User:Phaisit16207/sandbox 12

Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1949[a] | |||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: 中華民國國歌 "Chunghua Minkuo Kuoke" "National Anthem of the Republic of China" (1930–1949, last in Mainland China) For previous anthems, see Historical Chinese anthems. Flag anthem: 中華民國國旗歌 "Chunghua Minkuo Kuochike" "National Flag Anthem of the Republic of China" (1937–1949) | |||||||||||||||||

| National seal: 中華民國之璽 "Seal of the Republic of China" (1929–1949)  | |||||||||||||||||

Land controlled by the Republic of China (1946) shown in dark green; land claimed but uncontrolled shown in light green. | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Shanghai | ||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Standard Chinese | ||||||||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | |||||||||||||||||

| Official script | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | See Religion in China | ||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Chinese[1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | See the Government of the Republic of China

Details

| ||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||

• 1912 | Sun Yat-sen (first, provisional) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1949–1950 | Li Zongren (last in Mainland China, acting) | ||||||||||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||||||||||

• 1912 | Tang Shaoyi (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1949 | He Yingqin (last in Mainland China) | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||||||||

| Control Yuan | |||||||||||||||||

| Legislative Yuan | |||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Xinhai Revolution begins | 10 October 1911[f] | ||||||||||||||||

• Sun Yat-sen proclaimed the Republic of China | 1 January 1912 | ||||||||||||||||

• Admitted to the League of Nations | 10 January 1920 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1926–1928 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1927–1936, 1945–1949[g] | |||||||||||||||||

| 1937–1945[h] | |||||||||||||||||

• Founder of the United Nations | 24 October 1945 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25 December 1947 | |||||||||||||||||

• Chinese Civil War; Mao Zedong proclaimed the PRC | 1 October 1949 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 December 1949[a] | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 May 1950[i] | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1912 | 11,364,389 km2 (4,387,815 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1946 | 9,665,354 km2 (3,731,814 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 to +8:30 (Kunlun to Changpai Standard Times) | ||||||||||||||||

| Drives on | Right[j] | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| History of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

The Republic of China (ROC),[k] or simply China,[l] began as a sovereign state in mainland China[a] on 1 January 1912 following the 1911 Revolution, which overthrew the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and ended China's imperial history. From 1927, the Kuomintang (KMT) reunified the country and ruled it as a one-party state ("Dang Guo") and made Nanjing the national capital. In 1949, the KMT-led government was defeated in the Chinese Civil War and lost control of the mainland to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP established the People's Republic of China (PRC) while the ROC was forced to retreat to Taiwan and retains control over the "Taiwan Area"; the political status of Taiwan remains in dispute to this day.

The republic was proclaimed on 1 January 1912, ensuing the 1911 Revolution that overthrew the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty in Chinese history. Sun Yat-sen, the ROC's founder and the first provisional president, served only briefly before handing over the presidency to Yuan Shikai, the leader of the Beiyang Army. Yuan later became authoritarian and used his military power to control the administration, which became known as the "Beiyang government" (or the First Republic of China). Yuan even attempted to restore the Chinese monarchy. Following his death, the country fragmented between the various local commanders of the Beiyang Army, leading to the period known as the Warlord Era. The Kuomintang (Nationalists), under Sun's leadership, was able to establish a rival national government in Canton, owing to Soviet support; subsequently, they formed the First United Front with the Chinese Communist Party. Sun's death in 1925 led to a power struggle, leading to General Chiang Kai-shek becoming Chairman of the Kuomintang. Chiang led a successful "Northern Expedition" with strategic alliances with warlords and Soviet support. The nationalist alliance with the communists ended up by the purge of the communists from the KMT in 1927, and the last major independent warlord pledged allegiance to the Nationalist government in Nanjing a year later. The Nanjing-based nationalist government nominally brought China to a unified one-party state rule under the Kuomintang, which can also be referred as the Second Republic of China.[2]

Despite relative prosperity during the following ten years under Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist rule was still destabilised by the civil war, revolts by the KMT's warlord allies, and steady territorial encroachments by Japan. The CCP gradually rebuilt its strength by focusing on organising peasants in the countryside. Warlords' resentments on Chiang's attempts to unify their clique led to devastating uprisings, most significantly the Central Plains War. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 triggered conflict between China and Japan, which escalated in 1937 when the Japanese totally penetrated China, leading to the devastration of both China's materiel and of China's population. In the aftermath of the Second World War in 1945, Taiwan was placed under the Chinese adminstration. The civil war resumed between the Nationalists and the Communists, with the Communist People's Liberation Army, under Mao Zedong, winning the better-armed National Revolutionary Army, ultimately resulting in the government's retreat to Taiwan. In October 1949, the CCP established of the People's Republic of China, with nationalist remnents hanging in Mainland China until 1951. The Kuomintang had dominated ROC's politics for seventy-two years and for fifty-four years on the island of Taiwan until they lost the presidential election in 2000 to the Taiwanese nationalist Democratic Progressive Party.

The ROC was a founding member of the League of Nations and later the United Nations (including its Security Council seat) where it maintained until 1971, when the People's Republic of China took over its membership. It was also a member of the Universal Postal Union and the International Olympic Committee. At a population of 541 million in 1949, it was the world's most populous country. Covering 11.4 million square kilometres (4.4 million square miles) of its previously claimed territory,[3] it consisted of 35 provinces, 1 special administrative region, 2 regions, 12 special municipalities, 14 leagues, and 4 special banners.

