User:CactusJack/USA

This is a transclusion of the "History" section of the United States article, for easier viewing and editing. This is not a userspace draft.

Indigenous peoples

[edit]

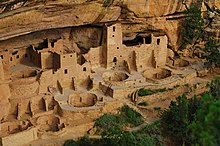

The first inhabitants of North America migrated from Siberia across the Bering land bridge about 12,000 years ago;[2][3] the Clovis culture, which appeared around 11,000 BC, is believed to be the first widespread culture in the Americas.[4][5] Over time, indigenous North American cultures grew increasingly sophisticated, and some, such as the Mississippian culture, developed agriculture, architecture, and complex societies.[6] In the post-archaic period, the Mississippian cultures were located in the midwestern, eastern, and southern regions, and the Algonquian in the Great Lakes region and along the Eastern Seaboard, while the Hohokam culture and Ancestral Puebloans inhabited the southwest.[7] Native population estimates of what is now the United States before the arrival of European immigrants range from around 500,000[8][9] to nearly 10 million.[9][10]

European settlement and conflict (1607–1765)

[edit]

Christopher Columbus began exploring the Caribbean for Spain in 1492, leading to Spanish-speaking settlements and missions from Puerto Rico and Florida to New Mexico and California.[11][12][13] France established its own settlements along the Great Lakes, Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico.[14] British colonization of the East Coast began with the Virginia Colony (1607) and Plymouth Colony (1620).[15][16] The Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established precedents for representative self-governance and constitutionalism that would develop throughout the American colonies.[17][18] While European settlers in what is now the United States experienced conflicts with Native Americans, they also engaged in trade, exchanging European tools for food and animal pelts.[19][a] Relations ranged from close cooperation to warfare and massacres. The colonial authorities often pursued policies that forced Native Americans to adopt European lifestyles, including conversion to Christianity.[23][24] Along the eastern seaboard, settlers trafficked African slaves through the Atlantic slave trade.[25]

The original Thirteen Colonies[b] that would later found the United States were administered as possessions of Great Britain,[26] and had local governments with elections open to most white male property owners.[27][28] The colonial population grew rapidly, eclipsing Native American populations;[29] by the 1770s, the natural increase of the population was such that only a small minority of Americans had been born overseas.[30] The colonies' distance from Britain allowed for the development of self-governance,[31] and the First Great Awakening, a series of Christian revivals, fueled colonial interest in religious liberty.[32]

For a century, the American colonists had been providing their own troops and materiel in conflicts with indigenous peoples allied with Britain's colonial rivals, especially France, and the Americans had begun to develop a sense of self-defense and self-reliance separate from Britain. The French and Indian War (1754–1763) took on new significance for all North American colonists after Parliament under William Pitt the Elder concluded that major military resources needed to be devoted to North America to win the war against France. The British colonies' position as an integral part of the British Empire became more apparent during the war, with British military and civilian officials becoming a more significant presence in American life.

American Revolution and the early republic (1765–1800)

[edit]

Following their victory in the French and Indian War, Britain began to assert greater control over local colonial affairs, resulting in colonial political resistance; one of the primary colonial grievances was a denial of their rights as Englishmen, particularly the right to representation in the British government that taxed them. To demonstrate their dissatisfaction and resolve, the First Continental Congress met in 1774 and passed the Continental Association, a colonial boycott of British goods that proved effective. The British attempt to then disarm the colonists resulted in the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, igniting the American Revolutionary War. At the Second Continental Congress, the colonies appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, and created a committee that named Thomas Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence. Two days after passing the Lee Resolution to create an independent nation the Declaration was adopted on July 4, 1776.[33] The political values of the American Revolution included liberty, inalienable individual rights; and the sovereignty of the people;[34] supporting republicanism and rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and all hereditary political power; civic virtue; and vilification of political corruption.[35] The Founding Fathers of the United States, who included Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, James Madison, Thomas Paine, and many others, were inspired by Greco-Roman, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies and ideas.[36][37]

