User:Lovewhatyoudo/sandbox

Nomenclature

[edit]lead paragraph

[edit][...], is the koiné language among the Mandarin dialect group. As a koiné, it arose in the Qing China capital, Beijing, in early 19th century through contact, mixing and simplification of various Mandarin dialects. During the 20th century, it was designated and promoted to be the lingua franca of other varieties of Chinese that is not within Mandarin (Shanghainese, Hokkien, Cantonese and beyond). Standard Beijing Mandarin is designated as one of the major languages in the United Nations, mainland China, Singapore and Taiwan, though the language is known in different names in different jurisdiction.

Like other Sinitic languages, Standard Mandarin is a tonal language with topic-prominent organization and subject–verb–object word order. It has more initial consonants but fewer vowels, final consonants and tones than southern varieties. Standard Mandarin is an analytic language, though with many compound words.

Definitions of Standard

[edit]Standard Beijing Mandarin[1][2][3] is the most precise name. As linguists point out, "One Northern Mandarin dialect, [Standard] Beijing Mandarin, is officially designated as the phonological basis for the standard language".[4]

As the standard of Chinese has not always been the Mandarin variety, much less the Beijing dialect of it, many alternative names are misleading. In ancient China such as the times of Confucius, he spoke the "received standard" (雅言) of Old Chinese, which is not any form of Mandarin; even in a modern context, "the term Chinese [as in Standard Chinese] masks linguistic diversity and complexity among and within regional language varieties [that may or may not be Mandarin], by associating the term Chinese... the singular label makes invisible, or rather erases, the vast number of languages".[4] The alternative name Standard Northern Mandarin masks the changing standards within Northern Mandarin (the Luoyang standard, Khanbaliq standard and the current Beijing standard), whereas Standard Mandarin further mask the shifting of standards from Southern Mandarin (old Luoyang standard, Hangzhou standard and Nanking Mandarin) to Northern Mandarin.[5] The shortened alternative name Mandarin masks the diversity of vocabulary and phonology in the abovementioned historical standard dialects.[6]

Direct quotes:

- Chinese, or Chinese language, Zhongwen, in its singular form, implies a monolithic entity, whereas in reality, the so-called "Chinese language" consists of numerous fangyan, or groups of regional varieties, some of which can be as different as the Romance languages of Europe.[4]

- a widely shared view among many native Chinese speakers that various fangyan are subvarieties of a single language called Chinese. The fact that speakers of diverse, even mutually intelligible fangyan, share a standard Chinese writing system further strengthens this belief in a shared Chinese language among speakers of regional varieties.[4]

- The term Zhongwen, literally "Chinese language", is used to differentiate Chinese from non-Sinitic languages. ..... Both Zhongwen and Hanyu are often used to refer to Mandarin..... For example, the official dictionary that codifies the pronunciation of the standard languages is titled Xiandai Hanyu Cidian (Modern Han Language Dictionary)..... The official standard alphabetical system is called Hanyu Pin (Han language spelling-pronunciation"[4]

Beijing dialect is one of historic standards of Northern Mandarin[5] Hangzhou dialect [7]

The name "Modern Standard Mandarin" is used to distinguish its historic standard.[8][9]

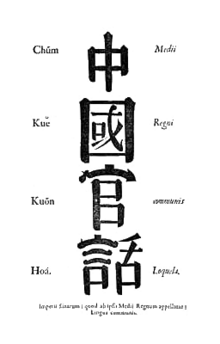

The term "Mandarin" is a translation of Guānhuà (官话; 官話, literally "bureaucrats' speech"),[8] which referred to the Imperial Mandarin.[10] Not only do the phonology and vocabulary of these historical Standard Mandarin dialects distinguish one from another significantly at its time, each one of them has evolved away from itself over time. It has been much of academic interest to search for their modern successor. For example, the Standard Mandarin in Khanbaliq (i.e. Beijing in the Mongol Empire) is often compared to modern Jiao–Liao Mandarin in Shandong peninsula;[11] while the direct descendant of Standard Nanking Mandarin of Ming dynasty is often said to be Yunnan Mandarin in Yunnan[12][13] and Tunbao dialects in Guizhou,[14][13] both belonging to Southwestern Mandarin.

In Chinese

[edit]Guoyu and Putonghua

[edit]Guóyǔ (國語/国语)[8] or "the national language", had previously been used by Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty of China to refer to the Manchurian language. As early as 1655, in Memoir of Qing Dynasty, Volume: Emperor Nurhaci (清太祖实录), it writes "(In 1631) as Manchu ministers do not comprehend the Han language, each ministry shall create a new position to be filled up by Han official who can comprehend the national language."[18] In 1909, the Qing education ministry officially proclaimed Imperial Mandarin to be the new "national language".[19]

Pǔtōnghuà (普通话)[8] or "common tongue", dated back to 1906 by Zhu Wenxiong in Jiangsu New Alphabets to differentiate "the tongue known across provinces" (各省通行之話) from classical Chinese and other varieties of Chinese.[20][21] The widespread usage of Pǔtōnghuà is usually accredited to Qu Qiubai around 1931,[22] which will be discussed in the next paragraph. Conceptually, any dialect of Mandarin or even any variety of Chinese could emerge as the common tongue as long as it is commonly spoken, yet it was politically decided to be reserved for the exclusive usage of Standard Beijing Mandarin in 1955 by PRC.

