User:Artem.G/sandbox3

El Lissitzky | |

|---|---|

El Lissitzky in a 1924 self-portrait | |

| Born | Lazar Markovich Lissitzky 23 November 1890 |

| Died | 30 December 1941 (aged 51) |

| Signature | |

| |

El Lissitzky (Russian: Эль Лиси́цкий, born Lazar Markovich Lissitzky Russian: Ла́зарь Ма́ркович Лиси́цкий, ⓘ; 23 November [O.S. 11 November] 1890 – 30 December 1941), was a Jewish-Russian artist, active as a printmaker, painter, illustrator, designer, photographer, and architect. He was an important figure of the Russian avant-garde, helping develop suprematism with his mentor, Kazimir Malevich, and designing numerous exhibition displays and propaganda works for the Soviet Union.

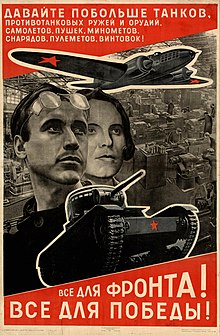

Lissitzky began his career illustrating Yiddish children's books in an effort to promote Jewish culture in Russia. When only 15 he started teaching, a duty he would maintain for most of his life. Over the years, he taught in a variety of positions, schools, and artistic media, spreading and exchanging ideas. He took this ethic with him when he worked with Malevich in heading the suprematist art group UNOVIS, when he developed a variant suprematist series of his own, Proun, and further still in 1921, when he moved to Weimar Republic. In his remaining years he brought significant innovation and change to typography, exhibition design, photomontage, and book design, producing critically respected works and winning international acclaim for his exhibition design. This continued until his deathbed, where in 1941 he produced one of his last works – a Soviet propaganda poster rallying the people to construct more tanks for the fight against Nazi Germany.

Early years

[edit]

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky was born on 23 November 1890[a] in Pochinok, a small Jewish community 50 kilometres (31 mi) southeast of Smolensk, Russian Empire.[2] His father Mordukh (Mark) Zalmanov was well-educated travel agent who know English and German languages, "in his spare time he translated Heine and Shakespeare".[2][b] He emigrated to America, but returned to Russia as his wife's rabbi advised against emigration. Lissitzky's mother Sarah strictly observed Jewish religious traditions.[3][c] From 1891 to 1898 Lissitzky's family lived in Vitebsk, where Lazar's brother and sister were born.[2]

In 1899 Lazar moved to Smolensk, where he lived with his grandfather and attended City School 1.[4] In 1903, during a summer vacation he spent with his parents in Vitebsk, he started to receive instruction from Yury Pen, a famous Jewish artist and teacher. Marc Chagall and Ossip Zadkine were also Pen's students.[4] By the time Lissitzky was 15 he was teaching students himself; he later recalled in his diary that "[a]t age fifteen I began to earn a living by tutoring and drawing."[4]

He applied to the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts in 1909, but was rejected, possibly because he failed the exams or due to the "Jewish quota" under the Tsarist regime that limited the number of Jewish students in Russian schools.[5][6] Instead, in 1909 he moved to Germany to study architectural engineering at the Darmstadt Polytechnic Institute. His wife later wrote that while studying Lissitzky "earned extra money by doing examination projects for fellow-students who were either too lazy or too inept to do their test-pieces for themselves".[5] He also worked as a bricklayer, and visited local Jewish historical sites on vacations, like the medieval Worms Synagogue, of which he made drawings of the interior and decorations.[5]

Lissitzky had travelled to Paris and Belgium during 1912, and spent several months in St. Petersburg. In 1913 he went to a tour of Italy; he wrote in his diary that "I covered more than 1,200 kilometers in Italy on foot – making sketches and studying."[7] He graduated cum laude from Darmstadt Polytechnic in 1914 . When World War I began, Lissitzky returned to Russia via Switzerland and Balkans; and in 1915 started studies at Riga Polytechnic Institute, that was evacuated to Moscow, and started to participate in exhibitions.[8] He also started to work for the architectural firms of Boris Velikovsky and Roman Klein.[7] Klein was also a Egyptologyst, and he was responsible for creating the Egyptian Department of the Pushkin Museum. Lissitzky also took part in arranging this exhibition.[9]

Jewish period

[edit]Much of Lissitzky's childhood was spent in Vitebsk, large city with affluent Jewish life. The art historian Igor Dukhan noted that "there were Litvaks, Hasidim, and early Jewish bourgeoisie, as well as public organizations of diverse and even contradictory character – a Jewish literary–musical society, a Society for the Enlightenment of Jews in the Russian Empire, a Society for Jewish Language, as well as Bundist and Zionist-oriented groups".[10][d] Lissitzky spent his childhood and youth near the Pale of Settlement; art historian Nancy Perloff noted that it influenced him because of "a powerful Jewish solidarity, the community-wide response to the knowledge that Jews would never be considered true Russians".[11]

While in Darmstadt, Lissitzky travelled to Worms to study its medieval synagogue, when he returned to Russia he became involved in a Jewish artistic circle.[10] In 1917, he became secretary of the organizing committee of the Moscow Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture by Jewish Artists.[8] After the Revolution the Tsarist 1915 decree that prohibited usage of Hebrew lettering in print was abolished,[12] and Jews acquired the rights as any other people of the former Russian Empire. Lissitzky moved to Kiev in 1917, and started to work with Yiddish book design.[11] One of the goals of Lissitzky and his Jewish colleagues was an attempt to create new, secular Jewish culture;[13] one of his main ideas and desires of that time was creation of "an all-inclusive art and culture in Russia".[14]

Ethnographic expeditions

[edit]

In 1916, Lissitzky and his artist-colleague Issachar Ber Ryback undertook an ethnographic expedition to Jewish shtetls, possible funded by S. An-sky's Jewish Historical Ethnographic Society.[11] They toured a number of cities and towns of the Belarusian Dnieper region and Lithuania in order to identify and document monuments of Jewish antiquity. Lissitzky was particularly impressed by the Cold Synagogue in Mogilev; he made several drawings of its decorations and interior, and in 1923 wrote an article for Berlin-based Jewish journal Rimon-Milgroim: "On the Mogilev Shul: Recollections".[15][16][11] In the article, Lissitzky compared his visit to Mogilev synagogue with visits to "Roman basilicas, Gothic chapels, or baroque churches".[10] He went on to praise Chaim Segal, the creator of the synagogue's interior murals:[15][11]

The walls—wooden, oaken beams that resound when you hit them. Above the walls, a ceiling like a vault made out of boards. The seams all visible. ... the whole interior of the shul is so perfectly conceived by the painter with only a few uncomplicated colors that an entire grand world lives there and blooms and overflows this small space. The complete interior of the shul is decorated, starting with the backs of the benches, which cover the length of the walls, all the way to the very pinnacle of the vault. The shul, which is a square at the level of the floor, becomes an octagonal vaulted ceiling, resembling a yarmulke. ... These walls and ceiling are structured with an immense feel for composition. This is something completely contrary to the primitive. This is the fruit of a great culture. Where does it come from? The master of this work, Segal, says in his inscription, full of the most noble enthusiasm: "Long already have I wandered through the world of the living..."

