User:Martin Hogbin/Monty Hall problem (draft 2)

The Monty Hall problem is a probability puzzle loosely based on the American television game show Let's Make a Deal. The name comes from the show's original host, Monty Hall. The problem is also called the Monty Hall paradox, as it is a veridical paradox in that the result appears absurd but is demonstrably true.

The problem was originally posed in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975. A well-known statement of the problem was published in Marilyn vos Savant's "Ask Marilyn" column in Parade magazine in 1990:

Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice? (Whitaker 1990)

Although not explicitly stated in this version, the solution is usually based on the additional assumptions that the car is initially equally likely to be behind each door and that the host must open a door showing a goat, must randomly choose which door to open if both hide goats, and must make the offer to switch. As the player cannot be certain which of the two remaining unopened doors is the winning door, most people assume that each of these doors has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter. In fact, under the standard assumptions the player should switch—doing so doubles the probability of winning the car, from 1/3 to 2/3. Other interpretations of the problem have been discussed in mathematical literature where the probability of winning by switching can be anything from 0 to 1.

The Monty Hall problem, in its usual interpretation, is mathematically equivalent to the earlier Three Prisoners problem, and both bear some similarity to the much older Bertrand's box paradox. These and other problems involving unequal distributions of probability are notoriously difficult for people to solve correctly; when the the Monty Hall problem appeared in Parade, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with PhDs, wrote to the magazine claiming the published solution was wrong. Numerous psychological studies examine how these kinds of problems are perceived. Even when given a completely unambiguous statement of the Monty Hall problem, explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still meet the correct answer with disbelief.

Problem

[edit]Steve Selvin described a problem loosely based on the game show Let's Make a Deal in a letter to the American Statistician in 1975 (Selvin 1975a). In a subsequent letter he dubbed it the "Monty Hall problem" (Selvin 1975b). Selvin's "Monty Hall problem" was restated in its well-known form in a letter to Marilyn vos Savant's "Ask Marilyn" column in Parade:

Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats [booby prizes]. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which he knows has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice? (Whitaker 1990)

Certain aspects of the host's behavior are not specified in this wording of the problem. For example it is not clear if the host considers the position of the prize in deciding whether to open a particular door or is required to open a door under all circumstances (Mueser and Granberg 1999). The standard analysis is based on the additional assumptions that the car is initially equally likely to be behind each door and that the host must open a door showing a goat, must randomly choose which door to open if both hide goats, and must make the offer to switch (Barbeau 2000:87). According to Krauss and Wang (2003:10), even if these assumptions are not explicitly stated, people generally assume them to be the case. A fully unambiguous, mathematically explicit version of the standard problem is:

Suppose you’re on a game show and you’re given the choice of three doors. Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. The car and the goats were placed randomly behind the doors before the show. The rules of the game show are as follows: After you have chosen a door, the door remains closed for the time being. The game show host, Monty Hall, who knows what is behind the doors, now has to open one of the two remaining doors, and the door he opens must have a goat behind it. If both remaining doors have goats behind them, he chooses one randomly. After Monty Hall opens a door with a goat, he will ask you to decide whether you want to stay with your first choice or to switch to the last remaining door. Imagine that you chose Door 1 and the host opens Door 3, which has a goat. He then asks you “Do you want to switch to Door Number 2?” Is it to your advantage to change your choice? (Krauss and Wang 2003:10)

Popular solution

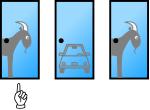

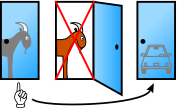

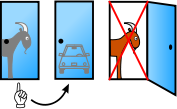

[edit]The solution presented by vos Savant in Parade (vos Savant 1990b) shows the three possible arrangements of one car and two goats behind three doors and the result of switching or staying after initially picking Door 1 in each case:

| Door 1 | Door 2 | Door 3 | result if switching | result if staying |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car | Goat | Goat | Goat | Car |

| Goat | Car | Goat | Car | Goat |

| Goat | Goat | Car | Car | Goat |

A player who stays with the initial choice wins in only one out of three of these equally likely possibilities, while a player who switches wins in two out of three. The probability of winning by staying with the initial choice is therefore 1/3, while the probability of winning by switching is 2/3.

An even simpler solution is to reason that switching loses if and only if the player initially picks the car, which happens with probability 1/3, so switching must win with probability 2/3 (Carlton 2005).

Another way to understand the solution is to consider the two original unchosen doors together. Instead of one door being opened and shown to be a losing door, an equivalent action is to combine the two unchosen doors into one since the player cannot choose the opened door (Adams 1990; Devlin 2003; Williams 2004; Stibel et al., 2008).

