User:Pietru/Sandbox:AOS

Intro[edit]

This diss is an exploration of asemic literature in the work of AOS. [exegesis of a primary and central text from AOS' "Book of Pleasure (Self-Love)".]

What is asemic literature?[edit]

Asemic writing has no specific semantic content, drawing inspiration from preliterate expressions whilst being a postliterate style of writing, suggesting meaning or existing as pure conception.

There is no verbal sense, though it may have clear textual sense through formatting and structure. It relies on the observer's aesthetic sensitivity. Asemic writing expresses relative perception, whereby unknown languages and forgotten scripts provide templates and platforms for new modes of expression.

experimental and canonical examples[edit]

* A Book from the Sky * Brion Gysin * Christian Dotremont * Codex Seraphinianus * Experimental literature * Henri Michaux * Lettrism * Postliterate society * Timothy Ely * Visual poetry * Voynich manuscript

Discuss the properties of asemic literature in psychoanalytic/mystical terms[edit]

?Asemic literature is a way of expressing the dynamic between unconscious and preconscious thoughts in a visual way.

base materialism[edit]

Bataille developed base materialism during the late 1920s and early 1930s as an attempt to break with mainstream materialism. Bataille argues for the concept of an active base matter that disrupts the opposition of high and low and destabilises all foundations. In a sense the concept is similar to Spinoza's neutral monism of a substance that encompasses both the dual substances of mind and matter posited by Descartes, however it defies strict definition and remains in the realm of experience rather than rationalisation. Base materialism was a major influence on Derrida's deconstruction, and both share the attempt to destabilise philosophical oppositions by means of an unstable "third term." Bataille's notion of Base Materialism may also be seen as anticipating Althusser's conception of aleatory materialism or "materialism of the encounter," which draws on similar atomist metaphors to sketch a world in which causality and actuality are abandoned in favor of limitless possibilities of action.

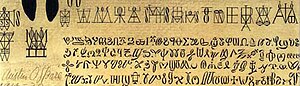

Sacred Alphabet[edit]

Sacred Alphabet or Alphabet of Desire are simplified forms of sigils that could be composed for expressing a desire. The philosophical background to "Alphabet of Desire" is extensively explained in The Book of Pleasure.

The first Sigillic formula to appear in Spare's published works can be seen in his second volume A Book of Satyrs.[1]

He designed and used a pack of cards which he called the Arena of Anon, each card bearing a magical emblem which was a variation of one of the letters of the Alphabet of Desire.[2]

Contextualise this in a postliterate society.[edit]

A postliterate society is a hypothetical society wherein multimedia technology has advanced to the point where literacy, the ability to read written words, is no longer necessary.

Postliterate is markedly different from preliterate. A preliterate society has not yet discovered how to read and write; a postliterate society has moved beyond the need for reading and writing.

Postliteracy is sometimes considered a sign that a society is approaching the technological singularity.

AOS[edit]

Austin Osman Spare (30 December 1886 - 15 May 1956) was an English artist who developed idiosyncratic magical techniques including automatic writing, automatic drawing and sigilization based on his theories of the relationship between the conscious and unconscious self. His artistic work is characterized by skilled draughtsmanship exhibiting a complete mastery of the use of the line, and often employs monstrous or fantastic magical and sexual imagery.

Place AOS in history.[edit]

Spare was born in Snow Hill, near Smithfield Market, London on 30 December 1886, the son of a City of London policeman. He was the fifth of six children.[3]

Spare studied at Lambeth Art School in 1899 under the guidance of Phillip Connard. At 14, one of his drawings was selected for inclusion in the British Art Section of the Paris International Exhibition. He subsequently trained at the Royal College of Art. Shortly thereafter, his father pressured him to send two drawings to the Royal Academy for consideration, with the result that one, an allegorical drawing was accepted.[4] At the age of only sixteen or seventeen, Spare had his work exhibited by the Royal Academy, creating something of a sensation. At this young age he was already deeply involved in the development of his esoteric ideas. In a 1904 article he is quoted as saying, regarding religion:

"I have practically none. I go anywhere. This life is but a reasonable development. All faiths are to me the same. I go to the Church in which I was born - the Established - but without the slightest faith. In fact, I am devising a religion of my own which embodies my conception of what we were, are, and shall be in the future."[5]

In October 1907 Spare had his first major exhibition at Bruton Gallery in London's West End. The content of this exhibition was striking, arcane and grotesque, causing controversy. These elements appealed to avant-garde London intellectuals, and perhaps brought him to the attention of Aleister Crowley, the infamous English mountaineer, magician and poet.[6] However they met, the two men certainly knew each other. Their interaction appears to have begun some time around 1907 or 1908, as a copy of the 1907 edition of A Book of Satyrs with an inscription (dated 1908) from Spare to Crowley is said to exist in a private collection.[7]

