User:Colin Douglas Howell/Galleries/Steam locomotives of the Rainhill Trials

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first railway to use steam locomotives to carry passenger traffic. In October 1829, as the new railway was nearing completion, it held a competition known as the Rainhill Trials to judge the performance of locomotive designs. The winner (and indeed the only locomotive to complete the trials) was Robert Stephenson's Rocket. Its revolutionary design became the foundation for almost all steam locomotives that followed.

These are the steam locomotives which participated in the trials.

Hackworth's Sans Pareil

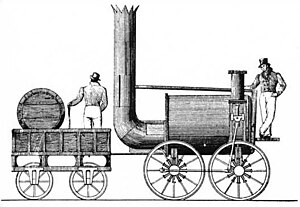

[edit]The most conventional of the locomotives at the Rainhill Trials was Timothy Hackworth's Sans Pareil, which was similar to previous Hackworth designs such as Royal George. It ran cylinders-first, with the driver at the front; the firebox and smokestack were both at the rear. Although it was slightly too heavy for the trials' weight limits on four-wheel locomotives, and it was unable to finish due to a water pump failure that caused the boiler's fusible plug to melt, it still proved to be quite an effective locomotive after being repaired. (However, its vertical cylinders and lack of springing would have caused excessive rocking and "hammerblow" at high speeds.) The Liverpool and Manchester bought it and leased it to the Bolton and Leigh Railway, where it operated until 1844. It spent another two decades as a stationary engine before being retired and restored for preservation. It now resides at the Shildon Locomotion Museum. A working replica was built in 1980; this is also kept at Shildon.

-

Contemporary engraving of Sans Pareil

-

Sans Pareil on display at Shildon.

-

The Sans Pareil replica at a demonstration at Manchester. (More photos.)

Timothy Burstall's Perseverance

[edit]Perseverance, built by Timothy Burstall, was the least successful of the steam locomotives to run at Rainhill. It was damaged on the way to the trials, required several days for repairs, and in the end could only manage 6 mph without a load. The rules for the trials required an average speed of 10 mph with a load of three times the locomotive's weight.

-

An 1829 engraving of Perseverance.

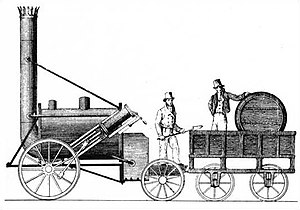

Novelty was built by the engineers John Ericsson and John Braithwaite. They had only heard about the Rainhill contest several weeks before, so Novelty was developed in a hurry. It may have used some design elements of the steam fire engines that Ericsson and Braithwaite had been building. It was certainly the most innovative and unconventional locomotive at Rainhill. Its boiler was hammer-shaped, with a vertical firebox at the engine's front and a horizontal extension running beneath the operators' platform all the way to the thin smokestack at the rear. A mechanical blower provided forced draft for the boiler. The vertical cylinders were at the rear and drove horizontal bell cranks connected to the front crank axle, the first such axle to be used on a locomotive. Since Novelty carried its water and coal on board, it was also effectively the first tank engine. Novelty reached speeds of 28 mph during the trials, but it suffered a series of mechanical failures that forced it to withdraw.

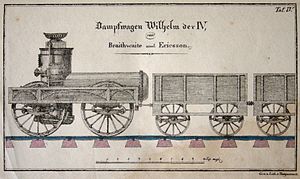

Although a number of Novelty's design features proved to be impractical, Ericsson and Braithwaite built two larger engines of the same basic design, William IV and Queen Adelaide. These, along with Novelty, were operated for a few years by the St Helens and Runcorn Gap Railway, which crossed the Liverpool and Manchester.

A working replica of Novelty was reconstructed in 1980.

(John Ericsson had a long career as an inventor; the U.S. Civil War ironclad USS Monitor was his creation.)

-

An 1829 engraving of Novelty.

-

The working replica of Novelty during a visit to Manchester. (More photos.)

-

An 1833 engraving of the Novelty-type locomotive William IV.

The famous Rocket was mostly designed by Robert Stephenson, with some input from his father George. Some of its features, such as direct drive of the wheels and inclined cylinders, had been introduced on earlier engines like Royal George and Lancashire Witch. Rocket’s use of a fire-tube boiler together with a blastpipe for draft was a new development, and this combination was key to the locomotive's success, allowing its boiler to generate much more power than the flued boilers then in common use. Its single pair of driving wheels was also a new feature, introducing the 0-2-2 wheel configuration that Stephenson would use for a number of successor engines. (Novelty also had this configuration.) Rocket was a light locomotive, designed for pulling light passenger trains at higher speeds, so it did not need the greater traction provided by two driven axles. Thus the second pair of wheels could be made smaller and lighter to save weight. Rocket was the only locomotive to successfully finish the Rainhill Trials, and thus it won the competition. Afterward it became one of the first locomotives to serve on the Liverpool and Manchester. During this period it was greatly modified: its firebox was enlarged, it was fitted with a proper smokebox, and its cylinders were lowered to a nearly horizontal position, reducing the rocking motion that a steeply inclined cylinder configuration was still prone to.

Rocket has been preserved at the National Railway Museum in its later, altered form. The museum also has two replicas, one a cutaway replica, the other a fully working replica. These replicas have the original form used at Rainhill. (Some photos of the working replica show it with a shortened smokestack which allows it to pass under bridges built for modern clearance standards.)

-

An 1829 engraving of Rocket.

-

The working replica of Rocket on tour at the Beamish Museum. (More replica photos.)

-

Rocket on display at the National Railway Museum, showing its post-Rainhill configuration. The connecting rods have been removed. (More photos.)