As Cecil Adams puts it (Adams 1990), "Monty is saying in effect: you can keep your one door or you can have the other two doors." The player therefore has the choice of either sticking with the original choice of door, or choosing the sum of the contents of the two other doors, as the 2/3 chance of hiding the car hasn't been changed by the opening of one of these doors.

As Keith Devlin says (Devlin 2003), "By opening his door, Monty is saying to the contestant 'There are two doors you did not choose, and the probability that the prize is behind one of them is 2/3. I'll help you by using my knowledge of where the prize is to open one of those two doors to show you that it does not hide the prize. You can now take advantage of this additional information. Your choice of door A has a chance of 1 in 3 of being the winner. I have not changed that. But by eliminating door C, I have shown you that the probability that door B hides the prize is 2 in 3.'"

Aids to understanding

[edit]Why the probability is not 1/2

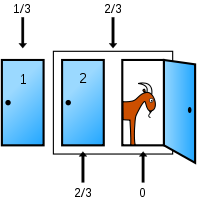

[edit]The contestant has a 1 in 3 chance of selecting the car door in the first round. Then, from the set of two unselected doors, the host non-randomly removes a door that he knows is a goat door. If the contestant originally chose the car door (1/3 of the time) then the remaining door will contain a goat. If the contestant chose a goat door (the other 2/3 of the time) then the remaining door will contain the car.

The critical fact is that the host does not randomly choose a door. Instead, he always chooses a door that he knows contains a goat after the contestant has made their choice. This means that the host's choice does not affect the original probability that the car is behind the contestant's door. When the contestant is asked if the contestant wants to switch, there is still a 1 in 3 chance that the original choice contains a car and a 2 in 3 chance that the original choice contains a goat. But now, the host has removed one of the other doors and the door he removed cannot have the car, so the 2 in 3 chance of the contestant's door containing a goat is the same as a 2 in 3 chance of the remaining door having the car.

This is different from a scenario where the host is choosing his door at random and there is a possibility he will reveal the car. In this instance the revelation of a goat would mean that the chance of the contestant's original choice being the car would go up to 1 in 2. This difference can be demonstrated by contrasting the original problem with a variation that appeared in vos Savant's column in November 2006. In this version, the host forgets which door hides the car. He opens one of the doors at random and is relieved when a goat is revealed. Asked whether the contestant should switch, vos Savant correctly replied, "If the host is clueless, it makes no difference whether you stay or switch. If he knows, switch" (vos Savant, 2006).

Another way of looking at the situation is to consider that if the contestant chooses to switch then they are effectively getting to see what is behind 2 of the 3 doors, and will win if either one of them has the car. In this situation one of the unchosen doors will have the car 2/3 of the time and the other will have a goat 100% of the time. The fact that the host shows one of the doors has a goat before the contestant makes the switch is irrelevant, because one of the doors will always have a goat and the host has chosen it deliberately. The contestant still gets to look behind 2 doors and win if either has the car, it is just confirmed that one of doors will have a goat first.

Increasing the number of doors

[edit]It may be easier to appreciate the solution by considering the same problem with 1,000,000 doors instead of just three (vos Savant 1990). In this case there are 999,999 doors with goats behind them and one door with a prize. The player picks a door. The game host then opens 999,998 of the other doors revealing 999,998 goats—imagine the host starting with the first door and going down a line of 1,000,000 doors, opening each one, skipping over only the player's door and one other door. The host then offers the player the chance to switch to the only other unopened door. On average, in 999,999 out of 1,000,000 times the other door will contain the prize, as 999,999 out of 1,000,000 times the player first picked a door with a goat. A rational player should switch. Intuitively speaking, the player should ask how likely is it, that given a million doors, he or she managed to pick the right one. The example can be used to show how the likelihood of success by switching is equal to (1 minus the likelihood of picking correctly the first time) for any given number of doors. It is important to remember, however, that this is based on the assumption that the host knows where the prize is and must not open a door that contains that prize, randomly selecting which other door to leave closed if the contestant manages to select the prize door initially.

This example can also be used to illustrate the opposite situation in which the host does not know where the prize is and opens doors randomly. There is a 999,999/1,000,000 probability that the contestant selects wrong initially, and the prize is behind one of the other doors. If the host goes about randomly opening doors not knowing where the prize is, the probability is likely that the host will reveal the prize before two doors are left (the contestant's choice and one other) to switch between. This is analogous to the game play on another game show, Deal or No Deal; In that game, the contestant chooses a numbered briefcase and then randomly opens the other cases one at a time.

Stibel et al. (2008) propose working memory demand is taxed during the Monty Hall problem and that this forces people to "collapse" their choices into two equally probable options. They report that when increasing the number of options to over 7 choices (7 doors) people tend to switch more often; however most still incorrectly judge the probability of success at 50/50.