Usage concern in a multi-ethnic nation

[edit]"The Countrywide Spoken and Written Language" (國家通用語言文字) has been increasingly used by the PRC government since the 2010s, mostly targeting students of ethnic minorities. The term has a strong connotation of being a "legal requirement" as it derives its name from the title of a law passed in 2000. The 2000 law defines Pǔtōnghuà as the one and only one "Countrywide Spoken and Written Language".

The term Pǔtōnghuà (common tongue) deliberately shy from calling itself "the national language". This is to mitigate the impression of forcing ethnic minorities to adapt the language of the dominant ethnic group. Such concern was first raised by Qu Qiubai in 1931, an early Chinese communist revolutionary leader. His concern echoed within the Communist Party, which adopted the name Putonghua in 1955.[23][24] Since 1949, the word Guóyǔ by in large phase out in PRC, only surviving its usage in established compound nouns, e.g. Guóyǔ liúxíng yīnyuè (国语流行音乐, colloquially Mandarin pop), Guóyǔ piān or Guóyǔ diànyǐng (国语片/国语电影, colloquially Mandarin cinema).

In Taiwan, Guóyǔ (the national language) has been the colloquial term for Standard Northern Mandarin. In 2017 and 2018, the Taiwanese government introduce two laws to explicitly recognize indigenous Formosan languages[25][26] and Hakka[27][26] to be "Languages of the nation" (國家語言, notice the plural form) along with Standard Northern Mandarin. Since then, there has been efforts to reclaim the term "the national language" (Guóyǔ) to encompass all "languages of the nation" rather than exclusively referring Standard Northern Mandarin.

Hanyu and Zhongwen

[edit]Among Chinese people, Hànyǔ (漢語/汉语) or "Sinitic languages" refer to all language varieties of the Han people. Zhōngwén (中文)[28] or "Chinese written language", refer to all written languages of Chinese (Sinitic). However, gradually these two terms have been reappropriated to exclusively refers to one particular Sinitic language, the Standard Northern Mandarin, a.k.a. Standard Chinese. Such imprecise usage lead to odd conversation in Taiwan, Malaysia and Singapore as follows:

- (1) A Standard Northern Mandarin speaker approached speakers of other varieties of Chinese and asked, "Do you speak Zhōngwén?" This would be deemed disrespectful.

- (2) A native speaker of certain varieties of Chinese admitted his spoken Zhōngwén is poor.

On the other hand, among foreigners, the term Hànyǔ is most commonly used in textbooks and standardized testing of Standard Chinese for foreigners, e.g. Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi.

Huayu

[edit]Huáyǔ (華語/华语), or "language among the Chinese nation", up until the mid 1960s, refer to all language varieties among the Chinese nation. [29] For example, Cantonese films, Hokkien films (廈語片) and Mandarin films produced in Hong Kong that got imported into Malaysia were collectively known as Huáyǔ cinema up until the mid-1960s.[29] However, gradually it has been reappropriated to exclusively refers to one particular language among the Chinese nation, the Standard Northern Mandarin, a.k.a. Standard Chinese. This term is mostly used in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines.[30]

History of Promoting the standard

[edit]The Chinese have different languages in different provinces, to such an extent that they cannot understand each other.... [They] also have another language which is like a universal and common language; this is the official language of the mandarins and of the court; it is among them like Latin among ourselves.... Two of our fathers [Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci] have been learning this mandarin language...

— Alessandro Valignano, Historia del Principio y Progresso de la Compañia de Jesus en las Indias Orientales (1542–1564)[31]

Chinese has long had considerable dialectal variation, hence prestige dialects have always existed, and linguae francae have always been needed. Confucius, for example, used yǎyán (雅言; 'elegant speech') rather than colloquial regional dialects; text during the Han dynasty also referred to tōngyǔ (通语; 'common language'). Rime books, which were written since the Northern and Southern dynasties, may also have reflected one or more systems of standard pronunciation during those times. However, all of these standard dialects were probably unknown outside the educated elite; even among the elite, pronunciations may have been very different, as the unifying factor of all Chinese dialects, Classical Chinese, was a written standard, not a spoken one.

Late empire

[edit]

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) began to use the term guānhuà (官话/官話), or "official speech", to refer to the speech used at the courts. The term "Mandarin" is borrowed directly from Portuguese. The Portuguese word mandarim, derived from the Sanskrit word mantrin "counselor or minister", was first used to refer to the Chinese bureaucratic officials. The Portuguese then translated guānhuà as "the language of the mandarins" or "the mandarin language".[9]

In the 17th century, the Empire had set up Orthoepy Academies (正音書院; Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn) in an attempt to make pronunciation conform to the standard. But these attempts had little success, since as late as the 19th century the emperor had difficulty understanding some of his own ministers in court, who did not always try to follow any standard pronunciation.

Before the 19th century, the standard was based on the Nanjing dialect, but later the Beijing dialect became increasingly influential, despite the mix of officials and commoners speaking various dialects in the capital, Beijing.[33] By some accounts, as late as the early 20th century, the position of Nanjing Mandarin was considered to be higher than that of Beijing by some and the postal romanization standards set in 1906 included spellings with elements of Nanjing pronunciation.[34] Nevertheless, by 1909, the dying Qing dynasty had established the Beijing dialect as guóyǔ (国语/國語), or the "national language".