The Articles of Confederation were ratified in 1781 and established a decentralized government that operated until 1789.[33] After the British surrender at the siege of Yorktown in 1781 American sovereignty was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Paris (1783), through which the U.S. gained territory stretching west to the Mississippi River, north to present-day Canada, and south to Spanish Florida.[38] The Northwest Ordinance (1787) established the precedent by which the country's territory would expand with the admission of new states, rather than the expansion of existing states.[39] The U.S. Constitution was drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention to overcome the limitations of the Articles. It went into effect in 1789, creating a federal republic governed by three separate branches that together ensured a system of checks and balances.[40] George Washington was elected the country's first president under the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791 to allay skeptics' concerns about the power of the more centralized government.[41][42] His resignation as commander-in-chief after the Revolutionary War and his later refusal to run for a third term as the country's first president established a precedent for the supremacy of civil authority in the United States and the peaceful transfer of power.[43][44]

Westward expansion and Civil War (1800–1865)

[edit]

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France nearly doubled the territory of the United States.[45][46] Lingering issues with Britain remained, leading to the War of 1812, which was fought to a draw.[47][48] Spain ceded Florida and its Gulf Coast territory in 1819.[49] In the late 18th century, American settlers began to expand westward, many with a sense of manifest destiny.[50][51] The Missouri Compromise attempted to balance the desire of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery into new territories with that of southern states to extend it, admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. It further prohibited slavery in all other lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30′ parallel.[52] As Americans expanded further into land inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government often applied policies of Indian removal or assimilation.[53][54] The Trail of Tears (1830–1850) was a U.S. government policy that forcibly removed and displaced most Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River to lands far to the west.[55] These and earlier organized displacements prompted a long series of American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi.[56][57] The Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845,[58] and the 1846 Oregon Treaty led to U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest.[59] Victory in the Mexican–American War resulted in the 1848 Mexican Cession of California, Nevada, Utah, and much of present-day Colorado and the American Southwest.[50][60] The California gold rush of 1848–1849 spurred a huge migration of white settlers to the Pacific coast, leading to even more confrontations with Native populations. One of the most violent, the California genocide of thousands of Native inhabitants, lasted into the early 1870s,[61] just as additional western territories and states were created.[62]

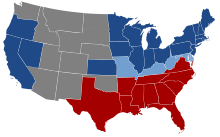

During the colonial period, slavery had been legal in the American colonies, though the practice began to be significantly questioned during the American Revolution.[63] States in the North enacted abolition laws,[64] though support for slavery strengthened in Southern states, as inventions such as the cotton gin made the institution increasingly profitable for Southern elites.[65][66][67] This sectional conflict regarding slavery culminated in the American Civil War (1861–1865).[68][69] Eleven slave states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America, while the other states remained in the Union.[70][71] War broke out in April 1861 after the Confederates bombarded Fort Sumter.[72][73] After the January 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, many freed slaves joined the Union army.[74] The war began to turn in the Union's favor following the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and Battle of Gettysburg, and the Confederacy surrendered in 1865 after the Union's victory in the Battle of Appomattox Court House.[75] The Reconstruction era followed the war. After the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, Reconstruction Amendments were passed to protect the rights of African Americans. National infrastructure, including transcontinental telegraph and railroads, spurred growth in the American frontier.[76]

Post–Civil War era (1865–1917)

[edit]From 1865 through 1917 an unprecedented stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, including 24.4 million from Europe.[79] Most came through the port of New York City, and New York City and other large cities on the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europeans moved to the Midwest. At the same time, about one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec to New England.[80] During the Great Migration, millions of African Americans left the rural South for urban areas in the North.[81] Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867.[82]

The Compromise of 1877 effectively ended Reconstruction and white supremacists took local control of Southern politics.[83][84] African Americans endured a period of heightened, overt racism following Reconstruction, a time often called the nadir of American race relations.[85][86] A series of Supreme Court decisions, including Plessy v. Ferguson, emptied the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of their force, allowing Jim Crow laws in the South to remain unchecked, sundown towns in the Midwest, and segregation in communities across the country, which would be reinforced by the policy of redlining later adopted by the federal Home Owners' Loan Corporation.[87]

