User:HistoryofIran/Muhammad I Tapar

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:HistoryofIran/Muhammad_I_Tapar. |

| Muhammad I Tapar محمد اول تاپار | |

|---|---|

| Sultan Shahanshah | |

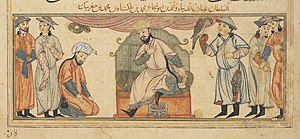

Investiture scene of Muhammad I Tapar, from the 14th-century book Jami' al-tawarikh | |

| Sultan of the Seljuk Empire | |

| Reign | 1105–1118 |

| Predecessor | Malik-Shah II |

| Successor | Mahmud II (in Iraq and western Iran) Ahmad Sanjar (in Khurasan and Transoxiana) |

| Born | 21 January 1082 |

| Died | 1118 (aged 35–36) Baghdad |

| Issue | Mahmud II Mas'ud Suleiman-Shah Tughril II Arslan |

| House | House of Seljuk |

| Father | Malik-Shah I |

| Mother | Tajuddin Safariyya Khatun |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Abu Shuja Ghiyath al-Dunya wa'l-Din Muhammad ibn Malik-Shah (Persian: ابو شجاع غیث الدنیا و الدین محمد بن مالک شاه, romanized: Abū Shujāʿ Ghiyāth al-Dunyā wa ’l-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Malik-Šāh; 1082 – 1118), better known as Muhammad I Tapar (محمد اول تاپار), was the sultan[a] of the Seljuk Empire from 1105 to 1118.

He was a son of Malik-Shah I (r. 1072–1092).

Background

[edit]Born on 21 January 1082, Muhammad was a son of the Seljuk sultan Malik-Shah I (r. 1072–1092) and a concubine named Tajuddin Safariyya Khatun.[2] He was a half-brother of Malik-Shah's eldest son Berkyaruq and a full brother of Ahmad Sanjar.[3] Muhammad was present at the death of his father in 1092 at Baghdad,[2] which marked the start of the decline and fragmentation of the empire, with amirs and palace elites trying each to gain power by supporting one of his young sons as sultan.[4][5] This would ultimately mark the start of Turkoman atabegates and principalities, which would later stretch from Kirman to Anatolia and Syria.[5]

One of Malik-Shah's wives, Terken Khatun, in cooperation with the Seljuk vizier Taj al-Mulk, installed her four-year-old son Mahmud on the throne at Baghdad.[6] She convinced the Abbasid caliph al-Mustazhir (r. 1094–1118) to have the khutba (friday sermon) read in Mahmud's name, and sent an army under the amir Qiwam al-Dawla Kirbuqa to take Isfahan and capture Berkyaruq.[4] Meanwhile, the family and supporters of the deceased Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk (known as the "Nizamiyya"), led by the Turkic slave-soldier (ghulam) Er-Ghush, supported Berkyaruq. They had Berkyaruq smuggled out of Isfahan and sent to his atabeg (guardian) Gumushtigin in Saveh and Aveh, who had him crowned at Ray.[7][6]

After a while, Muhammad was taken to Isfahan by his stepmother Terken Khatun, who was soon besieged by Berkyaruq. During the siege, Muhammad managed to escape to his mother, who was with Berkyaruq.[2] Terken Khatun soon abruptly died in 1094, with her sickly son Mahmud dying a month later.[4][8]

Conflict with Berkyaruq

[edit]

The most difficult challenge that Berkyaruq faced was the rebellion of his half-brother Muhammad in 1098 or 1089. The rebellion had been encouraged by Nizam al-Mulk's son Mu'ayyid al-Mulk, who had formerly served Berkyaruq and played a key-role in the defeat of Tutush. After his dismissal by Berkyaruq, he entered into the service of Muhammad, who appointed him as his vizier. Mu'ayyid al-Mulk made use of his newfound position to exact vengeance on his rivals, which was made easier because Muhammad had yet to reach adulthood (approximately 17 years old at the time). The Nizamiyya and the prominent families of Isfahan also joined Muhammad, stopping Berkyaruq from entering the city.[9] The rebellion was launched from Muhammad's base at the city of Ganja in Arran, which had been given to him as an iqta' (land grant) by Berkyaruq back in 1093.[10]

