceedings. The General Court (the colony's legislature), the Court of Assistants, the Admiralty Court, and Selectman's Court. The General Court, which functioned largely as the colony's legislature, consisted of the Governor, the Council of Assistants, and all the freeman of the colony. Due to the size of the colony at the time this type of judiciary was found to be inconvenient because of the constant travelling the freemen of the colony were forced to due. As a result the General Court decided that each town of the colony (towns other than Plymouth included: Duxbury, Scituate, Yarmouth, Taunton, Barnstable) were to nominate 2 freeman to act as judges and magistrates for local legal affairs. The town of Plymouth due to its larger population was allowed 4 freemen to act as magistrates. If any of the freemen were found to be insufficient in their duties then they may be dismissed. The open town meeting system of the colony allowed for any law passed by the General Court or magistrates to be repealed by popular vote. The qualifications of who constituted a Freeman changed throughout the colony's history. The title of Freeman initially was reserved to those who signed the Mayflower Compact but by 1671 it was extended to men "...twenty-one years of age, of sober mind and peaceful conversation, orthodox in the fundamentals of religion, and possessed of twenty pounds ratable estate in the Colony." The General Court met three times a year for the purpose of deciding legal proceedings. The Court of Assistants met three times a year. During these sessions the court would decide upon civil, criminal, and capital cases, as well as appellate cases. The most local level of judiciary, the Court of Selectmen, was established in 1661. The Selectmen were to be elected by the freemen of their respective towns and deal as magistrates with local legal affairs. Each town would have 3 or 5 freemen for the role. The Admiralty Court was made up of the Governor of the colony as well as a handful of members of Council of Assistants. This court dealt with maritime affairs, be it robberies, treason, piracy etc. There existed another legal structure which dealt with Indian affairs. These magistrates, sometimes styled Tithingman, were members of the Council of Assistants who were chosen to oversee and legal issue between Indian members of the colony.

Massachusetts Bay Colony

[edit]The Massachusetts Bay Colony had a General Court which initially consisted of the Governor, Deputy Governor, Council of Assistants, and all the other Freemen of the colony. The General Court met in session four times a year, and an additional four monthly meetings consisting of the executive officers of the Court. Unlike the Plymouth Colony, with its more direct democracy, the Massachusetts Bay General Court elected its officers through indirect elections. The Freemen were to elect the Assistants who then in turn would elect the Governor and Deputy Governor from among themselves. The colonists made the General Court the supreme authority in the colony, giving it alone the power to make and pass laws, tax, appoint officers, and apportion properties. In the early years of the Colony all trials were presided over by the General Court and Court of Assistants. With the colonists commitment to strict Puritan teachings they enacted laws that were based on the biblical Laws of Moses. In 1639 changes were made to the composition of Massachusetts Bay's judiciary. The General Court was reorganized to include the Governor, Deputy-Governor, Assistants, and legislative Deputies. The Court of Assistants, also known as the Great Quarter Courts, was scheduled to sit 4 times a year and was composed of the Governor and Deputy-Governor, and the Assistants. The next lower level of judiciary, the Inferior Courts, were composed of magistrates appointed by the General Court. As the years went on these Inferior Courts evolved into County level courts. These county level courts were also tasked with handling local Indian affairs. Cases not exceeding claims more than 20 shillings could be overseen by any of the General Court appointed magistrates who lived locally.

Province of Massachusetts Bay

[edit]Constitutional Role

[edit]

Providence is the capital and most populous city in Rhode Island, and the 3rd most populous in New England. The city covers just over 20 square miles and as of 2019 has an estimated population of 179,335. It is the traditional seat of Providence County, although county government was abolished in 1842. It is the principal city of the Providence metropolitan area, the 38th largest metro area in the United States. Providence is also a principal city of the Greater Boston area (along with Worcester, Massachusetts and Boston) which contains a large part of New England's population.

It was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian and religious exile from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He named the area in honor of "God's merciful Providence" which he believed was responsible for revealing such a haven for him and his followers. The city is situated at the mouth of the Providence River at the head of Narragansett Bay. Providence was one of the first cities in the country to industrialize and became noted for its textile manufacturing and subsequent machine tool, jewelry, and silverware industries.[26][27] Today, the city of Providence is home to eight hospitals and seven institutions of higher learning which have shifted the city's economy into service industries, though it still retains some manufacturing activity.