The two also engaged in written correspondence.[8] Spare almost certainly became a 'probationer' in the order "A∴A∴" or Argenteum Astrum (Latin for "Silver Star"), founded by Crowley and George Cecil Jones. Spare also contributed four small drawings to Crowley's periodical publication The Equinox[9], and a photograph exists which shows a young Spare with his hands at the sides of his face in the same pose which Crowley himself adopted in the famous 1910 photo with book, robe and hat.[10]

Whatever the nature of the relationship between Crowley and Spare it appears to have been short-lived, and a passage in Spare's The Book of Pleasure leaves no doubt that he did not hold a favorable view of ceremonial magic or magicians:

"Others praise ceremonial Magic, and are supposed to suffer much Ecstasy! Our asylums are crowded, the stage is over-run! Is it by symbolising we become the symbolised? Were I to crown myself King, should I be King? Rather should I be an object of disgust or pity. These Magicians, whose insincerity is their safety, are but the unemployed dandies of the Brothels."[11]

Spare married the actress and dancer Eily Gertrude Shaw on the 4th of September 1911. The two had met some years before. Whatever influence she may have had upon Spare's work the marriage was short-lived, though never formally dissolved. The two separated around 1918-19.[12] One known work of Spare's, inscribed, signed and dated as "Portrait of the Artist & His Wife March 26th 1912 AOS" is known. It shows the head of Spare executed in colored chalks and pencil. To one side, executed with only a few ghostly lines, we see the face of a woman with fine features, her head turned down and to the side, her eyes closed.[13]

The Book of Pleasure, published by Spare himself in autumn of 1913, most likely with the assistance of private patrons, is the most complete exposition of his esoteric ideas. "Conceived initially as a pictorial allegory the book quickly evolved into a much deeper work, drawing inspiration from Taoism and Buddhism, but primarily from his experiences as an artist."[14]

In 1917, during World War I, Spare was conscripted into the British army, serving as a medical orderly of the Royal Army Medical Corps in London hospitals, and was commissioned as an official War Artist in 1919. In this capacity he visited the battlefields of France to record the work of the R.A.M.C.[15]

Spare himself recalled, "When the war broke out, I joined the Army. When I left the Forces, the world was a very different place. Lots of things had changed. I found it very difficult to keep going on with what I had been doing. That pushed me into the abstract world - and there I have more or less remained."[16]

By 1927 Spare had certainly taken a public stance indicating disgust with contemporary society. Perhaps the time he spent documenting images of the horrors of war, followed by a period of financial instability and failing ventures, combined with often hostile reviews of his work and ideas led to this state of affairs. Whatever the cause, Spare's loathing was clearly expressed in his work Anathema of Zos - Sermon To The Hypocrites, which was published in that year. It was to be his last published book.

"Dogs, devouring your own vomit! Cursed are ye all! Throwbacks, adulterers, sycophants, corpse devourers, pilferers and medicine swallowers! Think ye Heaven is an infirmary?"[17]

Hannen Swaffer, the British journalist, reports that in 1936 Spare wilfully rejected a chance for international fame. He relates that a member of the German Embassy, buying one of Spare's self-portraits, sent it to Hitler. According to Swaffer, the Fuehrer was so impressed (according to this account because the eyes and the moustache were somewhat like his own) that he invited Spare to go to Germany to paint him. Spare, instead, made a copy of it, which came into Swaffer's possession. Swaffer indicates that written at the top of the portrait is the reply that Spare "sent to the man who wanted to master Europe and dominate mankind". Swaffer reports the reply read as follows: “Only from negations can I wholesomely conceive you. For I know of no courage sufficient to stomach your aspirations and ultimates. If you are superman, let me be for ever animal.” [18] This story is not the most incredible of the accounts which were (and are) in circulation regarding Spare. A number of anecdotes concerning Spare and his life have been recorded, many which include descriptions of magical occurrences, accurate divination or foreknowledge, and sorcerous manifestations. It should be said that whatever opinion one may hold regarding the truth of these tales, they are entirely in keeping with claims Spare himself is known to have made.