As the island of Taiwan had fallen under Japanese rule per the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, the term kokugo (Japanese: 國語, "national language") referred to the Japanese language until the handover to the Republic of China in 1945.

Modern China

[edit]After the Republic of China was established in 1912, there was more success in promoting a common national language. A Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation was convened with delegates from the entire country.[35] A Dictionary of National Pronunciation (国音字典/國音字典) was published in 1919, defining a hybrid pronunciation that did not match any existing speech.[36][37] Meanwhile, despite the lack of a workable standardized pronunciation, colloquial literature in written vernacular Chinese continued to develop apace.[38]

Gradually, the members of the National Language Commission came to settle upon the Beijing dialect, which became the major source of standard national pronunciation due to its prestigious status. In 1932, the commission published the Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use (国音常用字汇/國音常用字彙), with little fanfare or official announcement. This dictionary was similar to the previous published one except that it normalized the pronunciations for all characters into the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect. Elements from other dialects continue to exist in the standard language, but as exceptions rather than the rule.[39]

After the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China continued the effort, and in 1955, officially renamed guóyǔ as pǔtōnghuà (普通话/普通話), or "common speech". By contrast, the name guóyǔ continued to be used by the Republic of China which, after its 1949 loss in the Chinese Civil War, was left with a territory consisting only of Taiwan and some smaller islands; in its retreat to Taiwan. Since then, the standards used in the PRC and Taiwan have diverged somewhat, especially in newer vocabulary terms, and a little in pronunciation.[40]

In 1956, the standard language of the People's Republic of China was officially defined as: "Pǔtōnghuà is the standard form of Modern Chinese with the Beijing phonological system as its norm of pronunciation, and Northern dialects as its base dialect, and looking to exemplary modern works in báihuà 'vernacular literary language' for its grammatical norms."[41][42] By the official definition, Standard Chinese uses:

- The phonology or sound system of Beijing. A distinction should be made between the sound system of a variety and the actual pronunciation of words in it. The pronunciations of words chosen for the standardized language do not necessarily reproduce all of those of the Beijing dialect. The pronunciation of words is a standardization choice and occasional standardization differences (not accents) do exist, between Putonghua and Guoyu, for example.

- The vocabulary of Mandarin dialects in general. This means that all slang and other elements deemed "regionalisms" are excluded. On the one hand, the vocabulary of all Chinese varieties, especially in more technical fields like science, law, and government, are very similar. (This is similar to the profusion of Latin and Greek words in European languages.) This means that much of the vocabulary of Standard Chinese is shared with all varieties of Chinese. On the other hand, much of the colloquial vocabulary of the Beijing dialect is not included in Standard Chinese, and may not be understood by people outside Beijing.[43]

- The grammar and idiom of exemplary modern Chinese literature, such as the work of Lu Xun, collectively known as "vernacular" (báihuà). Modern written vernacular Chinese is in turn based loosely upon a mixture of northern (predominant), southern, and classical grammar and usage. This gives formal Standard Chinese structure a slightly different feel from that of the street Beijing dialect.

At first, proficiency in the new standard was limited, even among speakers of Mandarin dialects, but this improved over the following decades.[44]

| Early 1950s | 1984 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehension | Comprehension | Speaking | |

| Mandarin dialect areas | 54 | 91 | 54 |

| non-Mandarin areas | 11 | 77 | 40 |

| whole country | 41 | 90 | 50 |

A survey conducted by the China's Education Ministry in 2007 indicated that 53.06% of the population were able to effectively communicate orally in Standard Chinese.[46]

Notes

[edit]language sample

[edit]- inferior accent[2]

- dialects dissappearing[47]

[152] "Russian is increasingly used in most domains of public life and native regional tongues are relegated to use “in the kitchen.” While still widely spoken, languages like Tatar, Udmurt, and Buryat are often dismissed by their speakers as too poor, too colloquial, or otherwise unfit for use outside of the kitchen. As these native languages become restricted to increasingly narrow functional domains, they are popularly referred to as “kuxonnye jazyki,” or “kitchen languages” (Ar-Sergi 2007; Pustai 2005:11; Wertheim 2009:274). experiencing language attrition and shift

[153] Dismissing a code as vernacular by calling it a “kitchen language” is by no means limited to the former Soviet Union. An example often cited in sociolinguistic research is Afrikaans in South Africa, where a whole generation of creative writers has been working to elevate Afrikaans from its status as a “kitchen language” to a language of serious literary production (Barnard 1992; Deumert 2004; Kamwangamalu 2002; Stone 2004). This use of the expression is consonant with a pejorative use of the word kitchen to describe emergent pidgins, which has made its way even into some professional linguists’ work (e.g., Hair 1973:117, regarding a reference to “kitchen pidgin” in Spencer 1971) The Kitchen in Minority-Language Politic

[154] an everyday way of speaking, i.e., a language of daily communication. In fact, what I am calling “kitchen Buryat”—i.e., a colloquial register of Buryat, Buryat as it is spoken in the kitchen—is often referred to by its speakers as bytovoj (everyday or quotidian), which, in itself, does not necessarily constitute a value judgment.