Yiddish children's book design

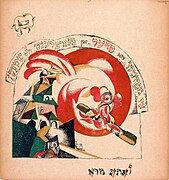

[edit]Lissitzky's first book design was Moishe Broderzon's 1917 Sikhes khulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An Everyday Conversation: A Story, also called The Legend of Prague), created in a form of a Torah scroll.[17] The book was printed in 110 copies. Lissitzky explained in the colophon that he "intended to couple the style of the story with the 'wonderful' style of the square Hebrew letters." In 1918 he illustrated Mani Leib's book Yingl Tsingl Khvat (The Mischievous Boy), incorporating typography into the illustrations.[11][f] Lissitzky created ten illustrations for the book; for each page he arranged text and his drawings differently.[18]

Scholars trace Lissitzky's style of the book to be inspired by his earlier expedition to the shtetls and by Chagall. The first illustration features a Christian church and beys-medresh to show peaceful coexistence of Christians and Jews mentioned by Mani Leib; a goat and a pig in the bottom symbolizes Jews and Christians.[19] Another illustration was described as "reminiscent of Ryback ... while the Jew sitting at the table, the clock on the wall and the window cut in cubist triangles bear a resemblance to some of Chagall's interiors."[19] Scholars note that Lissitzky greatly expanded the meanings of Leib's book, his "brave Tsingl corresponds to the numerous mounted heroes of the Russian fairy tales and the traditional oral epic bylina which ... were a source of inspiration for leading Russian artists like Ivan Bilibin or Viktor Vasnecov. Lissitzky is too much aware of this double cultural heritage not to use its visual potential. ... Lissitzky's Tsingl grows out of a double Slavic-Jewish oral and visual tradition and ... responds to the requirements of modern Jewish art combining avant-garde techniques and Jewish folk art."[19]

In 1918, Lissitzky together with Joseph Chaikov, Issachar Ber Ryback, Mark Epstein and some others founded the art section of the Kultur-Lige movement in Kiev.[20]

In 1917 and 1919 Lissitzky created two variants of the book Had Gadya (The Only Kid), a ten-verse Aramaic song based on a German ballad, singed in a conclusion of a Passover seder. The song tells a story of a young goat purchased by a father, who was eaten by a cat; the song continues to talk about the succession of attackers until God destroys the final aggressor. The song is usually considered as an allegory for the oppression and execution of the Jews, with attackers being different peoples mistreating Jews throughout history.[21] Lissitzky used Yiddish for the book verses, but introduced each verse in a traditional Aramaic, written in Hebrew alphabet.[11] These two versions differ in style: art historians Igor Dukhan and Nancy Perloff called the 1917 version "an expressionist decorativism of color and narrative"[10] and "a set of brightly colored, folklike watercolors",[11] respectively, and 1919 version being "marked by a stylistic shift".[10]

Two versions also differ in narrative: in the earlier book the Angel of Death is "cast down but still alive", in the later one he is definitely dead, his victims are resurrected. Dukhan treats these differences as Lissitzky's sympathies towards the October Revolution, after which Jews of the Russian Empire were liberated from discrimination.[10] Perloff also thinks that Lissitzky "viewed the song both as a message of Jewish liberation based on the Exodus story and as an allegorical expression of freedom for the Russian people." Several researched noted a similarity between Lissitzky's drawing and first stamp issued in Soviet Russia, with a hand gripping a sword under the Sun, as a symbol of new Soviet people. The Angel of Death is depicted crowned, symbolically linked to the tzar, "killed by the force of revolution";[11] by merging the hand of God with the hand of Soviet people, Lissitzky "implies a divine component to the revolution ... but also suggests that the oppressive czarist monarchy ... was rendered powerless in the face of revolutionary Justice".[22][23][20] Above the angel's palm are Hebrew letters pei-nun, used on Jewish tombstones and meaning "here lies".[24] Art historian Haia Friedberg notes that the illustration closely resemble the binding of Isaac, but Lissitzky impose quite different meaning:

instead of Isaac being under the knife ... it is the Angel of Death who is being killed by the hand of god. One should not be mistaken in thinking that there is identification between Isaac and the Angel of Death; on the contrary: Isaac, and the kid are saved from the hand of death because death itself is killed. Recognizing young Russian Jews—raised traditionally and living in a revolutionary age—as his target audience, Lissitzky brilliantly chooses Had Gadya as the medium of his message. Through the story and characters of the Had Gadya, he offers the choice that he himself made: to leave the old ways paved with victimization in favor of the new redemptive path of the revolution and communism, a gift offered from heaven itself.[24]

Some illustrations are not mentioned in the song, for example the red rooster in the scene five; Yiddish saying royter henn, literally 'red rooster', also means 'arson'.[25] The cover of 1919 edition was designed in abstract suprematist forms.[10]

Perloff praised the book as a novel approach to typography and design, and noted Lissitzky's usage of colors:

Lissitzky invented a system of color coding in which the color of the principal character in each illustration matches the color of the corresponding word for that character in the Yiddish text. For instance, the kid in verse 1 is yellow, and the Yiddish word ציגעלע (kid) in the arch above is also yellow; the green hue of the father's face is matched by the green type used for the Yiddish word טאטע (father). While the bold colors and two-dimensionality of the lithographs are reminiscent of Chagall's work, the formal properties of the illustrations are also Cubistic in their use of geometric forms and Futuristic in their use of the spiral to evoke motion.[11]

Dukhan called Had Gadya "a quintessence of El Lissitzky's post revolutionary Jewish Renaissance inspiration".[10] Perloff also sees the book as "culmination of his artistic and personal engagement with Judaica".[11] Visual representations of the hand of God would recur in numerous pieces throughout his entire career, most notably with his 1924 self-portrait The Constructor,[26] but also in 1922 illustration for Shifs-Karta, and 1927 VKhUTEMAS book cover.[27][g]

Lissitzky continued to illustrate Yiddish books, he worked on Leib Kvitko's Ukraynishe Folkmayses (Ukrainian folktales) and Vaysrusishe Folkmayses (Belarusian folktales).[28] Both books were published in Berlin in 1922 and 1923, but based on the style of illustrations scholars consider both books to be created before 1919. The style is "unmistakably modernist, with strongly shaded figures and resolutely flat backgrounds".[29] Yiddish translation of Rudyard Kipling's book The Elephant's Child, or Elfandl, illustrated by Lissitzky, was published in Berlin in 1922; scholars note "clear parallels" between folktale illustrations and the Kipling ones. The book is not colored except for its cover; Lissitzky's illustrations was also interpreted as having a symbolic ties to Revolution:[29]