Simulation

[edit]

A simple way to demonstrate that a switching strategy really does win two out of three times on the average is to simulate the game with playing cards (Gardner 1959b; vos Savant 1996:8). Three cards from an ordinary deck are used to represent the three doors; one 'special' card such as the Ace of Spades should represent the door with the car, and ordinary cards, such as the two red twos, represent the goat doors.

The simulation, using the following procedure, can be repeated several times to simulate multiple rounds of the game. One card is dealt face-down at random to the 'player', to represent the door the player picks initially. Then, looking at the remaining two cards, at least one of which must be a red two, the 'host' discards a red two. If the card remaining in the host's hand is the Ace of Spades, this is recorded as a round where the player would have won by switching; if the host is holding a red two, the round is recorded as one where staying would have won.

By the law of large numbers, this experiment is likely to approximate the probability of winning, and running the experiment over enough rounds should not only verify that the player does win by switching two times out of three, but show why. After one card has been dealt to the player, it is already determined whether switching will win the round for the player; and two times out of three the Ace of Spades is in the host's hand.

If this is not convincing, the simulation can be done with the entire deck, dealing one card to the player and keeping the other 51 (Gardner 1959b; Adams 1990). In this variant the Ace of Spades goes to the host 51 times out of 52, and stays with the host no matter how many non-Ace cards are discarded.

Another simulation, suggested by vos Savant, employs the "host" hiding a penny, representing the car, under one of three cups, representing the doors; or hiding a pea under one of three shells.

Probabilistic solution

[edit]Morgan et al. (1991) state that many popular solutions are incomplete, because they do not explicitly address their interpretation of Whitaker's original question (Seymann), which is the specific case of a player who has picked Door 1 and has then seen the host open Door 3. These solutions correctly show that the probability of winning for all players who switch is 2/3, but without certain assumptions this does not necessarily mean the probability of winning by switching is 2/3 given which door the player has chosen and which door the host opens. This probability is a conditional probability (Morgan et al. 1991; Gillman 1992; Grinstead and Snell 2006:137; Gill 2009b). The difference is whether the analysis is of the average probability over all possible combinations of initial player choice and door the host opens, or of only one specific case—for example the case where the player picks Door 1 and the host opens Door 3. Another way to express the difference is whether the player must decide to switch before the host opens a door or is allowed to decide after seeing which door the host opens (Gillman 1992). Although these two probabilities are both 2/3 for the unambiguous problem statement presented above, the conditional probability may differ from the overall probability and either or both may not be able to be determined depending on the exact formulation of the problem (Gill 2009b).

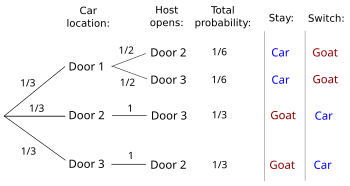

The conditional probability of winning by switching given which door the host opens can be determined referring to the expanded figure below, or to an equivalent decision tree as shown to the right (Chun 1991; Grinstead and Snell 2006:137-138), or formally derived as in the mathematical formulation section below. For example, if the host opens Door 3 and the player switches, the player wins with overall probability 1/3 if the car is behind Door 2 and loses with overall probability 1/6 if the car is behind Door 1—the possibilities involving the host opening Door 2 do not apply. To convert these to conditional probabilities they are divided by their sum, so the conditional probability of winning by switching given the player picks Door 1 and the host opens Door 3 is (1/3)/(1/3 + 1/6), which is 2/3. This analysis depends on the constraint in the explicit problem statement that the host chooses randomly which door to open after the player has initially selected the car.

Mathematical formulation

[edit]The above solution may be formally proven using Bayes' theorem, similar to Gill, 2002, Henze, 1997 and many others. Different authors use different formal notations, but the one below may be regarded as typical. Consider the discrete random variables:

- C: the number of the door hiding the Car,

- S: the number of the door Selected by the player, and

- H: the number of the door opened by the Host,

each with values in {1,2,3}.

As the host's placement of the car is random, all values of C are equally likely. The initial (unconditional) probability of C is then

- , for every value c of C.

Further, as the initial choice of the player is independent of the placement of the car, variables C and S are independent. Hence the conditional probability of C given S is

- , for every value c of C and s of S.

The host's behavior is reflected by the values of the conditional probability of H given C and S:

-

if h = s, (the host cannot open the door picked by the player) if h = c, (the host cannot open a door with a car behind it) if s = c, (the two doors with no car are equally likely to be opened) if h c and s c, (there is only one door available to open)

The player can then use Bayes' rule to compute the probability of finding the car behind any door, after the initial selection and the host's opening of one. This is the conditional probability of C given H and S:

- ,

where the denominator is computed as the marginal probability

- .