Names

[edit]During the mainland period, the country was known in English as "China" or the "Republic of China". Internally, Zhongguo (Chinese: 中國; lit. 'middle country'), Zhonghua or Jung-hwa (Chinese: 中華; lit. 'middle and beautiful'), or Minguo (Chinese: 民國; lit. 'people's country') were used as short forms of the official country name Zhonghua Minguo (Chinese: 中華民國; lit. 'Chinese people's state') in Chinese.[4][5][6] Both "Beiyang government" (from 1912 to 1928), and "Nationalist government" (from 1928 to 1949) used the name "Republic of China" as their official name.[7] The People's Republic of China (PRC), which rules mainland China today, considers ROC as a country that ceased to exist since 1949; thus, the history of ROC before 1949 is often referred to as Republican Era (simplified Chinese: 民国时期; traditional Chinese: 民國時期) of China.[8][9][10][11] The ROC, now based in Taiwan, today considers itself a continuation of the country, thus referring to the period of its mainland governance as the Mainland Period (traditional Chinese: 大陸時期; simplified Chinese: 大陆时期) of the Republic of China in Taiwan.[12]

Significance of the name

[edit]The country's official Chinese name Chunghwa Minkuo, stemmed from the party manifesto of Tongmenghui in 1905, which says the four goals of the Chinese revolution was "to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive Chunghwa, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people. (Chinese: 驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權; pinyin: Qūchú dálǔ, huīfù Zhōnghuá, chuànglì mínguó, píngjūn dì quán)." The convener of Tongmenghui and Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen proposed the name Chunghwa Minkuo as the assumed name of the new country when the revolution succeeded. After the Xinhai revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty in 1911–12, Sun further explained the meaning of the country's Chinese name in detail in 1916:

| “ | Do you know the meaning of Chunghwa Minkuo? Why don't we call it Chunghwa Konghekuo (Chinese: 中華共和國; pinyin: Zhōnghuá Gònghéguó; lit. 'Chinese republic')[m] but rather Chunghwa Minkuo (Chinese: 中華民國; pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó; lit. 'Chinese people's state')? The meaning of the Chinese character "Min" (Chinese: 民; pinyin: Mín; lit. 'people') is the result of my decade-long research. Republics in Europe and the Americas were founded before this state. With our state founded in the 20th century, we shall have the spirit of innovation but not be satisfied with mimicking those founded in the 18th and 19th centuries. A republic as a representative form of government is universal across the world. For example, despite the dichotomy of the nobles and the slaves, Greece calls its state a republican dictatorship. While the United States, with its fourteen states, sets an example of large-scale democracy, Switzerland almost practices pure democracy. As our state transforms from absolutism to representative democracy, how can we fail to innovate and fall behind other nations? Our nation should thrive to see the world, to see the brightness of democracy, to better pursue fuller democracy on our soils. Under the flag of representative systems, our people only have the right to be politically represented. If we are to pursue democracy, we will possess the rights of initiatives, nullification, and recall. But such people's rights are not appropriate to be exercised on a provincial basis but rather be on a county-wide basis. Local finance should be autonomous, while the central government's finance is funded by localities. All kinds of the rest the industries should avoid the shortcomings of American-styled trust monopolies and should be controlled by the central government. If so, within a few years, a grave, bright Republic of China will be among the top republics in the world. | ” |

| — Sun Yat-Sen | ||

On 20 October 1923, Sun again stressed that Chunghwa Minkuo means a state "of the people".[13]

Relevance in Taiwan politics

[edit]The Taiwanese politician Mei Feng criticised the official English name of the state, "Republic of China," which fails to translate the Chinese character "Min" (Chinese: 民; pinyin: people) according to Sun Yat-sen's original interpretations, and stated the name should instead be translated as "the People's Republic of China." That would be the same as the current official name of mainland China under communist rule.[14] To avoid confusion, the ROC government in Taiwan began to put "Taiwan" next to its official name in 2005.[15]

History

[edit]Overview

[edit]A republic was formally established on 1 January 1912 following the Xinhai Revolution, which itself began with the Wuchang uprising on 10 October 1911, successfully overthrowing the Qing dynasty and ending over two thousand years of imperial rule in China.[16] From its founding until 1949, the republic was based on mainland China. Central authority waxed and waned in response to warlordism (1915–1928), a Japanese invasion (1937–1945), and a full-scale civil war (1927–1949), with central authority strongest during the Nanjing Decade (1927–1937), when most of China came under the control of the authoritarian, one-party military dictatorship of the Kuomintang (KMT).[17]

In 1945, at the end of World War II, the Empire of Japan surrendered control of Taiwan and its island groups to the Allies; and Taiwan was placed under the Republic of China's administrative control. The communist takeover of mainland China in 1949, after the Chinese Civil War, left the ruling Kuomintang with control over only Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and other minor islands. With the loss of the mainland, the ROC government retreated to Taiwan and the KMT declared Taipei the provisional capital.[18] Meanwhile, the CCP took over all of mainland China[19][20] and founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing.

