User:Brigade Piron/Antwerp pogrom

The Antwerp pogrom (Dutch: Antwerpse pogrom) was an outbreak of anti-Jewish violence in Antwerp, German-occupied Belgium which took place on 14 April 1941. Jewish shops and businesses were attacked, and two nearby synagogues were pillaged and burnt. Although aided by a faction within the German occupation authorities, the pogrom was both initiated and perpetrated by Flemish collaborationists. It was the only outbreak of disorder during the Holocaust in Belgium.

In the aftermath of the German invasion of May 1940, Belgium was placed under a military occupation administration under the auspices of the German Army which marginalised other bodies such as the Schutzstaffel (SS) and Nazi Party. Although adopting various discriminatory measures in its first months, the occupation authorities considered the issue to be low-priority and wished to encourage the gradual social and economic marginalisation of Jews from Belgian society. It believed that "spectacular actions" against Jews might spark a backlash among the Belgian population and pose a threat to the maintenance of order and alienate bourgeois opinion. However, this view was not shared by the SS and other organs of the German state which had forged their own ties with radical far-right collaborationist factions which had emerged in Flanders.

After a period of increasing agitation by a number of minor collaborationist groups which sought to emphasise the antisemitic credentials, a major antisemitic rally was held in Antwerp on Easter Monday 1941. The participants then marched on the city's Jewish quarter where it ransacked and burned two synagogues and before dispersing into nearby streets to attack Jewish-owned shops and businesses although no-one was killed. Belgian policemen were prevented from intervening, in part, because of the presence of a number of German soldiers in the crowd.

Background

[edit]Jews and the German occupation

[edit]

At the time of the German invasion in May 1940, it is generally estimated that there were between 70,000 and 75,000 Jews living in Belgium out of a largely Catholic population of about eight million.[1] Concentrated in large urban centers, the largest Jewish communities became established in the Flemish port-city of Antwerp and the capital Brussels. The majority were first or second-generation Ashkenazi immigrants from Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe who had sought refuge from antisemitic discrimination and better economic circumstances in the interwar years. Most did not hold Belgian citizenship, and many did not speak French or Dutch.

Antwerp was Belgium's second city and had a long history of Jewish settlement. Before the war, Jews had particular prominence within the city's diamond trade. Jews had generally settled to the East of the city centre, especially around Antwerpen-Centraal railway station and the railway line leading southwards, notably in the working-class neighbourhoods of Kievitwijk and Zurenborg where there are a number of small and medium-sized synagogues.[a] Antisemitic views had become widespread in the interwar years within the city's Catholic circles as well as among trade organisations and among the small far-right milieu and attitudes towards Jews, irrespective of their origin, had become notably more hostile than in Brussels and other Belgian cities.[2] A violent anti-Jewish protest occurred near the station on 25 August 1939.[3] Like many civilians in the country, a substantial number of Belgian Jews fled in the "Exodus" of refugees at the time of the German invasion. There were officially estimated to be 22,500 Jews still living in the city under the Occupation in Autumn 1940 out of a Jewish population estimated at 42,500 across the country as a whole.[4][5]

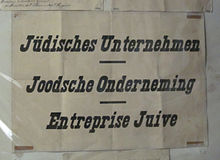

After the invasion, the administration of Belgium had been concentrated in the Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France under the auspices of the German Army (Wehrmacht) which marginalised rival bodies such as the Schutzstaffel (SS) and Nazi Party. The military administration introduced a series of discriminatory legislation through the Belgian Committee of Secretaries-General from 23 October 1940[6] which sought to isolate Jews economically and to exclude them from civic life. Among the measures adopted was a requirement that Jewish-owned shops and businesses be display this fact publicly from November 1940.[4] In spite of this, the administration believed that "spectacular actions" against Jews might spark a backlash among the Belgian population and pose a threat to the maintenance of order and alienate bourgeois opinion. It was therefore content instead to facilitate their gradual social and economic exclusion from the rest of Belgian society.[7] According to the historian Tomasz Szarota, however, "[t]he concept of the military decision makers to solve the "Jewish question" in a gradual manner and on the quiet did not at all meet the expectations of the local nationalist or overtly fascist formations".[8]