In 1941, fire and high explosive totally obliterated Spare's studio flat, depriving him of his home, his health and his equipment. For three years he struggled to regain the use of his arms until finally, in 1946, in a cramped basement in Brixton, he began to make pictures again, surrounded by stray cats. At the time he had no bed and worked in an old army shirt and tattered jacket. Yet he still charged only an average of £5 per picture. Clifford Bax, a friend of Spare's and a one-time collaborator recalled:

"Spare knew the taste of life as it is for people to whom a penny and a ha'penny are very different coins, and he lived in a high bleak barrack-like tenement block, among men and women in whose life elegance and the arts had no place, and surrounded by their washing and their cats. He said to me once 'Don't put 'esquire' on your letters. We've only one other esquire in my block, and they think we're giving ourselves airs.' His attractive simplicity came out, too, when he said 'If you are ever passing my place, do drop in'; for it is seldom that anybody happens to be passing The Borough unless he lives there."[19]

Spare was quoted as saying, “I have had a hard life, but I blame nobody but myself. I am responsible for my own misfortunes. I am rather apt to butt at a brick wall at times, and find, in the end, I cannot do any good about it. I cannot change things, so I give it my best.”[20] He died in London on 15 May 1956, at the age of 69.

Spare's work is remarkable for its variety, including paintings, a vast number of drawings, work with pastel, a few etchings, published books combining text with imagery, and even bizarre bookplates. He was productive from his earliest years until his death. According to Haydn Mackay, "rhythmic ornament grew from his hand seemingly without conscious effort."

Spare was regarded as an artist of considerable talent and good prospects, but his style was apparently controversial. Critical reaction to his work in period ranged from baffled but impressed, to patronizing and dismissive. An anonymous review of The Book of Satyrs published in December 1909, which must have appeared around the time of Spare's 23rd birthday, is by turns condescending and grudgingly respectful, "Mr. Spare's work is evidently that of young man of talent." However, "What is more important is the personality lying behind these various influences. And here we must credit Mr. Spare with a considerable fund of fancy and invention, although the activities of his mind still find vent through somewhat tortuous channels. Like most young men he seems to take himself somewhat too seriously". Our critic ends his review with the observation that Spare's "drawing is often more shapeless and confused than we trust it will be when he has assimilated better the excellent influences upon which he has formed his style."[21]

Two years later another anonymous review (this time of The Starlit Mire, for which Spare provided ten drawings) suggests, "When Mr. Spare was first heard of six or seven years ago he was hailed in some quarters as the new Beardsley, and as the work of a young man of seventeen his drawings had a certain amount of vigour and originality. But the years have not dealt kindly with Mr. Spare, and he must not be content with producing in his majority what passed muster in his nonage. However, his designs are not inappropriate for the crude paradoxes that form the text of this book. It is far easier to imitate an epigram than to invent one."[22]

In a 1914 review of The Book of Pleasure, the critic (again anonymous) seems resigned to bewilderment, "It is impossible for me to regard Mr. Spare's drawings otherwise than as diagrams of ideas which I have quite failed to unravel; I can only regret that a good draughtsman limits the scope of his appeal".[23]

From October 1922 to July 1924 Spare edited, jointly with Clifford Bax, the quarterly, Golden Hind for Chapman and Hall publishers. This was a short-lived project, but during its brief career it reproduced impressive figure drawing and lithographs by Spare and others. In 1925 Spare, Alan Odle, John Austen, and Harry Clarke showed together at the St George's Gallery, and in 1930 at the Godfrey Philips Galleries. The 1930 show was the last West End show Spare would have for 17 years.

Spare's obituary printed in The Times of May 16th, 1956 states:

"Thereafter Spare was rarely found in the purlieus of Bond St. He would teach a little from January to June, then up to the end of October, would finish various works, and from the beginning of November to Christmas would hang his products in the living-room, bedroom, and kitchen of his flat in the Borough. There he kept open house; critics and purchasers would go down, ring the bell, be admitted, and inspect the pictures, often in the company of some of the models - working women of the neighbourhood. Spare was convinced that there was a great potential demand for pictures at 2 or 3 guineas each, and condemned the practice of asking ₤20 for "amateurish stuff'. He worked chiefly in pastel or pencil, drawing rapidly, often taking no mon than two hours over a picture. He was especially interested in delineating the old, and had various models over 70 and one as old as 93."

But Spare did not entirely disappear. During the late 30s he developed and exhibited a style of painting based on a logarithmic form of anamorphic projection which he called "siderealism". This work appears to have been well received. In 1947 he exhibited at the Archer Gallery, producing over 200 works for the show. It was a very successful show and led to something of a post-war renaissance of interest.