An explosion of technological advancement accompanied by the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor[88] led to rapid economic expansion during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, allowing the United States to outpace the economies of England, France, and Germany combined.[89][90] This fostered the amassing of power by a few prominent industrialists, largely by their formation of trusts and monopolies to prevent competition.[91] Tycoons led the nation's expansion in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries. The United States emerged as a pioneer of the automotive industry.[92] These changes were accompanied by significant increases in economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest, creating the environment for labor unions to begin to flourish.[93][94][95] This period eventually ended with the advent of the Progressive Era, which was characterized by significant reforms.[96][97]

Pro-American elements in Hawaii overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy; the islands were annexed in 1898. That same year, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam were ceded to the U.S. by Spain after the latter's defeat in the Spanish–American War. (The Philippines was granted full independence from the U.S. on July 4, 1946, following World War II. Puerto Rico and Guam have remained U.S. territories.)[98] American Samoa was acquired by the United States in 1900 after the Second Samoan Civil War.[99] The U.S. Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917.[100]

Rise as a superpower (1917–1945)

[edit]

The United States entered World War I alongside the Allies, helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers.[101] In 1920, a constitutional amendment granted nationwide women's suffrage.[102] During the 1920s and '30s, radio for mass communication and the invention of early television transformed communications nationwide.[103] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression, which President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to with the New Deal, a series of sweeping programs and public works projects combined with financial reforms and regulations. All were intended to protect against future economic depressions.[104][105]

Initially neutral during World War II, the U.S. began supplying war materiel to the Allies of World War II in March 1941 and entered the war in December after the Empire of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.[106][107] The U.S. developed the first nuclear weapons and used them against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, ending the war.[108][109] The United States was one of the "Four Policemen" who met to plan the post-war world, alongside the United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China.[110][111] The U.S. emerged relatively unscathed from the war, with even greater economic power and international political influence.[112]

Cold War (1945–1991)

[edit]

After World War II, the United States entered the Cold War, where geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union led the two countries to dominate world affairs.[113][114][115] The U.S. utilized the policy of containment to limit the USSR's sphere of influence, and prevailed in the Space Race, which culminated with the first crewed Moon landing in 1969.[116][117] Domestically, the U.S. experienced economic growth, urbanization, and population growth following World War II.[118] The civil rights movement emerged, with Martin Luther King Jr. becoming a prominent leader in the early 1960s.[119] The Great Society plan of President Lyndon Johnson's administration resulted in groundbreaking and broad-reaching laws, policies and a constitutional amendment to counteract some of the worst effects of lingering institutional racism.[120] The counterculture movement in the U.S. brought significant social changes, including the liberalization of attitudes toward recreational drug use and sexuality.[121][122] It also encouraged open defiance of the military draft (leading to the end of conscription in 1973) and wide opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam (with the U.S. totally withdrawing in 1975).[123] A societal shift in the roles of women was significantly responsible for the large increase in female paid labor participation during the 1970s, and by 1985 the majority of American women aged 16 and older were employed.[124] The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the fall of communism and the collapse of the Soviet Union, which marked the end of the Cold War and left the United States as the world's sole superpower.[125][126][127][128]

Contemporary (1991–present)

[edit]

The 1990s saw the longest recorded economic expansion in American history, a dramatic decline in U.S. crime rates, and advances in technology. Throughout this decade, technological innovations such as the World Wide Web, the evolution of the Pentium microprocessor in accordance with Moore's law, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the first gene therapy trial, and cloning either emerged in the U.S. or were improved upon there. The Human Genome Project was formally launched in 1990, while Nasdaq became the first stock market in the United States to trade online in 1998.[129]

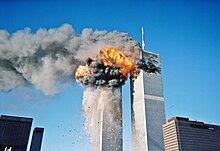

In the Gulf War of 1991, an American-led international coalition of states expelled an Iraqi invasion force that had occupied neighboring Kuwait.[130] The September 11 attacks on the United States in 2001 by the pan-Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda led to the war on terror, and subsequent military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq.[131][132] The cultural impact of the attacks was profound and long-lasting.

