User:DalomirDreanor/sandbox

Tetramorph

[edit]

In Christian symbolism, the tetramorphs were the symbol of the four Evangelists or their symbolic creatures, the Four Living Creatures. Each of the four Evangelists corresponds to a symbolic creature: St Matthew as the winged man, St Mark as the lion, St Luke as the ox, and St John as the eagle. In Christian art and iconography, the Evangelists are often represented as tetramorphs. Evangelist portraits that depict them in their human forms are often accompanied by their symbolic creatures. The creatures that represent each of the Evangelists are first described in the book of Ezekiel, and again later in the Revelation of John.

Origins

[edit]Images of tetramorphs, unions of different elements into one symbol, were originally used by the Ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, and Greeks. The image of the sphinx, found in Egypt and Babylon, depicted the body of a lion and the head of a human, while the harpies of Greek mythology showed bird-like human women. The Egyptians and Assyrians in particular were the first to attach wings to their divine images (insert citation). The tetramorphs of the Evangelists can be traced back to the winged animals of Assyrians art and sculpture. Ezekiel’s vision, from which the images of the tetramorphs are derived, are believed to have been influenced by the ancient art of Assyria [1].

The animals associated with the tetramorphs of the Evangelists originate from the Babylonian symbols of the four fixed signs of the zodiac: the ox, representing Taurus; the lion, representing Leo; the eagle, representing Scorpio; the man, representing Aquarius [2]. The four symbols also represented the four pagan elements earth, air, fire, and water. These animals were also common in Egyptian, Greek, and Assyrian mythology. The early Christians adopted this symbolism and adapted it for the four Evangelists [3] as the tetramorphs, which first appear in Christian art in the 5th century [4].

The images of the tetramorphs in Christian theology first appear in the vision of Ezekiel, who describes the four creatures as they appear to him in his book:

- As for the likeness of their faces, they four had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and they four had the face of an ox on the left side; they four also had the face of an eagle. [5]

They are described later in the Apocalypse of the Revelation of John: ”And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast like a calf, and the third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle.” [6]

Though there are several inconsistencies between the records of St Augustine, Irenaeus, and St Jerome, St Jerome is generally credited with assigning the tetramorphs to each of the Evangelists. The tetramorphs, just as the four gospels of the Evangelists, represent four facets of Christ.

- Matthew the Evangelist is represented as the winged man, or an angel. He is represented in human form because his gospel centres on the human nature and life of Christ. St Jerome writes, ”The first face of a man signifies Matthew, who began his narrative as though about a man: ‘The book of the generation of Jesus Chris the son of David, the son of Abraham’” [7].

- Mark the Evangelist is represented as a lion. He is represented in the form of a lion because he proclaims the royal dignity of Christ, the lion being the king of beasts. ”The second [face signifies] Mark in whom the voice of a lion roaring in the wilderness is heard: 'A voice of one shouting in the desert: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.'”

- Luke the Evangelist is represented as an ox, or a calf. He is represented in the form of an ox as his gospel dwells on the atonement and the sacrifice of Christ, the ox being an ancient symbol of sacrifice. ”The third [is the face] of the calf which prefigures that the evangelist Like began with Zachariah the priest.”

- John the Evangelist is represented as an eagle. He is represented as an eagle as his gospel describes Christ’s Ascension and the incarnation of the divine Logos, the eagle itself a symbol of ascension and flight. ”The fourth [face signifies] John the evangelist who, having taken up eagle’s wings and hastening toward higher matters, discusses the Word of God.”

Tetramorphs in Art

[edit]Representation and Symbolism

[edit]

The tetramorphs as they appear in their animal forms are predominantly shown as winged figures. The wings, an ancient symbol of divinity, represent the divinity of the Evangelists, the divine nature of Christ, and the virtues required for Christian salvation .[8] In regards to the depiction of St Mark in particular, the use of wings distinguish him from images of St Jerome, who is also associated with the image of a lion [9].