Enclosed in a black and red frame is a sideways depiction of the little elephant, set in a red circle beneath the title, whose typographical design is also in black and red. The elephant (already in possession of its trunk) is strutting out to the right as if urging the reader to turn the page. ... the little elephant is a vigorous child of the Revolution, marching confidently into the future, its trunk lifted high. ... While entirely faithful to Kipling's text, Lissitzky's illustrations create a pictorial subtext that turns the 'Just So' story about the elephant's child 'full of satiable curiosity' into a revolutionary tale in which the young elephant successfully rebels against the established order and thereby brings about an improved society for all.[29]

One of the last Yiddish books that Lissitzky worked on was 1922 Arba'ah Teyashim (Hebrew: אַרְבָּעָה תְיָשִים; Four Billy Goats).[30][31]

The end of the Jewish period

[edit]

Jewish period was rather short for Lissitzky; he illustrated the last Jewish book in 1923.[32] In April 1919 a decree issued by the new Soviet state (by Joseph Stalin with support of Yevsektsiya leader Samuil Agurskii), "abolished the elected local communal units of Jewish life, the kehillas in the Ukraine".[33] The second decree issued in June designated all Jewish organizations as "enemies of the revolution", after that all synagogues and Jewish cultural organizations were closed.[34][33] Usage of Hebrew letters and the Yiddish language was now called "anti-communist"[33] and was "regarded as cultural separatism".[35][h] As art historian Eva Forgács wrote, "that autumn, Eliezer (Lazar) Lissitzky abandoned his Judaic heritage and became El Lissitzky. It is unclear if the name change was legal or merely an appropriate pseudonym."[34] For Shatskikh this name change signifies the "'abrupt and total' shift from the creation of explicitly Jewish works to the production of abstract, non-ethnic universalist art."[36]

Jewish themes and symbols sometimes appeared in his later works: scholars found connections between his photomontage called The Constructor and Kabbalah,[37] his Figurinnenmappe (Traveler All Over the Time) was linked to Ahasver, "the everlasting Jew",[38] Hebrew letters were used in a number of Prouns and book covers he made, such as an illustration for Ilya Ehrenburg's story Shifs-Karta (Yiddish: שיפֿס קאַרטע; Passenger Ticket).[38][39] The illustration is a "photogram of the open hand with two Hebrew letters – 'pe' and 'nun' (traditional Jewish tombstone initials for "here lies"). In the foreground is the schedule of the New York–Hamburg and Hamburg–New York sea routes, a ship sailing to America, an American flag, and a framing Magen David".[40] The illustration was interpreted as "the end of Jewish wandering as well as the persistence of traditional Jewish beliefs."[39] Dukhan sees this work as an "intermediate play" between Lissitzky's "Jewish expressionism of the late 1910s" and the abstract language of the 1920s.[41] Nisbet interprets the black hand to be the hand of "pogrom-instigators", both "the Whites and the Communists, both of whom wish to eradicate the culture of the shtetl".[42]

Art historian Victor Margolin doubts Lissitzky's embrace of Revolution. Though Lissitzky bragged that he designed the flag for the All-Union Central Executive Committee "which was carried across Red Square on the first of May 1918",[43] there is no other evidence of that.[44] Despite this fact, Margolin writes that because of his Jewish origins Lissitzky was conspicuous of communists, who had an anti-Jewish position and a tendency of assimilation; he also was in opposition to Yevsektsiya, "who believed that Jews should be Communists first and nationals second". Lissitzky's writings also do not show the his support of Communism; in one of his essays he even wrote that Suprematism will surpass Communism.[43] According to Forgács, "Suprematism ... as Lissitzky saw it, straddled loyalty to the communist Soviet state and the desire to not betray Jewish culture: its vision of the future was distant and universal, projected far ahead into the cosmos ..."[45]

Avant-garde period

[edit]Suprematism and Vitebsk Art School

[edit]In May 1919 Lissitzky returned to Vitebsk when Marc Chagall invited him to teach graphic arts, printing, and architecture at the newly formed People's Art School – a school that Chagall created after being appointed Commissioner of Artistic Affairs for Vitebsk in 1918. Lissitzky was engaged in designing and printing propaganda posters and illustrations for a local Vitebsk newspaper; later, he never mentioned his works of this period, probably because he portrayed Leon Trotsky and other early revolutionaries, who later became enemies of the Soviet state. The quantity of these posters is sufficient to regard them as a separate genre in the artist's output.[46]

Chagall also invited other Russian artists, most notably the painter and art theoretician Kazimir Malevich and his and Lissitzky's former art teacher, Yehuda Pen. However, it was not until October 1919 when Lissitzky, then on an errand in Moscow, persuaded Malevich to relocate to Vitebsk.[47] Malevich would bring with him a wealth of new ideas, most of which inspired Lissitzky but clashed with local public and professionals who favored figurative art and with Chagall himself.[48] After going through impressionism, primitivism, and cubism, Malevich began developing and advocating his ideas on suprematism. In development since 1915, suprematism rejected the imitation of natural shapes and focused more on the creation of distinct, geometric forms. He replaced the classic teaching program with his own and disseminated his suprematist theories and techniques school-wide. Chagall advocated more classical ideals and Lissitzky, still loyal to Chagall, became torn between two opposing artistic paths. Lissitzky ultimately favoured Malevich's suprematism and broke away from traditional Jewish art. Chagall left the school shortly thereafter.[49]

Chagall later recalled it in his memoirs: "My most zealous disciple swore friendship and devotion to me. To hear him, I was the Messiah. But at the moment he was appointed professor, he went over to my opponents' camp and heaped insults and ridicule on me."[50]

At this point Lissitzky subscribed fully to Suprematism and, under the guidance of Malevich, helped further develop the movement. Lissitzky designed Malevich's book On the New System in Art, that was printed in 1,000 copies – enormous number for the art book.[51] Malevich scribed a note on Lissitzky's copy of the book "With the appearance of this booklet, I greet you, Lazar Markovich. It will be the trace of my path and the beginning of our collective movement."[52]

UNOVIS

[edit]

On 17 January 1920, Malevich and Lissitzky co-founded short-lived Molposnovis group (Russian: МОЛодые ПОСледователи НОВого Искусства, Young followers of a new art), a proto-suprematist association of artists. After a brief and stormy dispute and two rounds of renaming, the group reemerged as UNOVIS (Russian: Утвердители НОВого ИСкусства, Exponents of the New Art) in February.[53]

The group, disbanded in 1922, was pivotal in the dissemination of suprematist ideology in Russia and abroad and launch Lissitzky's status as one of the leading figures in the avant-garde. Incidentally, the earliest appearance of the signature 'El Lissitzky' (Russian: Эль Лисицкий) emerged in the handmade UNOVIS Miscellany, issued in two copies in March–April 1920.[54] The origin of Lissitzky's new name is unclear. Art historian Alexandra Shatskikh noted that UNOVIS' motto, a nonsense line from Malevich's book On New Systems in Art, "U-el-el'-ul-el-te-ka", can be a source of the new name "El".[55]

