User:Jordanroderick/sandbox

The steamship Mobile was steel-hulled freighter built for the Atlantic Transport Line in 1891. She carried live cattle and frozen beef from the United States to England until the advent of the Spanish-American War. In 1898 she was purchased by the United States Army for use as an ocean-going troopship. During the Spanish-American War she carried troops and supplies between the U.S. mainland, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

After the war, she was renamed USAT Sherman and was fitted for service in the Pacific, supporting U.S. bases in Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines. In addition to her regular supply missions, she transported American troops to several conflicts in the Pacific, including the Philippine Insurrection, the 1911 Revolution in China, and the Siberian Intervention of World War I. Her last sailing in government service was in March 1921.

Construction and characteristics

[edit]The Atlantic Transport Line commissioned four sisterships to be built by the Harland and Wolff Shipyard in Belfast, Northern Ireland. They were, in order of launch, Massachusetts, Manitoba, Mohawk, and Mobile.[1]

Mobile's hull was built of steel plates. She was 445.5 feet (135.8 m) long, with a beam of 49.2 feet (15.0 m) and a depth of hold of 30 feet (9.1 m). Her gross register tonnage was 5,283, and her net register tonnage was 3,725.[2] She displaced 7,271 tons.[3]

She was driven by two manganese-bronze propellers.[4] These were turned by two triple-expansion steam engines which were also built by Harland and Wolff. They had high, medium, and low-pressure cylinders with diameters of 22.5 inches, 36.5 inches, and 60 inches, respectively, with a stroke of 48 inches. Each of the engines was rated at 600 horsepower.[2] Steam was provided by two coal-fired boilers. At full speed she would burn 60 tons of coal per day.[5]

Massachusetts' cargo capacity was built primarily to support the shipment of American beef to England, both in the form of live cattle and refrigerated dressed beef. She was fitted out to transport 1,000 live cattle,[6] and could carry 1,000 tons of fresh meat in her refrigerated holds.[7][5] She was also fitted with a salon and first-class cabins for 60 passengers.[8]

Mobile was launched from the Harland and Wolff shipyard on Queen's Island on 17 November 1892.[4] She then had her engines and boilers installed. The ship was completed on 27 July 1893.[3]

Atlantic Transport Line Service (1892–1898)

[edit]While the Atlantic Transport Line was controlled by American shipping magnate Bernard N. Baker, its operations were run from Britain. Mobile's home port was London and she was registered as a British ship.[2] During her six-year career with Atlantic Transport Line she was assigned to the New York to London route.[9] Mobile completed her maiden voyage to New York on 6 August 1893.[8]

Massachusetts proved exceptionally capable at moving cattle across the Atlantic. In the first half of 1892, on her first few crossings, she brought 998 cattle to England and only two died en route.[10] Since horses could be shipped using the same facilities as cattle, Massachusetts occasionally shipped horses across the Atlantic.

On 20 September 1894, Mobile went aground in the Thames while proceeding to London.[11]

US Army Service (1898–1922)

[edit]Spanish–American War service (1898–1899)

[edit]

On 25 April 1898, Congress declared war on Spain, beginning the Spanish-American War.[12] An immediate objective was to defeat Spain in the Caribbean, taking Cuba and Puerto Rico. At the time, the United States had few overseas possessions, and thus its military had limited ocean-capable sealift to support such an offensive. American political leaders preferred to acquire American ships to support the war effort, rather than enrich foreigners and rely on foreign crews. There were also legal constraints on using neutral-flagged vessels in American military operations. Through some quirks in the Congressional funding of the war, the US Navy was able to charter transport ships prior to the declaration of war and tied-up the best of the American merchant fleet for its use. When the Army was able to begin acquiring ships after the declaration of war, fewer domestic options remained. While the Atlantic Transport Line was British-flagged, it was American owned, making it a more attractive option.[10]

Army Colonel Frank J. Hecker approached the Atlantic Transport Line to charter its fleet, and was refused. He then offered to buy the vessels he sought and a deal was struck, subject to the approval of the Secretary of War Russel Alger. In addition to Mobile, the Atlantic Transport Line sold Manitoba, Mohawk, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, and Minnewaska.[5] These ships were placed under the Quartermaster's Department of the United States Army. The Army reckoned Mobile's capacity to be 80 officers, 1,000 men, and 1,000 horses. Mobile arrived in New York from London on her last trip for the Atlantic Transport Line on 6 July 1898. She was turned over to the Army as soon as she was unloaded.[13] The purchase price of the ship was $660,000.[6]