| The Articles of Confederation between the Plantations under the Government of the Massachusetts, the Plantations under the Government of New Plymouth, the Plantations under the Government of Connecticut, and the Government of New Haven with the Plantations in Combination therewith | |

|---|---|

| Type | Directional Confederation and Military Alliance |

| Context | Great Migration, British colonization of the Americas, American Indian Wars, Anglo-Dutch Wars |

| Drafted | May 19, 1643 |

| Parties | |

The United Colonies of New England, commonly known as the New England Confederation, was a short-lived military alliance of the New England colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven formed in May 1643. Its primary purpose was to unite the Puritan colonies in support of the church, and for defense against the American Indians and the Dutch colony of New Netherland.[28] It was the first milestone on the long road to colonial unity, and was established as a direct result of a war that started between the Mohegans and Narragansetts. Its charter provided for the return of fugitive criminals and indentured servants, and served as a forum for resolving inter-colonial disputes. In practice, none of the goals were accomplished.[29]

The confederation was weakened in 1654 after Massachusetts refused to join an expedition against New Netherland during the First Anglo-Dutch War, although it regained importance during King Philip's War in 1675. It was dissolved after numerous colonial charters were revoked in the early 1680s.

Treaty

[edit]With the expansion of the New England Colonies and their contact with the colonies of other European nations and Native tribes, New England colonial leaders sought an alliance and further integration. The treaty calls on the New England colonies as a nation, saying they share a way of life and religion. This alliance was meant to be a perpetual mode of defense and communication between the colonies themselves and any foreign threats.

The treaty contains 11 articles:

- That the colonies should form into a league of friendship with mutual military assurance. This relationship would ensure the communal safety and welfare of the colonies and preserve their Puritan way of life.

- The New England colonies were to maintain and keep their current territory. Their jurisdictions would remain unfettered by the other members of the confederation and any changes made thereafter would after would have to be agreed to by the other members.

- In the event of war all members of the confederation were bound to each other. This meant that they had to contribute whatever they were capable, in terms of men and provisions, to the war effort. The colonies would also be obligated to provide a census of all their available men for militia. All men from ages 16-60 were to be considered eligible for service. Any gains from military conflict were to be divided in a just manner among the confederation.

- If any member state of the confederation comes under attack then the other members must come to their aid without delay. This assistance would take place proportionally. Massachusetts Bay would be required to send 100 armed and supplied men, the other colonies 45 armed and supplied men or less based on proportionality. If a greater number of men or supplies are needed then the Commissioners of the Confederation would need to approve of the measure. If any confederation members is at fault in terms of war then they shall make just any obligations to the assisting members.

- Two Commissioners shall be chosen from each province (2 from Massachusetts Bay, 2 from Plymouth, 2 from Saybrook, and 2 from New Haven). These Commissioners were to be tasked with administration of martial affairs. Any agreement not reached by all members not unanimously can be settled by a majority vote of six. The Commissioners were to meet once a year unless there was an extraordinary situation which prompted the need of a meeting. The meetings were to take place the first Thursday of in September. The locations of these meetings are to be in a specific order, first Boston, second at Hartford, third New Haven, and fourth at Plymouth, with the cycle then repeating. If any meeting place was found to be unfit then another may be decided.

- The Commissioners would select a President from among themselves with a minimum 6 votes. This President would not have any extra powers and would serve a purely administrative function.

- Commissioners would have power to draft law and codes that would benefit the general welfare of the Confederation. These laws would be to

See also

[edit]- Dominion of New England, an entirely different entity, 1686–1689

- History of New England

- New England Colonies

References

[edit]- ^ Historical Flags of Our Ancestors. "Flags of the Early North American Colonies and Explorers". Loeser.is. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Crouthers 1962, p.24.

- ^ Crouthers 1962, p.26.

- ^ Lossing, Chapter 23, endnote 19

- ^ "New England flags (U.S.)". Fotw.info. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Hulme 1896, fig. 14.

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.12

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.14

- ^ Hulme 1896, fig. 14.

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.33.

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.24.

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.23.

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.23.

- ^ Martucci 2006, p.23.

- ^ Known as: Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918–1929)

- ^ Known as: Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1963); Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1963–1992)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.6)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.7)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.7)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.8-10)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.10-18)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.18-23)

- ^ (Barnes 1923, p.23)

- ^ {Davis 1900, p.7-8)

- ^ (Davis 1900, p.8-9

- ^ "Providence Architecture". brown.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Kupperman, Karen Ordahl (June 1995). Providence Island, 1630–1641: The Other Puritan Colony. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-521-35205-3.