Thus, if the player initially selects Door 1, and the host opens Door 3, the probability of winning by switching is

Sources of confusion

[edit]When first presented with the Monty Hall problem an overwhelming majority of people assume that each door has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter (Mueser and Granberg, 1999). Out of 228 subjects in one study, only 13% chose to switch (Granberg and Brown, 1995:713). In her book The Power of Logical Thinking, vos Savant (1996:15) quotes cognitive psychologist Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini as saying "... no other statistical puzzle comes so close to fooling all the people all the time" and "that even Nobel physicists systematically give the wrong answer, and that they insist on it, and they are ready to berate in print those who propose the right answer."

Most statements of the problem, notably the one in Parade Magazine, do not match the rules of the actual game show (Krauss and Wang, 2003:9), and do not fully specify the host's behavior or that the car's location is randomly selected (Granberg and Brown, 1995:712). Krauss and Wang (2003:10) conjecture that people make the standard assumptions even if they are not explicitly stated. Although these issues are mathematically significant, even when controlling for these factors nearly all people still think each of the two unopened doors has an equal probability and conclude switching does not matter (Mueser and Granberg, 1999). This "equal probability" assumption is a deeply rooted intuition (Falk 1992:202). People strongly tend to think probability is evenly distributed across as many unknowns as are present, whether it is or not (Fox and Levav, 2004:637).

A competing deeply rooted intuition at work in the Monty Hall problem is the belief that exposing information that is already known does not affect probabilities (Falk 1992:207). This intuition is the basis of solutions to the problem that assert the host's action of opening a door does not change the player's initial 1/3 chance of selecting the car. For the fully explicit problem this intuition leads to the correct numerical answer, 2/3 chance of winning the car by switching, but leads to the same solution for slightly modified problems where this answer is not correct (Falk 1992:207).

According to Morgan et al. (1991) "The distinction between the conditional and unconditional situations here seems to confound many." That is, they, and some others, interpret the usual wording of the problem statement as asking about the conditional probability of winning given which door is opened by the host, as opposed to the overall or unconditional probability. These are mathematically different questions and can have different answers depending on how the host chooses which door to open when the player's initial choice is the car (Morgan et al., 1991; Gillman 1992). For example, if the host opens Door 3 whenever possible then the probability of winning by switching for players initially choosing Door 1 is 2/3 overall, but only 1/2 if the host opens Door 3. In its usual form the problem statement does not specify this detail of the host's behavior, nor make clear whether a conditional or an unconditional answer is required, making the answer that switching wins the car with probability 2/3 equally vague. Many commonly presented solutions address the unconditional probability, ignoring which door was chosen by the player and which door opened by the host; Morgan et al. call these "false solutions" (1991). Others, such as Behrends (2008), conclude that "One must consider the matter with care to see that both analyses are correct."

Variants - slightly modified problems

[edit]Other host behaviors

[edit]The version of the Monty Hall problem published in Parade in 1990 did not specifically state that the host would always open another door, or always offer a choice to switch, or even never open the door revealing the car. However, vos Savant made it clear in her second followup column that the intended host's behavior could only be what led to the 2/3 probability she gave as her original answer. "Anything else is a different question" (vos Savant, 1991). "Virtually all of my critics understood the intended scenario. I personally read nearly three thousand letters (out of the many additional thousands that arrived) and found nearly every one insisting simply that because two options remained (or an equivalent error), the chances were even. Very few raised questions about ambiguity, and the letters actually published in the column were not among those few." (vos Savant, 1996) The answer follows if the car is placed randomly behind any door, the host must open a door revealing a goat regardless of the player's initial choice and, if two doors are available, chooses which one to open randomly (Mueser and Granberg, 1999). The table below shows a variety of OTHER possible host behaviors and the impact on the success of switching.

Determining the player's best strategy within a given set of other rules the host must follow is the type of problem studied in game theory. For example, if the host is not required to make the offer to switch the player may suspect the host is malicious and makes the offers more often if the player has initially selected the car. In general, the answer to this sort of question depends on the specific assumptions made about the host's behaviour, and might range from "ignore the host completely" to 'toss a coin and switch if it comes up heads', see the last row of the table below.