Public awareness of Spare seems to have declined somewhat in the 1960s before the slow but steady revival of interest in his work beginning in the mid 70s. The following passage in a discussion of an exhibit including Spare's work in the summer of 1965 suggests some critics had hoped he would disappear into obscurity forever. The critic writes that the curator of the exhibit

"has resurrected an unknown English artist named Austin Osman Spare, who imitates etchings in pen and ink in the manner of Beardsley but really harks back to the macabre German romanticism. He tortured himself before the first war and would have inspired the surrealist movement had he been discovered early enough. He has come back in time to play a belated part in the revival of taste for art nouveau."[24]

Robert Ansell summarized Spare's artistic contributions as follows:

During his lifetime, Spare left critics unable to place his work comfortably. Ithell Colquhoun supported his claim to have been a proto-Surrealist and posthumously the critic Mario Amaya made the case for Spare as a Pop Artist. Typically, he was both of these - and neither. A superb figurative artist in the mystical tradition, Spare may be regarded as one of the last English Symbolists, following closely his great influence George Frederick Watts. The recurrent motifs of androgyny, death, masks, dreams, vampires, satyrs and religious themes, so typical of the art of the French and Belgian Symbolists, find full expression in Spare's early work, along with a desire to shock the bourgeois.[25]

Influence on Chaos Magic[edit]

Some of Spare's techniques, particularly the use of sigils and the creation of an "alphabet of desire" were adopted, adapted and popularized by Peter J. Carroll in the work Liber Null & Psychonaut.[26] Carroll and other writers such as Ray Sherwin are seen as key figures in the emergence of some of Spare's ideas and techniques as a part of a magical movement loosely referred to as Chaos magic.

A particular proponent of this argument is AOS, an artist who worked in a broadly asemic style.

Present his ideas.[edit]

The occult leanings of AOS and their effect on his philosophy. AOS as a proto-surrealist, working in the tradition of Bataille (Nietzsche, Crowley) while still outside it.

Kia[edit]

Regarding Spare's magical system, Kiaism, his terminology is unique and could not be traced back in other traditions. The introduction of original concepts like "Kia", "Ikkah", "Sikah" appear for the first time in Spare's first book Earth Inferno and remain conceptually consistent until The Focus of Life.

Beside the important influence of Kiaism on occultism in general, it represents no specific way for personal development and/or any sets of instructions but requires the person to devise his personal system of philosophy or magic.

The supreme state in Kiaism, Kia, is sketched: "The absolute freedom which being free is mighty enough to be "reality" and free at any time: therefore is not potential or manifest (except as it's instant possibility) by ideas of freedom or "means," but by the Ego being free to receive it, by being free of ideas about it and by not believing."[27]

However, Spare continually insists in various places that Kia is undefinable and any definition makes it more obscure.

Kiaism regards Belief and Desire as the great duality. In this system, Ego is a part of Self belonging to one Being while Self encircles the whole Being. Each "human" Being wills the desire. This desire imagines a new belief and belief by means of conceptualizing new concepts forms the Ego. Spare names these conceptions, "the ramifications of belief" which form different personalities for corresponding Ego. But the mentioned will is a partial one. The Will (emphasized by capitalizing) lies in the realm of Self - pertaining to Kia.[28]

On Self-Love[edit]

Self-Love is a mental state, mood or condition caused by the emotion of laughter becoming the principle that allows the Ego appreciation or universal association in permitting inclusion before conception.[29] So it is no narcissistic self-reflection of the glamours of the ego, rather, it is the void at the core of an identity which is freely able to move into any desired set of social relations, without becoming trapped or identified entirely within them. As the core of the sense of self is Self-love, rather than any label which encapsulates any particular set of behavior, beliefs and life-patterns, one attains a state of great freedom of movement and expression, without the need for self-definition.[30]

Explain his ideas.[edit]

Taking a core text of AOS' and 'exploding it' by criticism from Bataille. Interpreted as 'liturgy'.

notes[edit]

- ^ Semple, W. Gavin, ZOS-KIA, 1995, Fulgur Limited

- ^ Grant, Kenneth; Magical Revival, Austin Osman Spare and the Zos Kia Cultus

- ^ The most extensive source of biographical information available is Borough Satyr, The Life and Art of Austin Osman Spare, published by Fulgur Limited. In particular, the introduction by Robert Ansell contains much biographical information not available elsewhere. Much of the material in this section is taken from this source. However, it fails to mention Spare's eldest brother, one Phillip O. Spare. Birth, Marriage and Death Registers and indexes for the City of London show his birth in the third quarter of 1880. His death is registered in the second quarter of 1881 in the same registration district. Source: [1]

- ^ "Boy Artist At The R.A.", in The Daily Chronicle, Tuesday, May 3rd 1904

- ^ "Boy Artist At The R.A.", in The Daily Chronicle, Tuesday, May 3rd 1904

- ^ Keith Richmond, "Discord In The Garden Of Janus - Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare", in Austin Osman Spare: Artist - Occultist - Sensualist, Beskin Press, 1999. Richmond's research is the most complete account of the relationship between Spare and Crowley of which I am aware, and it is the only one that shows a responsible effort to document claims and cross-reference sources.