- ^ William Henry Carpenter, Timothy Shay Arthur. The history of Connecticut: from its earliest settlement to the present time (1872) ch 5

- ^ John Andrew Doyle. English Colonies in America: The Puritan colonies (1889) ch 8

External links

[edit]- The Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England Settlements

- New England Confederation

42°02′31″N 72°07′19″W / 42.042°N 72.122°W

Category:1684 disestablishments in the Thirteen Colonies Category:States and territories established in 1643 Category:History of New England Category:Former confederations Category:1643 establishments in the Thirteen Colonies

| Company type | Joint-stock company, Land grant, Colonial Company |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Council for New England |

| Founded | 1629 |

| Defunct | 1692 |

| Fate | Charter revoked in 1684 |

| Successor | Incorporated into the Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Matthew Cradock. John Endecott, John Winthrop |

A

Province of Massachusetts Bay | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1691–1779 | |||||||||||||||||

Map depicting the colonial claims related to the province | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Boston | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Massachusett, Mi'kmaq | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Congregationalist | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Crown Colony | ||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||

• 1691–1694 | William III and Mary II | ||||||||||||||||

• 1760–1783 | George III | ||||||||||||||||

| Royal Governor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1692–1694 | Sir William Phips | ||||||||||||||||

• 1694–1774 | full list | ||||||||||||||||

• 1774–1775 | Thomas Gage | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Great and General Court | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | British colonization of the Americas/American Revolution | ||||||||||||||||

• Massachusetts Charter issued | October 7 1691 | ||||||||||||||||

• Provincial Congress established | October 4, 1774 | ||||||||||||||||

• Massachusetts Declaration of Independence | May 1, 1776 | ||||||||||||||||

• Admission to the Union | February 6, 1788 | ||||||||||||||||

• Massachusetts Constitution adopted | October 1 1779 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Massachusetts pound, Spanish dollar | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Canada, United States | ||||||||||||||||

| Boston City Charter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Jurisdiction | City of Boston |

| Subordinate to | Constitution of Massachusetts |

| Chambers | Boston City Council |

| Executive | Mayor of Boston |

The Boston City Charter is a series of State statutes which codifies a system of rules for the government of the City of Boston. The Charter is not a typical city constitution but rather a series of amendments, General Court rulings, and case law which form the basis of government. The central organs of the Boston City Charter are the Mayoral Office and City Council. The composition of these offices, their term length, manner of election, and scope of power have changed throughout the years.

History

[edit]Before 1822, when Boston was incorporated as a city, it shared a similar manner of government to other New England towns. This meant that Boston, then known as "Town of Boston", was governed by a 7 member Board of Selectmen who would elect then among themselves an executive office of "Intendant". To serve as legislature there was a "Board of Assistants". The Assistants were given a mix of legislative and executive powers and were elected from Boston's then 12 wards. As with other New England towns the town meeting was still to be the primary democratic body of Boston and these executive offices would govern when in between these general sessions.

First City Charter

[edit]When Boston voted to become a city in 1822, the position of Intendant was replaced with Mayor, the Board of Assistants was renamed the Common Council, and the Selectmen were renamed Aldermen. With the population growing, the citizens of Boston wanted change in the system of government. Many felt a town meeting form of government was insufficient and impracticable with Boston's increasing population. Logistically speaking a town meeting was near impossible due to the fact there was no hall large enough to fit all eligible voters. The changes brought forward in 1822 for the reorganization of local government were passed with 2797 votes for and 1881 against. Some citizens, including John Quincy Adams, were worried the new manner of government would be susceptible to corruption and that the "pure democracy of a town meeting [was] more suited to the character of the people of New England."

This new government was to have a Mayor as chief executive officer who was elected to a 1 year term, 8 Aldermen, as well as 1 member of each ward being elected to a School Committee. The School Committee, along with the Aldermen and Mayor, would be in charge of education in the City. The Mayor was not an independent actor and instead would operate alongside the Alderman. The Mayor would be presiding officer of this executive board but would not have veto power. The Mayor did however have the sole power to nominate candidates for city office.

The Mayor and Aldermen would serve as the upper part of the City Council, with the lower part being made up of 4 members from each of Boston's 12 wards. These two branches of the Council would have negative power over each other. The upper part taking the role of Selectmen from the old system and the lower part taking the role of the open town meeting. The two parts were to have similar executive power in order to quell concerns from some citizens as to what they saw as a deterioration of the traditional form of New England democracy.

Revised Charter of 1854

[edit]Following the incorporation of Boston as a city in 1822 and formation of a city government, the next time large changes were made to local government came in 1854. Boston's population was exploding, from 43298 in 1820 to 138788 people in 1850, and with the increase in population many felt the need to once again reform the government. The main changes made were the expansion of the Board of Aldermen from 8 members to 12, the enlargement of the School Committee to 6 members from each ward, and the removal of the Mayor's right to vote at executive board meetings.