Collaborationist groups in Flanders

[edit]In the aftermath of the invasion, the Military Administration sought to cultivate ties with the Flemish Movement. In the pre-war years, the Flemish National League (Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond, VNV) under Staf De Clercq had enjoyed significant electoral success. Authoritarian and clericalist, the patronage of the German authorities permitted the VNV to acquire unprecedented regional influence in exchange for compromising on a number of key tenets of its pre-war ideology and embracing collaborationism. As part of its concessions, the VNV renounced its longstanding central aspiration for Flemish secession and unification with the Netherlands to form a new Greater Dutch state (Dietsland). As well as acquiring a greater measure of institutional power, the VNV was able to consolidate its position in German-occupied Belgium was even able to re-form its paramilitary Black Brigade (Zwarte Brigade). By mid-1941, the VNV had 60,000 members across the region and was only remaining major political movement in Flanders.[8]

Within collaborationist circles, the predominance of the VNV in Flanders was challenged by a range of tiny radical political factions which enjoyed the patronage of the SS but largely ignored by the Military Administration. These groups were more explicitly pro-German than the VNV and drew more directly on Nazi ideology than the VNV. The most notable was the small German-Flemish Working Group (Duitsch-Vlaamsche Arbeidsgemeenschap, known as DeVlag) which had originally been founded as a cultural association and also became was closely associated with the General SS Flanders (Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen), itself founded in September 1940 and also based in Antwerp.[9] Support was also given to even smaller and more quixotic groups such as the tiny single-issue antisemitic People's Defence League (Volksverwering) which had first been established in Antwerp by the lawyer René Lambrichts in 1937.

As collaborationist factions sought to manoeuvre against each other for increasing influence, they used the internal rivalries between different German authorities around the Military Administration and SS. The latter, in particular, distrusted the Catholic and distinctly Flemish ideology of the VNV and lent particular support to DeVlag instead.[9] The Propaganda Department (Propaganda-Abteilung) affiliated to the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, for example, "frequently operated behind the backs of the occupational military authorities and contrary to their position" and also had contacts with DeVlag and the People's Defence League.[10]

Antwerp pogrom

[edit]In the period before Easter in 1941, antisemitic agitation increased noticeably in Antwerp. The historian Lieven Saerens speculates that the intensification may have been encouraged by news of the antisemitic riot by Dutch collaborationist groups in Amsterdam in the German-occupied Netherlands in February the same year.[11] On an initiative from the People's Defence League, the German pseudo-documentary film The Eternal Jew (1940) received a premier at an Antwerp cinema on 6 April 1941. Lambrichts, its leader, had only recently returned to Belgium after attending the official opening of the Institute for Research on the Jewish Question (Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage) in Frankfurt.[12] He gave a speech after the film calling for Jews to be driven out of the country. In its immediate aftermath, there was a noticeable increase in damage to Jewish-owned property in Antwerp. Members of the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen smashed the windows of Jewish shops on the Lange Kievitstraat on 10 April and in the surrounding streets again on 12 April, latterly with the participation of other collaborationist groups.[13]

Pogrom, 14 April 1941

[edit]

On 14 April, Easter Monday, a second, much larger showing of The Eternal Jew took place at the Cinema Rex on De Keyserlei, possibly organised by DeVlag or the People's Defence League. There were at least 1,500 attendees and Lambrichts again gave an inflammatory antisemitic speech.[14] As the audience began to disperse, a small number of individuals in the crowd called on others to follow them in a march towards the nearby Jewish quarter. A crowd of approximately 200 soon formed outside the cinema and, apparently spontaneously, started a march down the Pelikaanstraat and Simonsstraat towards the Jewish quarter.[15]

Although it was presented as spontaneous, the demonstration had in fact been planned in advance by Pieter Verhoeven who was a follower of the local activist Gustaaf Vanniesbecq from the People's Defence League.[16] The participants were predominantly members of VNV's Black Brigades, DeVlag, the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen, and the People's Defence League[b], some wearing their own paramilitary uniforms. The crowd carried banners depicting the skull and crossbones with the caption Juda verrecke (lit. 'Perish Judah').[15] Many were also armed with wooden clubs and metal crowbars.[17] As the crowd proceeded through the streets, it was joined by curious bystanders including some German soldiers on leave in Antwerp wearing their military uniforms.[17]

As the march proceeded, a number of participants attempted to paste posters to the front of a hairdressers calling for a boycott of Jewish shops. After the proprietor protested, the windows of his shop were smashed. Two agents from the municipal police sought to intervene but were told that the marchers were members of the SS and therefore beyond their authority. Several members of the German Military Police (Feldgendarmerie) were also persuaded not to intervene in the disorder.[17] A few minutes later, the crowd reached the two synagogues owned by the Orthodox communities Shomre Hadas and Machsike Hadass, located about 300 metres (980 ft) apart on the Oostenstraat.