Founding and initial Beiyang rule (1912–1916)

[edit]Background

[edit]

In the late Qing dynasty, the ruling dynasty of China, was suffered the instability from both internal rebellion and foreign imperialism, and social unrests.[21] The Boxer Rebellion led the Eight-Nation Alliance force to launch a war of aggression against China, forcing the Qing government to sign the Xinchou Treaty. Some Chinese enlightened individuals and oversea students established some revolutionary organisations.[22] In 1908, the Qing Government annunciate Principles of the Imperial Constitution and announced that constitutionality will be implemented in ten years to deal with calls for reform. The result, however, was a huge disappointment for the constitutionalists, and leading the revolution became popular.[23][24]

The Chinese Tongmenghui (United League), an underground movement founded by Sun Yat-sen, began to take action by launching the Huanghuagang uprising at Canton in 27 April 1911, but was suppressed by the Qing Army. On 17 June, the Sichuan Railway Protection Comrades Association was founded and launched the Railway Protection Movement led by constitutionalists.

1911 Revolution and the overthrown of monarchy

[edit]The Gongjinhui, with the Literary Society, launched the Wuchang Uprising against the Qing government on 10 October 1911, leading to the establishment of the Military Government of the Republic of China, which is now celebrated annually as the ROC's national day, also known as "Double Ten Day". Subsequently, 15 provinces in China successively declared independence from the Qing government, forming the nationwide 1911 Revolution.[25] The Hubei Army Governor's Office was established on the follow day in Wuchang, Hubei,[26] and on 17 November, a joint meeting of provincial governor's offices recognised the Hubei Military Government as the Central Military Government of the Republic of China. The first constitutional law of the Republic of China, the Organisational Outline of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, was passed on 3 November. The revolutionaries organised the Central Provisional Government, while they negotiated the Qing Prime Minister, Yuan Shikai, who agreed to would be elected as the president of the provisional government if he forced the Qing emperor to abdicate. Sun, who had been actively promoting revolution from his bases in exile, was returned to China and on 29 December, he was elected interim president by the Nanjing assembly in Jiangning Mansion, Jiangsu,[27] which consisted of representatives from seventeen provinces. Jebtsundamba Khutuktu established the Bogd Khanate of Mongolia, and declared Outer Mongolia independence from the Qing rule on the same day. The Lhasa turmoil broke out in Tibet, and Qing officials and garrisons were expelled, the 13th Dalai Lama, who had been exiled in British Raj for many years, later returned to Lhasa and regained power in Tibet.

Establishment and Yuan's dictatorship

[edit]

On 1 January 1912, the Provisional Government was formally established in Nanjing, Sun Yat-sen was officially inaugurated and pledged "to overthrow the despotic government led by the Manchu, consolidate the Republic of China and plan for the welfare of the people",[28] Sun Yat-sen also proposed the "Five Offers" on behalf of the Provisional Government on 18 January.[29] Sun's new government lacked military strength. As a compromise, he negotiated with Yuan Shikai the commander of the Beiyang Army, promising Yuan the presidency of the republic if he were to remove the Qing emperor by force. Yuan agreed to the deal.[30] On 12 February 1912, regent Empress Dowager Longyu signed the abdication decree on behalf of the Xuantong Emperor, ending several millennia of Chinese monarchical rule.[31] Yuan was elected provisional president of the ROC in on 15 February 1912, as Sun Yat-sen kept his promise, he resigned to senate two days earlier.[21][32] The senate passed the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China on 8 March, and he sworn in two days later.[33] In the first parliamentary election at the end of the year, the Kuomintang, led by Song Jiaoren, won a majority of seats both in the Senate and the House of Representatives, by fashioning his party's program to appeal to the gentry, landowners, and merchants.[34]

Song Jiaoren, who was about to become Prime Minister, was assassinated on 20 March 1913, at the behest of Yuan Shikai, leaving him and other Beiyang warlords held the power.[35] He ruled by military power and ignored the republican institutions established by his predecessor, threatening to execute Senate members who disagreed with his decisions. Sun Yat-sen directed several southern provinces to launch a second revolution against him, but failed due to the assassination pf Song and massive loan that resulted in the loss of power and humiliation of the country.[36] Yuan was elected as the first president of the republic on 6 October 1914, Congress passed the Tiantan Constitution and adopted a cabinet system to restrict his power. He soon postponed the ruling Kuomintang party for participating in the second revolution, banned "secret organizations" (which implicitly included the KMT), and ordered the dissolution of Congress.[34][37] In 1914, Yuan ordered the National Assembly to amend the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China and change the cabinet system to a presidential system, He also announced the country's name would be changed to the Empire of China in December 1915.[34] Cai E and Tang Jiyao, generals of the Yunnan province, soon declared independence and organised the National Protector Army to overthrown Yuan. In 1916, Yuan Shikai renounced the imperial system and sought re-election as president, but was rejected by the National Guard Army. Yuan died of illness on 6 June.[38][39]

Warlord Era (1916–1927)

[edit]Yuan's changes to government caused many provinces to declare independence and become warlord states. Increasingly unpopular and deserted by his supporters, Yuan abdicated in 1916 and died of natural causes shortly thereafter.[38][39] The central government lacked the strength to govern various provinces, China subsequently experienced a period of warlord seperatism. The main forces of the Beiyang Government, including Zhang Zuolin of the Fengtian clique, Duan Qirui of the Anhui clique, and Cao Kun of the Zhili clique, fought for control of the government many times.[40][41] Other warlords included Yan Xishan's Shanxi clique, Feng Yuxiang's Northwest Army, Tang Jiyao's Yunnan clique, and Lu Rongting's old Guangxi clique. Sun, having been forced into exile, returned to Guangdong in 1917 with the help of warlords, and cooperated with the Cantonese warlords to establish a separate military government of the Republic of China, which was the rival government to the Beiyang Government in Peking, in Panyu county, having re-established the KMT in October 1919.