Mobile underwent little conversion for military use. She sailed from New York on 14 July 1898 for Charleston, South Carolina, where she arrived on 18 July 1898.[14] By that time the fighting was all but over. Hostilities ceased on 12 August 1898.[15] Even though the war was over, the Army faced substantial logistical challenges. It had to garrison the new possessions, and return the men temporarily mobilized for the offensive. Mobile moved thousands of troops and animals to and from Cuba and Puerto Rico in the immediate post-war period.

| Departure | From | To | Arrival | Units embarked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 July 1898[6][16] | Charleston | Ponce | 2 companies, 6th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment

16th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment | |

| 13 August 1898[17][18] | Santiago | Montauk, New York | 18 August 1898 | 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment |

| 16 February 1899 | Savanah | Matanzas |

Preparation for Pacific service (1899)

[edit]

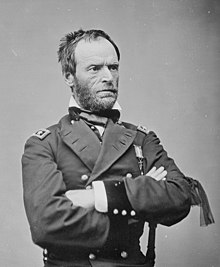

Having taken Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, the Army had a permanent need for transport to overseas bases. The annexation of Hawaii in 1898 also required new ocean transport. The Army Transport Service chose the best vessels acquired during the war to become a permanent sealift capability. Massachusetts and her three sister ships were retained for this purpose. To mark their transition to permanent military service, they were renamed in January 1899. Massachusetts became United States Army Transport Sheridan, named for Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman.[3]

On 19 February 1899, Sheridan sailed from New York, bound for Manila, via the Suez Canal.[19] She had a full load, including the 12th Infantry Regiment, the 3rd battalion of the 17th Infantry Regiment,[20] 2,300 shells for field artillery, several hundred thousand rounds of small arms ammunition, and tons of other cargo.[21] Her passengers included 57 officers, 1,796 enlisted men, and 56 women and children, family members of the troops.[22] She stopped at Gibralter for water and coal in March 1899, but due to a measles outbreak on board was held in quarantine.[23] She stopped at Malta a few days later to give the troops some time beyond the crowded confines of the ship. A review of the nearly 2,000 American soldiers by Sir Francis Grenfell, Governor of Malta, and Admiral Sir John Ommaney Hopkins, Commander-In-Chief of British naval forces in the Mediterranean was organized.[24] Sheridan reached Port Said on 16 March 1899,[25] Colombo by 1 April,[26] Singapore on 10 April,[27] and finally arrived in Manila on 15 April 1899.[22]

After disembarking her troops and unloading her cargo in Manila, she sailed to San Francisco on 22 April 1899. Sheridan had on board the remains of 18 soldiers who had died in the Philippines,[28] and 103 soldiers, discharged soldiers, and soldiers' family members. She arrived at her new home port, via a coaling stop in Nagasaki, on 22 May 1899.[29]

As configured for her Pacific service, Sheridan's authorized complement was 13 officers and 172 crew.[30] As she sailed, her crew was typically between 175 and 200 officers and men.[31][32][33]

Philippine Insurrection (1899–1900)

[edit]Sheridan had a quick shipyard visit in San Francisco to repair boiler problems,[34] and then began preparing for her next trip to Manila. There was an urgent need for troops and supplies in the Philippines to prosecute American goals in the Philippine-American War. Sheridan was in almost constant motion in a variety of roles. In November 1899, for instance, she acted as an assault transport, landing troops at Lingayen Gulf to cut off an insurgent retreat.[35] Details of Sheridan's trans-Pacific trips during this period are shown in the table below.

| Departure | From | To | Arrival | Units Embarked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 June 1899[36] | San Francisco | Manila | 24 July 1899 | Troops A & F 4th Cavalry Regiment

Companies D & H 14th Infantry Regiment 1,248 unassigned troops |

| 10 August 1899[37] | Manila | San Francisco | 7 September 1899[38] | 1st South Dakota Volunteer Infantry Regiment (667 men)

13th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment (996 men) 205 discharged troops |

| 30 September 1899[39] | San Francisco | Manila | 27 October 1899[40] | 33rd Volunteer Infantry Regiment

