User:De Insomniis/Drafts/Michael A. Aquino

Lieutenant Colonel Michael A. Aquino Ph.D. | |

|---|---|

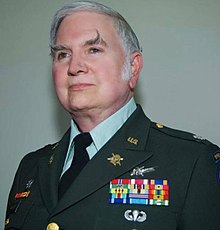

Lieutenant Colonel Aquino in military uniform | |

| Title | Ipsissimus |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Michael Angelo Aquino, Jr. October 16, 1946 |

| Died | November 1, 2019 (aged 73) |

| Cause of death | unknown |

| Nationality | American |

| Home town | San Francisco, California |

| Spouse | Lilith Sinclair |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | University of California Santa Barbara |

| Known for | Military officer, Author, Founder of the Temple of Set |

| Other names | Ra-En-Set |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Temple of Set |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Temple of Set |

| Post | Ipsissimus (6th degree) |

| Period in office |

|

| Successor | James Fitzsimmons (2013) |

| Military service | |

| Rank | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Service years | 1968–2006 |

| Unit | |

| Conflict | Vietnam War |

| Awards | List of awards

|

| Website | xeper |

Dr. Michael A. Aquino (born October 16, 1946) Baron of Rachane, FSA Scot, is a retired American Army officer, academic and occultist.[1] Aquino was a career officer with the US army specializing in psychological warfare, serving in the Vietnam War where he came to the rank of Lieutenant colonel.

When he returned from Vietnam the army stationed him in Kentucky and there he became a priest within the Church of Satan, but eventually became disenchanted with the leadership of Anton LaVey, and in 1975 he split from the Church of Satan and established a church of his own known as the Temple of Set.

Background

[edit]Michael Aquino was born to affluent parents in San Francisco, California. He attended high school Santa Barbara and graduated from the University of California Santa Barbara in 1968 with a B.A. in political science. Following his deployment in Vietnam he earned his M.A. in 1976, and in 1980 Aquino was awarded a Ph.D. in political science.

He served in the United States Army from February 23, 1962, to March 1, 1963, and earned the rank of lieutenant colonel. As a young officer, Aquino served two years in Vietnam, rising from platoon leader to troop commander.[2] In 1980 Aquino, then Major serving as Research and Analysis team leader at 7th PSYOP Group in San Francisco with then-PSYOP analyst Paul E. Vallely co-authored a paper concerning the use of psychological operations entitled From PSYOP to MindWar: The Psychology of Victory[3] which focused on the application of the 4th generation of warfare to an enemy population.

From 1980 to 1986 Aquino worked as an adjunct professor of political science at Golden Gate University. The various scandals surrounding him and his career became too much of a burden and in the 2000s he retired from public life and turned over the operations of the Temple of Set to Don Webb, and he lived in semi-retirement until his death in 2019. Aquino's cause of death is unknown, though the obituary published on the Temple of Set website[4] notes that he had been "experiencing declining health for several years".

Religion

[edit]LaVeyan Satanism

[edit]In 1970, while he was serving with the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, Aquino was stationed in Bến Cát in South Vietnam when he wrote a tract titled "Diabolicon" in which he reflected upon his growing divergence from the Church of Satan's doctrines.[5] In this tract, teachings about the creation of the world, God, and humanity are presented, as is the dualistic idea that Satan complements God.[6] The character of Lucifer is presented as bringing insight to human society,[7] a depiction of Lucifer that was inherited from John Milton's seventeenth-century epic poem Paradise Lost.[8]

By 1971 Aquino was ranked as a Magister Caverns of the IV° within the Church's hierarchy, was editor of its publication The Cloven Hoof, and sat on its governing Council of Nine.[9] In 1973 he rose to the previously unattained rank of Magister Templi of IV°.[9] According to the scholars of Satanism Per Faxneld and Jesper Petersen, Aquino had become LaVey's "right-hand man".[10] There were nonetheless things that Aquino disliked about the Church of Satan; he thought that it had attracted many "fad-followers, egomaniacs, and assorted oddballs, whose primary interest in becoming Satanists was to flash their membership cards for cocktail-party notoriety".[11] When, in 1975, LaVey abolished the system of regional groups, or grottos, and declared that in the future all degrees would be given in exchange for financial or other contributions to the Church, Aquino became increasingly disaffected; he resigned from the organization on June 10, 1975.[12] While LaVey seems to have held a pragmatic and practical view of the degrees and of the Satanic priesthood, intending them to reflect the social role of the degree holder within the organization, Aquino and his supporters viewed the priesthood as being spiritual, sacred and irrevocable.[13] Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen describe Aquino as, in effect, accusing LaVey of the sacrilege of simony.[13]

Setian Religion

[edit]Foundation of the Temple of Set

[edit]Aquino then provided what has been described as a "foundation myth" for his Setian religion.[14] Having departed the Church, he embarked on a ritual intent on asking Satan for advice on what to do next.[15] According to his account, at Midsummer 1975, Satan appeared and revealed that he wanted to be known by his true name, Set, which had been the name used by his worshippers in ancient Egypt.[16] Aquino produced a religious text, The Book of Coming Forth by Night, which he alleged had been revealed to him by Set through a process of automatic writing.[17] According to Aquino, "there was nothing overtly sensational, supernatural, or melodramatic about The Book of Coming Forth By Night working. I simply sat down and wrote it."[18] The book proclaimed Aquino to be the Magus of the new Aeon of Set and the heir to LaVey's "infernal mandate".[19] Aquino later stated that the revelation that Satan was Set necessitated his own exploration of Egyptology, a subject about which he had previously known comparatively little.[20]