Meanwhile, the Beiyang government struggled to hold onto power, and an open and wide-ranging debate evolved regarding how China should confront the West. In 1919, a student protest against the government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles,[42] considered unfair by Chinese intellectuals, led to the May Fourth movement, whose demonstrations were against the danger of spreading Western influence replacing Chinese culture.[42] It was in this intellectual climate that the influence of Marxism spread and became popular, leading to the founding of the CCP in 1921.[43]

After Sun's death in March 1925, Chiang Kai-shek became the leader of the Kuomintang. In 1926, Chiang led the Northern Expedition with the intention of defeating the Beiyang warlords and unifying the country. Chiang received the help of the Soviet Union and the CCP. However, he soon dismissed his Soviet advisers, being convinced that they wanted to get rid of the KMT and take control.[44] Chiang decided to purge the Communists, killing thousands of them. At the same time, other violent conflicts were taking place in China: in the South, where the CCP had superior numbers, Nationalist supporters were being massacred. Such events eventually led to the Chinese Civil War between the Nationalists and Communists.

Nationalist rule (1927–1931)

[edit]Nanjing decade

[edit]

Chiang Kai-shek pushed the CCP into the interior and established a government, with Nanjing as its capital, in 1927.[45] By 1928, Chiang's army overthrew the Beiyang government and unified the entire nation, at least nominally, beginning the so-called Nanjing decade.[46]

Sun Yat-sen envisioned three phases for the KMT rebuilding of China – military rule and violent reunification; political tutelage; and finally a constitutional democracy.[47] In 1930, after seizing power and reunifying China by force, the "tutelage" phase started with the promulgation of a provisional constitution.[48] In an attempt to distant themselves from the Soviets, the Nationalist Government sought assistance from Germany. Chiang Kai-chek was influenced by European fascist movements, and launched the Blue shirts and the New Life Movement in conscious imitation of them.[49][50] Several major government institutions were founded during this period, including the Academia Sinica and the Central Bank of China. In 1932, China sent its first team to the Olympic Games. Campaigns were mounted and laws passed to promote the rights of women. In the 1931 Civil Code, women were given equal inheritance rights, banned forced marriage and gave women the right to control their own money and initiate divorce.[51] No nationally unified women's movement could organise until China was unified under the Kuomintang Government in Nanjing in 1928; women's suffrage was finally included in the new Constitution of 1936, although the constitution was not implemented until 1947.[52] Addressing social problems, especially in remote villages, was aided by improved communications. The Rural Reconstruction Movement was one of many that took advantage of the new freedom to raise social consciousness.[citation needed] The Nationalist government published a draft constitution on 5 May 1936.[53]

Local uprising and reforms

[edit]Continual wars plagued the government. Those in the western border regions included the Kumul Rebellion, the Sino-Tibetan War, and the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang. Large areas of China proper remained under the semi-autonomous rule of local warlords such as Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan, provincial military leaders, or warlord coalitions.[46] Nationalist rule was strongest in the eastern regions around the capital Nanjing. The Central Plains War in 1930, the Japanese aggression in 1931, and the Red Army's Long March in 1934 led to more power for the central government, but there continued to be foot-dragging and even outright defiance, as in the Fujian Rebellion of 1933–34.[citation needed]

Reformers and critics pushed for democracy and human rights, but the task seemed difficult if not impossible. The nation was at war and divided between Communists and Nationalists. Corruption and lack of direction hindered reforms. Chiang told the State Council: "Our organization becomes worse and worse... many staff members just sit at their desks and gaze into space, others read newspapers and still others sleep."[54]

Conflict with Japan and World War II (1931–1945)

[edit]Outbreak in the East

[edit]

Few Chinese had any illusions about Japanese desires on China. Hungry for raw materials and pressed by a growing population, Japan initiated the seizure of Manchuria in September 1931 and established the ex-Qing emperor Puyi as head of the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932. The loss of Manchuria, and its potential for industrial development and war industries, was a blow to the Kuomintang economy.[55][56] The League of Nations, established at the end of World War I, was unable to act in the face of Japanese defiance.[57]

The Japanese began to push south of the Great Wall into northern China and the coastal provinces.[58][59] Chinese fury against Japan was predictable, but anger was also directed against Chiang and the Nanjing government, which at the time was more preoccupied with anti-Communist extermination campaigns than with resisting the Japanese invaders. The importance of "internal unity before external danger" was forcefully brought home in December 1936, when Chiang Kai-shek, in an event now known as the Xi'an Incident, was kidnapped by Zhang Xueliang and forced to ally with the Communists against the Japanese in the Second Kuomintang-CCP United Front.[60]

Resuming conquest of China

[edit]Chinese resistance stiffened after 7 July 1937, when a clash occurred between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Peiping (Later Beijing) near the Marco Polo Bridge.[55][61][62] This skirmish led to open, although undeclared, warfare between China and Japan. Shanghai fell after a three-month battle during which Japan suffered extensive casualties in both its army and navy. The capital, Nanjing, fell in December 1937,[63] which was followed by mass murders and rapes known as the Nanjing Massacre. The national capital was briefly at Wuhan, then removed in an epic retreat to Chongqing (Chungking), the seat of government until 1945.[64] In 1940, the Japanese set up the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime, with its capital in Nanjing, which proclaimed itself the legitimate "Republic of China" in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek's government, although its claims were significantly hampered due to its being a puppet state controlling limited amounts of territory.