Morgan et al. (1991) and Gillman (1992) both show a more general solution where the car is randomly placed but the host is not constrained to pick randomly if the player has initially selected the car, which is how they both interpret the well known statement of the problem in Parade despite the author's disclaimers. Both changed the wording of the Parade version to emphasize that point when they restated the problem. They consider a scenario where the host chooses between revealing two goats with a preference expressed as a probability q, having a value between 0 and 1. If the host picks randomly q would be 1/2 and switching wins with probability 2/3 regardless of which door the host opens. If the player picks Door 1 and the host's preference for Door 3 is q, then in the case where the host opens Door 3 switching wins with probability 1/3 if the car is behind Door 2 and loses with probability (1/3)q if the car is behind Door 1. The conditional probability of winning by switching given the host opens Door 3 is therefore (1/3)/(1/3 + (1/3)q) which simplifies to 1/(1+q). Since q can vary between 0 and 1 this conditional probability can vary between 1/2 and 1. This means even without constraining the host to pick randomly if the player initially selects the car, the player is never worse off switching. However, it is important to note that neither source suggests the player knows what the value of q is, so the player cannot attribute a probability other than the 2/3 that vos Savant assumed was implicit.

| Possible host behaviors in unspecified problem | |

|---|---|

| Host behavior | Result |

| "Monty from Hell": The host offers the option to switch only when the player's initial choice is the winning door (Tierney 1991). | Switching always yields a goat. |

| "Angelic Monty": The host offers the option to switch only when the player has chosen incorrectly (Granberg 1996:185). | Switching always wins the car. |

| "Monty Fall" or "Ignorant Monty": The host does not know what lies behind the doors, and opens one at random that happens not to reveal the car (Granberg and Brown, 1995:712) (Rosenthal, 2008). | Switching wins the car half of the time. |

| The host knows what lies behind the doors, and (before the player's choice) chooses at random which goat to reveal. He offers the option to switch only when the player's choice happens to differ from his. | Switching wins the car half of the time. |

| The host always reveals a goat and always offers a switch. If he has a choice, he chooses the leftmost goat with probability p (which may depend on the player's initial choice) and the rightmost door with probability q=1−p. (Morgan et al. 1991) (Rosenthal, 2008). | If the host opens the rightmost door, switching wins with probability 1/(1+q). |

| The host acts as noted in the specific version of the problem. | Switching wins the car two-thirds of the time. (Special case of the above with p=q=½) |

| The host is rewarded whenever the contestant incorrectly switches or incorrectly stays. [citation needed] | Switching wins 1/2 the time at the Nash equilibrium. |

| Four-stage two-player game-theoretic (Gill, 2009a, Gill, 2009b, Gill, 2010). The player is playing against the show organisers (TV station) which includes the host. First stage: organizers choose a door (choice kept secret from player). Second stage: player makes a preliminary choice of door. Third stage: host opens a door. Fourth stage: player makes a final choice. The player wants to win the car, the TV station wants to keep it. This is a zero-sum two-person game. By von Neumann's theorem from game theory, if we allow both parties fully randomized strategies there exists a minimax solution or Nash equilibrium. | Minimax solution (Nash equilibrium): car is first hidden uniformly at random and host later chooses uniform random door to open without revealing the car and different from player's door; player first chooses uniform random door and later always switches to other closed door. With his strategy, the player has a win-chance of at least 2/3, however the TV station plays; with the TV station's strategy, the TV station will lose with probability at most 2/3, however the player plays. The fact that these two strategies match (at least 2/3, at most 2/3) proves that they form the minimax solution. |

| As previous, but now host has option not to open a door at all. | Minimax solution (Nash equilibrium): car is first hidden uniformly at random and host later never opens a door; player first chooses a door uniformly at random and later never switches. Player's strategy guarantees a win-chance of at least 1/3. TV station's strategy guarantees a lose-chance of at most 1/3. |

N doors

[edit]D. L. Ferguson (1975 in a letter to Selvin cited in Selvin 1975b) suggests an N door generalization of the original problem in which the host opens p losing doors and then offers the player the opportunity to switch; in this variant switching wins with probability (N−1)/[N(N−p−1)]. If the host opens even a single door the player is better off switching, but the advantage approaches zero as N grows large (Granberg 1996:188). At the other extreme, if the host opens all but one losing door the probability of winning by switching approaches 1.

Bapeswara Rao and Rao (1992) suggest a different N door version where the host opens a losing door different from the player's current pick and gives the player an opportunity to switch after each door is opened until only two doors remain. With four doors the optimal strategy is to pick once and switch only when two doors remain. With N doors this strategy wins with probability (N−1)/N and is asserted to be optimal.

Quantum version

[edit]A quantum version of the paradox illustrates some points about the relation between classical or non-quantum information and quantum information, as encoded in the states of quantum mechanical systems. The formulation is loosely based on Quantum game theory. The three doors are replaced by a quantum system allowing three alternatives; opening a door and looking behind it is translated as making a particular measurement. The rules can be stated in this language, and once again the choice for the player is to stick with the initial choice, or change to another "orthogonal" option. The latter strategy turns out to double the chances, just as in the classical case. However, if the show host has not randomized the position of the prize in a fully quantum mechanical way, the player can do even better, and can sometimes even win the prize with certainty (Flitney and Abbott 2002, D'Ariano et al. 2002).

