User:Nhess8/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Nhess8. A user sandbox is a subpage of the user's user page. It serves as a testing spot and page development space for the user and is not an encyclopedia article. |

The earliest known Greek medical school opened in Cnidus in 700 BC. Alcmaeon, author of the first anatomical compilation, worked at this school, and it was here that the practice of observing patients was established. Despite their known respect for Egyptian medicine, attempts to discern any particular influence on Greek practice at this early time have not been dramatically successful because of the lack of sources and the challenge of understanding ancient medical terminology. It is clear, however, that the Greeks imported Egyptian substances into their pharmacopoeia, and the influence became more pronounced after the establishment of a school of Greek medicine in Alexandria.[1]

START EDITS

Pre-Hippocratic Medicine

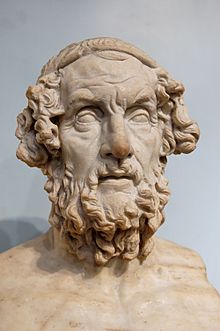

[edit]Knowledge of the field of medicine in Ancient Greece during the Pre-Hippocratic era is relatively limited and most information we have comes from Homer and his epics. Throughout his stories, Homer used a myriad of medical and anatomical descriptions, which are the main source used to discern what was known about medicine before Hippocrates. There were not any solely medical texts written prior to those published by Hippocrates, so the descriptions of injury and disease treatment and human anatomy in Homer's Iliad act as the medical texts of the time. Homer has been attributed with moving his society towards Humanism, which led to the interest in medicine and scientific approaches to it. [2] It was at this point that the people of Ancient Greece started to blame less on the gods and to look for more practical reasons and ways of solving problems.

Medicine in The Iliad

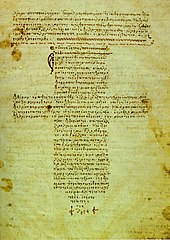

[edit]In Book I of The Iliad when a plague fell on the Achaean soldiers, causing scores of them to die, the soldiers began to think that it was a result of Apollo's anger over Agamemnon's treatment of Chryses. In order for them to be cured they would have to sacrifice and appease the angered god, which when done successfully lifted the plague. Based on this, historians believe that Ancient Greeks saw disease as a work of angered gods, and the only way to be cured was through prayer and sacrifice to that god. [3]. Another way Ancient Greeks sought relief from their ailments was through help from the healing god Asclepius. Although disease was seen as a work of the gods, cases of injury and trauma were dealt with more practically, based on descriptions in "The Iliad". The Achaeans had dedicated healers, specifically Machaon, who was often described dealing with the injuries associated with war. The treatments used were very rudimentary, and consisted mainly of herbs, bandages and wine. The herbs used were generally meant to be analgesics or used for coagulation to prevent bleeding out on the battlefield. [3] Along with practical treatment, it was common for the healers to offer a prayer along with treatment because there was still a belief that gods could and would heal at their discretion. During Pre-Hippocratic times, human dissection was strictly forbidden which made learning about the internal human anatomy extremely difficult. Still, the Iliad discussed human anatomy with reasonable accuracy, suggesting there must have been some anatomical knowledge during the Pre-Hippocratic era. There were references to approximately 147 different body parts throughout the Iliad, including specific terms such as thorax, bronchi, lungs, and diaphragm. [3] According to the Iliad, the Ancient Greeks also attempted to perform rudimentary surgeries, although whether they were done only on the battlefield or in day to day life is unknown. There are multiple times throughout the Iliad in which someone is described using a knife to surgically remove an embedded arrow and then treating the wound, showing understanding of basic surgical practices.

Asclepieia

[edit]

Asclepius was espoused as the first physician, and myth placed him as the son of Apollo. Temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Greek: Ἀσκληπιεῖα; sing. Ἀσκληπιεῖον Asclepieion), functioned as centers of medical advice, prognosis, and healing.[4] At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as "enkoimesis" (Greek: ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery.[5] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[4] The Temple of Asclepius in Pergamum had a spring that flowed down into an underground room in the Temple. People would come to drink the waters and to bathe in them because they were believed to have medicinal properties. Mud baths and hot teas such as chamomile were used to calm them or peppermint tea to sooth their headaches. The patients were encouraged to sleep in the facilities too. Their dreams were interpreted by the doctors and their symptoms were then reviewed. Dogs would occasionally be brought in to lick open wounds for assistance in their healing. In the Asclepieion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BC preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there. Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium.[5]

The Rod of Asclepius is a universal symbol for medicine to this very day. However, it is frequently confused with Caduceus, which was a staff wielded by the god Hermes. The Rod of Asclepius embodies one snake with no wings whereas Caduceus is represented by two snakes and a pair of wings depicting the swiftness of Hermes.