The United Front between the Kuomintang and the CCP had salutary effects for the beleaguered CCP, despite Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions and the rich Yangtze River Valley in central China. After 1940, conflicts between the Kuomintang and Communists became more frequent in the areas not under Japanese control.[65] The Communists expanded their influence wherever opportunities presented themselves through mass organizations, administrative reforms and the land- and tax-reform measures favoring the peasants and, the spread of their organizational network, while the Kuomintang attempted to neutralise the spread of Communist influence. Meanwhile, northern China was infiltrated politically by Japanese politicians in Manchukuo using facilities such as the Wei Huang Gong.

World War II

[edit]

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, China formally declared war on Japan three days later.[66] After its entry into the Pacific War during World War II, the United States became increasingly involved in Chinese affairs.[67] As an ally, it embarked in late 1941 on a program of massive military and financial aid to the hard-pressed Nationalist Government. In January 1943, both the United States and the United Kingdom led the way in revising their unequal treaties with China from the past.[n][68] Within a few months a new agreement was signed between the United States and the Republic of China for the stationing of American troops in China as part of the common war effort against Japan. The United States sought unsuccessfully to reconcile the rival Kuomintang and Communists, to make for a more effective anti-Japanese war effort. In December 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1880s, and subsequent laws, enacted by the United States Congress to restrict Chinese immigration into the United States were repealed. The wartime policy of the United States was meant to help China become a strong ally and a stabilizing force in postwar East Asia. During the war, China was one of the Big Four Allies of the Second World War and later one of the Four Policemen, which was a precursor to China having a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.[69]

In August 1945, with American help, Nationalist troops moved to take the Japanese surrender in North China. The Soviet Union—encouraged to invade Manchuria to hasten the end of the war and allowed a Soviet sphere of influence there as agreed to at the Yalta Conference in February 1945—dismantled and removed more than half the industrial equipment left there by the Japanese. Although the Chinese had not been present at Yalta, they had been consulted and had agreed to have the Soviets enter the war, in the belief that the Soviet Union would deal only with the Kuomintang government. However, the Soviet presence in northeast China enabled the Communists to arm themselves with equipment surrendered by the withdrawing Japanese army.

Civil War and Retreat to Taiwan (1945–1949)

[edit]Post-War and Civil War re-emerged

[edit]In 1945, after the end of the war, the Nationalist Government moved back to Nanjing. The Republic of China emerged from the war nominally a great military power but actually a nation economically prostrate and on the verge of all-out civil war. The problems of rehabilitating the formerly Japanese-occupied areas and of reconstructing the nation from the ravages of a protracted war were staggering. The economy deteriorated, sapped by the military demands of foreign war and internal strife, by spiraling inflation, and by Nationalist profiteering, speculation, and hoarding. Starvation came in the wake of the war, and millions were rendered homeless by floods and unsettled conditions in many parts of the country.

On 25 October 1945, following the surrender of Japan, the administration of Taiwan and Penghu Islands were handed over from Japan to China.[70] After the end of the war, United States Marines were used to hold Peiping and Tientsin against a possible Soviet incursion, and logistic support was given to Kuomintang forces in north and northeast China.[71] To further this end, on 30 September 1945 the 1st Marine Division, charged with maintaining security in the areas of the Shandong Peninsula and the eastern Hebei, arrived in China.[72]

In January 1946, through the mediation of the United States, a military truce between the Kuomintang and the Communists was arranged, but battles soon resumed.[73] Public opinion of the administrative incompetence of the Nationalist government was incited by the Communists during the nationwide student protest against the mishandling of the Shen Chong rape case in early 1947 and during another national protest against monetary reforms later that year.[74] The United States—realizing that no American efforts short of large-scale armed intervention could stop the coming war—withdrew Gen. George Marshall's American mission.[75] Thereafter, the Chinese Civil War became more widespread; battles raged not only for territories but also for the allegiance of sections of the population.[76] The United States aided the Nationalists with massive economic loans and weapons but no combat support.[77]

Collapse in Mainland and flee to Taiwan

[edit]

Belatedly, the Republic of China government sought to enlist popular support through internal reforms. However, the effort was in vain, because of rampant government corruption and the accompanying political and economic chaos. By late 1948 the Kuomintang position was bleak.[78] The demoralised and undisciplined National Revolutionary Army proved to be no match for the Communists' motivated and disciplined People's Liberation Army.[79] The Communists were well established in the north and northeast.[80] Although the Kuomintang had an advantage in numbers of men and weapons, controlled a much larger territory and population than their adversaries, and enjoyed considerable international support, they were exhausted by the long war with Japan and in-fighting among various generals. They were also losing the propaganda war to the Communists, with a population weary of Kuomintang corruption and yearning for peace.[81]

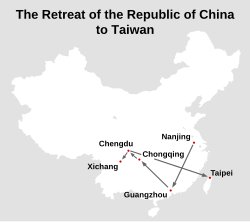

In January 1949, Peiping was taken by the Communists without a fight, and its name changed back to Beijing.[82][83] Following the capture of Nanjing on 23 April, major cities passed from Kuomintang to Communist control with minimal resistance, through November.[82][84] In most cases the surrounding countryside and small towns had come under Communist influence long before the cities.[85] Finally, on 1 October 1949, Communists led by Mao Zedong founded the People's Republic of China.[86] Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law in May 1949,[87] whilst a few hundred thousand Nationalist troops and two million refugees, predominantly from the government and business community, fled from mainland China to Taiwan.[88][89] There remained in China itself only isolated pockets of resistance. The seat of government, after the fall of Nanking, was moved to Kwangchow, before to its wartime capital, Chungking, and lastly on mainland, Chengtu, with some moving to Sichang. On 7 December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei, Taiwan, the temporary capital of the Republic of China, with Chengtu falling to the Communists on 27 December.