3 companies 32nd Volunteer Infantry Regiment |

| 9 November 1899[41] | Manila | San Francisco | 5 December 1899 | 3 passengers |

| 17 January 1900[42] | Tacoma | Manila | 10 February 1900[43] | Hay, meat, supplies |

| 6 March 1900 | Manila | San Francisco | 1 April 1900[44] | 264 Army & Navy sick, discharged, and prisoners |

Pacific service (1900–1918)

[edit]In April 1900, Sheridan was pulled out of service to undergo a substantial refit at the Fulton Iron Works in San Francisco. The electric light and refrigeration plants were rebuilt, decks were rebuilt and strengthened, staterooms were added for both passengers and ships' officers, the dining salon was extended, and numerous other improvements accomplished.[45] The cost of this work was $339,169.[46] Her first sailing after the overhaul left San Francisco on 17 November 1900 with roughly 400 personnel bound for Manila.[47]

Sheridan began a regular shuttle service between San Francisco, Honolulu, Guam, and Manila. The Army Transport Service maintained a roughly monthly schedule of sailings from San Francisco using Sheridan, USAT Logan, USAT Sherman, and USAT Thomas. The ships carried supplies, cash,[48][49] and fresh troops to the Philippines, and relieved, discharged, wounded, and dead troops back to the United States.[50] Many officers brought their wives and children aboard as cabin passengers.[51] In addition to Army personnel, the ship also routinely transported U.S. Marines, and U.S. Navy personnel.[52]

The first-class service offered to Sheridan's cabin passengers attracted many notables, including Governor-General of the Philippines Arthur MacArthur jr.,[53] Major General Adolphus W. Greely, commander of the Army Signal Corps,[54] Major Generals John F. Weston,[55] Arthur Murray,[56] and Lloyd Wheaton,[57] Brigadier Generals John C. Bates, Frederick D. Grant,[58] and Frederick Funston,[59] and Inspector General Peter D. Vroom.[60] Another set of notable passengers were several hundred Philippine Scouts and Manila constabulary who participated in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904.[61][62]

Sheridan continued her regular Pacific crossings until September 1905 when she went to the Union Iron Works in San Francisco for an overhaul.[63] Her first sailing for Manila after the overhaul left San Francisco on 26 January 1906 with the 24th Infantry Regiment embarked.[64]

Allied Expeditionary Force Siberia (1918–1920)

[edit]The revolutionary Bolshevik government of Russia made a separate peace with the Central Powers in March 1918, ending Russian participation in World War I. Sheridan's first trip to Siberia evacuated Maria Bochkareva, who led a Russian military unit fighting the Bolsheviks, from Vladivostok on 18 April 1918.[65][66]

In July 1918, President Wilson sent U.S. troops to Siberia as part of an Allied Expeditionary Force to safeguard American interests threatened by Russia's withdrawal from the war. Sheridan and sister-ship USAT Logan reached Vladivostok on 29 September 1918. They disembarked 3,682 troops, which brought the previously landed 27th and 31st Infantry Regiments to full strength.[67]

During 1919 Sheridan sailed a triangular route between San Francisco, Vladivostok, and Manila, with her usual intermediate stops in Hawaii, and Guam.[68][69] While in 1918, the ship brought troops to Vladivostok, by late 1919 she was bringing them home. She arrived in San Francisco on 7 December 1919 with 1,700 men of the expeditionary force.[70]

Sherman's final trip for the Army was a round trip to the Philippines. She arrived back at San Francisco on 6 June 1922.[71]

Los Angeles Steamship Company (1922–1933)

[edit]In December 1920, the War Department announced its intention to sell eight Army transports, including Sherman and her three sister-ships purchased from the Atlantic Transport Line in 1898.[72] Given the glut of more modern troopships built during World War I, it made little sense for the Army to maintain the thirty-year-old Sherman. Sealed bids for Sherman and several other transports were opened and accepted on 2 October 1922.[73] Sherman was sold to the Los Angeles Steamship Company, which intended to sail her between Los Angeles and Honolulu. She was a replacement for the company's City of Honolulu which burned at sea.[74]

The Los Angeles Steamship Company was reported to have spent $250,000 to $300,000 refitting the ship for her new service.[75] The major work was done at the Los Angeles Shipbuilding and Drydock Company.[76] Among the changes were to convert her boilers from burning coal to burning oil. Her name was changed to Calawaii, a contraction of California and Hawaii, the two endpoints of her route.[77] The interiors of her staterooms and lounges were replaced as was her galley. New linens and china were procured.[78]