Under the leadership of Malevich UNOVIS worked on a "suprematist ballet", choreographed by Nina Kogan and on the remake of a 1913 futurist opera Victory Over the Sun by Mikhail Matyushin and Aleksei Kruchenykh.[56] All members of UNOVIS shared credit for the works produced within the group, signing most pieces with a black square. This was partly a homage to a similar piece by their leader, Malevich, and a symbolic embrace of the Communist ideal. This would become the de facto seal of UNOVIS that took place of individual names or initials. Black squares worn by members as chest badges and cufflinks also resembled the ritual tefillin and thus were no strange symbol in Vitebsk shtetl.[57] Lissitzky himself used a red square as a seal, all other group members used black.[58][i] Shatskikh compares UNOVIS with the Bauhaus school, who's founder, Walter Gropius, said that a "joyfully creating commune, for which the Masonic lodges of the Middle Ages are the ideal prototype". UNOVIS had a motto, rituals, program, and an emblem; its leader, Malevich, wore white clothes and a white hat as symbols of Suprematism.[58] Malevich himself said that it was modelled after a research laboratory.[59]

In April 1920 UNOVIS was asked to produce decorations for the celebrations of the Workers Day, May 1. They decorated the whole city with suprematistic decorations, made drawing on buildings and on trams, and wrote Communism mottos. Sergei Eisenstein, who was in the city with a brief visit, later described it:[60][61]

A singular provincial town. Built, like so many of the towns in the west of the country, of red brick. Begrimed with soot and depressing. But there is something very odd about this town. In the main streets the red bricks are painted white. And over this white background there are green circles everywhere. Orange squares. Blue rectangles. This is Vitebsk in the year 1920. The brush of Kasimir Malevich has gone over the brick walls. ... You see orange circles before your eyes, red squares and green trapeziums. ... Suprematist confetti strewn about the streets of an astonished town.[62]

In 1920 Lissitzky left Vitebsk for Moscow and became member of INKhUK (the Institute of Artistic Culture); in 23 September 1921 he gave a lecture there about his Prouns. In 1921 he also started to teach at Vkhutemas, but soon left Moscow for Germany; he stayed in Berlin for several years.[63]

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge

[edit]Perhaps the most famous work by Lissitzky from that period was the 1919 propaganda poster "Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge". Russia was going through a civil war at the time, which was mainly fought between the "Reds" (communists, socialists and revolutionaries) and the "Whites" (monarchists, conservatives, liberals and other socialists who opposed the Bolshevik Revolution). The name can also be derived from antisemitic pogrom slogan "Beat the Jews!"[j][64][65] According to Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, in 1945 Pablo Picasso declared that the "painting was not invented for decorating houses, but as a weapon of attack and defence".[66]

Art historian Maria Elena Versari connected Lissitzky's poster with Italian Futurism manifesto Futurist Synthesis of War, published in 20,000 copies in 1914, and signed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Ugo Piatti. Lissitzky never mentioned the manifesto, but his friend and colleague Malevich met Marinetti in 1914, and even called him one of the "two pillars, the two 'prisms' of the new art of the twentieth century".[k] Also in 1918, young architect Nikolai Kolli created The Red Wedge monument in Moscow, that "consisted of a red triangle vertically inserted as a wedge into a white rectangular block. A very visible crack snakes downward from the tip of the triangle, suggesting that the force of the red wedge has succeeded in breaking the solidity of the white structure. The abstract metaphor was intended to signify the victory of the Red Army over the White, counter-Revolutionary forces." The monument was initially erected as a symbol of victory over White general Pyotr Krasnov, an important early triump of the Red Army. Versari argues that Lissitzky "adopted an almost identical language" for his Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, though he never mentioned it.[67]

Lissitzky later used similar idea, a wedge in a circle, for a cover of Yiddish magazine Apikojres ('Atheist'). As Artur Kamczycki writes, "Apikojres is a heretic – a Jew who does not believe in revelation and negates traditional religion and will therefore not have a share in the world to come and is bound for eternal damnation. In Yiddish, this word is often used to describe someone who has opinions that contradict the orthodox doctrine. Lissitzky suggests here that a revolution requires sacrifice and transformations in the name of the new, better world."[68] He also noted that Lissitzky believed in the forces of Revolution and combined it with a messianic elements of Judaism, writing:

The intellectuals, the highly-educated, were expecting the 'new era' to arrive in the shape of a Messiah, with aureole and white robes, with manicured hands, mounted on a white horse. But in reality the new era came in the shape of the Russian Ivan, with tousled hair, tattered and dirty clothes, barefoot, and with hands that were bleeding and torn by work. These people did not recognize the new era in an apparition like this. They turned their backs on him, ran away and hid. Only the youngest stayed put. But this youngest generation was not born in October 1917; the October Revolution in art originated much earlier.[69]

Return to Germany

[edit]

In 1921, roughly concurrent with the demise of UNOVIS, suprematism was beginning to fracture into two ideologically adverse halves, one favoring Utopian, spiritual art and the other a more utilitarian art that served society. Lissitzky was fully aligned with neither and left Vitebsk in 1921. He took a job as a cultural representative, "cultural emissary", of Soviet Russia and moved to Weimar Berlin where he was to establish contacts between Russian and German artists.[70] What he had done in this role is still unclear.[71] Post-war Berlin was a cultural center, with an enormous number of Russian émigrés, estimated between 300,000 and 560,000 in 1920-1921, with Vladimir Nabokov, Boris Pasternak, Alexander Blok, Aleksey Tolstoy, Ilya Ehrenburg, Marina Tsvetaeva, Andrei Biely, Viktor Shklovsky, Roman Jakobson, Ivan Puni, Ksenia Boguslavskaya, Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, Vasily Kandinsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Lily and Osip Brik, and Sergei Esenin among them.[72][l]

Lissitzky worked as a writer and designer for international magazines and journals while helping to promote the avant-garde through various gallery shows. He started the very short-lived magazine Veshch/Gegenstand/Objet with Russian-Jewish writer Ilya Ehrenburg,[73] that intended to display contemporary Russian art to Western European audience. It was a wide-ranging publication, mainly focused on new suprematist and constructivist works, and was published in German, French, and Russian.[74][75] Two issues of the magazine were published in 1922. The magazine is considered to be a continuation of UNOVIS ideas.[73] In the first issue, Lissitzky wrote:

We hold that the fundamental feature of the present age is the triumph of the constructive method. We find it just as much in the new economics and the development of industry as in the psychology of our contemporaries in the world of art. Objet will take the part of constructive art, whose task is not to adorn life but to organize it.[76]

The magazine, though short-lived, became influential. Besides Russians, articles by Blaise Cendrars, Le Corbusier, van Doesburg, Viking Eggeling, Carl Einstein, Fernand Léger, Lajos Kassák, and Ljubomir Micić were published in the first issue.[77]