Acts of 1909

[edit]The modern government of Boston can be traced to a 1909 [act] of the Massachusetts General Court. In this act the General Court abolished the offices of Aldermen, Street Commissioner, Clerk of the Common Council, Clerk of Committees, and all the subordinate offices of these officials. The act replaced and centralized these positions into the Office of Mayor and City Council. The Council, with approval from the Mayor, was given the power to create offices it saw fit and appoint and remove the holders of these offices. The Council was also given power of approving the budget, as presented by the Mayor. The City Council was also to be given power of land use (with exception of School land), and the purchase and sale of that property.

The Council was to have 9 members. The three candidates with the highest number of votes would serve a term of three years, the three next highest a term of two years, next largest a term of 1 year. The members of the City Council would vote among themselves as to the President of the Council for the municipal year. The Mayor would be elected to office for a 4 yer term and was subjected to the possibility of recall after 2 years.

Modern Institutions

[edit]Boston's current charter states there is to be a Mayor, elected to a 4 year term, who is the city's chief executive. The Mayor in capacity as chief executive is to approve any ordinance, order, or resolution from the City Council they see fit. The City Council is to maintain legislative functions, control of the City budget, create agencies, making land use decisions, and serve as check to the Mayor's executive. The City Councilors are to receive a salary that is 50% of the Mayor's.

Sources

[edit]- Olin, William, ed. (1909). Acts and Resolves passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the year 1909. Boston: Secretary of the Commonwealth, Wright and Potter Printing Co.

- Bugbee, James, ed. (1887). The City Government of Boston. Baltimore: John Hopkins University.

- Walton Advertising and Print co., ed. (1922). Boston, one hundred years a city : a collection of views made from rare prints and old photographs showing the changes which have occurred in Boston during the one hundred years of its existence as a city, 1822-1922. State Street Trust Company.

- https://www.cityofboston.gov/images_documents/2007%20the%20charter%20draft20%20%28final%20draft1%20with%20jumps%29_tcm3-16428.pdf

| Boston City Charter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Jurisdiction | City of Boston |

| Subordinate to | Constitution of Massachusetts |

| Chambers | Boston City Council |

| Executive | Mayor of Boston |

The Boston City Charter is a series of State statutes which codifies a system of rules for the government of the City of Boston. The Charter is not a typical city constitution but rather a series of amendments, General Court rulings, and case law which form the basis of government. The central organs of the Boston City Charter are the Mayoral Office and City Council. The composition of these offices, their term length, manner of election, and scope of power have changed throughout the years.

History

[edit]Before 1822, when Boston was incorporated as a city, it shared a similar manner of government to other New England towns. This meant that Boston, then known as "Town of Boston", was governed by a 7 member Board of Selectmen who would elect then among themselves an executive office of "Intendant". To serve as legislature there was a "Board of Assistants". The Assistants were given a mix of legislative and executive powers and were elected from Boston's then 12 wards. As with other New England towns the town meeting was still to be the primary democratic body of Boston and these executive offices would govern when in between these general sessions.

First City Charter

[edit]When Boston voted to become a city in 1822, the position of Intendant was replaced with Mayor, the Board of Assistants was renamed the Common Council, and the Selectmen were renamed Aldermen. With the population growing, the citizens of Boston wanted change in the system of government. Many felt a town meeting form of government was insufficient and impracticable with Boston's increasing population. Logistically speaking a town meeting was near impossible due to the fact there was no hall large enough to fit all eligible voters. The changes brought forward in 1822 for the reorganization of local government were passed with 2797 for and 1881 against. Some citizens, including John Quincy Adams, were worried the new manner of government would be susceptible to corruption and that the "pure democracy of a town meeting [was] more suited to the character of the people of New England."

This new government was to have a Mayor as chief executive officer who was elected to a 1 year term, 8 Aldermen, as well as 1 member of each ward being elected to a School Committee. The School Committee, along with the Aldermen and Mayor, would be in charge of education in the City. The Mayor was not an independent actor and instead would operate alongside the Alderman. The Mayor would be presiding officer of this executive board but would not have veto power. The Mayor did however have the sole power to nominate candidates for city office.

The Mayor and Aldermen would serve as the upper part of the City Council, with the lower part being made up of 4 members from each of Boston's 12 wards. These two branches of the Council would have negative power over each other. The upper part taking the role of Selectmen from the old system and the lower part taking the role of the open town meeting. The two parts were to have similar executive power in order to quell concerns from some citizens as to what they saw as a deterioration of the traditional form of New England democracy.

Revised Charter of 1854

[edit]Following the incorporation of Boston as a city in 1822 and formation of a city government, the next time large changes were made to local government came in 1854. Boston's population was exploding, from 43298 in 1820 to 138788 people in 1850, and with the increase in population many felt the need to once again reform the government. The main changes made were th expansion of the Board of Aldermen from 8 members to 12, the enlargement of the School Committee to 6 members from each ward, and the removal of the Mayor's right to vote at board meetings.