Aquino's Book of Coming Forth by Night makes reference to The Book of the Law, a similarly 'revealed' text produced by the occultist Aleister Crowley in 1904 which provided the basis for Crowley's religion of Thelema. In Aquino's book, The Book of the Law was presented as a genuine spiritual text given to Crowley by preternatural sources, but it was also declared that Crowley had misunderstood both its origin and message.[21] In making reference to The Book of the Law, Aquino presented himself as being as much Crowley's heir as LaVey's,[22] and Aquino's work would engage with Crowley's writings and beliefs to a far greater extent than LaVey ever did.[23]

In establishing the Temple, Aquino was joined by other ex-members of LaVey's Church,[9] and soon Setian groups, or pylons, were established in various parts of the United States.[9] The structure of the Temple was based largely on those of the ceremonial magical orders of the late nineteenth century, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and Ordo Templi Orientis.[24] Aquino has stated that he believed LaVey not to be merely a charismatic leader but to have been actually appointed by Satan himself (referring to this charismatic authority as the "Infernal Mandate") to found the Church.[25] After the split of 1975, Aquino believed LaVey had lost the mandate, which the "Prince of Darkness" then transferred to Aquino and a new organization, the Temple of Set.[25] According to both the historian of religion Mattias Gardell and journalist Gavin Baddeley, Aquino displayed an "obsession" with LaVey after his departure from the Church, for instance by publicly releasing court documents that reflected negatively on his former mentor, among them restraining orders, divorce proceedings, and a bankruptcy filing.[26] In turn, LaVey lampooned the new Temple as "Laurel and Hardy's Sons of the Desert".[27] In 1975, the Temple incorporated as a non-profit Church in California, receiving state and federal recognition and tax-exemption later that year.[28]

Controversies

[edit]He has been implicated in the Presidio child abuse case of the 1980s[29][30][31][32] and the Franklin scandal; accusations that he fervently denied throughout the rest of his life, framing the day-care child abuse cases of the 80s as "witch hunts".[33][34] At the height of the "Satanic Panic" Aquino became the preeminent spokesperson for modern-day satanism, and made several controversial appearances on daytime talkshows such as Oprah! and The Arsenio Hall Show.

No charges were ultimately laid against Aquino by the U.S. Army, and the SFPD discontinued their investigation into Michael and Lilith Aquino (in regard to the Presidio case) in 1988. In 1991 Aquino filed a suit against United States Secretary of the Army Michael P.W. Stone to compel the army to amend the investigative report in order to strike both his and his wife's names from the record. While the United States Army Criminal Investigation Command deleted Mrs. Aquino's name entirely, on the ground that the identifications of her by the children interviewed were inadequate, it did not delete LTC Aquino's name, and all the child-abuse charges remained, because "the evidence of alibi offered by LTC Aquino [was] not persuasive."[35]

References

[edit]- ^ "Interview with Lt Colonel Michael Aquino — Satanist & Psychological Warfare Specialist » The Event Chronicle". web.archive.org. 16 September 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Lt. Colonel Dr. Michael A. Aquino, Ph.D. – April 16th 2015 – Dr. J Radio Live". web.archive.org. 20 September 2017.

- ^ ""Major Michael A. Aquino, Ph.D. and Paul Valley: Mind War – 1980"". web.archive.org. 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Michael A. Aquino". xeper.org.

- ^ Schipper 2010, p. 112; Introvigne 2016, p. 317.

- ^ Schipper 2010, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Schipper 2010, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Schipper 2010, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Gardell 2003, p. 290.

- ^ Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Drury 2003, p. 193.

- ^ Gardell 2003, p. 290; Drury 2003, pp. 193–194; Baddeley 2010, p. 102; Granholm 2013, p. 217.

- ^ a b Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Schipper 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Drury 2003, p. 194; Baddeley 2010, p. 103; Dyrendal 2012, p. 380; Granholm 2013, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Gardell 2003, p. 290; Drury 2003, p. 194; Schipper 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Medway 2001, p. 22; Gardell 2003, p. 290; Drury 2003, p. 194; Baddeley 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Dyrendal 2012, p. 381.

- ^ Dyrendal 2012, p. 380.

- ^ Drury 2003, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Dyrendal 2012, p. 381; Petersen 2012, p. 99.

- ^ Dyrendal 2012, p. 380; Petersen 2012, p. 99.

- ^ Dyrendal 2012, p. 379.

- ^ Petersen 2005, p. 435; Baddeley 2010, p. 103.

- ^ a b Asprem 2012, p. 118.

- ^ Gardell 2003, p. 390; Baddeley 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Baddeley 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Harvey 1995, p. 285.

- ^ Aquino, Michael (June 13 2014). Extreme Prejudice: The Presidio "Satanic Abuse" Scam. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 1500159247.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ https://apnews.com/b6377fb5aceb98a9b0fe99ab978213cc saved at Archive.org

- ^ https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-08-11-mn-846-story.html saved at Archive.org

- ^ https://educate-yourself.org/cn/The-Pedophocracy-Part-III-Dave-McGowan-aug2001.shtml

- ^ https://konformist.com/2001/aquino.htm saved at Archive.org

- ^ https://xeper.org/maquino/nm/PSFSummary.pdf saved at Archive.org

- ^ "Aquino v. Stone, 957 F.2d 139 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com.