In 1923 Lissitzky designed (or "constructed" in his words) the book Dlia Golosa ("For the Voice"), a collection of Vladimir Mayakovsky's poems. This book was called a "masterpieces of modernist typographic design" even during the time of its publication. Lissitzky acknowledged that his work on the book "won him election to membership" in the Gutenberg Society.[78]

In Berlin Lissitzky also met and befriended other artists, most notably Kurt Schwitters, László Moholy-Nagy, and Theo van Doesburg.[79] Together with Schwitters and van Doesburg, Lissitzky presented the idea of an international artistic movement under the guidelines of constructivism while also working with Kurt Schwitters on the issue Nasci (Nature) of the periodical Merz. The year after the publication of his first Proun series in 1921, Schwitters introduced Lissitzky to the Hanover gallery Kestnergesellschaft, where he held his first solo exhibition. The second Proun series, printed in Hanover in 1923, was a success.[75] Later on, he met Sophie Küppers—the widow of Paul Küppers, an art director of the Kestnergesellschaft—whom he would marry in 1927.[80]

Prouns

[edit]

In 1919-1920, Lissitzky proceeded to develop a suprematist style of his own, a series of abstract, geometric paintings which he called Proun (pronounced "pro-oon", "UNOVIS Project", Russian: ПРОект УНовиса).[84][m] He rejected any specific orientation of Prouns, and "intended them to have neither top nor bottom";[85] commenting on it he wrote "We have made the canvas rotate. And as we rotated it, we saw that we were putting ourselves in space."[86] Prouns were his own, architectural version of suprematism, he also took a lot from the Russian constructivist movement.[87] Describing Prouns he used a lot of constructivism terms such as 'space', 'concrete', 'construct', and 'construction', and described them to be "like a geographical map, like a design".[88]

In 1923, Lissitzky published the so-called Kestnermappe (Kestner Portfolio or Proun Portfolio), that included six lithographs and was published in fifty copies.[89][n]

Art historian Alan C. Birnholz noted that "the Proun compositions gradually turned away from color, displayed a growing sense of clarity and economy, and/or tended to diffuse the areas of tension in the formal interrelationship over the entire picture surface." Proun compositions were described as "a problem in the definition of space." He also ties the series with Lissitzky's searches for a new order, "For Lissitzky, the "cosmic space" of the Prouns came to symbolize the utopia he envisioned in the new social order of the Revolution."[90]

Lissitzky himself described Prouns as:

Cubism moves along tracks laid on the ground; the construction of Suprematism follows the straight lines and curves of the aeroplane ... PROUN leads us to construct a new body ... A PROUN begins as a level surface, turns into a model of three-dimensional space [räumlichen Modellbau], and goes on to construct all the objects of everyday life. [It is] a stopping point on the path of constructing a new form.[91]

Lissitzky rejected any definition of what exactly is Proun, writing "I cannot give an absolute definition of what Proun is, because the work is not yet dead."[92] He did not see the Prouns as mere drawings, comparing "the artist who creates Proun works to the scientist who combines chemical elements to make an acid, which is no mere laboratory experiment, but is strong enough to affect all aspects of life."[93] At one point he asserted that Prouns are the "communist foundation of steel and concrete for all the people of the earth."[88]

Prouns were Lissitzky's attempt to depart from Malevich's suprematism, he did it by adding the illusory third dimension to previously plain works. As Forgács wrote,

He adopted Malevich's cosmic void, although he did not paint it white, but insisted on painting voluminous floating geometric objects, thereby rationalizing suprematism inasmuch as he tended to reveal the entire body of the geometric solids through foreshortening, even if he used several systems of perspective within the frame of a single painting. This feature detracts from the volition of the unlimited, free-floating weightlessness of Malevich's suprematist shapes, just as the three-dimensionality adds gravity, or at least body and volume, to Lissitzky's equally free-floating forms.[62]

Bois and Nisbet also emphasizes Lissitzky's mastery of materials; writing about Proun 2C, both notes the "very richly textured surface"[94] "wooden support sometimes appears as wood, and sometimes is treated to look like daub; in which glued pieces of paper or metal adopt all the characteristics of construction materials (the friable dullness of plaster, cement bubbles, the roughness of concrete, etc.)"[95] First Proun was painted on wood, later Lissitzky used both wood and canvas; some where done in tempera and not in oil. Birnholz sees it as continuation of "profound" Russian tradition, as "icons were painted in tempera on wood".[96]

Lissitzky used axonometric projections for Prouns, he believed that it is the best way to express infinity - "axonometry presented three-dimensional objects without perspectival foreshortening: parallel lines remained parallel, which allowed for a consistency of scale".[97]

Only small numbers of Prouns have been preserved, about 25 in total.[98]

In 1923 Lissitzky created a Proun Room, an installation for the Grosse Berliner Kunstausstellung. It was a small room, about 3 by 3 by 2.5 m that he transformed into a single work of art, that encouraged viewers to "walk into an image".[99] One of the main ideas behind the Room was making its visitors not just passive spectators, but active participants.[100][101] By working in real, "actual space", he surpassed Malevich, who also designed three-dimensional "architectons" few years before; Malevich designs were never done in real form and existed only on paper.[101] By working in real space he "fullfiled UNOVIS's longtime dream of suprematist space".[99] Forgács writes that by designing and constructing the Proun Room Lissitzky proved himself as one of the progressive artists of 1920s Berlin;[101] hovewer, he violated unwritten rule "to reject the commercialization of art and had put price tags on three three elements of the Proun Room". Price tags, together with Lissitzky's "half-dance" during the demonstration of the room to an audience, alienated his friend and colleague Theo van Doesburg.[102][103] Proun Room was recreated in 1965 in Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum by Jan Leering.[104][98]

Lissitzky was not the first artist working in real space; in 1920s a number of artists in Berlin experimented with such ideas and Lissitzky certainly knew it. Among those are Ivan Puni, who created a "personalized" environment for his works exhibiting in Der Sturm gallery in 1921; Wassily Kandinsky, whose designs were a part of Juryfreie Kunstschau (Jury-free exhibition) in 1922; and Erich Buchholz, who owned a well-known Berlin studio that he redesigned and turned into a "modernist artwork".[105][o] Nisbet sees the Proun Room to be a direct response to Kandinsky's installation.[106][p]

In 1923 Lissitzky published his Victory over the Sun figurines portfolio, called by Bois to be an "anthropomorphization of the Prouns".[95] The album was his rethinking of the 1920 UNOVIS design of that futuristic opera, probably inspired by Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and Rudolf Schwerdtfeger's "electrically operated color-light shows" in the Bauhaus.[107] Birnholz states that Lissitzky modeled the New Man figurine after the Leonardo's Vitruvian Man.[108] Nisbet notes that the idea behind the Vitruvian Man—"evocation of an ideal, transformed humanity"—is close to Lissitzky's vision of "utopian renewal of the world", and so the connection of two works is plausible.[109] Peter Larson rejects such comparison;[q] he thinks that Lissitzky drew himself in the portfolio: "the new technological-artistic man (Lissitzky himself, of course), as the plot of the opera reads, hurls the sun (the old cosmic source of energy) from the heavens and has himself become the star, the spark, the new self-sufficient source of creative impulse."[110] One of the figurines, the "Radio Announcer", was used before for illustrations of Mayakovsky book Dlia Golosa.[111]