[156] the entire language as an informal code relegated to the domestic sphere (e.g., in discussions of Buryat as a “kuxonnyj jazyk” or “ku:xniin xėlėn”), the word “kitchen” might be invoked to describe one register among many, a variety that is most often spoken in, or is associated with, the domestic sphere (e.g., Buryat as spoken “na kuxne” or “ku:xni soo,” i.e., in the kitchen). Similarly, Afrikaans can be called a kombuis (kitchen) language, as in kombuistaal, or kombuis can be used to refer to vernacular varieties of Afrikaans, as distinct from the suiwer (“pure” or standard) variety (Stone 2004:385). I [48]

Fujianese children’s heritage language was reduced to “kitchen language” that functioned merely to keep the minimum communication between the parents and children going, whereas the more complex, meaningful conversation disappeared in the family.[49]

reduced to be "kitchen languages" that

Russia

[edit]  | |

| Political | |

|---|---|

| Places | |

| People | |

| Miscellaneous | |

U.K. Coronavirus variant[50][51]

U.K. Covid-19 variant[53][54][55][56]

Elo

[edit]Briefing

[edit]

Trump's briefing is the nearly daily briefing on coronavirus pandemic in the United States from March 13, 2020 by the White House Coronavirus Task Force, chaired by President Donald Trump, mostly at the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room, lasting 1 to 2 hours. The format is characterized by being held on a nearly daily basis and at a fixed venue, which was a norm discontinued by the White House from March 11, 2019, almost a year ago. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, on that date, was the last person to chair briefings in such norm.[57] As a result, the coronavirus daily briefings signal the return to the "traditional norms regarding interactions between the White House and the press corps under the Trump administration"[58] The coronavirus daily briefing also raise concerns over the fact that President Trump took the media spotlight away from the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries.[59]

Build up

[edit]Since the Task Force was set up on January 29, 2020, it held briefings from time to time and on varying locations, including outdoor like White House Rose Garden. The task force gradually stepped up the frequency of briefings. On March 6,[57] the briefings shifted to the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room for the first time, yet it was still not held daily until March 13. Up to this point, the briefings were chaired Vice President Mike Pence. From March 13, when the briefing evolved to be on a daily setting, President Donald Trump took charge and chaired the briefings. Note that Trump set up the task force but he himself is not officially part of the task force.

Health precautions in the briefing room

[edit]

From March 16, 2020, yellow signs were taped between an interval of chair by the White House Correspondents' Association (WHCA) to instruct the press corps to seat apart for social distancing reasons. The sign reads "Attention: To ensure proper social distancing this seat is to remain unoccupied for the duration of the coronavirus outbreak. Thank you for your cooperation, WHCA Board."[60] The WHCA has also requested that media outlets maintain "only the bare level of essential staffing".[60] Since then, the distance among the seated press corps and among the standing officials gradually heightened.

Nationwide coverage and ratings

[edit]Mr. Trump and his coronavirus updates have attracted an average audience of 8.5 million on cable news, excluding online streaming. Around half come from Fox News, with the rest shared by CNN and MSNBC.[61] Nielsen ratings

ESPN “Monday Night Football” numbers.[61] Fox News alone akin to the viewership for a popular prime-time sitcom. This past weekend, Fox News recorded its highest weekend viewership since its 2003 coverage of the gulf war.[61] journalists have debated the civic benefits of broadcasting the president’s remarks to the nation with the need to supplement his statements with corrections and context.[61] “Training a camera on a live event, and just letting it play out, is technology, not journalism; journalism requires editing and context,” Mr. Koppel wrote in an email.[61] Network producers and correspondents say there is often some internal debate about whether to carry the president’s appearances live and unfiltered. But given the intensity of the national crisis, many executives have concluded there is no justification for preventing Americans from hearing directly from the president and his health care administrators.[61] “I think the American public — ultimately, they should be the decider,” Trump said at a briefing on a balmy spring evening on March 29 in the Rose Garden, when asked whether networks should carry his remarks live. H

[62] In some ways, Trump’s coronavirus briefings have become his new rallies. His public leadership during the pandemic. Republican pollster Frank Luntz. “Over the last 10 days, I’ve watched him thread that needle between economic concern over the long term and health concern in the short term. “He’s walking the tightrope, but so far so good,”[62]

Trump has found the right balance between the competing demands of the public health crisis and a spiraling economy. a significant portion of the country is looking to Mr. Trump for its facts. A CBS News poll on March 24, 2020 said that 90 percent of Republicans trusted Mr. Trump for accurate information about the pandemic; 14 percent of Democrats said the same.[61]

Journalistic significance

[edit]

In May and June 2019, numerous newspaper wrote news stories about their frustration with the abnormal, adhoc and informal press briefings held in White House driveway drive-by.[63] On January 10, 2019, 13 former White House pressies, foreign service and military officials wrote an open letter to call for the return of regular briefings.[64]It read "Regular briefings also force a certain discipline on government decision making. [...] no presidents want their briefers to say, day after day, we haven’t figured that one out yet.” This open letter in January was widely cited by journalists when reporting the adoption of daily briefings by White House Coronavirus Task Force that came two months after. The media is positive about the move. A journalist commented "Although Trump has made himself the most-available-to-the-press president in the history of the office,[65] his White House driveway drive-bys with reporters have been no substitute for standard pressers. In the driveway drive-bys, Trump sets the agenda, shutting down questions he doesn’t want to explore and babbling on and boasting about subjects more appealing to his self-love. There’s no rigor, no, “I’ll get back to you,” and little edification. In epidemic times like the ones we’re witnessing, the need for a constant and reliable source of information from the government on its policies—and when those policies have changed—has become even more essential."[57] It is commented that "Viewers are relying on that stream of news; they are communing with their president and the federal government in a way we rarely see. [...] The forum allows Trump to speak directly to Americans, unfiltered by the [...] media.", wrote by Liz Peek.[66]