The U.S. housing bubble culminated in 2007 with the Great Recession, the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression.[133] Coming to a head in the 2010s, political polarization in the country increased between liberal and conservative factions.[134][135][136] This polarization was capitalized upon in the January 2021 Capitol attack,[137] when a mob of insurrectionists[138] entered the U.S. Capitol and sought to prevent the peaceful transfer of power[139] in an attempted self-coup d'état.[140]

- ^ "Cliff Palace" at Colorado Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 31, 2024

- ^ Erlandson, Rick & Vellanoweth 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Savage 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Waters & Stafford 2007, pp. 1122–1126.

- ^ Flannery 2015, pp. 173–185.

- ^ Lockard 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Johansen, Bruce (2006). The Native Peoples of North America: A History, Volume 1. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3899-0.

- ^ Thornton 1998, p. 34.

- ^ a b Perdue & Green 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Haines, Haines & Steckel 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Davis, Frederick T. (1932). "The Record of Ponce de Leon's Discovery of Florida, 1513". The QUARTERLY Periodical of THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY. XI (1): 5–6.

- ^ Florida Center for Instructional Technology (2002). "Pedro Menendez de Aviles Claims Florida for Spain". A Short History of Florida. University of South Florida.

- ^ "Not So Fast, Jamestown: St. Augustine Was Here First". NPR. February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Petto, Christine Marie (2007). When France Was King of Cartography: The Patronage and Production of Maps in Early Modern France. Lexington Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7391-6247-7.

- ^ Seelye, James E. Jr.; Selby, Shawn (2018). Shaping North America: From Exploration to the American Revolution [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4408-3669-5.

- ^ Bellah, Robert Neelly; Madsen, Richard; Sullivan, William M.; Swidler, Ann; Tipton, Steven M. (1985). Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. University of California Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-520-05388-5. OL 7708974M.

- ^ Remini 2007, pp. 2–3

- ^ Johnson 1997, pp. 26–30

- ^ Ripper, 2008, p. 6

- ^ Ehrenpreis, Jamie E.; Ehrenpreis, Eli D. (April 2022). "A Historical Perspective of Healthcare Disparity and Infectious Disease in the Native American Population". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 363 (4): 288–294. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2022.01.005. ISSN 0002-9629. PMC 8785365. PMID 35085528.

- ^ Joseph 2016, p. 590.

- ^ Stannard, 1993 p. xii

- ^ Ripper, 2008 p. 5

- ^ Calloway, 1998, p. 55

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (1997). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440–1870. Simon and Schuster. pp. 516. ISBN 0-684-83565-7.

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D.; Elliott, Alan C. (2007). Currents in American History: A Brief History of the United States. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1817-7.

- ^ Wood, Gordon S. (1998). The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. UNC Press Books. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-8078-4723-7.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Donald (2013). "The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787–1828". Journal of the Early Republic. 33 (2): 220. doi:10.1353/jer.2013.0033. ISSN 0275-1275. S2CID 145135025.

- ^ Walton, 2009, pp. 38–39

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 35

- ^ Otis, James (1763). The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved. ISBN 978-0-665-52678-7.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1998). The Story of American Freedom (1st ed.). W.W. Norton. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-393-04665-6.

story of American freedom.

- ^ a b Fabian Young, Alfred; Nash, Gary B.; Raphael, Ray (2011). Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation. Random House Digital. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-0-307-27110-5.

- ^ Yick Wo vs. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370

- ^ Richard Buel, Securing the Revolution: Ideology in American Politics, 1789–1815 (1972)

- ^ Becker et al (2002), ch 1

- ^ "Republicanism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. June 19, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Hunter (ed.). "British-American Diplomacy: The Paris Peace Treaty of September 30, 1783". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

- ^ Shōsuke Satō, History of the land question in the United States, Johns Hopkins University, (1886), p. 352

- ^ Foner 2020, p. 524.

- ^ OpenStax 2014, § 8.1.

- ^ Foner 2020, pp. 538–540.

- ^ Boyer, 2007, pp. 192–193

- ^ OpenStax 2014, § 8.3.

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Harriss, Joseph A. "How the Louisiana Purchase Changed the World". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Wait, Eugene M. (1999). America and the War of 1812. Nova Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-56072-644-9.