The perfect human body of Christ was originally represented as a winged man, and was later adapted for St Matthew in order to symbolise Christ’s humanity[10]. In the context of the tetramorphs, the winged man indicates Christ’s humanity and reason, as well as Matthew’s account of the Incarnation of Christ[11]. The lion of St Mark represents courage, resurrection, and royalty, coinciding with the theme of Christ as king in Mark’s gospel. It is also interpreted as the Lion of Judah as a reference to Christ’s royal lineage[12]. The ox, or bull, is an ancient Christian symbol of redemption and life through sacrifice[13], signifying Luke’s records of Christ as a priest and his ultimate sacrifice. The eagle represents the sky, heavens, and the human spirit, paralleling the divine nature of Christ[14].

In their earliest appearances, the Evangelists were depicted in their human forms each with a scroll or a book to represent the Gospels. By the 5th century, images of the Evangelists evolved into their respective tetramorphs [15]. By the later middle ages, the tetramorphs were used less frequently and the Evangelists were often shown in their human forms accompanied by their symbolic creatures, or as human men with the heads of animals [16].

In images where the creatures surround Christ, the winged man and the eagle are often depicted at Christ’s sides, with the lion and the ox positioned lower by his feet, with the man on Christ's right, taking precedence over the eagle, and the lion to the left of the ox. This positions reflects the medieval great chain of being[17].

Depictions in Christian Art

[edit]Architecture

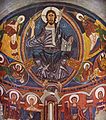

[edit]The use of the tetramorphs in architecture is most common in the decoration of Christian churches. On medieval churches, the symbols of the Evangelists are usually found above westerly-facing portals and in the eastern apse, particularly surrounding the enthroned figure of Christ in Glory in scenes of the Last Judgment[18]. This image of Christ in Glory often features Christ pantocrator in a mandorla surrounded by the tetramorphs is often found on the spherical ceiling inside the apse, typically as a mosaic or fresco. Older Roman churches, such as Santa Pudenziana and Santa Maria in Trastevere, mosaics often depict the four creatures in a straight line rather than in a circular formation[19].

Medieval churches also feature sculptures of bas-relief symbols of the Evangelists on western facades, externally around eastern apse windows, or as large statues atop apse walls[20]. Generally all four tetramorphs will be found together in either one image or in one structure, but it is not unheard of to have a single Evangelist dominate the imagery of the church. This is usually found in cities that bear one of the Evangelists as their patron saint. A notable example is St Mark's Basilica in Venice, where the winged lion is the city's mascot and St Mark is the city's patron saint.

-

12th century apsis mosaic from Basilica di San Clemente in Rome.

-

Deatil of the rooftop of San Marco cathedral in Venice.

-

Central portal of Chartres Cathedral in Chartres.

Painting and Manuscript Illumination

[edit]In most illuminated texts, the Gospels were often prefaced with a portrait of the respective Evangelist. Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts were very focused on abstract linear patterns that were adopted from Anglo-Saxon and Celtic metalwork. The Celts and Hiberno-Saxons used a lot of animalistic imagery in their illumination, focusing more on images of animals than humans. As a result, in early Gospel Books the Evangelists were represented as tetramorphic symbols rather than portraits. Their preferences for abstract, geometric, and stylized art led to a lot of differences in portrayals of the tetramorphs. Celtic artists would paint the creatures in a relatively realistic fashion, or their divine nature would be emphasised through the inclusion of wings or human traits, such as hands in place of talons or the animal standing upright[21].

The Evangelists and tetramorphs were highly featured in Ottonian manuscripts as the Gospel books, periscopes, and the Apocalypse were most popular and while they imitated the Byzantine artistic style, Carolingian illuminations consciously revived the early Christian style, and was much more elaborate than Celtic or Insular art.

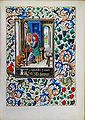

For most illuminated manuscript portraits, the Evangelist typically occupied a full page. Though numerous examples of Late Antique portraits featured each figure in a standing position, the Evangelists were predominantly depicted in a seating position at a writing desk or with a book or scroll, both in reference to the Gospels. The symbols of the tetramorphs were most common in the middle ages through to the Romanesque period before they fell out of favour and images of the Evangelists in their human forms became more common. However, the tetramorphs were used still used and were found in artwork of the Renaissance and even in modern art.