Of Two Squares

[edit]

Little experimental book titled Pro 2 ■ (Pro 2 kvadrata: suprematicheskii skaz v 6i postroikakh (Of Two Squares: A Suprematist Tale in Six Constructions)) was created in 1920 in Vitebsk and published in 1922 in Berlin and then in De Stijl. It consists of 6 plates, and tells a story about two squares, red and black, travelling through space to Earth.[112] The book commands reader to participate, not just read it:[113]

don't read

take up

scraps of paper/little posts/blocks of wood

stack/paint/build

It tells the children to take part "in the construction of a better future augured by the red square's arrival". Lissitzky addresses the child (the reader) as "participant in the construction of the future".[113]

Forgács sees the "radical, suggestive, and futuristic contents" of the book as Lissitzky's manifestation as a "modernizer" versus Malevich, "whom, by contrast, he positioned—albeit with admiration and due respect—as archaic, a man of the past", and calls the book "an initiative to create the international visual language of the future." She also called the book "applied suprematism" and "a suprematist-communist cartoon", and gives interpretation of the plot:[112]

The plot is simple. The Red Square, a superior power, arrives from the cosmos in the company of the Black Square and triumphs over the old, disorderly, black-colored system on earth by disrupting, reconstructing, and recoloring it red. The Black Square, having witnessed the transformation of the chaotic black world into a clearly organized and regulated new red one, recedes back into the distance while the Red Square proceeds forward and directs its motion toward the viewer, covering the now red world, as if "stamping" it.[112]

Art historian Yve-Alain Bois suggested that it tells the story of the Revolution of 1917 – the black square being an anarchist movement that helped the red square (the communists) but soon was "driven out in a bloody purge by the Red Army during the events of Kronstadt in March 1921". He sees the book as a reference for a real history through anstract figures, and writes that "precisely because the scenario of this "story" is known in advance – a characteristic of the epic genre, where the emphasis on the codes is enhanced by a previous knowledge of the depicted facts – that Lissitzky is able to graft his ideological work onto the fundamentally abstract level of his semiological investigation".[95] Bois also wrote that the book can wrongly be seen as a comics, he instead writes that "another maneuver-a Trojan horse-suggests itself: the poster might become part of the book."[114]

Margolin compares the book with the Torah, because it "propagated an all-encompassing ideal ... the construction of a new world. The book's design combined the Jewish passion for moral improvement with Lissitzky's hope that art could play a prophetic role in bringing this about".[115] Samuel Johnson notes, however, that Lissitzky substituted messiah with "the interplanetary imagery of futurists poets like Velimir Khlebnikov".[59]

Photography

[edit]Lissitzky became first interested in photography in 1920s; in 1924 his future wife, Sophie Küppers, gave him her father's camera, "a monstrosity with wooden plate-holders measuring 13 x 18 cm. And a large Zeiss lens."[116] He soon created numerous photomontages, and started to promote fotopis, or "photo-painting".[117][118] His photomontages were described as done using "various darkroom techniques, often in unprecedented combinations, including double printing, sandwiched negatives, the use of photogram elements and the creation of multiple generations of prints."[119] However, modern analysis showed that Lissitzky used cheap, simple, and even "old-fashioned" techniques; for majority of his early works darkroom was not needed, and only after 1926 a real darkroom and an enlarger became necessary.[120] Klaus Pollmeier wrote that "He seems to have visualized many aspects of the final image before the exposure of the negative in the camera, compensating for the shortcomings of his limited technology with a sharp and almost boundless imagination."[120]

The first known photo work by Lissitzky was made together with the Dutch De Stijl artist Vilmos Huszar, published in Merz with a caption "El Huszar and Vilmos Lissitzky".[121] Among Lissitzky's photography works are a series of portraits of his friends and himself. He made a portrait of Kurt Schwitters, where he is photographed in front of the title page of Nasci journal issue; Hans Arp is portrayed in front of the Parisian Dada magazine of late 1920.[122] Lissitzky's famous self-portraits are called The Constructor and Self-Portrait with Wrapped Head and Compass.[123]

The Constructor

[edit]

The Constructor (Self-Portrait) is a photomontage created by Lissitzky in 1923-1924, when he was severely ill with tuberculosis and stayed in Swiss hospital (at this time he even considered a suicide).[124] It is a superimposed self-portrait and a photo of hand with a compass, with a graph paper extended to the left and right edges, with inverted letters and additional letters XYZ placed between the arrow and backwards L. Similar image of the hand with a compass was used earlier by Lissitzky for the Pelican advertisement. Two lines intersect in the upper left corner and touch all four edges. The Constructor became one of the most famous works of Lissitzky and of the whole constructivism movement.[26] Multiple versions of the collage exist.[26][120] The work was called "the icon of constructivist movement";[125] in 1965 designer Jan Tschichold called The Constructor Lissitzky's "finest and most important work".[124]

Researchers proposed several interpretations of the work. Nisbet writes that the usage of "the traditional iconography of the eye, the circle, and the pair of compasses" shows the author to be "the equivalent of the divine creator of the world", and compares the iconography of the hand on the photo with the hand from the Had Gadya illustrations.[123] Michel Frizot sees it as a "manifesto piece" that "glorifies human vision" compared with photocamera.[126] Rosalind Krauss compares Lissitzky's work with that of Herbert Bayer's (1937), and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy's to "establish the hand as an indexical signifier of 'new vision' in early 20th century photographs".[127][128]

Alla Vronskaya sees in The Constructor "a celebration of engineering and technology"; she also notes that compass was often used as a symbol of architecture. The eye and a compass were first used by Lissitzky in 1922, in a Tatlin at Work on the Monument to the Third International collage;[126][129] he also used them in the Pelican advertisement,[126] in the Vkhutemas bulletin, and in Film and Foto exhibition. This usage was connected with a standard Russian perspective textbook by Pavel Markov, Rules of linear perspective.[124] Lissitzky also created a second self-portrait, called Self-Portrait with Wrapped Head and Compass, where the author is not a measurer, but a measured object;[130] Lissitzky is facing left, his head covered with a white cap.[123]

In 1928 article, "The film of El's Life", Lissitzky described his eyes as "Lenses and eye-pieces, precision instruments and reflex cameras, cinematographs which magnify or hold split seconds, Roentgen and X, Y, Z rays have all combined to place in my forehead 20, 2,000, 200,000 very sharp, polished searching eyes".[131][132]