- ^ "War of 1812". Naval History and Heritage Command. April 10, 2024. Retrieved June 25, 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Klose, Nelson; Jones, Robert F. (1994). United States History to 1877. Barron's Educational Series. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-8120-1834-9.

- ^ a b Carlisle, Rodney P.; Golson, J. Geoffrey (2007). Manifest destiny and the expansion of America. Turning Points in History Series. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-85109-834-7. OCLC 659807062.

- ^ McPherson 1988, p. 41–46.

- ^ Hammond, John Craig (March 2019). "President, Planter, Politician: James Monroe, the Missouri Crisis, and the Politics of Slavery". Journal of American History. 105 (4): 843–867. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaz002.

- ^ Frymer, Paul (2017). Building an American empire : the era of territorial and political expansion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8535-0. OCLC 981954623.

- ^ Calloway, Colin G. (2019). First peoples : a documentary survey of American Indian history (6th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, Macmillan Learning. ISBN 978-1-319-10491-7. OCLC 1035393060.

- ^ McPherson 1988, p. 45.

- ^ Michno, Gregory (2003). Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850–1890. Mountain Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87842-468-9.

- ^ Billington, Ray Allen; Ridge, Martin (2001). Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier. UNM Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8263-1981-4.

- ^ Morrison, Michael A. (April 28, 1997). Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 978-0-8078-4796-1.

- ^ Kemp, Roger L. (2010). Documents of American Democracy: A Collection of Essential Works. McFarland. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7864-4210-2. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ McIlwraith, Thomas F.; Muller, Edward K. (2001). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7425-0019-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^

- Meyer et al. 2001, From 1800 to 1900: "The discovery of gold in California in 1848 proved a momentous watershed for native people in the West. Hordes of single men stampeded to find fortune. Unrestrained by family, community, or church, they decimated the native population near the goldfields. California natives suffered the most complete genocide in U.S. history."

- Wolf, Jessica. "Revealing the history of genocide against California's Native Americans". UCLA Newsroom. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- Madley, Benjamin (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300230697.

- Smithers 2012, p. 339: "The genocidal intent of California settlers and government officials was acted out in numerous battles and massacres (and aided by technological advances in weaponry, especially after the Civil War), in the abduction and sexual abuse of Indian women, and in the economic exploitation of Indian child labourers"

- Blackhawk 2023, p. 38: "With these works, a near consensus emerged. By most scholarly definitions and consistent with the UN Convention, these scholars all asserted that genocide against at least some Indigenous peoples had occurred in North America following colonisation, perpetuated first by colonial empires and then by independent nation-states"

- ^ Rawls, James J. (1999). A Golden State: Mining and Economic Development in Gold Rush California. University of California Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-520-21771-3.

- ^ Walker Howe 2007, p. 52–54; Wright 2022.

- ^ Walker Howe 2007, p. 52–54; Rodriguez 2015, p. XXXIV; Wright 2022.

- ^ Walton, 2009, p. 43

- ^ Gordon, 2004, pp. 27, 29

- ^ Walker Howe 2007, p. 478, 481–482, 587–588.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2004). Atlas of American Military History. Infobase Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4381-3025-5. Retrieved October 25, 2015. Lewis, Harold T. (2001). Christian Social Witness. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-56101-188-9.

- ^ Woods, Michael E. (2012). "What Twenty-First-Century Historians Have Said about the Causes of Disunion: A Civil War Sesquicentennial Review of the Recent Literature". The Journal of American History. 99 (2). [Oxford University Press, Organization of American Historians]: 415–439. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas272. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 44306803. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Silkenat, D. (2019). Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Civil War America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4696-4973-3. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ McPherson 1988, p. 236.

- ^ Vinovskis, Maris (1990). Toward A Social History of the American Civil War: Exploratory Essays. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-39559-5.

- ^ McPherson 1988, pp. 273–274.

- ^ "The Fight for Equal Rights: Black Soldiers in the Civil War". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. August 15, 2016.

By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy.

- ^ Davis, Jefferson. A Short History of the Confederate States of America, 1890, 2010. ISBN 978-1-175-82358-8. Available free online as an ebook. Chapter LXXXVIII, "Re-establishment of the Union by force", p. 503. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2011). Fighting for America: The Struggle for Mastery in North America, 1519–1871. Indiana University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-253-35660-4.