Her top deck, the promenade deck, contained 23 staterooms, the doctor's office, music room, and smoking room. Her second deck contained 51 staterooms, the beauty salon, dining salon, and barber shop. Her third deck, the main deck, contained another first-class dining salon, and five 4-person third-class staterooms with an attached dining area. Her fourth deck contained another 14 staterooms and a lounge.[79] She sailed with as many as 418 passengers.[80] The passenger accomodations left plenty of room for freight, and Calawaii sailed with as much as 6,000 tons aboard. From Hawaii to the mainland, much of the freight was pineapples and bananas.[81] From California to Hawaii freight ran the gamut from new cars for auto dealers, airplanes for the Navy, cement, asphalt, pipe, tile, grain, oranges, live quail, mail and to much more besides.[82][83][84]

Calawaii's maiden voyage to Honolulu left Los Angeles on 10 February 1923. She averaged 13.8 knots en route. [85] She returned to Los Angeles on 3 March 1923 with 125 passengers and a cargo of fresh and canned pineapples and bananas.[86] The ship sailed one roundtrip per month, alternating with another company ship to provide sailings every two weeks in both directions.[87] In 1926 the minimum one-way fare on Calawaii was $90.[88]

In October 1929 the ship went into drydock to install new propellers which were intended to increase her speed. A new cafe on the promenade deck was added, and the smoking room was doubled in size at the same time.[89][90]

In early 1932 some juggling of the company's transpacific schedule left Calawaii out of commission for four weeks. The location department of Warner Brothers took advantage of the gap in her sailings to charter the ship for six days of shooting for the movie One Way Passage, starring William Powell and Kay Francis.[91]

The Los Angeles Steamship Company and Matson Navigation Company agreed to merge in October 1931. Both companies competed for passengers and freight between California and Hawaii, raising the possibility of cost cutting consolidation as the Great Depression deepened. In the immediate aftermath of the merger, Calawaii continued to sail for the now, wholly-owned subsidiary Los Angeles Steamship Company.[92] In June 1932 Matson announced that two of the Los Angeles Steamship Company liners, including Calawaii, would be retired.[93]

Calawaii was sold to Kishimoto Kisen Kaisha of Japan to be scrapped. She sailed from Los Angeles for the final time on 27 August 1933.[94] She arrived in Osaka on 25 September 1933.[95]

References

[edit]- ^ "New Transatlantic Line Of Steamers". Belfast News-Letter. 30 September 1891. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Vol. 1 - Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register. 1893.

- ^ a b c Clay, Steven E. U.S. Army Order Of Battle 1919-1941 (PDF). Vol. 4. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 2179.

- ^ a b "Launches In Belfast". Belfast News-Letter. 18 November 1892. p. 7.

- ^ a b c "Expedited Ship Buying". The Sun. 25 June 1898. p. 2.

- ^ a b c United States Commission Appointed by the President to Investigate the Conduct of the War Department in the War with Spain. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1900. pp. 136, 175.

- ^ "May Attach U.S. Ships". New York Times. 9 July 1898. p. 12.

- ^ a b "New Cargo And Passenger Steamer". The Sun. 7 August 1893. p. 6.

- ^ "The Fast Freight Steamer Mobile". Times-Democrat. 10 August 1893. p. 7.

- ^ a b Kinghorn, Jonathan (2012-01-27). The Atlantic Transport Line, 1881-1931: A History with Details on All Ships. McFarland. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7864-8842-1.

- ^ "Steamer Mobile Aground". Evening World. 20 September 1894. p. 1.

- ^ "The Declaration Of War". New York Times. 26 April 1898. p. 3.

- ^ "The Troopships". Los Angeles Times. 7 July 1898. p. 3.

- ^ "No. 31 at Charleston". Birmingham Post-Herald. 18 July 1898. p. 2.

- ^ "Protocol of Peace -- Aug 12, 1898". web.archive.org. 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2024-06-25.

- ^ The United States Army and Navy Journal and Gazette of the Regular and Volunteer Forces. Army and Navy Journal Incorporated. 30 July 1898. p. 993.