Acts of 1909

[edit]The modern government of Boston can be traced to a 1909 [act] of the Massachusetts General Court. In this act the General Court abolished the offices of Aldermen, Street Commissioner, Clerk of the Common Council, Clerk of Committees, and all the subordinate offices of these officials. The act replaced and centralized these positions into the Office of Mayor and City Council. The Council, with approval from the Mayor, was given the power to create offices it saw fit and appoint and remove the holders of these offices. The Council was also given power of approving the budget, as presented by the Mayor. The city Council was also to be given power of land use (with exception of School land), and the purchase and sale of that property.

The Council was to have 9 members. The three candidates with the highest number of votes would serve a term of three years, the three next highest a term of two years, next largest a term of 1 year. The members of the City Council would vote among themselves as to the President of the Council for the municipal year. The Mayor would be elected to office for a 4 yer term and was subjected to the possibility of recall after 2 years.

Modern Institutions

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Olin, William, ed. (1909). Acts and Resolves passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the year 1909. Boston: Secretary of the Commonwealth, Wright and Potter Printing Co.

- Bugbee, James, ed. (1887). The City Government of Boston. Baltimore: John Hopkins University.

- Walton Advertising and Print co., ed. (1922). Boston, one hundred years a city : a collection of views made from rare prints and old photographs showing the changes which have occurred in Boston during the one hundred years of its existence as a city, 1822-1922. State Street Trust Company.

- https://www.cityofboston.gov/images_documents/2007%20the%20charter%20draft20%20%28final%20draft1%20with%20jumps%29_tcm3-16428.pdf

| Boston City Charter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Jurisdiction | City of Boston |

| Subordinate to | Constitution of Massachusetts |

| Chambers | Boston City Council |

| Executive | Mayor of Boston |

The Boston City Charter is a series of State statutes which codifies a system of rules for the government of the City of Boston. The Charter is not a typical city constitution but rather a series of amendments, General Court rulings, and case law which form the basis of government. The central organs of the Boston City Charter are the Mayoral Office and City Council. The composition of these offices, their term length, manner of election, and scope of power have changed throughout the years.

History

[edit]Before 1822, when Boston was incorporated as a city, it shared a similar manner of government to other New England towns. This meant that Boston, then known as "Town of Boston", was governed by a 7 member Board of Selectmen who would elect then among themselves an executive office of "Intendant". To serve as legislature there was a "Board of Assistants". The Assistants were given a mix of legislative and executive powers and were elected from Boston's then 12 wards. As with other New England towns the town meeting was still to be the primary democratic body of Boston and these executive offices would govern when in between these general sessions.

First City Charter

[edit]When Boston voted to become a city in 1822, the position of Intendant was replaced with Mayor, the Board of Assistants was renamed the Common Council, and the Selectmen were renamed Aldermen. With the population growing, the citizens of Boston wanted change in the system of government. Many felt a town meeting form of government was insufficient and impracticable with Boston's increasing population. Logistically speaking a town meeting was near impossible due to the fact there was no hall large enough to fit all eligible voters. The changes brought forward in 1822 for the reorganization of local government were passed with 2797 for and 1881 against. Some citizens, including John Quincy Adams, were worried the new manner of government would be susceptible to corruption and that the "pure democracy of a town meeting [was] more suited to the character of the people of New England."

This new government was to have a Mayor as chief executive officer who was elected to a 1 year term, 8 Aldermen, as well as 1 member of each ward being elected to a School Committee. The School Committee, along with the Aldermen and Mayor, would be in charge of education in the City. The Mayor was not an independent actor and instead would operate alongside the Alderman. The Mayor would be presiding officer of this executive board but would not have veto power. The Mayor did however have the sole power to nominate candidates for city office.

The Mayor and Aldermen would serve as the upper part of the City Council, with the lower part being made up of 4 members from each of Boston's 12 wards. These two branches of the Council would have negative power over each other. The upper part taking the role of Selectmen from the old system and the lower part taking the role of the open town meeting. The two parts were to have similar executive power in order to quell concerns from some citizens as to what they saw as a deterioration of the traditional form of New England democracy.

Revised Charter of 1854

[edit]Following the incorporation of Boston as a city in 1822 and formation of a city government, the next time large changes were made to local government came in 1854. Boston's population was exploding, from 43298 in 1820 to 138788 people in 1850, and with the increase in population many felt the need to once again reform the government.