- ^ Price, Marie; Benton-Short, Lisa (2008). Migrants to the Metropolis: The Rise of Immigrant Gateway Cities. Syracuse University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8156-3186-6.

- ^ "Overview + History | Ellis Island". Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island. March 4, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) series C89–C119, pp. 105–109

- ^ Stephan Thernstrom, ed., Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) covers the history of all the main groups

- ^ "The Great Migration (1910–1970)". National Archives. May 20, 2021.

- ^ "Purchase of Alaska, 1867". Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann (1991). Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Drew Gilpin Faust; Eric Foner; Clarence E. Walker. "White Southern Responses to Black Emancipation". American Experience.

- ^ Trelease, Allen W. (1979). White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-313-21168-X.

- ^ Shearer Davis Bowman (1993). Masters and Lords: Mid-19th-Century U.S. Planters and Prussian Junkers. Oxford UP. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-19-536394-4.

- ^ Ware, Leland (February 2021). "Plessy's Legacy: The Government's Role in the Development and Perpetuation of Segregated Neighborhoods". RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 7 (1): 92–109. doi:10.7758/rsf.2021.7.1.06. S2CID 231929202.

- ^ Hirschman, Charles; Mogford, Elizabeth (December 1, 2009). "Immigration and the American Industrial Revolution From 1880 to 1920". Social Science Research. 38 (4): 897–920. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.04.001. ISSN 0049-089X. PMC 2760060. PMID 20160966.

- ^ Carson, Thomas; Bonk, Mary (1999). "Industrial Revolution". Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Gale.

- ^ Riggs, Thomas (2015). Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History Vol. 3 (2 ed.). Gale. p. 1179.

- ^ Dole, Charles F. (1907). "The Ethics of Speculation". The Atlantic Monthly. C (December 1907): 812–818.

- ^ The Pit Boss (February 26, 2021). "The Pit Stop: The American Automotive Industry Is Packed With History". Rumble On. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Tindall, George Brown and Shi, David E. (2012). America: A Narrative History (Brief Ninth Edition) (Vol. 2). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-91267-8, p. 589

- ^ Zinn, 2005, pp. 321–357

- ^ Fraser, Steve (2015). The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power. Little, Brown and Company. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-316-18543-1.

- ^ Aldrich, Mark. Safety First: Technology, Labor and Business in the Building of Work Safety, 1870-1939. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8018-5405-9

- ^ "Progressive Era to New Era, 1900-1929 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Spanish–American War, 1898". Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. New York: Octagon Books, 1975.

- ^ "Virgin Islands History". Vinow.com. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ McDuffie, Jerome; Piggrem, Gary Wayne; Woodworth, Steven E. (2005). U.S. History Super Review. Piscataway, NJ: Research & Education Association. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-7386-0070-3.

- ^ Larson, Elizabeth C.; Meltvedt, Kristi R. (2021). "Women's suffrage: fact sheet". CRS Reports (Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service). Report / Congressional Research Service. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Winchester 2013, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Axinn, June; Stern, Mark J. (2007). Social Welfare: A History of the American Response to Need (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-52215-6.

- ^ James Noble Gregory (1991). American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507136-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015. "Mass Exodus From the Plains". American Experience. WGBH Educational Foundation. 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2014. Fanslow, Robin A. (April 6, 1997). "The Migrant Experience". American Folklore Center. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 5, 2014. Stein, Walter J. (1973). California and the Dust Bowl Migration. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-6267-6. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ The official WRA record from 1946 states that it was 120,000 people. See War Relocation Authority (1946). The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Study. p. 8. This number does not include people held in other camps such as those run by the DoJ or U.S. Army. Other sources may give numbers slightly more or less than 120,000.

- ^ Yamasaki, Mitch. "Pearl Harbor and America's Entry into World War II: A Documentary History" (PDF). World War II Internment in Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Why did Japan surrender in World War II?". The Japan Times. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Pacific War Research Society (2006). Japan's Longest Day. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-4-7700-2887-7.

- ^ Hoopes & Brinkley 1997, p. 100.

