User:Elenica aa/sandbox

El Greco's View of Toledo

[edit]Official church and Mystic City

[edit]The church was an essential part in the life of all Toledo’s citizens. Archbishop of Toledo was powerful figure and held an important position and Spain’s clerical hierarchy. During the Reformation period, Gaspar de Quiroga, archbishop of Toledo from 1577-1594, enforced ordinances of Council of Trent in every possible way (53).[1] Quiroga strictly followed new standards of Counter-Reformation and initiated many reforms in the church of Toledo. Decree of 1601 prohibited the profane paintings to be placed in the church, and the archdiocesan council was established to regulate religious art (58).[1] The council invited leading artist to select appropriate works of art. Interestingly, El Greco and his son Jorge Manuel were members of this establishment (58).[1]

Despite the attempts of the official church to follow the precepts of Council of Trent, mystics and spiritual writers were very popular in Spain of the 2nd half of XVI, especially in Toledo. The most known and revered mystics were Saint Theresa and Saint John of the Cross. Both were advocates of personal devotion to Christ and honored direct experience of connection with the divine. Practises of asceticism, praying in the wilderness, meditation, emphasise on the Christ the Redeemer were highly admired among the mystics. Many spiritual writers draw their inspiration from the books of Erasmus, Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite, Plato and Plotinus. Thus Plotinus’ idea of possibility to glimpse on the higher realms via ecstasies corresponded to the spiritual insights of mystics. It is certainly that El Greco was familiar with treatises of spiritual writers and perhaps shared some of their views (book by Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite was found in the artist’s library) (63).[2] El Greco personally knew supporters of mystics, for example, his patron Diego De Castilla was an admirer of Saint Theresa. Also some of El Greco’s acquaintances were conversos, many of whom shared sympathy for the mystic’s concept of “New Man” (62).[2] The atmosphere of mystic Toledo could leave the imprint on El Greco’s artistic development, as David Davis put it, “An examination of the style of El Greco’s paintings reveals that he creates a pictorial language that expresses the ideology of the spiritual reformers” (68).[2] Though El Greco was familiar with important spiritual writings and was a friend with proponents of such ideas, unfortunately, it is unknown whether El Greco supported mystics himself, was one them, or simply was trying to recreate the ecstatic experience on the canvas.

Painting

[edit]

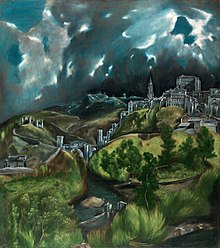

One of the El Greco’s well-known painting is dedicated to the city of Toledo, where artist lived and worked in the most time of his life. El Greco rarely painted landscapes which make View of Toledo especially unique artwork. The artist depicts the city of Toledo surrounded by the vast land. The architectural elements such as alcazar, cathedral, the Alcantara Bridge, and the Castle of San Servando match the actual typographical landmarks (19).[3]

El Greco’s depiction of the view is rather distorted. It becomes obvious if one compares View of Toledo with the photograph taken from the same vantage point. Thus the painted hill is more tall and narrow, the Tagus river depicted in the middle of the painting is more visible to the viewer that if it was observed from the exactly the same point in the reality. Another comparison can be made with drawing of Toledo by Flemish artist Anton van der Wyngaerde. Unlike Wyngaerde, who includes every visible feature of land and cityscape without altering the view, El Greco’s version is quite abbreviated: two-third of the city is eliminated and only key landmarks are retained (26).[3]

Emblematic View

[edit]

El Greco’s choice to depict his city in such a peculiar way can be referred to the Middle Ages artistic tradition of emblematic view. Drawings of emblematic views often portrayed land or city with the emphasise on the important topographical features. One of the most famous drawing of this genre is View of Venice by Jacopo de Barbari and most likely El Greco saw this work in print. However, El Greco’s modification of and deviation from the conventional depiction of emblematic views can be explained as a subjective expression of the artist. El Greco offers his own interpretation of the tradition and uses it as an effective mean to show wealth, power and beauty of Toledo (28).[3]

Details

[edit]View of Toledo contains few curious details. The true meaning of these features a still unknown, however, they can be read as a symbol. One of the detail is the unidentified structure in front of alcazar. Similar buildings were used an aristocratic palaces and perhaps El Greco used it as a symbol of Toledo’s prestigious families that were essential for city’s prosperity and reputation (26).[3] Another questionable element is a group of the buildings on the left. These buildings are situated on the different kind of ground that other buildings on the painting. Some scholars speculate that this unusual ground is indeed a cloud, which was used by El Greco as a device to draw attention to the important sites (26).[3] This structure could be the Agaliense monastery, where Saint Ildefonsus, the patron city of Toledo, went on retreat. Therefore, inclusion of such symbolic reference signifies artist’s intention to pay an homage to the important saint (26).[3]

El Greco uses the landscape from View of Toledo in two other paintings: Saint Joseph and the Christ Child and Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. Religious context of both canvases makes Toledo an active participant in the spiritual scene. El Greco adds almost identical land from View of Toledo in the background for Saint Joseph and the Christ Child. The latter was installed to the altarpiece of the Capilla of San Jose with the inscription naming Christ Child the Ruler of Toledo (28).[3] Background of Virgin of the Immaculate Conception too has the elements from View of Toledo, in this reference Toledo becomes analogous to the City of God (26).[3]

- ^ a b c Kagan, Richard (1982). Bourdain, Anthony (ed.). "The Toledo of El Greco". El Greco of Toledo. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- ^ a b c Davies, David (1984). "El Greco and the Spiritual Reform Movements in Spain". Studies in the History of Art. 13: 57–75 – via JSTORE.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown, Jonathan; Kagan, Richard. "View of Toledo". Studies in the History of Art. 11: 19–30.