- ^ A document entitled "Oath of Probationer" from the Gerald Yorke Collection at the Warburg Institute indicates that Spare took the oath on July 10th, 1909.

- ^ Spare and Crowley apparently carried on a correspondence, though its extent is uncertain. At least two letters from Spare to Crowley exist in a collection of Crowley documents held at the library of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. One of these concerns Spare's lack of money for the purchase of his probationer's robe. See the study by Richmond already cited

- ^ The Equinox, Vol. 1, No. 2, London, September 1909. Spare contributed two drawings which were placed in an article on geomancy. He is also provided two diagrams for the same issue, numbered 33 (The Garden of Eden) and 51 (The Fall).

- ^ I've found no certain provenance for this photo, though one web caption indicates it was taken in 1913. Spare apparently also executed a portrait sketch of Crowley from memory in 1955, reproductions of which are extant.

- ^ Austin Osman Spare, The Book of Pleasure (Self-Love), The Psychology of Ecstasy, 1913

- ^ The only other available biographical detail relating to Spare's wife is a footnote in Borough Satyr, which states "Born in Shrewsbury on May 28th 1888, her birth certificate states her name as 'Eiley,' but throughout her life she was known as 'Eily,' and occasionally 'Lily'.

- ^ Borough Satyr, compiled and edited by Robert Ansell, Fulgur Limited, 2005, p6

- ^ Borough Satyr, compiled and edited by Robert Ansell, Fulgur Limited, 2005, p6

- ^ It has been asserted here and there online that Spare visited or was stationed in Egypt during World War I. I have found no evidence to support this claim. The most extensive information I have been able to find concerning Spare's military service is in a reminiscence by Haydn Mackay, apparently a transcript of a radio program that was broadcast, or intended for broadcast, shortly after Spare's death in 1956: "In 1918 I found Spare in the Army, he had been placed in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and with the rank of Sergeant, was employed in making drawings for the medical history of the war. Thus was acquired a collection of somewhat perfunctory, but technically impeccable drawings, now in the possession of the authorities. He worked in the solitude of a studio provided by the army, and the only military convention to which he had to conform was the wearing of the uniform; and I have never seen a queerer figure in a soldier’s garb. He wore the most dilapidated uniform I have seen outside a refuse dump, and it was worn in the most negligent manner conceivable. It is not surprising that on occasion he was held by the police as a rogue wearing unauthorised badges and uniform, and only released by them on a statement of his authenticity by his commanding officer."

- ^ Hannen Swaffer, "The Mystery of An Artist", in London Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1950 or 1951

- ^ Austin Osman Spare, The Anathema of Zos, 1927

- ^ Hannen Swaffer, "The Mystery of An Artist", in London Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1950 or 1951

- ^ Clifford Bax, "Sex in Art", in Ideas and People, 1936

- ^ Hannen Swaffer, "The Mystery of An Artist", in London Mystery Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1950 or 1951

- ^ Review of "A Book of Satyrs" (by Austin Osman Spare) in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 16, No. 81, (Dec., 1909), pp. 170-171

- ^ Review of "The Starlit Mire" (by James Bertram and F. Russel, with ten drawings by Austin Osman Spare), in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 19, No. 99 (Jun., 1911), pp. 177-177

- ^ Review of " The Book of Pleasure (Self-Love), the Psychology of Ecstasy" (by Austin Osman Spare) in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 26, No. 139, (Oct., 1914), pp. 38-39

- ^ "Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions", in The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 107, No. 747, (Jun., 1965), p. 330

- ^ Borough Satyr, The Life and Art of Austin Osman Spare, compiled and edited by Robert Ansell, Fulgur Limited, 2005, p19

- ^ Peter J. Carroll, Liber Null & Psychonaut, Weiser, 1987

- ^ Austin Osman Spare, The Book of Pleasure

- ^ Sepand, Collected Writings of Austin Osman Spare - Persian Translation, Translator's Forward, p 4

- ^ Spare, Austin Osman, The Book of Pleasure

- ^ Hine, Phil, Condensed Chaos, New Falcon, 1995, pp 127-128, ISBN 1-56184-117-X