- ^ Gaddis 1972, p. 25.

- ^ Kennedy, Paul (1989). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Vintage. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-679-72019-5

- ^ Blakemore, Erin (March 22, 2019). "What was the Cold War?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Mark Kramer, "The Soviet Bloc and the Cold War in Europe," in Larresm, Klaus, ed. (2014). A Companion to Europe Since 1945. Wiley. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-118-89024-0.

- ^ Sempa, Francis (July 12, 2017). Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-51768-3.

- ^ Blakeley, 2009, p. 92

- ^ Collins, Michael (1988). Liftoff: The Story of America's Adventure in Space. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1011-4.

- ^ Winchester 2013, pp. 305–308.

- ^ "The Civil Rights Movement". PBS. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (January 24, 1991). "Great Society". In Eric Foner; John Arthur Garraty (eds.). The Reader's Companion to American History. Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 472. ISBN 0-395-51372-3.

- ^ "Playboy: American Magazine". Encyclopædia Britannica. August 25, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

...the so-called sexual revolution in the United States in the 1960s, marked by greatly more permissive attitudes toward sexual interest and activity than had been prevalent in earlier generations.

- ^ Svetlana Ter-Grigoryan (February 12, 2022). "The Sexual Revolution Origins and Impact". study.com. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Levy, Daniel (January 19, 2018). "Behind the Protests Against the Vietnam War in 1968". Time. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Women in the Labor Force: A Databook" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. p. 11. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Gaĭdar, E.T. (2007). Collapse of an Empire: Lessons for Modern Russia. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 190–205. ISBN 978-0-8157-3114-6.

- ^ Howell, Buddy Wayne (2006). The Rhetoric of Presidential Summit Diplomacy: Ronald Reagan and the U.S.-Soviet Summits, 1985–1988. Texas A&M University. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-549-41658-6.

- ^ Kissinger, Henry (2011). Diplomacy. Simon & Schuster. pp. 781–784. ISBN 978-1-4391-2631-8. Retrieved October 25, 2015. Mann, James (2009). The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War. Penguin. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-4406-8639-9.

- ^ Hayes, 2009

- ^ CFI Team. "NASDAQ". Corporate Finance Institute. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Holsti, Ole R. (November 7, 2011). "The United States and Iraq before the Iraq War". American Public Opinion on the Iraq War. University of Michigan Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-472-03480-2.

- ^ Walsh, Kenneth T. (December 9, 2008). "The 'War on Terror' Is Critical to President George W. Bush's Legacy". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 6, 2013. Atkins, Stephen E. (2011). The 9/11 Encyclopedia: Second Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 872. ISBN 978-1-59884-921-9. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Wong, Edward (February 15, 2008). "Overview: The Iraq War". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2013. Johnson, James Turner (2005). The War to Oust Saddam Hussein: Just War and the New Face of Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7425-4956-2. Retrieved October 25, 2015. Durando, Jessica; Green, Shannon Rae (December 21, 2011). "Timeline: Key moments in the Iraq War". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Hilsenrath, Jon; Ng, Serena; Paletta, Damian (September 18, 2008). "Worst Crisis Since '30s, With No End Yet in Sight". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 1042-9840. OCLC 781541372. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2023.

- ^ Geiger, Abigail (June 12, 2014). "Political Polarization in the American Public". Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ Murray, Mark; Marquez, Alexandra (June 15, 2023). "Here's what's driving America's increasing political polarization". NBC News. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ Hamid, Shadi (January 8, 2022). "The Forever Culture War". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Kleinfeld, Rachel (September 5, 2023). "Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Pape, Robert (January 5, 2022). "American Face of Insurrection: Analysis of Individuals Charged for Storming the US Capitol on January 6, 2021". cpost.uchicago.edu. University of Chicago, Chicago Project on Security and Threats. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim; Becker, Jo; Lipton, Eric; Haberman, Maggie; Martin, Jonathan; Rosenberg, Matthew; Schmidt, Michael S. (January 31, 2021). "77 Days: Trump's Campaign to Subvert the Election". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022.

- ^

- Harvey, Michael (2022). "Introduction: History's Rhymes". In Harvey, Michael (ed.). Donald Trump in Historical Perspective. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003110361-1. ISBN 978-1-003-11036-1.