The crowd divided and broke into the two synagogues and the home of Rabbi Markus Rottenberg all located on the Oostenstraat. Furniture, sacred books and other cult objects, including Torah scrolls, were thrown into the streets and publicly burned. Within 15 minutes, the buildings had been sacked and were also set on fire.[19] A Belgian policeman who tried to intervene was beaten up by the crowd, and another was threatened with lynching when he tried to demand their identity papers.[20] After this, the mob dispersed into nearby streets such as the Provinciestraat, Mercatorstraat, and Plantin en Moretuslei where they continued to attack Jewish shops and homes, throwing their owners' possessions into the streets.[20] Only after 45 minutes did the Belgian fire services arrive to extinguish the fires.[20]

Aside from the synagogues destroyed in the attack and the rabbi's house, at least 200 shops were damaged in the course of the pogrom. There were no deaths or injuries, however.[21]

Belgian and German response

[edit]

- On 17 April, General Alexander von Falkenhausen ordered German soldiers not to mingle with crowds to enable them to be broken up by the Belgian police.[22]

- Military authorities condemned the riots because they beleived that they would weaken their own authority.[23]

- MAxime STeinberg argues that the pogrom is an attempt by the SS to force the Military Authority into adopting a more radical line on the persecution of the Jews.[24]

- The entire events are filmed by a German film crew from Propaganda Squadron B (Propaganda-Staffel B).[24]

- Locals visited the site in large numbers.[25]

- As punishment, a curfew is imposed on the population although this was soon limited to Jews only.[25]

- "The city council’s lay-judge panel, chaired by officiating mayor Delwaide, resolved to compensate the Jews for their incurred losses from municipal funds. The city recognised itself as responsible for the pillage that had occurred during the riots and the damages caused. They

cited on this occasion a regulation from the French Revolutionary period (from the year 1796!). A year later, the German authorities banned any payments to be made on this basis."[25]

Aftermath

[edit]Although the Antwerp pogrom was the only public outbreak of antisemitic violence in the country, it was followed by an intensification of discriminatory measures and racial persecution. The German authorities ordered the creation of the Association of Jews in Belgium (Vereeniging van Joden in België, VJB; Association des Juifs en Belgique, AJB) as a "Jewish council" which would notionally act on behalf of the Jewish population in its dealings with the German authorities. Importantly, the VJB-AJB was tasked with compiling detailed registers of Jews. As well as further tightening legal restrictions, the German authorities also experimented with the use of Jews for forced labour. Approximately 2,000 Belgian Jews were sent to Northern France to work building fortifications for the Atlantic Wall after June 1942.

The yellow badge was made obligatory for Jews in Belgium from 7 June 1942. The new measure was "an important turning point" which marked the culmination of the longstanding policy of segregating Jews within Belgium and the beginning of a movement towards forced deportation and extermination.[26] Although Belgian municipal authorities in Brussels and Liège refused to assist in the distribution of yellow badges, those in Antwerp actively assisted the policy and later proved more willing to assist the Germans with large-scale raids using the local police.[27] The resistance by the local authorities in Brussels and Liège was the first instance of resistance to persecution of Jews in Belgium.[28]

German policy shifted towards the systematic extermination of European Jews in early 1942 with far-reaching implications across Western Europe. At a meeting on 11 June 1942, Adolf Eichmann informed the leaders of the Security Police/Security Service (Sicherheitspolizei-Sicherheitsdienst, SiPo-SD) from Belgium, France, and the Netherlands that the entire Jewish population of these territories would be deported to Auschwitz concentration camp in German-occupied Poland.[29] The following month, the first contingent of foreign Jews was summoned to the new Mechelen transit camp as a first step to their "evacuation" or "emigration" by rail to Eastern Europe.[30] 24,916 Jews were deported from Belgium between August 1942 and July 1944, of whom only the vast majority were exterminated.[31] Only 1,207 of the deportees survived the war.[citation needed]