During the Chinese Civil War both the Nationalists and Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants killed by both sides.[90] Benjamin Valentino has estimated atrocities in the civil war resulted in the death of between 1.8 million and 3.5 million people between 1927 and 1949, including deaths from forced conscription and massacres.[91]

Geography

[edit]...

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The state did not cease to exist in 1949. The government was relocated from Nanjing (Nanking) in Mainland China to Taipei of Taiwan, where it continues to be based to this day. Cite error: The named reference "existence" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Nanjing was still marked as the de jure capital on maps published by the Ministry of the Interior after 1949, until publication was suspended in 1998.

- ^ The Republic of China was proclaimed in Nanjing on 1 January, and its capital was moved to Beijing on March 10 of the same year.

- ^ From 23 April 1949, the government was evacuated to Guangzhou, Chongqing and Chengdu in the Mainland before declaring Taipei as its temporary capital on 7 December 1949. Chengdu was captured on 27 December.

- ^ As wartime provisional capital during the Second Sino-Japanese War after the fall of Nanjing.

- ^ From Wuchang Uprising started on 10 October 1911, until the last monarch of the Qing dynasty, Xuantong Emperor abdicated, formally ending the Qing dynasty, on 12 February 1912.

- ^ Chinese Communist Revolution.

- ^ From Marco Polo Bridge Incident started on 7 July 1937, until the Surrender of Japan, which ended World War II, on 2 September 1945.

- ^ Independent Tibet was annexed by the PRC on 23 May 1951.

- ^ Left hand drive until 1946.

- ^ Chinese: 中華民國

- Postal: Chunghwa Minkuo

- Pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínguó

- Wade–Giles: Chung¹-hua² Min²-kuo²

- Jyutping: Zung¹waa⁴ Man⁴gwok³

- ^ 中國

- Postal: Chungkuo

- Pinyin: Zhōngguó

- Wade–Giles: Chung¹-kuo²

- Jyutping: Zung¹gwok³

- ^ The Chinese name was also used by the Fujian People's Government in 1933.

- ^ See Sino-U.S. Treaty for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China and Sino-British Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dreyer 2003.

- ^ Wang, Dong (1 October 2005). China's Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-5297-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Yearbook of the 94th Year of the Republic of China: Part One, General Introduction, Chapter Two, Land, Section Two, Mainland Area

- ^ External Declaration of the Provisional President of the Republic of China

- ^ The age known as the "Golden Decade of the Republic of China" by the West

- ^ 中华民国纪年也称“民国纪年”。

- ^ Wright (2018).

- ^ Exploring Chinese History :: Database Catalog :: Biographical Database :: Republican Era- (1912–1949).

- ^ Catalog and scholar database of the Republican period (1911–1949).

- ^ Enlightenment and Critical Enlightenment during the Republic.

- ^ Full-text database of periodicals during the Republic (1911–1949).

- ^ Joachim, Martin D. (1993). Languages of the World: Cataloging Issues and Problems. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781560245209. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ The origin and significance of the name of the Republic of China.

- ^ Republic of China should be translated as "PRC".

- ^ BBC in Chinese 2005.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

cuhkwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Roy 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ BBC News 2000

- ^ China: U.S. policy since 1945. Congressional Quarterly. 1980. ISBN 0-87187-188-2.

the city of Taipei became the temporary capital of the Republic of China

- ^ Introduction to Sovereignty: A Case Study of Taiwan (Report). Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. 2004. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ a b "The Chinese Revolution of 1911". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Gongquan, Xiao (1979). A History of Chinese Political Thought. Vol. 1. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03116-3.

- ^ Dulles, Foster R. (1972). American policy toward Communist China, 1949-1969. Crowell. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-690-07612-7.

- ^ Trocki, Carl (1999). Opium, Empire and the Global Political Economy: A Study of the Asian Opium Trade 1750-1950. Routledge. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-415-19918-6.

- ^ Hsü 1970, p. 557.

- ^ Hsü 1970, p. 556.

- ^ "Sun Yat Sen elected president of new Republic of China". Shanghai: United Press International. 29 December 1911. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 123

- ^ Hsü 1970, p. 561

- ^ Hsü 1970, pp. 472–474

- ^ "The abdication decree of Emperor Puyi (1912)". alphahistory.com. 4 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Fenby 2009, pp. 123–125

- ^ Hsü 1970, p. 563

- ^ a b c Fenby 2009, p. 131

- ^ Jonathan Fenby, "The silencing of Song." History Today (March 2013) 63#3 pp 5–7.

- ^ Fenby 2009, pp. 131, 134.

- ^ Jeans 1997, p. 134.

- ^ a b Fenby 2009, pp. 136–138

- ^ a b Meyer, Wittebols & Parssinen 2002, pp. 54–56

- ^ Pye 1971, p. 23.

- ^ Zarrow 2006, p. 84.

- ^ a b Meyer 1994, p. 274.

- ^ Guillermaz 1972, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Fenby 2009

- ^ In Minguo 16, the National Government declared Nanjing as the capital, and today Taipei City is the seat of our country's central government.