History of the problem

[edit]The earliest of several probability puzzles related to the Monty Hall problem is Bertrand's box paradox, posed by Joseph Bertrand in 1889 in his Calcul des probabilités (Barbeau 1993). In this puzzle there are three boxes: a box containing two gold coins, a box with two silver coins, and a box with one of each. After choosing a box at random and withdrawing one coin at random that happens to be a gold coin, the question is what is the probability that the other coin is gold. As in the Monty Hall problem the intuitive answer is 1/2, but the probability is actually 2/3.

The Three Prisoners problem, published in Martin Gardner's Mathematical Games column in Scientific American in 1959 (1959a, 1959b), is isomorphic to the Monty Hall problem. This problem involves three condemned prisoners, a random one of whom has been secretly chosen to be pardoned. One of the prisoners begs the warden to tell him the name of one of the others who will be executed, arguing that this reveals no information about his own fate but increases his chances of being pardoned from 1/3 to 1/2. The warden obliges, (secretly) flipping a coin to decide which name to provide if the prisoner who is asking is the one being pardoned. The question is whether knowing the warden's answer changes the prisoner's chances of being pardoned. This problem is equivalent to the Monty Hall problem; the prisoner asking the question still has a 1/3 chance of being pardoned but his unnamed cohort has a 2/3 chance.

Steve Selvin posed the Monty Hall problem in a pair of letters to the American Statistician in 1975 (1975a, 1975b). The first letter presented the problem in a version close to its presentation in Parade 15 years later. The second appears to be the first use of the term "Monty Hall problem". The problem is actually an extrapolation from the game show. Monty Hall did open a wrong door to build excitement, but offered a known lesser prize—such as $100 cash—rather than a choice to switch doors. As Monty Hall wrote to Selvin:

And if you ever get on my show, the rules hold fast for you—no trading boxes after the selection. (Hall 1975)

A version of the problem very similar to the one that appeared three years later in Parade was published in 1987 in the Puzzles section of The Journal of Economic Perspectives (Nalebuff 1987).

Phillip Martin's article in a 1989 issue of Bridge Today magazine titled "The Monty Hall Trap" (Martin 1989) presented Selvin's problem as an example of what Martin calls the probability trap of treating non-random information as if it were random, and relates this to concepts in the game of bridge.

A restated version of Selvin's problem appeared in Marilyn vos Savant's Ask Marilyn question-and-answer column of Parade in September 1990 (vos Savant 1990). Though vos Savant gave the correct answer that switching would win two-thirds of the time, she estimates the magazine received 10,000 letters including close to 1,000 signed by PhDs, many on letterheads of mathematics and science departments, declaring that her solution was wrong (Tierney 1991). Due to the overwhelming response, Parade published an unprecedented four columns on the problem (vos Savant 1996:xv). As a result of the publicity the problem earned the alternative name Marilyn and the Goats.

In November 1990, an equally contentious discussion of vos Savant's article took place in Cecil Adams's column The Straight Dope (Adams 1990). Adams initially answered, incorrectly, that the chances for the two remaining doors must each be one in two. After a reader wrote in to correct the mathematics of Adams' analysis, Adams agreed that mathematically, he had been wrong, but said that the Parade version left critical constraints unstated, and without those constraints, the chances of winning by switching were not necessarily 2/3. Numerous readers, however, wrote in to claim that Adams had been "right the first time" and that the correct chances were one in two.

The Parade column and its response received considerable attention in the press, including a front page story in the New York Times (Tierney 1991) in which Monty Hall himself was interviewed. He appeared to understand the problem, giving the reporter a demonstration with car keys and explaining how actual game play on Let's Make a Deal differed from the rules of the puzzle.

Over 40 papers have been published about this problem in academic journals and the popular press (Mueser and Granberg 1999). Barbeau 2000 contains a survey of the academic literature pertaining to the Monty Hall problem and other closely related problems.

The problem continues to resurface outside of academia. The syndicated NPR program Car Talk featured it as one of their weekly "Puzzlers," and the answer they featured was quite clearly explained as the correct one (Magliozzi and Magliozzi, 1998). An account of the Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdős's first encounter of the problem can be found in The Man Who Loved Only Numbers—like many others, he initially got it wrong. The problem is discussed, from the perspective of a boy with Asperger syndrome, in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, a 2003 novel by Mark Haddon. The problem is also addressed in a lecture by the character Charlie Eppes in an episode of the CBS drama NUMB3RS (Episode 1.13) and in Derren Brown's 2006 book Tricks Of The Mind. Penn Jillette explained the Monty Hall Problem on the "Luck" episode of Bob Dylan's Theme Time Radio Hour radio series. The Monty Hall problem appears in the film 21 (Bloch 2008). Economist M. Keith Chen identified a potential flaw in hundreds of experiments related to cognitive dissonance that use an analysis with issues similar to those involved in the Monty Hall problem (Tierney 2008).