Although the proportion of Jews killed in Belgium was lower than the Netherlands, the proportion which survived the war varied significantly by urban centre and significant numbers were able to survive the war in hiding. Antwerp saw the largest proportion of its Jews deported (66%) compared with Brussels (37%), Liège (34%) and Charleroi (38%).[32] The causes of the disparity have been discussed extensively by historians who have pointed to the role of local political cultures and antisemitism, residential segregation, and the degree of collaboration provided by local authorities, especially the police.[33] The pogrom is sometimes referenced as an evidence of Antwerp's "exceptionality" within the Holocaust in Belgium.

References

[edit]- ^ Three religious communities were legally recognised in Antwerp at the outbreak of the Second World War, namely the Communauté israélite d'Anvers (Shomre Hadas), the Communauté orthodoxe (Machsike Hadass), and the Communauté israélite de rite portugais for the small community of Portuguese Jews.

- ^ According to Szarota, there were approximately 100 participants of the People's Defence League.[17] The historian Lieven Saerens cites a figure of 200 to 400 participants from the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen.[18]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Saerens 2005a, p. 160.

- ^ Saerens 2005a, pp. 566–7.

- ^ Saerens 2005a, pp. 556–7.

- ^ a b Szarota 2015, p. 148.

- ^ Saerens 2005a, p. 641.

- ^ Saerens 2005a, p. 586.

- ^ Szarota 2015, pp. 148–9.

- ^ a b Szarota 2015, p. 150.

- ^ a b Szarota 2015, p. 151.

- ^ Szarota 2015, pp. 150–1.

- ^ Saerens 2005a, pp. 665–6.

- ^ Vagman, Vincent. "Rottenberg, Markus". Belgium WWII (in French). CEGESOMA. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Szarota 2015, pp. 151–2.

- ^ Szarota 2015, p. 153.

- ^ a b Szarota 2015, pp. 153–4.

- ^ Saerens 2005a, p. 669.

- ^ a b c d Szarota 2015, p. 154.

- ^ Saerens 2005b, p. 306.

- ^ Szarota 2015, pp. 154–5.

- ^ a b c Szarota 2015, p. 155.

- ^ Schram, Laurence. "De « mini-pogrom van Antwerpen » - 14 april 1941". Kazerne Dossin Memorial (in Flemish). Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Szarota 2015, p. 156.

- ^ Szarota 2015, pp. 156–7.

- ^ a b Szarota 2015, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Szarota 2015, p. 158.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, pp. 547–8.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, p. 555.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, p. 660.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, p. 571.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, pp. 571–2.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, p. 643.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, pp. 643–5.

- ^ Belgique docile 2007, pp. 645–56.

Bibliography

[edit]- Van Doorslaer, Rudi; Debruyne, Emmanuel; Seberechts, Frank; Wouters, Nico (2007). La Belgique docile: les autorités belges et la persécution des Juifs en Belgique durant la seconde guerre mondiale. Vol. 1. Brussels: Editions Luc Pire. ISBN 9782874158483.

- Szarota, Tomasz (2015). On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms in Occupied Europe (PDF). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7.

- Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- Saerens, Lieven (2005b). "Gewone Vlamingen ? De jodenjagers van de Vlaamse SS in Antwerpen, 1942 (Part I)". Bijdragen tot de Eigentijdse Geschiedenis (15): 289–313.

- Saerens, Lieven (2005a). Étrangers dans la cité : Anvers et ses Juifs (1880-1944). Brussels: Éditions Labor. ISBN 2-8040-1833-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Saerens, Lieven (2000). Vreemdelingen in een wereldstad: een geschiedenis van Antwerpen en zijn joodse bevolking (1880-1944). Tielt: Lannoo. pp. 568–75. ISBN 9789020941098.

External links

[edit]- Hannes, Pieters. "De Antwerpse 'Kristallnacht'". Belgium-WWII (in Dutch). CEGESOMA. Retrieved 27 June 2022.