Political impact

[edit]That’s not to say that his appearances are flawless; far from it. They contain far too many instances of Trump tooting his own horn, and also show him sometimes waffling on important issues, such as whether or not to quarantine New York City. [...]But for all the flaws, the public sees a man unquestionably engaged and energized, relentless in his push for solutions.[66] pumping up Trump’s approval ratings. the New York Times, from a “surprising” source — namely, independents and even some Democrats, many of whom did not formerly support the president. The briefings are apparently a revelation to those voters.

the briefings on the coronavirus have relegated Democrats’ favorite agenda items to the back page. Clearly, this pandemic is the story of the day, whether or not the president addresses the nation each afternoon. But having a daily one or two-hour session about therapies and equipment deliveries soaks up a lot of the evening news cycle. That leaves little time to celebrate Greta Thunberg’s latest conquests or the struggles of transgender people, topics that tend to dominate liberal talk shows and newspapers.[66] Such complaints buttress President Trump’s confrontational approach to China, and his calls for U.S. companies to diversify their supply chains. It makes Joe Biden, who frequently admonishes Trump for his “xenophobic” critiques of Beijing, look foolish.[66]

The Hill reports "The crisis has put Trump in the spotlight and sucked oxygen out of the race for the Democratic presidential nomination"[59] “he’s on the news every day. In that sense, the bully pulpit of the White House, that megaphone, is so large that that becomes the campaign,” said Steve Jarding, a Democratic strategist. “That’s the power of incumbency.”“When the other side has to shut down and thinks it’s inappropriate to be out campaigning[59] Ross K. Baker, a professor of political science, “Trump has managed to find a very interesting and politically significant substitute to his rallies,” he said, referring to the daily briefings of the White House coronavirus task force, which Trump leads. “It’s for many people a time of day when they tune in to hear the president. They’re not tuning in to hear Joe Biden or Bernie Sanders,”[59]

Some Democrats are now trying to pressure television networks to stop covering Trump’s briefing. Jon Favreau, Obama’s former speechwriter, and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee wrote an email to supporters Tuesday arguing “there is zero reason to give the president a free campaign commercial every day where he’s free to spread lies that put people’s lives at risk.” Favreau noted that MSNBC host Chris Hayes has refused to play audio of Trump’s briefings and the local NPR station in Seattle has decided not to air the president’s briefings.[59]

Anonymous senator "As a candidate, you don’t want to undermine people working together,” the senator said[59] Ratings[67]

Reception

[edit]On President Trump

[edit]By the press

[edit]President Trump's self-portrayal as wartime presidents on March 18 attracted much sarcastic commentary from the media outlets. [68]Many media criticized Trump downplayed the pandemic early on and gave a false positive impression to the country. The New York Times, in parcitular, wrote an news analysis that rediculed Trump of "rewriting of history" because Trump's early downplaying does not seem to be at a "war", which undercut his own war president narrative. The White House press corps of these media highlighted this issue by reading past tweets of Trump to his face in the press briefing. Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of Annenberg Public Policy Center at University of Pennsylvania, says that President Trump benefited from a halo effect by having "two very credible health experts standing up there" next to him.

By independent voters

[edit]she also saw flashes of empathy, a trait many critics find lacking in Mr. Trump.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/us/politics/trump-approval-rating.html

Who Are the Voters Behind Trump’s Higher Approval Rating?

Trip Gabriel and Lisa LererMarch 31, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/us/politics/trump-approval-rating.html

On other officials

[edit]Dr. Anthony Fauci is widely praised for his clarity and willingness to correct President Trump's statement.

Vice President Mike Pence is praised for his calmness and for bringing back the old-fashioned White House press secretary-style of press briefing.[57]

On the media

[edit]The clamor to boycott the president’s briefings violates the basic journalistic rule to be where the action is.[69]

Leading the pack of objectors are journalist James Fallows and J-school prof Jay Rosen, who would have the cable networks stop airing Trump’s briefings live because they’re unfiltered propaganda.[69] Meanwhile, journalist Jonathan Alter and broadcaster Soledad O’Brien want the political press corps [reporters], which ordinarily dominate the briefings, to step aside and let science and health reporters take the lead in questioning the president at these briefings.[69]

CNN fact check the lies and obfuscations[69] He speaks and political markets shudder. Even when he holds his tongue—a rare occurrence for our current president, I’ll admit—the world shifts. Like it or not, his lies move markets, too, and it’s part of journalists’ job to cover those, too. Journalists are supposed to bear witness, not avoid witnessing. For the Washington Post and New York Times to put the backs of their hands to their foreheads and say they can’t bear reporting from these White House briefings because they don’t contain enough news—or because the virus makes them too dangerous to attend—are abrogating their duties.[69]