- ^ a b Kucha & Llewellyn 2019

- ^ Fung 2000, p. 30

- ^ Chen & Myers 1994, p. 102 "After the 1930 mutiny ended, Chiang accepted the suggestion of Wang Ching-wei, Yen Hsi-shan, and Feng Yü-hsiang that a provisional constitution for the political tutelage period be drafted."

- ^ Eastman 2021.

- ^ Payne 2021, p. 337.

- ^ Hershatter, G. (2018). Women and China's Revolutions. US: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- ^ Spakowski & Milwertz 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Zhiren 1984.

- ^ Fung 2000, p. 5 "Nationalist disunity, political instability, civil strife, the communist challenge, the autocracy of Chiang Kai-shek, the ascendancy of the military, the escalating Japanese threat, and the "crisis of democracy" in Italy, Germany, Poland, and Spain, all contributed to a freezing of democracy by the Nationalist leadership."

- ^ a b Ray et al. 2017

- ^ Yen Shen 2014, p. 124.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 236.

- ^ Whitehurst 2020, p. 100.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 246.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 274.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 136.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 142.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 146.

- ^ Fenby 2009, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 157.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 200.

- ^ Hsiung & Levine 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Urquhart 1998.

- ^ Howe 2016, p. 71.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 328.

- ^ Jessup 1989.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 10.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 70.

- ^ Melby 1968, p. 168.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Melby 1968, p. 248.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 138.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 149.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 88.

- ^ a b Melby 1968, p. 295.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Lary 2015, p. 178.

- ^ Lary 2015, pp. 3, 84.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 349.

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 347.

- ^ Malaspina 2015, p. 57.

- ^ Rigger 2011, p. 68.

- ^ Rummel, Rudolph (1994), Death by Government.

- ^ Valentino 2013, p. 88.

Sources

[edit]- Boorman, Howard, et al., eds.,Biographical Dictionary of Republican China. (New York: Columbia University Press, 4 vols, 1967–1971). 600 articles. Available online at Internet Archive.

- Botjer, George F. (1979). A short history of Nationalist China, 1919–1949. Putnam. p. 180. ISBN 9780399123825. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Chen, Lifu; Myers, Ramon Hawley (1994). Hsu-hsin Chang, Ramon Hawley Myers (ed.). The storm clouds clear over China: the memoir of Chʻen Li-fu, 1900–1993. Hoover Press. ISBN 0-8179-9272-3.

- Eastman, Lloyd (2021). "Fascism in Kuomintang China: The Blue Shirts". The China Quarterly (49). Cambridge University Press: 1–31. JSTOR 652110. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Fenby, Jonathan (2009). The Penguin history of modern China : the fall and rise of a great power, 1850-2009. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-102009-9.

- Fung, Edmund S. K. (2000). In Search of Chinese Democracy: Civil Opposition in Nationalist China, 1929-1949. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521771242. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- Guillermaz, Jacques (1972). A History of the Chinese Communist Party 1921–1949. Taylor & Francis. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Hsiung, James Chieh; Levine, Steven I., eds. (2016) [1992]. China's bitter victory : the war with Japan, 1937-1945. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3632-4.

- Howe, Brendan M. (2016). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781317077404. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Hsü, Immanuel C.Y. (1970). The Rise of Modern China (1995 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195087208.

- Jeans, Roger B. (1997). Democracy and socialism in Republican China: The Politics of Zhang Junmai (Carsun Chang), 1906-1941. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-8707-7.

- Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945–1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- Jowett, Philip. (2013) China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894–1949 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013).

- Lary, Diana (2015). China's Civil War: a Social History, 1945-1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05467-7.

- Leung, Edwin Pak-wah. Historical Dictionary of Revolutionary China, 1839–1976 (1992) online free to borrow

- Leung, Edwin Pak-wah. Political Leaders of Modern China: A Biographical Dictionary (2002)

- Li, Xiaobing. (2007) A History of the Modern Chinese Army excerpt Archived 10 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Li, Xiaobing. (2012) China at War: An Encyclopedia excerpt

- Malaspina, Ann (2015). Mao Zedong and the Chinese Revolution. Enslow Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7660-7293-0.

- Melby, John F. (1968). The Mandate of Heaven: Record of a civil war; China 1945-49. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-1520-4.

- Meyer, Kathryn; Wittebols, James H.; Parssinen, Terry (2002). Webs of Smoke. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-2003-X. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- Meyer, Milton W. (1994). China: A Concise History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-7953-9.

- Mitter, Rana (2004). A Bitter Revolution: China's Struggle with the Modern World. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192803417.

- Payne, Stanley (2021). A History of Fascism 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299148744. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Pye, Lucian W. (1971). Warlord politics: Conflict and coalition in the modernization of Republican China. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-28180-9.

- Rigger, Shelley (2011). "Looking Toward the Future in the Taiwan Strait: Generational Politics in Taiwan". The SAIS Review of International Affairs. 2 (31): 65–78. JSTOR 27000254 – via JSTOR.

- Roy, Denny (2004). Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8805-2.

- Sheridan, James E. (1975). China in Disintegration : The Republican Era in Chinese History, 1912–1949. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0029286107.

- Spakowski, Nicola; Milwertz, Cecilia Nathansen (2006). Women and Gender in Chinese Studies. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8258-9304-0.

- Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674033382.

- Urquhart, Brian (16 July 1998). Looking for the Sheriff. New York Review of Books.