Acts of 1909

[edit]The modern government of Boston can be traced to a 1909 [act] of the Massachusetts General Court. In this act the General Court abolished the offices of Aldermen, Street Commissioner, Clerk of the Common Council, Clerk of Committees, and all the subordinate offices of these officials. The act replaced and centralized these positions into the Office of Mayor and City Council. The Council, with approval from the Mayor, was given the power to create offices it saw fit and appoint and remove the holders of these offices. The Council was also given power of approving the budget, as presented by the Mayor. The city Council was also to be given power of land use (with exception of School land), and the purchase and sale of that property.

The Council was to have 9 members. The three candidates with the highest number of votes would serve a term of three years, the three next highest a term of two years, next largest a term of 1 year. The members of the City Council would vote among themselves as to the President of the Council for the municipal year. The Mayor would be elected to office for a 4 yer term and was subjected to the possibility of recall after 2 years.

Mayor

[edit]Boston City Council

[edit]| Boston City Charter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Jurisdiction | City of Boston |

| Subordinate to | Constitution of Massachusetts |

| Chambers | Boston City Council |

| Executive | Mayor of Boston |

The Boston City Charter is a series of State statutes which codifies a system of rules for the government of the City of Boston. The Charter is not a typical city constitution but rather a series of amendments, General Court rulings, and case law which form the basis of government. The central organs of the Boston City Charter are the Mayoral Office and City Council. The composition of these offices, their term length, manner of election, and scope of power have changed throughout the years.

History

[edit]Before 1822 when Boston was incorporated as a city, it shared a similar manner of government to other New England towns. This meant that Boston, then known as "Town of Boston", was governed by a 7 member Board of Selectmen who would elect then among themselves an executive office of "Intendant". To serve as legislature there was a "Board of Assistants". The Assistants were given a mix of legislative and executive powers and were elected from Boston's then 12 wards. As with other New England towns the town meeting was still to be the primary democratic body of Boston and these executive offices would govern when in between these general sessions.

First City Charter

[edit]When Boston voted to become a city in 1822, the position of Intendant was replaced with Mayor, the Board of Assistants was renamed the Common Council, and the Selectmen were renamed Aldermen. With the population growing, the citizens of Boston wanted change in the system of government. Many felt a town meeting form of government was insufficient and impracticable with Boston's increasing population. Logistically speaking a town meeting was near impossible due to the fact there was no hall large enough to fit all eligible voters. The changes brought forward in 1822 for the reorganization of local government were passed with 2797 for and 1881 against. Some citizens, including John Quincy Adams, were worried the new manner of government would be susceptible to corruption and that the "pure democracy of a town meeting [was] more suited to the character of the people of New England."

This new government was to have a Mayor as chief executive officer who was elected to a 1 year term, 8 Aldermen, as well as 1 member of each ward being elected to a School Committee. The School Committee, along with the Aldermen and Mayor, would be in charge of education in the City. The Mayor was not an independent actor and instead would operate alongside the Alderman. The Mayor would be presiding officer of this executive board but would not have veto power. The Mayor did however have the sole power to nominate candidates for city office.

The Mayor and Aldermen would serve as the upper part of the City Council, with the lower part being made up of 4 members from each of Boston's 12 wards. These two branches of the Council would have negative power over each other. The upper part taking the role of Selectmen from the old system and the lower part taking the role of the open town meeting. The two parts were to have similar executive power in order to quell concerns from some citizens as to what they saw as a deterioration of the traditional form of New England democracy.

Acts of 1909

[edit]The modern government of Boston can be traced to a 1909 [act] of the Massachusetts General Court. In this act the General Court abolished the offices of Aldermen, Street Commissioner, Clerk of the Common Council, Clerk of Committees, and all the subordinate offices of these officials. The act replaced and centralized these positions into the Office of Mayor and City Council. The Council, with approval from the Mayor, was given the power to create offices it saw fit and appoint and remove the holders of these offices. The Council was also given power of approving the budget, as presented by the Mayor. The city Council was also to be given power of land use (with exception of School land), and the purchase and sale of that property.

The Council was to have 9 members. The three candidates with the highest number of votes would serve a term of three years, the three next highest a term of two years, next largest a term of 1 year. The members of the City Council would vote among themselves as to the President of the Council for the municipal year. The Mayor would be elected to office for a 4 yer term and was subjected to the possibility of recall after 2 years.