Coronavirus is poised to become the story of the century and the Times and the Post think it makes sense for their reporters to dodge the public, presidential side of the story[69]

What they worry about the most is that the average viewer will be sucked in by Trump’s lies. This paternalistic mindset holds that the same individual who can be trusted to vote in elections can’t be trusted on his own to listen to long, unbroken statements from the president.[69]

incredibly self-serving and very long—most Hollywood movies run shorter than Trump’s March 31 briefing, which clocked in at 2 hours 11 minutes.[69]

state propaganda (2017 January)[69]

Timeline of major contents at briefings

[edit]The coronavirus task force briefings at the White House have become Trump’s primary vehicle for getting his message out to Americans each day. He’s used them to announce national guidelines on social distancing, to say he would use the Defense Production Act to marshal the private sector to manufacture supplies, to position himself as a “wartime president,” and to respond to widespread criticisms that his Administration was woefully unprepared to fight the virus and fumbled its initial response on testing and other measures.[62]

- March 16: The U.S. government for the first time released social distancing guidelines, which is advised to be a 15-day period.[70]

- March 18: Trump announced to invoke the Defense Production Act to make military resources available. In relation to the DPA, he framed the fight against the pandemic as a war by referencing the country’s mass mobilization and shared sacrifice during World War II. The March 18 briefing is widely highlighted by the Trump's remark that “I view it as a, in a sense, a wartime President, [...] It's a medical war.” [71]

- March 31: The U.S. government for the first time release the much-anticipated modelling figures for the fatalities in the U.S. pandemic.[70] It is projected if everything possible is done, deaths would be between 100,000 and 240,000 Americans die; while if the country "just ride it out" and do not take any measures of mitigation, deaths would be between 1.5 and 2.2 million. The media described the figure as "grim" and often quoted Trump's remarks on March 31 that "This is going to be a very, very painful two weeks.[72]

References

[edit]- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jeff Siegel 2003was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Ying-Chuan Chen2013was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Huang, Tsan (2004). Language-specificity in Auditory Perception of Chinese Tones (Thesis). Ohio State University.

an AX discrimination task with an inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of 300ms and natural speech Putonghua (Standard Beijing Mandarin) tones where the T214 sandhi rule (/T214.T214/ -> [T35.T214]) was found to contribute to the warping of the Chinese listeners' tone space, [...]

- ^ a b c d e Zhang, Qing (2018). "Chapter 0.4 Clarification of Terms". Language and Social Change in China: Undoing Commonness through Cosmopolitan Mandarin. New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b Coblin, W. South (2000). "A Brief History of Mandarin". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 120 (4): 539-541.

- ^ Sanders, Robert M. (1987). "The Four Languages of "Mandarin"" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-07.

- ^ Shen, Zhongwei (2020). A Phonological history of Chinese. p. 181-182.

- ^ a b c d Mair (2013), p. 737.

- ^ a b Coblin (2000), p. 537.

- ^ Mair (1991), pp. 11–12.

- ^ 史皓元 (2018). "再谈东北方言与北京方言的关系——基于移民史和入派三声的考量". 语言学论丛 (2). Translated by 单秀波: 21,24,25.

- ^ 曾晓渝; 陈希 (2017). "云南官话的来源及历史层次" [The source and historical strata of Yunnan Mandarin dialects] (PDF). 中国语文 (2): 182-192. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-07.

- ^ a b Zeng, Xiaoyu (June 2018). "A case study of dialect contact of early Mandarin". Lingua. 208: 31-43. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2018.03.004. An earlier version in Chinese by the same author, see 曾晓渝 (2013). "明代南直隶辖区官话方言考察分析". 古汉语研究 (4).

- ^ 邓彦 (2017). 贵州屯堡话与明代官话比较研究 (monograph). 南京师范大学出版社. p. 1-396.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 136.

- ^ "Mandarin". Oxford Dictionary.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Weng, Jeffrey 2018 611–633was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ 张杰 (2012). "论清代满族语言文字在东北的兴废与影响". In 张杰 (ed.). 清文化与满族精神 (in Chinese). 辽宁民族出版社. Archived from the original on 2020-11-05.

[天聪五年, 1631年] 满大臣不解汉语,故每部设启心郎一员,以通晓国语之汉员为之,职正三品,每遇议事,座在其中参预之。

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 133–134.

- ^ 朱文熊 (1906). 江苏新字母 [Jiangsu New Alphabets]. p. Preface.

余学普通话(各省通行之话),虽不甚悉,然余学 此时所发之音,及余所闻各省人之发音,此字母均能拼之,无不肖者。

As cited in "江苏新字母·前言". 清末文字改革文集. 北京: 文字改革出版社. 1958. p. 60. As cited in 李宇明 (2003). "清末文字改革家论语言统一". 语言教学与研究 (2). - ^ "普通话这个词的来历" [The Origin of the word Pǔtōnghuà]. 语文现代化 (2): 186. 1980.

- ^ 杨慧 (2009). ""普通 "的微言大义——"文化革命"视域下的瞿秋白"普通话"思想" (PDF). 社会科学辑刊 (3): 192 (note 1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-26.

- ^ 曹德和 (2011). "恢复"国语名"称的建议为何不被接受_──《国家通用语言文字法》学习中的探讨和思考". 社会科学论坛 (in Chinese) (10).