- ^ "To Start Today". Boston Globe. 13 August 1898. p. 12.

- ^ "2d Ashore". Boston Globe. 19 August 1898. p. 5.

- ^ "To Reinforce Gen. Otis". Evening Star. 31 January 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "The Sheridan Gets Away". The New York Times. 20 February 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "To Reduce The Tropic Islands". Buffalo News. 18 February 1899. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Transport Sheridan Arrives". Minneapolis Daily Times. 15 April 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "At Gibralter". Cincinnati Enquirer. 4 March 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "A Notable Occurrence". Unionville Republican. 15 March 1899. p. 3.

- ^ "American Control Almost Complete". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 16 March 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Oil Will Continue Activity". Buffalo News. 1 April 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Vessels Reach Singapore". Green Bay Press-Gazette. 10 April 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Bodies Returned For Burial". Omaha Evening Bee. 25 May 1899. p. 2.

- ^ "Home From Manila". Los Angeles Times. 23 May 1899. p. 2.

- ^ Merchant Vessels Of The United States (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1914. p. 445.

- ^ "Philippine Islands: Review of Plague and Its Causes in Japan". Public Health Reports (1896-1970). 21 (17): 426–429. 1906. ISSN 0094-6214.

- ^ "Philippine Islands: Report from Manila. Smallpox. Status of Cholera in the Provinces. Recrudescence of Cholera in Bohol and Negros Occidental. Examination of Cholera Carriers. Inspection of Vessels". Public Health Reports (1896-1970). 24 (20): 659–660. 1909. ISSN 0094-6214.

- ^ "Philippine Islands: Reports from Manila. Cholera and Smallpox. Cholera in the Provinces. Inspection of Interisland Vessels Discontinued. Inspection of Vessels. Quarantine Transactions, Month of May, 1908". Public Health Reports (1896-1970). 23 (32): 1147–1149. 1908. ISSN 0094-6214.

- ^ "Sheridan Disabled". Los Angeles Times. 2 June 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Advance Of Troops Reported By Otis". San Francisco Call and Post. 7 November 1899. p. 11.

- ^ "The Latest From Manila". Evening Mail. 24 July 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Day Of Reconnoissance". Los Angeles Times. 11 August 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Northern Fighters Home From The Front". San Francisco Call and Post. 8 September 1899. p. 12.

- ^ "Sheridan Sails Saturday". San Francisco Examiner. 30 September 1899. p. 5.

- ^ "Cablegrams From Otis". Los Angeles Times. 28 October 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Transport Sheridan In". Los Angeles Times. 6 December 1899. p. 1.

- ^ "Carries Supplies To Manila". San Francisco Chronicle. p. 2.

- ^ "The Resolute Is All Right". News-Journal. 20 February 1900. p. 4.

- ^ "Transport Sheridan Comes". Los Angeles Times. 2 April 1900. p. 2.

- ^ "Renovated Transport Sheridan Sails For Manila With Recruits For Army". San Francisco Call and Post. 17 November 1900. p. 7.

- ^ "Navy Yard Beats Private Bidders". San Francisco Examiner. 22 October 1901. p. 3.

- ^ "The Sheridan Sails". San Francisco Examiner. 17 November 1900. p. 12.

- ^ "Sheridan Carries Pesos". San Francisco Chronicle. 5 August 1909. p. 15.

- ^ "Transport Sheridan Sails". Weekly Press. 6 August 1903. p. 3.

- ^ Abridgment ... Containing the Annual Message of the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress ... with Reports of Departments and Selections from Accompanying Papers. 1907. pp. 577, 578.

- ^ "Society". San Francisco Chronicle. 11 October 1903. p. 36.

- ^ "Transport Sheridan To Sail". San Francisco Examiner. 5 November 1910. p. 23.

- ^ "Former Military Governor Tells of Present Conditions". San Francisco Examiner. 19 August 1901. p. 2.

- ^ "Going To Manila Again". San Francisco Examiner. 1 June 1901. p. 3.

- ^ "Transport Sheridan Brings Many Officers". San Francisco Call and Post. 23 December 1908. p. 7.

- ^ "30th Regiment Sails For Posts In Alaska". San Francisco Examiner. 2 June 1912. p. 61.

- ^ "Due From Manila". Fresno Morning Republican. 4 June 1902. p. 1.