Mayor

[edit]Boston City Council

[edit]1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

====Puritanism==== https://books.google.com/books?id=gfOFDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=new+england+puritans&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjn6Y_5h8LnAhWkzVkKHam4Av04ChDoATAEegQIBhAC#v=onepage&q=new%20england%20puritans&f=false{Main%7CPuritanism%7CPuritan migration to New England (1620–1640)|Congregationalism in the United States}}

The settlers of the Plymouth Colony and the Massachusetts Bay Colony made 17th century New England the center for Puritan migration in the New World. These Puritan settlers shaped their settlements around their theological beliefs with the Massachusetts Bay Colony serving as a theocratic state following the Laws of Moses and the Congregationalism serving as the state religion. In 1643 representatives from settlements from southern New England gathered in Boston to draft a treaty of friendship and mutual defense amongst themselves. Setting out their purpose and uniting principles the assembly declared they had come to New England to settle and "advance the kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ" and for "propagating and preserving the truth and liberties of the gospel". The Puritan settlers extended their belief of a congregational and presbyterian polity to the civil aspects of government, with the magistrates and offices being held by elected officials chosen by the freemen of the colony. Along with the explicitly biblical laws enforced by the settlers there were additional theocratic ordinances passed which were meant to enact religious discipline. This included laws such as permitted activities on the sabbath, a ban on dancing, to the outlawing of gambling.

The Puritan movement in New England survives today through the United Church of Christ, and in its architectural legacy with many town centers having a Congregational Church as a focal point.

Universalism

[edit]Judaism

[edit]Catholicism

[edit]Suffolk County

Boston Thomas Cushing, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Joseph Warren, Benjamin Church, Nathaniel Appleton