- Valentino, Benjamin A. (2013). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6717-2.

- van de Ven, Hans (2017). China at War: Triumph and Tragedy in the Emergence of the New China, 1937–1952. London: Profile Books Limited. ISBN 9781781251942. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Vogel, Ezra F. China and Japan: Facing History (2019) excerpt Archived 9 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Westad, Odd Arne. Restless Empire: China and the World since 1750 (2012) Online free to borrow

- Whitehurst, George William (2020). The China Incident: Igniting the Second Sino-Japanese War. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-4135-5.

- Wilbur, Clarence Martin. Sun Yat-sen, frustrated patriot (Columbia University Press, 1976), a major scholarly biography online

- Yen Shen, Grace (2014). Unearthing the Nation: Modern Geology and Nationalism in Republican China. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-09054-2.

- Zarrow, Peter (2006). China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-21977-3.

- Zhiren, Jing (1984). Zhōngguó Xiànfǎ Shǐ 中国立宪史 [History of Chinese Constutitionalism] (in Chinese). Taipei: Lianjing Chubanshe.

Online

[edit]- Dreyer, June Teufel (17 July 2003). The Evolution of a Taiwanese National Identity. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Exploring Chinese History :: Database Catalog :: Biographical Database :: Republican Era- (1912–1949)". Ibiblio. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Feng, Mei. "Zhōnghuá mínguó yīng yì wèi `PRC" 中華民國應譯為「PRC」 [Republic of China should be translated as "PRC"]. Open Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Kucha, Glenn; Llewellyn, Jennifer (12 September 2019). "The Nanjing Decade". Alpha History. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- "Lùntán: Tái zǒngtǒng fǔ wǎngyè jiā zhù"táiwān"" 論壇:台總統府網頁加注"台灣" [Forum: Adding "Taiwan" to the website of Taiwan's Presidential Office] (in Traditional Chinese). BBC 中文網. 2005-08-29. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

台總統府公共事務室陳文宗上周六(7月30日)表示,外界人士易把中華民國(Republic of China),誤認為對岸的中國,造成困擾和不便。公共事務室指出,為了明確區別,決定自周六起於中文繁體、简化字的總統府網站中,在「中華民國」之後,以括弧加注「臺灣」。[Chen Wen-tsong, Public Affairs Office of Taiwan's Presidential Office, stated last Saturday (30 July) that outsiders tend to mistake the Chung-hua Min-kuo (Republic of China) for China on the other side, causing trouble and inconvenience. The Public Affairs Office pointed out that in order to clarify the distinction, it was decided to add "Taiwan" in brackets after "Republic of China" on the website of the Presidential Palace in traditional and simplified Chinese starting from Saturday.]

- Min, Li. "Zhōnghuá mínguó guóhào de lái yóu hé yìyì" 中華民國國號的來由和意義 [The origin and significance of the name of the Republic of China]. Huanghuagang Magazine. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23.

- "Mínguó shíliù nián, guómín zhèngfǔ xuānyán dìng wéi shǒudū, jīn yǐ táiběi shì wèi wǒguó zhōngyāng zhèngfǔ suǒzàidì" 民國十六年,國民政府宣言定為首都,今以臺北市為我國中央政府所在地。 ["In Minguo 16, the National Government declared Nanjing as the capital, and today Taipei City is the seat of our country's central government."]. Re-edited Mandarin Dictionary Revised Edition (in Chinese). Ministry of Education, ROC. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- "Mínguó shíqí (1911-1949) de mùlù yǔ xuézhě shùjùkù" 民國時期(1911-1949)的目錄與學者數據庫 [Catalog and scholar database of the Republican period (1911–1949)]. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- "Mínguó shíqí qíkān quánwén shùjùkù (1911–1949)" 民国时期期刊全文数据库(1911~1949) [Full-text database of periodicals during the Republic (1911–1949)]. Quanguo Baokan Suoyin. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- Ray, Michael; et al., eds. (23 December 2017). "Second Sino-Japanese War". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2023-09-21.

- "Taiwan Timeline – Retreat to Taiwan". BBC News. 2000. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Wang, Yi Chu. "Sun Yat-sen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- Yuekuan, Wen. "Bèi xīfāng yù chéngwéi de "mínguó huángjīn shí nián"" 被西方誉成为的“民国黄金十年” [The age known as the "Golden Decade of the Republic of China" by the West]. Memopol (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2014-02-22.

- Zhanliang, Wu. "Mínguó shíqí de qǐméng yǔ pīpàn qǐméng" 民国时期的启蒙与批判启蒙 [Enlightenment and Critical Enlightenment during the Republic]. National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- "Zhōnghuá mínguó jiǔshísì nián niánjiàn: Dì yī piān zǒng lùn dì èr zhāng tǔdì dì èr jié dàlù dìqū" 中華民國九十四年年鑑:第一篇 總論 第二章 土地 第二節 大陸地區 [Yearbook of the 94th Year of the Republic of China: Part One, General Introduction, Chapter Two, Land, Section Two, Mainland Area]. Government Information Office, Executive Yuan, Republic of China. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Zhōnghuá mínguó línshí dà zǒngtǒng duìwài xuānyán shū" 中华民国临时大总统对外宣言书 [External Declaration of the Provisional President of the Republic of China]. Museum of Dr. Sun Yat-sen. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

抑吾人更有进者,民国与世界各国政府人民之交际,此后必益求辑睦。

Historiography

[edit]- Wright, Tim (2018). Chinese Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199920082.