Muhammad's capture of Ray exposed the vulnerability of Berkyaruq's realm. Sa'd al-Dawla Gawhara'in, the shihna (military administrator) of Baghdad, soon joined Muhammad, which implies that the city was also added to his domain. Nevertheless, the five-year war continued to be indecisive, with Baghdad repeatedly changing hands. Even with the support of Sanjar (who despised Berkyaruq), Muhammad was unable to defeat his rival. Berkyaruq's authority continued to weaken, and by 1104, with his treasury exhausted, he was forced to sue for peace.[11] A treaty was subsequently made, which acknowledged Muhammad as the ruler of southern Iraq, northern Iran, the Diyar Bakr, Mosul and Syria, while Berkyaruq was acknowledged as the ruler of the rest of Iran (including Isfahan) and Baghdad. The treaty, however, did most likely not display the true circumstances of the situation. The following year (1105), there were no coin mints citing the name of Berkyaruq in the central Islamic lands.[12] En route to Isfahan, he died of tuberculosis at the age of 25 near the town of Borujerd, and was succeeded by his infant son Malik-Shah II.[13] Baghdad was subsequently captured by Muhammad, who had Malik-Shah II killed.[12]

Reign

[edit]Legacy and assessment

[edit]Muhammad was the last Seljuk ruler have a strong authority in the western part of the sultanate.[14] The Seljuk realm was in a dire state after Muhammad's death, according to bureaucrat and writer Anushirvan ibn Khalid (died 1137/1139); "In Muhammad's reign the kingdom was united and secure from all envious attacks; but when it passed to his son Mahmud, they split up that unity and destroyed its cohesion. They claimed a share with him in the power and left him only a bare subsistence."[14] Muhammad is mainly portrayed in a positive light by contemporary historians. According to the historian Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani (died 1201), Muhammad was "the perfect man of the Seljuk dynasty and their strongest steed."[15]

Muhammad's ceaseless battles and wars inspired one of his poets Iranshah to compose the Persian epic poem of Bahman-nama, an Iranian mythological story about the ceaseless battles between Kay Bahman and Rostam's family. This implies that the work was also written to serve as advice for solving the socio-political issues of the time.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In addition to sultan, the ancient Persian title of King of Kings (shahanshah) was also used by the Seljuks.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ Madelung, Daftary & Meri 2003, p. 330.

- ^ a b c Özaydın 2005, p. 579.

- ^ Bosworth 1993, p. 408.

- ^ a b c Peacock 2015, p. 76.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1988, pp. 800–801.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1968, p. 103.

- ^ Tetley 2008, p. 105.

- ^ Bosworth 1968, p. 105.

- ^ Peacock 2015, p. 78.

- ^ Tetley 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Peacock 2015, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Peacock 2015, pp. 80, 133.

- ^ Özaydın 1992, p. 516.

- ^ a b Bosworth 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Peacock 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Askari 2016, p. 33.

Sources

[edit]- Askari, Nasrin (2016). The medieval reception of the Shāhnāma as a mirror for princes. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-30790-2.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1968). "The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217)". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Saljuq and Mongol periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–202. ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1988). "Barkīāroq". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume III/8: Bardesanes–Bayhaqī, Ẓahīr-al-Dīn. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 800–801. ISBN 978-0-71009-120-8.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1993). "Muḥammad b. Malik-S̲h̲āh". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 408. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Bosworth, C.E. (2001). "Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Faḍl Bayhaqī's Tārīkh-i Masʿūdī". Oriens. 36. Brill: 299–313. doi:10.2307/1580488. JSTOR 1580488.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2010). "The steppe peoples in the Islamic world". In Morgan, David O.; Reid, Anthony (eds.). The New Cambridge History of Islam (Volume 3). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–78. ISBN 978-0521850315.

- Cahen, Cl (1960). "Barkyārūḳ". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469456.

- Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad; Meri, Josef W. (2003). Culture and Memory in Medieval Islam: Essays in Honor of Wilferd Madelung. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-859-5.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (1992). "Berkyaruk". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 5 (Balaban – Beşi̇r Ağa) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. ISBN 978-975-389-432-6.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2005). "Muhammmed Tapar". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 30 (Misra – Muhammedi̇yye) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 579–581. ISBN 978-975-389-402-9.

- Peacock, A. C. S. (2015). The Great Seljuk Empire. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–378. ISBN 978-0-7486-3826-0.

- Richards, D.S. (2014). The Annals of the Saljuq Turks: Selections from al-Kamil fi'l-Ta'rikh of Ibn al-Athir. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-83254-6.

- Tetley, Gillies (2008). The Ghaznavid and Seljuk Turks: Poetry as a Source for Iranian History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-08438-8.

- Van Donzel, Emeri Johannes (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09738-4.