- ^ "Transport Sheridan Carries Army Women To The Orient". San Francisco Call and Post. 1 September 1901. p. 15.

- ^ "Water Front News And Marine Intelligence". San Francisco Chronicle. 7 February 1911. p. 15.

- ^ "Society". San Francisco Chronicle. 11 June 1903. p. 11.

- ^ "Great Crowd Will Sail On Saturday For Manila". San Francisco Call and Post. 29 September 1904. p. 12.

- ^ "Constabulary Of Manila On Way To St. Louis". San Francisco Examiner. 16 April 1904. p. 7.

- ^ "Army Transport Sheridan Arrives". San Francisco Call and Post. 14 September 1905. p. 11.

- ^ "News From The Water Front District". San Francisco Chronicle. 26 January 1906. p. 15.

- ^ Bochkareva, Mariia Leontievna Frolkova; Levine, Isaac Don (1919). Yashka, my life as peasant, exile and soldier. Robarts - University of Toronto. London : Constable.

- ^ "Woman Death Battalion Chief, Botchkareva, Here". New York Herald. 24 May 1918. p. 16.

- ^ House, John M. (6 October 1986). Wolfhounds And Polar Bears In Siberia: America's Military Intervention 1918-1920 (PDF). University of Kansas. p. 76.

- ^ "Three Transports To Be Here In Next Few Days". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 20 December 1919. p. 2.

- ^ "Ice And Typhoon Threaten Sheridan". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. 7 February 1919. p. 8.

- ^ "1,700 Yanks, Sickened Of Siberia, Home". San Francisco Examiner. 8 December 1919. p. 11.

- ^ "U.S. Transport Sherman Ends Final Voyage". News Pilot. 7 June 1922. p. 1.

- ^ "Eight Army Transports Will Be Sold". San Francisco Examiner. 5 December 1920. p. 20.

- ^ "Bids Are Low". San Francisco Bulletin. 7 October 1922. p. 29.

- ^ "City of Honolulu Passengers, Crew Saved From Boats". San Francisco Examiner. 13 October 1922. p. 2.

- ^ "Transport Sherman For Run to Honolulu". Los Angeles Express. 16 November 1922. p. 5.

- ^ "none". Colusa Daily Sun. 19 January 1923. p. 2.

- ^ "Old U.S.S. [sic] Transport Sheridan [sic] Named Calawaii". News-Pilot. 25 December 1922. p. 8.

- ^ "Liner Made Ready For First Trip". Los Angeles Times. 1 February 1923. p. 13.

- ^ S.S. Calawaii. Los Angeles Steamship Company. 1930.

- ^ "Offshore Liners Arrive". News-Pilot. 2 April 1927. p. 8.

- ^ "Calawaii Brings Pineapple". News-Pilot. 16 November 1931. p. 7.

- ^ "17 Planes Carried to Island on Calawaii". Long Beach Sun. 18 January 1930. p. 8.

- ^ "Calawaii Here From Coast". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 17 May 1930. p. 1.

- ^ "Shipping News". Los Angeles Times. 17 January 1931. p. 7.

- ^ "Los Angeles". San Francisco Examiner. 17 February 1923. p. 20.

- ^ "Calawaii Is Back From Her Maiden Trip to Honolulu". Press Telegram. 4 March 1923. p. 36.

- ^ "Each The Finest In Its Class". Woodland Daily Democrat. 19 April 1923. p. 4.

- ^ "Stay Awhile In Enchanting Hawaii". Santa Barbara News-Press. 5 Mar 1926. p. 13.

- ^ Quinlin, Frank J. (21 October 1929). "Calawaii To Be Speeded Up". Long Beach Sun. p. 13.

- ^ "$40,000 Spent On LASSCO Ship". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 4 November 1929. p. 3.

- ^ "Pacific Liner Chartered For Ocean Picture". Los Angeles Times. 14 July 1932. p. 13.

- ^ "Matson, LASSCO In Big Merger Of Ship Holdings". Daily News. 31 October 1930. p. 14.

- ^ "Matson-LASSCO Shift Planned". Los Angeles Times. 24 June 1932. p. 15.

- ^ Drake, Waldo (26 August 1933). "Last Trip Near For Line Pair". Los Angeles Times. p. 7.

- ^ "LASSCO Crew Is Back From Japan Voyage". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 11 October 1933. p. 3.