Roxbury William Heath, Aaron Davis

Dorchester Lemuel Robinson

Milton David Rawson, James Boice

Braintree Ebenezer Thayer, Joseph Palmer, John Adams

Weymouth Nathaniel Bailey

Hingham Benjamin Lincoln

Cohasset Isaac Lincoln

Dedham Samuel Dexter, Abner Ellis

Medfield Moses Bullen, Seth Clark

Wrenthem Jabez Fisher, Lemuel Kollock

Brookline Benjamin White, William Thompson, John Goddard

Stoughton Thomas Crane, John Withington, Job Swift

Walpole Enoch Ellis

Medway Johnathan Adams

Needham Eleazer Kingsbury

Bellingham Luke Holbrook

Chelsea Samuel Watts

Essex County

Salem John Pickering, Jonathan Ropes

Danvers Samuel Holten

Ipswich Michael Farley, Daniel Noyes

Newbury Joseph Gerrish

Newburyport Jonathan Greenleaf

Marblehead Jeremiah Lee, Azor Orne, Elbridge Gerry

Lynn Ebenezer Burrill, John Mansfield

Andover Moody Bridges

Beverly Josiah Batchelder

Salisbury Samuel Smith

Haverhill Samuel White, Joseph Haynes

Gloucester Peter Coffin

Topsfield Samuel Smith

Borford Daniel Thurston

Wrenthem Benjamin Fairfield

Manchester Andrew Woodbury

Methuen James Ingles

Middleton Archelaus Fuller

Middlesex County

Cambridge John Winthrop, Thomas Gardner, Abraham Watson, Francis Dana

Charlestown Nathaniel Gorham, Richard Devens, Isaac Foster, David Cheever

Watertown Jonathan Brown, John Remington, Samuel Fisk

Woburn Samuel Wyman

Concord James Barrett, Samuel Whitney, Ephraim Wood Jr

Newton Abraham Fuller, John Pigeon, Edward Durant

Reading John Temple, Benjamin Brown

Marlborough Peter Bent, Edward Barnes, George Brigham

Billerica William Stickney, Ebenezer Bridge

Framingham Joseph Haven, William Brown, Josiah Stone

Lexington Jonas Stone

Chelmsford Simeon Spalding, Jonathan Williams Austin, Samuel Perham

Sherborne Samuel Bullard, Jonathan Leland

Sudbury Thomas Plimpton, Richard Heard, James Mosman

Malden Ebenezer Harnden, John Dexter

Medford Benjamin Hall

Weston Samuel P. Savage, Braddyl Smith, Josiah Smith

Hopkinton Thomas Mellon, Roger Dench, James Mellen

Waltham Jacob Bigelow

Groton James Prescott

Shirley Francis Harris

Pepperell William Prescott

Stow Henry Gardner

Townsend Jonathan Stow, Daniel Taylor

Ashby Jonathan Locke, Samuel Stone

Stoneham Samuel Sprague

Wilmington Timothy Walker

Natick Hezekiah Broad

Dracut William Hildreth

Bedford Joseph Ballard, John Reed

Holliston Abner Perry

Tewsbury Jonathan Brown

Acton Josiah Hayward, Francis Faulkner, Ephriam Hapgood

Westford Joseph Reed, Zaccheus Wright

Littleton Abel Jewett, Robert Harris

Dunstable John Tyng, James Tyng

Lincoln Eleazer Brooks, Samuel Farrar, Abijah Pierce

Hampshire County

Springfield Charles Pynchon, George Pynchon, Jonathan Hale

Wilbrham John Bliss

Ludlow Joseph Miller

West Springfield Benjamin Ely, Chauncy Brewer

Northampton Seth Pomeroy, Joseph Hawley

Southampton Elias Lyman

Hadley Josiah Pierce

South Hadlye Noah Goodman

Amherst Nathaniel Dickerson Jr

Granby Phineas SMith

Hatfield John Dickerson

Whateley Oliver Graves

Deerfield Samuel Barnard Jr

Greenfield Daniel Nash

Shelburne John Taylor

Conway Thomas French

Westfield and Southwick John Mosely, Elisha Parks

Sunderland Israel Hubbard

Montague Moses Gunn

Brimfield TImothy Danielson

South Brimfield Daniel Winchester

Monson Abel Goodale

Northfield Phineas Wright

Granville TImothy Robinson

New Salem William Page

Colrain THomas McGee

Belchertown Samuel How

Ware Joseph Foster

Warwick Samuel Williams

Charlemont Hugh Maxwell

Worthington Nahum Eager

Greenwich John Rea

Norwich Ebenezer Meacham

Plymouth County

Plymouth James Warren, Isaac Lothrop

Scituate Nathaniel Cushing, Gideon Vinal, Barnabas Little

Marshfield Nehemiah Thomas

Middleborough

Conférence des gouverneurs de la nouvelle angleterre et des premiers ministres de l'est du canada | |

| Nickname | NEG/ECP |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | New England Governor's Conference |

| Formation | 1973 |

| Type | Intergovernmental organization |

| Purpose | Cooperation of regional governments |

| Headquarters | Washington D.C. |

Region | New England The Maritimes Eastern Canada |

Secretary | Jay Lucey |

Executive Assistant | Tom Critzer |

Regional Program Coordinator | Lana Bluege |

Accountant | Elaine Murchinson |

Parent organization | Coalition of Northeastern Governors |

| Website | https://www.coneg.org/neg-ecp/ |

| |

| |

Native name | Massachusetts Bay Company |

|---|---|

| Company type | Joint-stock company, Land grant, Colonial Company |

| Predecessor | Council for New England |

| Founded | 1629 |

| Defunct | 1692 |

| Fate | Charter revoked in 1684 |

| Successor | Incorporated into the Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Matthew Cradock. John Endecott, John Winthrop |

Convention of Towns and growing crisis

[edit]

Following the passage of the Townshend Acts the General Court authorized a circular letter denouncing the acts as unconstitutional. The Royal Governor Francis Bernard demanded that the General Court rescind the letter and when the General Court refused he dissolved the assembly. This led to widespread violence and rioting throughout Boston. Royal officers fled to Castle William and the Crown authorized more troops to be sent to the province. The Sons of Liberty stated that they desired armed resistance to the Royal Authorities while other more conservative elements of society desired a peaceful political approach.

With the General Court dissolved it was resolved at a Boston town meeting to have the towns of the Province assemble in convention. Delegates met at Faneuil Hall for six days in September, with Thomas Cushing serving as chairman. Despite the insistence from more radical Patriot for armed resistance the more moderate factions of the convention won out and militant action was voted down.[1]

In 1773 in defiance of the Tea Act colonists of Massachusetts Bay's Sons of Liberty organized a meeting at the Old South Meetinghouse. Thousands of people attended and there Samuel Adams organized a protest at Boston harbor. Dressed as American Indians the colonists stormed ships stationed in the harbor and dumped the cargo of tea into the water. After the protest, later known as theBoston Tea Party, Hutchinson was replaced in May 1774 by General Thomas Gage.[2] Gage was well received at first, but his reputation rapidly became worse with the Patriots as he began to implement the Intolerable Acts. The Intolerable acts, which included the Massachusetts Government Act, dissolved the legislature, and closed the port of Boston until reparations were paid for the dumped tea. The port closure did great damage to the provincial economy and led to a wave of sympathetic assistance from other colonies.[3]

The Intolerable Acts only increased the crisis in the Province. With the dissolution of the General Court and the blockade of the Port of Boston colonists insisted that their constitutional rights were being destroyed. The colonists of Massachusetts Bay, going back to the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Plymouth Colony had quasi-democratic control of their government. The General Court, while lacking executive authority and authority over the militia, had significant power. The colonists were permitted to have control over the the treasury and spending and could pass and formulate laws. Anything passed by the assembly was subject to veto by the Royal Governor, however with the General Court having control over spending they could withhold the pay of the Royal officials as leverage. This resulted in the Royal Governor being sidelined at times to little more than a figurehead.[4]

With mounting political turmoil the more radical factions of colonial society began to ready themselves for armed confrontation. This crisis culminated in the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775.

Provincial Congress