- ^ Yuan, Zhongrui. (2008) "国语、普通话、华语 Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Guoyu, Putonghua, Huayu)". China Language National Language Committee, People's Republic of China

- ^ Sponsored by Council of Indigenous Peoples (2017-06-14). 原住民族語言發展法 [Indigenous Languages Development Act]. Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China, the Ministry of Justice.

Indigenous languages are national languages. To carry out historical justice, promote the preservation and development of indigenous languages, and secure indigenous language usage and heritage, this act is enacted according to... [原住民族語言為國家語言,為實現歷史正義,促進原住民族語言之保存與發展,保障原住民族語言之使用及傳承,依...]

- ^ a b 王保鍵 (2018). "客家基本法之制定與發展:兼論 2018 年修法重點" (PDF). 文官制度季刊. 10 (3): 89, 92-96. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-05.

- ^ Sponsored by Hakka Affairs Council (2018-01-31). 客家基本法 [Hakka Basic Act]. Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China, the Ministry of Justice.

Hakka language is one of the national languages, equal to the languages of other ethnic groups. The people shall be given guarantee on their right to study in Hakka language and use it in enjoying public services and partaking of the dissemination of resources. [客語為國家語言之一,與各族群語言平等。人民以客語作為學習語言、接近使用公共服務及傳播資源等權利,應予保障。]

- ^ Mair (1991), pp. 11.

- ^ a b 許維賢 (2018). 華語電影在後馬來西亞:土腔風格、華夷風與作者論. 台灣: 聯經出版. p. 36-41.

- ^ Kane, Daniel (2006). The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 22–23, 93. ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5.

- ^ Translation quoted in Coblin (2000), p. 539.

- ^ Liberlibri SARL. "FOURMONT, Etienne. Linguae Sinarum Mandarinicae hieroglyphicae grammatica duplex, latinè, & cum characteribus Sinensium. Item Sinicorum Regiae Bibliothecae librorum catalogus" (in French). Liberlibri.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Coblin (2000), pp. 549–550.

- ^ L. Richard's comprehensive geography of the Chinese empire and dependencies translated into English, revised and enlarged by M. Kennelly, S.J. Archived 26 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Shanghai: T'usewei Press, 1908. p. iv. (Translation of Louis Richard, Géographie de l'empire de Chine, Shanghai, 1905.)

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 134.

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 18.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 10.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 15.

- ^ Bradley (1992), pp. 313–314.

- ^ "Law of the People's Republic of China on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language (Order of the President No.37)". Gov.cn. 31 October 2000. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

For purposes of this Law, the standard spoken and written Chinese language means Putonghua (a common speech with pronunciation based on the Beijing dialect) and the standardized Chinese characters.

Original text in Chinese: "普通话就是现代汉民族共同语,是全国各民族通用的语言。普通话以北京语音为标准音,以北方话为基础方言,以典范的现代白话文著作语法规范" - ^ Chen (1999), p. 24.

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Chen (1999), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Chen (1999), p. 28.

- ^ "More than half of Chinese can speak Mandarin". Xinhua. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

D.Bradley2008was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Graber, Kathryn E. (2017). "The Kitchen, the Cat, and the Table: Domestic Affairs in Minority‐Language Politics". Linguistic Anthropology. 2 (2): 152. doi:10.1111/jola.12154.

- ^ 张东辉 (2010). "Language Maintenance and Language Shift Among Chinese Immigrant Parents and Their Second-Generation Children in the U.S.". Bilingual Research Journal (33): 55. doi:10.1080/15235881003733258.

- ^ "How Worried Should We Be About The New U.K. Coronavirus Variant?". npr. Washington, D.C. 2020-12-24.

- ^ "The U.K. Coronavirus Variant: What We Know". New York Times. 2020-12-21.

- ^ "UK coronavirus variant may be more able to infect children: scientists". Reuters. London. 2020-12-22.

- ^ "Joint statement on first COVID-19 U.K. variant case in B.C. (press release)". British Columbia government news. 2020-12-27.

- ^ "Ontario identifies 1st cases of COVID-19 variant detected in the U.K." Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2020-12-27.

First cases of U.K. COVID-19 variant found in Canada (...) Ontario identifies U.K. COVID-19 variant in province (...) vaccines that use mRNA technology can be reverse engineered quite quickly to take on variants — such as the recent U.K. variant of the coronavirus

- ^ "UK COVID-19 variant detected in Israel, health ministry says". Reuters. London. 2020-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "UK to ban travel from South Africa over new variant; Canada approves Moderna vaccine - as it happened". The Guardian. London. 2020-12-24.

Northern Ireland has confirmed a case of the new UK Covid-19 variant

- ^ a b c d Jack Shafer (2020-03-10). "Make Mike Pence the New White House Press Secretary". Politico magazine (opinion).

- ^ Rashaan Ayesh (2020-03-11). "It's been a year since the last daily White House press briefing". Axios (website).

- ^ a b c d e f Alexander Bolton (2020-04-01). "Coronavirus crisis scrambles 2020 political calculus". The Hill.

- ^ a b Betsy Klein (2020-03-16). "White House reporters practice social distancing in the briefing room". CNN.

- ^ a b c d e f g Michael M. Grynbaum (2020-03-25). "Trump's Briefings Are a Ratings Hit. Should Networks Cover Them Live?". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Tessa Berenson (2020-03-30). "'He's Walking the Tightrope.' How Donald Trump Is Getting Out His Message on Coronavirus". TIME magazine.