As with the Beer Hall Putsch, a would-be leader tried to take advantage of an already scheduled event (in Hitler's case, Kahr's speech; in Trump's, Congress's tallying of the electoral votes) to create a dramatic moment with himself at the center of attention, calling for bold action to upend the political order. Unlike Hitler's coup attempt, Trump already held top of office, so he was attempting to hold onto power, not seize it (the precise term for Trump's intended action is a 'self-coup' or 'autogolpe'). Thus, Trump was able to plan for the event well in advance, and with much greater control, including developing the legal arguments that could be used to justify rejecting the election's results. (p. 3)

- Pion-Berlin, David; Bruneau, Thomas; Goetze, Richard B. Jr. (2022-04-07). "The Trump self-coup attempt: comparisons and civil–military relations". Government and Opposition. FirstView (4): 789–806. doi:10.1017/gov.2022.13. S2CID 248033246.

- Castañeda, Ernesto; Jenks, Daniel (April 17, 2023). Costa, Bruno Ferreira; Parton, Nigel (eds.). "January 6th and De-Democratization in the United States". Social Sciences. 12 (4). MDPI: 238. doi:10.3390/socsci12040238. ISSN 2076-0760.

What the United States went through on January 6th was an attempt at a self-coup, where Trump would use force to stay as head of state even if abandoning democratic practices in the U.S. Some advised Trump to declare martial law to create a state of emergency and use that as an excuse to stay in power.

- Eisen, Norman; Ayer, Donald; Perry, Joshua; Bookbinder, Noah; Perry, E. Danya (2022-06-06). Trump on Trial: A Guide to the January 6 Hearings and the Question of Criminality (Report). Brookings Institution. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

[Trump] tried to delegitimize the election results by disseminating a series of far fetched and evidence-free claims of fraud. Meanwhile, with a ring of close confidants, Trump conceived and implemented unprecedented schemes to – in his own words – "overturn" the election outcome. Among the results of this "Big Lie" campaign were the terrible events of January 6, 2021 – an inflection point in what we now understand was nothing less than an attempted coup.

- Eastman v Thompson, et al., 8:22-cv-00099-DOC-DFM Document 260, 44 (S.D. Cal. May 28, 2022) ("Dr. Eastman and President Trump launched a campaign to overturn a democratic election, an action unprecedented in American history. Their campaign was not confined to the ivory tower – it was a coup in search of a legal theory. The plan spurred violent attacks on the seat of our nation's government, led to the deaths of several law enforcement officers, and deepened public distrust in our political process... If Dr. Eastman and President Trump's plan had worked, it would have permanently ended the peaceful transition of power, undermining American democracy and the Constitution. If the country does not commit to investigating and pursuing accountability for those responsible, the Court fears January 6 will repeat itself.").

- Graham, David A. (January 6, 2021). "This Is a Coup". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- Musgrave, Paul (January 6, 2021). "This Is a Coup. Why Were Experts So Reluctant to See It Coming?". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- Solnit, Rebecca (January 6, 2021). "Call it what it was: a coup attempt". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- Coleman, Justine (January 6, 2021). "GOP lawmaker on violence at Capitol: 'This is a coup attempt'". The Hill. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- Jacobson, Louis (January 6, 2021). "Is this a coup? Here's some history and context to help you decide". PolitiFact. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

A good case can be made that the storming of the Capitol qualifies as a coup. It's especially so because the rioters entered at precisely the moment when the incumbent's loss was to be formally sealed, and they succeeded in stopping the count.

- Barry, Dan; Frenkel, Sheera (January 7, 2021). "'Be There. Will Be Wild!': Trump All but Circled the Date". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- Duignan, Brian (2021-08-04). "January 6 U.S. Capitol attack". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

Because its object was to prevent a legitimate president-elect from assuming office, the attack was widely regarded as an insurrection or attempted coup d'état.

- Harvey, Michael (2022). "Introduction: History's Rhymes". In Harvey, Michael (ed.). Donald Trump in Historical Perspective. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003110361-1. ISBN 978-1-003-11036-1.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).