See also

[edit]- Bayes' theorem: The Monty Hall problem

- Principle of restricted choice (bridge)

- Make Your Mark (Pricing Game)

Similar problems

[edit]- Bertrand's box paradox (also known as the three-cards problem)

- Boy or Girl paradox

- Three Prisoners problem

- Two envelopes problem

References

[edit]- Adams, Cecil (1990)."On 'Let's Make a Deal,' you pick Door #1. Monty opens Door #2—no prize. Do you stay with Door #1 or switch to #3?", The Straight Dope, (November 2, 1990). Retrieved July 25, 2005.

- Bapeswara Rao, V. V. and Rao, M. Bhaskara (1992). "A three-door game show and some of its variants". The Mathematical Scientist 17(2): 89–94.

- Barbeau, Edward (1993). "Fallacies, Flaws, and Flimflam: The problem of the Car and Goats". The College Mathematics Journal 24(2): 149-154.

- Barbeau, Edward (2000). Mathematical Fallacies, Flaws and Flimflam. The Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-529-1.

- Behrends, Ehrhard (2008). Five-Minute Mathematics. AMS Bookstore. p. 57. ISBN 9780821843482.

- Bloch, Andy (2008). "21 - The Movie (my review)". Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Carlton, Matthew (2005). "Pedigrees, Prizes, and Prisoners: The Misuse of Conditional Probability". Journal of Statistics Education [online]. 13 (2). Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- Chun, Young H. (1991). "Game Show Problem," OR/MS Today 18(3): 9.

- D'Ariano, G.M et al. (2002). "The Quantum Monty Hall Problem" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory, (February 21, 2002). Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- Devlin, Keith (July – August 2003). "Devlin's Angle: Monty Hall". The Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "The Monty Hall puzzle". The Economist. Vol. 350. The Economist Newspaper. 1999. p. 110.

- Falk, Ruma (1992). "A closer look at the probabilities of the notorious three prisoners," Cognition 43: 197–223.

- Flitney, Adrian P. and Abbott, Derek (2002). "Quantum version of the Monty Hall problem," Physical Review A, 65, Art. No. 062318, 2002.

- Fox, Craig R. and Levav, Jonathan (2004). "Partition-Edit-Count: Naive Extensional Reasoning in Judgment of Conditional Probability," Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 133(4): 626-642.

- Gardner, Martin (1959a). "Mathematical Games" column, Scientific American, October 1959, pp. 180–182. Reprinted in The Second Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles and Diversions.

- Gardner, Martin (1959b). "Mathematical Games" column, Scientific American, November 1959, p. 188.

- Gill, Jeff (2002). Bayesian Methods, pp. 8–10. CRC Press. ISBN 1-58488-288-3, (restricted online copy, p. 8, at Google Books)

- Gill, Richard (2009a) Probabilistic and Game Theoretic Solutions to the Three Doors Problem, prepublication, http://www.math.leidenuniv.nl/~gill/threedoors.pdf.

- Gill, Richard (2009b) Supplement to Gill (2009a), prepublication, http://www.math.leidenuniv.nl/~gill/quizmaster2.pdf

- Gill, Richard (2010) Second supplement to Gill (2009a), prepublication, http://www.math.leidenuniv.nl/~gill/montyhall3.pdf

- Gillman, Leonard (1992). "The Car and the Goats," American Mathematical Monthly 99: 3–7.

- Granberg, Donald (1996). "To Switch or Not to Switch". Appendix to vos Savant, Marilyn, The Power of Logical Thinking. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-612-30463-3 Parameter error in {{ISBN}}: checksum, (restricted online copy, p. 169, at Google Books).

- Granberg, Donald and Brown, Thad A. (1995). "The Monty Hall Dilemma," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21(7): 711-729.

- Grinstead, Charles M. and Snell, J. Laurie (2006-07-04). Grinstead and Snell's Introduction to Probability (PDF). Retrieved 2008-04-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Online version of Introduction to Probability, 2nd edition, published by the American Mathematical Society, Copyright (C) 2003 Charles M. Grinstead and J. Laurie Snell. - Hall, Monty (1975). The Monty Hall Problem. LetsMakeADeal.com. Includes May 12, 1975 letter to Steve Selvin. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- Henze, Norbert (1997). Stochastik für Einsteiger: Eine Einführung in die faszinierende Welt des Zufalls, pp. 105, Vieweg Verlag, ISBN 3-8348-0091-0, (restricted online copy, p. 105, at Google Books)

- Herbranson, W. T. and Schroeder, J. (2010). "Are birds smarter than mathematicians? Pigeons (Columba livia) perform optimally on a version of the Monty Hall Dilemma." J. Comp. Psychol. 124(1): 1-13. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20175592 March 1, 2010.