-

St Mark as the lion as depicted in the Echternach Gospels, c. 800, Hiberno-Saxon.

-

Illumination of the four Evangelists with their symbols, c. 820, Carolingian.

-

Christ and the tetramorphs in the Bamberg Apocalypse, c. 1000, Ottonian.

Gallery

[edit]-

The tetramorphs as illustrated in the Book of Kells, c. 800, Celtic manuscript illumination.

-

Christ surrounded by the Evangelists, c. 1123, Romanesque fresco.

-

Christ in Majesty from the Aberdeen Bestiary, c. 12th century, manuscript illumination.

-

St Luke in The Hours of Mary of Burgundy, c. 1477, Northern Renaissance manuscript illumination.

-

Vision of Ezekiel by Raphael, c. 1518, Renaissance painting.

-

St John the Evangelist by Domenichino, c. 1621-9, Renaissance painting.

-

Statue of St John outside Saint John's Seminary in Boston, c. 1884.

-

Christ in Glory by Graham Sutherland, c. 1962, tapestry.

References

[edit]- ^ Whittick, Arnold. Symbols, Signs, and their Meaning. Leonard Hill Ltd, 1960, p. 134.

- ^ ”Four Evangelists (Tetramorphs)”. Symboldictionary. http://symboldictionary.net/?p=486

- ^ ”Four Evangelists (Tetramorphs)”. Symboldictionary. http://symboldictionary.net/?p=486

- ^ Clement, Clara Erskine. Saints in Art. Gale Research Company, 1974, p. 34.

- ^ Ezekiel 1:10.

- ^ Revelation 4:7.

- ^ Saint Jerome. Commentary on Matthew. p. 5.

- ^ Male, Emile. The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century. HarperCollins, 1913, pp. 35-7.

- ^ Clement, Clara Erskine. Saints in Art. Gale Research Company, 1974, p. 48.

- ^ Charbonneau-Lassay, Louis. The Symbolic Animals of Christianity. Stuart & Watkins, 1970.

- ^ Schuetz-Miller, Mardith K. “Survival of Early Christian Symbolism in Monastic Churches of New Spain and Visions of the Millennial Kingdom”. Journal of the Southwest. 42.4 (2000): 763-800. Print.

- ^ Schuetz-Miller, Mardith K. “Survival of Early Christian Symbolism in Monastic Churches of New Spain and Visions of the Millennial Kingdom”. Journal of the Southwest. 42.4 (2000): 763-800. Print.

- ^ Charbonneau-Lassay, Louis. The Symbolic Animals of Christianity. Stuart & Watkins, 1970.

- ^ ”Symbols of the Four Evangelists in Christian Art”. Sacred Destinations. http://www.sacred-destinations.com/reference/symbols-of-four-evangelists.

- ^ Clement, Clara Erskine. Saints in Art. Gale Research Company, 1974, p. 34.

- ^ Tabon, Margaret. The Saints in Art. Gale Research Company, 1969, p. 72.

- ^ ”Symbols of the Four Evangelists”. Sacred Destinations. http://www.sacred-destinations.com/reference/symbols-of-four-evangelists.

- ^ "Symbols of the Four Evangelists". Sacred Destinations. http://www.sacred-destinations.com/reference/symbols-of-four-evangelists.

- ^ "Archangels and Evangelists". Paradox Palace. http://www.paradoxplace.com/Church_Stuff/Archangels_Evangelists.htm.

- ^ "Archangels and Evangelists". Paradox Palace. http://www.paradoxplace.com/Church_Stuff/Archangels_Evangelists.htm.

- ^ ”Irish Illuminated Manuscripts”. Visual Arts Cork. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/cultural-history-of-ireland/illuminated-manuscripts.htm.