- ^ Paul Farhi (2019-06-02). "Driveway drive-bys: With formal briefings long gone, Trump's aides meet the press (briefly) in an unusual spot". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2020-04-01.

- ^ 13 former White House press secretaries, foreign service and military officials (Richard Boucher, Nicholas Burns, Jay Carney, Victoria Clarke, Robert Gibbs, John Kirby, Joe Lockhart, George Little, Scott McClellan, Michael McCurry, Dee Dee Myers, Jen Psaki, Jake Siewert) (2020-01-11). "Why America needs to hear from its government". CNN (opinion).

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Erik Wemple (2019-08-15). "President Trump eclipses his predecessors on media availability". Washington Post (opinion).

- ^ a b c d e Liz Peek (2020-04-02). "5 reasons Democrats fear Trump's coronavirus briefings". The Hill (opinion).

- ^ Chris Cillizza (2020-03-30). "The deep leadership flaw revealed by Trump touting his coronavirus press conference ratings". CNN (opinion).

- ^ Annie Karni, Maggie Haberman and Reid J. Epstein (2020-03-22). [www.nytimes.com/2020/03/22/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-wartime-president.html "'Wartime President'? Trump Rewrites History in an Election Year"]. New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jack Shafer (2020-04-01). "When It Comes to Trump, Media Shouldn't Keep Its Distance". Politico magazine (opinion).

- ^ a b Nurith Aizenman (2020-04-01). "5 Key Facts Not Explained In White House COVID-19 Projections". NBC news.

- ^ Brian Benett and Tessa Berenson (2020-03-19). "'Our Big War.' As Coronavirus Spreads, Trump Refashions Himself as a Wartime President". TIME magazine.

- ^ Denise Chow (2020-04-01). "What we know about the coronavirus model the White House unveiled". NBC news.

cindy dock

[edit]

Cindy Dock (born c. 1977)[3] is a former Australian tennis player active at the ITF Women's Circuit level from December 1995 to January 1998, career-high ranked at 574 in singles (on October 13, 1997) and at 386 in doubles (on February 23, 1998).[4] She is of Asian Australian ancestry.

Cindy and her fellow family member Kerry Dock, are mostly known for being the first coach of Alex de Minaur back in the early 2000s, as Minaur achieved Grand Slam successes from 2019.[5][6]

Career matches

[edit]Cindy Dock is from Strathfield, New South Wales, Australia. During her professional career from December 1995 to January 1998, she mostly played in tournaments held domestically in Australia. She had better success in doubles.[7]

In singles, she consistently played in ITF Women's Circuit $10,000-category, reaching as far as quarterfinal in Warwick, Queensland, Australia, April-May 1997.[7]

In doubles, the highest category she played was the ITF Women's Circuit $50,000-category, which she reached once, held in Thessaloniki, Greece, September 1997. She and her fellow Australian partner Vanessa Kendall reached the first round in Thessaloniki's main draw.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^

{{cite news}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite news}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Exact birth year unknown, yet she is stated to be aged 43 in 2020 on her official profile on International Tennis Federation. For reference, see ITF 2020.

- ^ "Cindy Dock, Ranking History, Weekly & Yearly Rankings". WTA. Archived from the original on 2020-09-12.

- ^ "Rising Aussie tennis star Alex De Minaur is a demon on the court". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Bossi, Dominic (2020-09-08). "'The perfect student': De Minaur's rise from Carss Park to a grand slam quarter-final". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-09-12.

- ^ a b c "Cindy Dock Women's Singles Activity". ITF. Archived from the original on 2020-09-12.

Related articles

[edit]https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/trump-branded-coronavirus-mailer https://web.archive.org/save/https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/trump-branded-coronavirus-mailerTrump-Branded Mailer Of Coronavirus Guidance Crops Up In California Kate Riga|March 23, 2020

Trump-branded coronavirus government mailing spurs criticismUpdated Mar 27, 2020; Posted Mar 27, 2020

This is the real problem with the Trump flyer. He's so distrusted, with such a consistent record of lying, most people won't read take it seriously. If this had read, Dr. Fauci's Guidelines, or Dr. Acton's, people would pay far more attention.

President Trump’s Coronavirus Guidelines for America[1]: The task force briefings aren’t the only way Trump is sending powerful messages about his actions on stemming the coronavirus pandemic to the American public, Jamieson says. Americans received a note in the mail last week outlining the national social distancing guidelines put in place on March 16: On one side, the card announces these are “President Trump’s Coronavirus Guidelines for America,” and on the other, the guidelines are listed. The mailers were sent starting March 21 to every residential location across the United States, including P.O. boxes— or 130 million pieces in all, a spokesperson for the United States Postal Service told TIME.“One side of this is a federally funded campaign ad for Donald Trump,” says Jamieson. “The other side is extraordinarily useful information being sent to us by the CDC.” The White House confirmed to TIME that the cards were sent jointly by the White House and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); a spokesperson for the CDC said the content of the mailers was created in consultation between CDC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Dr. Birx through the White House task force.“People picked up this postcard today and saw, ‘President Trump sent me something to protect me,’” Jamieson says. “The most effective persuasion is persuasion that doesn’t look like persuasion.”