- Krauss, Stefan and Wang, X. T. (2003). "The Psychology of the Monty Hall Problem: Discovering Psychological Mechanisms for Solving a Tenacious Brain Teaser," Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 132(1). Retrieved from http://www.usd.edu/~xtwang/Papers/MontyHallPaper.pdf March 30, 2008.

- Mack, Donald R. (1992). The Unofficial IEEE Brainbuster Gamebook. Wiley-IEEE. p. 76. ISBN 9780780304239.

- Magliozzi, Tom; Magliozzi, Ray (1998). Haircut in Horse Town: & Other Great Car Talk Puzzlers. Diane Pub Co. ISBN 0-7567-6423-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Martin, Phillip (1989). "The Monty Hall Trap", Bridge Today, May–June 1989. Reprinted in Granovetter, Pamela and Matthew, ed. (1993), For Experts Only, Granovetter Books.

- Martin, Robert M. (2002). There are two errors in the the title of this book (2nd ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9781551114934.

- Morgan, J. P., Chaganty, N. R., Dahiya, R. C., & Doviak, M. J. (1991). "Let's make a deal: The player's dilemma," American Statistician 45: 284-287.

- Mueser, Peter R. and Granberg, Donald (May 1999). "The Monty Hall Dilemma Revisited: Understanding the Interaction of Problem Definition and Decision Making", University of Missouri Working Paper 99-06. Retrieved July 5, 2005.

- Nalebuff, Barry (1987). "Puzzles: Choose a Curtain, Duel-ity, Two Point Conversions, and More," Journal of Economic Perspectives 1(2): 157-163 (Autumn, 1987).

- Rosenthal, Jeffrey S. (September 2008). "Monty Hall, Monty Fall, Monty Crawl" (PDF). Math Horizons. 16: 5–7. doi:10.1080/10724117.2008.11974778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Selvin, Steve (1975a). "A problem in probability" (letter to the editor). American Statistician 29(1): 67 (February 1975).

- Selvin, Steve (1975b). "On the Monty Hall problem" (letter to the editor). American Statistician 29(3): 134 (August 1975).

- Seymann R. G. (1991). "Comment on Let's make a deal: The player's dilemma," American Statistician 45: 287-288.

- Stibel, Jeffrey, Dror, Itiel, & Ben-Zeev, Talia (2008). "The Collapsing Choice Theory: Dissociating Choice and Judgment in Decision Making," Theory and Decision. Full paper can be found at http://users.ecs.soton.ac.uk/id/TD%20choice%20and%20judgment.pdf.

- Tierney, John (1991). "Behind Monty Hall's Doors: Puzzle, Debate and Answer?", The New York Times, 1991-07-21. Retrieved on 2008-01-18.

- Tierney, John (2008). "And Behind Door No. 1, a Fatal Flaw", The New York Times, 2008-04-08. Retrieved on 2008-04-08.

- vos Savant, Marilyn (1990). "Ask Marilyn" column, Parade Magazine p. 16 (9 September 1990).

- vos Savant, Marilyn (1990b). "Ask Marilyn" column, Parade Magazine p. 25 (2 December 1990).

- vos Savant, Marilyn (1991). "Ask Marilyn" column, Parade Magazine p. 12 (17 February 1991).

- vos Savant, Marilyn (1996). The Power of Logical Thinking. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-15627-8.

- vos Savant, Marilyn (2006). "Ask Marilyn" column, Parade Magazine p. 6 (26 November 2006).

- Schwager, Jack D. (1994). The New Market Wizards. Harper Collins. p. 397. ISBN 9780887306679.

- Williams, Richard (2004). "Appendix D: The Monty Hall Controversy" (PDF). Course notes for Sociology Graduate Statistics I. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Wheeler, Ward C. (1991). "Congruence Among Data Sets: A Bayesian Approach". In Michael M. Miyamoto and Joel Cracraft (ed.). Phylogenetic analysis of DNA sequences. Oxford University Press US. p. 335. ISBN 9780195066982.

- Whitaker, Craig F. (1990). [Letter]. "Ask Marilyn" column, Parade Magazine p. 16 (9 September 1990).

External links

[edit]- The Game Show Problem–the original question and responses on Marilyn vos Savant's web site

- "Monty Hall Paradox" by Matthew R. McDougal, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project (simulation)

- The Monty Hall Problem at The New York Times (simulation)