In a letter to Sophie from September 12, 1924, Lissitzky wrote "Am now working on a self-light-portrait [Selbstlichtportrait]. A colossal piece of nonsense, if it all goes according to plan."[133][134] In a later letter to Sophie he described it: "Enclosed is my self-portrait: my monkey-hand."[134] Paul Galvez called it the "great counteroffensive against reason", created after the rationalist Nasci journal.[134] Galvez compares The Constructor with earlier Pelican advertisement, he sees the former as an advertisement of artist's skill for sale:

As demonstrated by a comparison of the self-portrait with a particularly telling English-language Pelikan advertisement, the artist's skill is now an object up for sale. In this countertop ad, the artist's disembodied hand has now become the friendly handshake of your local salesman, complete with cuff links, white shirt, and plaid jacket. The central object is no longer Lissitzky's serious countenance but a bottle of waterproof drawing ink. The compass that once stood for the artist's skill can now only circumscribe the arc of the Pelikan logo...[134]

Kamczycki argues that Lissitzky was inspired by Chagall's works Homage to Apollinaire and Dedicated to Christ from 1912; he also connects the work with earlier Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, saying that both works have the "same layout". Homage to Apollinaire "depicts the scene of the mystical separation of Adam and Eve, placed against the background of a great clock with numbers 9, 0, 11. ... this clock ... can also be viewed as a great eye, also used in other works by Chagall. An intriguing element in this futuristic cubist work is the red wedge, schematically outlined but distinct". Dedicated to Christ "depicts a Passion scene captured in a cubist-futuristic painting formula." Both painting were linked to the Kabbalah book Paamon veRimon.[37] Kamczycki concludes, that

The motif of an incomplete circle containing a wedge in its outline, present in Lissitzky's art, is an illustrative, kabbalistic, cosmogonic metaphor for the process of creating the world through the act of "breaking up" or "cutting through". It is a desperate expression of loss of faith in the role of the artist, which contains almost imperceptible references to the sphere of kabbalistic mysticism.[37]

Record

[edit]

Record is a photomontage created by Lissitzky in 1926. Three versions of the print exist, Maria Gough describes it as "a lone and anonymous athlete on the verge of clearing a hurdle. His forward motion is guided by his outstretched left arm, the hand and fingers of which are almost amphibian in their streamlining. Intensely illuminated, his body, conspicuously unmarked by the trappings of any team or state, is substantial enough to cast an elongated, stainlike shadow across the track. Yet, at the same time, his physical density is draining away, merging into the electrified urban nightscape that surrounds him." The image of the athlete is superimposed with a photo of Broadway. She conludes that the collage "produces a double utopian fantasy: a human body powered by the electrical field in which it is embedded, and, at the same time, powering that very field through the conversion of its own thermal and kinetic energy into electricity." Another version of the same photocollage was cutted into 28 vertical strips to create an illusion of motion. Two or three negatives were used for the resulting image; photo of the Broadway was taken by an architect Knud Lonberg-Holm[119][117][120] in 1923 or 1924, he and Lissitzky met in Weimar. Lissitzky probably took the photo from Erich Mendelsohn's book Amerika: Bilderbuch eines Architekten (America: An architect's picture book). Later in an essay he wrote about "the great anonymous poetry of America — the verses and advertisements written in lights in the night sky of Chicago and New York".[117] The photo of the runner is taken from an unknown publication.[120]

Propaganda period

[edit]Architecture and teaching

[edit]After two years of intensive work Lissitzky was taken ill with acute pneumonia in October 1923. A few weeks later he was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis; in February 1924 he relocated to a Swiss sanatorium in Orselina, near Locarno. Here he got a surgery, "that left him with only half a lung".[135][136] While in sanatorium, he tried to translate some of Malevich's works and prepare them for publication. He struggled over this task because of Malevich's poor grammar and non-normative language.[137][r] Malevich was mostly unknown in Germany in the 1920s, and Lissitzky tried to compile his best articles to be presented to Western audience.[137][s] He tried to publish that book with several publishers, but was rejected by all; van Doesburg wrote a report for one of them, that, according to Forgács, "singlehandedly killed the publication project of Malevich's writings".[137]

During his stay in Orselina, Lisstzky read Malevich's article on Lenin, written soon after Lenin's death. The essay probably moved him to rework Ilya Chashnik's 1920 work, titled "Speaker's Tribune".[t] Lissitzky used Lenin's photo and changed the words used on Chashnik's work, resulting poster was called "The Lenin's Tribune".[138]

While staying in the tuberculosis sanatorium in Switzerland in 1924–25, Lissitzky completed the design of horizontal skyscrapers (Wolkenbügel, "cloud-hangers", "sky-hangers" or "sky-hooks"), an idea he had for more than two years. A series of eight such structures was intended to mark the major intersections of the Boulevard Ring in Moscow. Each Wolkenbügel was a flat three-story, 180-meter-wide L-shaped slab raised 50 meters above street level. It rested on three pylons, placed on three different street corners. One pylon extended underground, doubling as the staircase into a proposed subway station; two others provided shelter for ground-level tram stations.[139] Lissitzky argued that as long as humans cannot fly, moving horizontally is natural and moving vertically is not.[139]

In 1925, after the Swiss government denied to renew his visa, Lissitzky returned to Moscow and began teaching interior design and furniture design at the Wood and Metalwork faculty (Dermetfak) of the Vkhutemas (State Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops), a post he would keep until 1930. He all but stopped his Proun works and became increasingly active in architecture and propaganda designs. His works of that period were well-allied with Constructivism.[63] Besides the "utopian and impractical" Wolkenbügel project, he also worked on more ordinary buildings, designing interiors of communal housing blocks, Ginzburg and Milinis' House for the Employees of the Commissariat of Finance; he also worked with Vsevolod Meyerhold on a play design.[63] In 1928 he published his "The Artistic Pre-Requisites for the Standardisation of Furniture", where he stated his view on mass-produced objects.[140]

In 1926, Lissitzky joined Nikolai Ladovsky's Association of New Architects (ASNOVA) and designed the only issue of the association's journal Izvestiia ASNOVA (News of ASNOVA) in 1926.[141] The journal includes two articles: Ladovsky's "Skyscrapers of USSR and USA" and Lissitzky's article on Wolkenbügel. In ASNOVA Lissitzky also published a "proclamation" that architecture historian Alla Vronskaya described as "Lissitzky's antianthropocentrism":[141]

MAN IS THE MEASURE OF ALL TAILORS

[Our] great-grandmothers believed that the Earth is the center of the world,

And man is the measure of all things.

[They] said about these objects: "What a mighty giant!"

And this even now is compared with nothing else but a fossilized animal

Compare this neither with bones, nor with meat,

Learn to see that which is in front of your eyes,

Directions for use: Throw [your] head back, lift the paper, and then you will see

Here is the person, the measure of the tailor,

But measure architecture with architecture.