Further reading

[edit]- Annas, Julia Classical Greek Philosophy. In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (ed.) The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press: New York, 1986. ISBN 0-19-872112-9

- Barnes, Jonathan Hellenistic Philosophy and Science. In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (ed.) The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press: New York, 1986. ISBN 0-19-872112-9

- Cohn-Haft, Louis The Public Physicians of Ancient Greece, Northampton, Massachusetts, 1956

- Guido, Majno "The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World", Harvard University Press, 1975

- Guthrie, W. K. C. A History of Greek Philosophy. Volume I: The earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans. Cambridge University Press: New York, 1962. ISBN 0-521-29420-7

- Jones, W. H. S. Philosophy and Medicine in Ancient Greece, Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1946

- Lennox, James (2006-02-15). "Aristotle's Biology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved October 28, 2006.

- Longrigg, James. “Greek Medicine From the Heroic to the Hellenistic Age.” New York, NY, 1998. ISBN 0-415-92087-6.

- Longrigg, James Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcmæon to the Alexandrians, Routledge, 1993.

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. Harvard University Press, 1936. Reprinted by Harper & Row, ISBN 0-674-36150-4, 2005 paperback: ISBN 0-674-36153-9.

- Mason, Stephen F. A History of the Sciences. Collier Books: New York, 1956.

- Mayr, Ernst. The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1982. ISBN 0-674-36445-7

- Nutton, Vivian "The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World", Routledge, 2004

- von Staden H. (ed. trans.). Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-521-23646-0, ISBN 978-0-521-23646-1]

END EDITS

Hippocrates and Hippocratic medicine

[edit]A towering figure in the history of medicine was the physician Hippocrates of Kos (ca. 460 BC – ca. 370 BC), considered the "Father of Modern Medicine."[6][7] The Hippocratic Corpus is a collection of about seventy early medical works from ancient Greece that are associated with Hippocrates and his students. Hippocrates famously wrote the Hippocratic Oath which is relevant and in use by physicians to this day.

The existence of the Hippocratic Oath implies that this "Hippocratic" medicine was practiced by a group of professional physicians bound (at least among themselves) by a strict ethical code. Aspiring students normally paid a fee for training (a provision is made for exceptions) and entered into a virtual family relationship with his teacher. This training included some oral instruction and probably hands-on experience as the teacher's assistant, since the Oath assumes that the student will be interacting with patients. The Oath also places limits on what the physician may or may not do ("To please no one will I prescribe a deadly drug") and intriguingly hints at the existence of another class of professional specialists, perhaps akin to surgeons ("I will leave this operation to be performed by practitioners, specialists in this art").[8]

- ^ Heinrich Von Staden, Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 1-26.

- ^ Grube, G.M.A. (1954). "Greek Medicine and the Greek Genius". Pheonix. 8 (4): 123.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ a b c d Sahlas, Demetrios (2001). "Functional Neuroanatomy in the Pre-Hippocratic Era: Observations from the Iliad of Homer". Neurosurgery. 48 (6): 1352.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Risse, G. B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56 [1]

- ^ a b Askitopoulou, H., Konsolaki, E., Ramoutsaki, I., Anastassaki, E. Surgical cures by sleep induction as the Asclepieion of Epidaurus. The mistory of anesthesia: proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium, by José Carlos Diz, Avelino Franco, Douglas R. Bacon, J. Rupreht, Julián Alvarez. Elsevier Science B.V., International Congress Series 1242(2002), p.11-17. [2]

- ^ Hippocrates: The "Greek Miracle" in Medicine

- ^ The Father of Modern Medicine: Hippocrates

- ^ Owsei Temkin, "What Does the Hippocratic Oath Say?", in "On Second Thought" and Other Essays in the History of Medicine (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), pp. 21-28.