After some time of creating "paper architecture" projects Lissitzky was hired to design a printing plant of Ogonyok magazine in Moscow in 1927; it is Lissitzky's sole tangible work of architecture.[142]

Exhibition design

[edit]

In 1926, Lissitzky left the country again, this time for a brief stay in the Netherlands with Mart and Leni Stam in Rotterdam; he also visited Cornelis van Eesteren and J.J.P. Oud.[143] There he designed a temporary exhibition room for the Internationale Kunstausstellung art show in Dresden, the Raumes für konstruktive Kunst ('Room for Constructivist Art'), and a permanent exhibition Kabinett der Abstrakten ('Abstract Cabinet') for the Hanover's Provinzialmuseum.[144][63] It presented the works of Piet Mondrian, László Moholy-Nagy, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Mies van der Rohe, Kurt Schwitters, Alexander Archipenko, and others.[145] In his autobiography (written in June 1941, and later edited and released by his wife), Lissitzky wrote, "1926. My most important work as an artist begins: the creation of exhibitions."[146]

Lissitzky wrote about museum exhibitions as of 'zoos':[145]

Large international art shows resemble a zoo where the visitors are subjected to the roar of thousands of assorted beasts. My space will be designed in such a way that the objects will not assault the visitor all at once. While passing along the picture-studded walls of the conventional art exhibition setup, the viewer is lulled into a numb state of passivity. It is our intention to make man active by means of design. This is the purpose of space.

Kabinett was destroyed in 1937 by the Nazis, its contents were showed later in Munich in a "degenerate art" (Entertete Kunst) exhibition.[147] Though the Nazi party detested the avant-garde art and called Bauhaus an "alien" and "Jewish" "Spartacist-Bolshevik institute", and that their "artistry [was that] of the mentally ill", the design of early Nazi propaganda was described to be "done in the Lissitzky-Rodchenko-Klutsis style".[148] Scholars have traced Lissitzky's ideas in fascist and nazist exhibitions of 1930s.[149][150][151]

In 1927, Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Head of Narkompros, appointed Lissitzky as a supervisor of the Soviet pavilion for the Pressa exhibition in Cologne, scheduled for May 1928. Lissitzky became a head of "38-member 'collective of creators'",[146][151] with Sergei Senkin and Gustav Klutsis among them (they were not credited for the exhibition).[152][153] They produced 227 exhibits, most of them in Moscow.[151] The centerpiece of the pavilion was 3.8-meter-high, 23.5-meter-long photofresco[154] called "The Task of the Press is the Education of the Masses".[151][146][155] It depicted the history and importance of the press in the Soviet Russia after the Revolution, and its role in education of the masses.[151] It was compared to theater and cinema, with one reviewer describing it as "a drama that unfolded in time and space. One went through expositions, climaxes, retardations, and finales."[151][155] Instead of building their own pavilion, the Soviets rented the existing central pavilion, the largest building on the fairground. In his design, Lissitzky treated viewers as actors, who can interact with the exhibition.[156] In the center of the pavillion was a "giant" red star, electrified with neon lights;[157][70] above the star was a communist slogan, "Workers of the world, unite!".[70] The pavillion boasted that the USSR had 212 newspapers in 48 languages.[158] Lissitzky received a governmental medal for the design of the pavillion.[151]

Berliner Tageblatt on 26 May 1928[70] wrote about the exhibition, contrasting British and Soviet pavilions:[156]

What a contrast can be seen between the British and Soviet wings! ... As for Russia, we have to recognise the grandeur in the exhibition of social conditions, with truly mechanised equipment, conveyor belts forming large, Cubist-style zigzags, unnerving with the great steps they take in the name of progress, which are presented in a bold, brash manner, always in a dazzling red. Forwards! Towards the struggle and class-consciousness![156]

Lissitzky also designed several other exhibitions, including All-Union Polygraphic Exhibit (Moscow, 1927), "Film and Photography" (Stuttgart, 1929), the International Fur Trade Exhibition (Leipzig, 1930)[u] and the International Hygiene Exhibition[v] (Dresden, 1930).[63][153]

Later years

[edit]

In 1932, Joseph Stalin closed down independent artists' unions; former avant-garde artists had to adapt to the new climate or risk being officially criticised or even blacklisted. Lissitzky retained his reputation as the master of exhibition art and management into the late 1930s. His tuberculosis gradually reduced his physical abilities, and he was becoming more and more dependent on his wife, Sophie, in his work.[159][160][153] Margarita Tupitsyn writes that though Lissitzky was severely ill, multiple commissions were benefitial for him, because the government-sponsored work gave Lissitzky stable income and allow him to be treated in state sanatoriums.[161][153]

Art historian Peter Nisbet sees that transition from individual work to Stalinist propaganda as an insult to the artist: "the Prometheus of Proun is transformed into a Stalinist Sisyphus".[162] Margolin credited Lissitzky for creation of the Social Realist style;[163] about his transition to propaganda he writes: "In the face of imminent danger Lissitzky's and Rodchenko's struggle for utopia became instead striving for survival, and modest acts of resistance in an imperfect world became an acceptable end."[164][163]

In 1937, Lissitzky served as the lead decorator for the upcoming All-Union Agricultural Exhibition (Vsesoyuznaya Selskokhozyaistvennaya Vystavka), reporting to the master planner Vyacheslav Oltarzhevsky but largely independent and highly critical of him. The project was delayed after the arrest of Oltarzhevsky. Later, Lissitzky agreed to design only the central pavillion; his designs were criticesed for being "primitive" and "schematic". In 1938 Lissitzky's project was rejected.[165]

In 1932-1940 Lissitzky together with his wife worked on the USSR in Construction propaganda magazine, that was published in English, German, French, Russian, and, later, Spanish. It was done mainly for foreign audience to create a "favorable image" of the USSR. Lissitzky was not the only avant-garde artist who worked on the magazine, another one was Alexander Rodchenko.[166] Lissitzky worked on multiple issues, including "Four Bolshevik Victories" (1934, no. 2), "The 15th Anniversary of Soviet Georgia" (1936, no. 4-5),[167] and "Arctica",[166] "Fifteen Years of the Red Army", "Dneprostroy", "Polar Ship Chelyuskin", "The Korobov Family" (with Isaac Babel as writer), "Kaberdino-Balkaria", "The Soviet Fleet", and "The Far East".[160]

In 1941, Lissitzky's tuberculosis worsened, but he continued to work; one of his last pieces was a propaganda poster for USSR's efforts in World War II, titled "Davaite pobolshe tankov!" ("Give us more tanks!" or "Produce more tanks!").[164] He died on 30 December 1941, in Moscow.[168]

Family

[edit]

Lissitzky maintained a good relationship with his family. In 1925 his sister Jenta committed a suicide in Vitebsk, while he was in a hospital in Switzerland.[169][170] Sophie wrote that she "had been closest to him of all his family".[169] After his return from Germany in 1925, Lissitzky met his father and brother Ruvim:

The following morning my father and brother came to meet me at the station in Moscow and took me by another train directly to the dacha. They both look well. My father is still very active and well preserved for his age. My brother is a big fellow and a tovarishch of the best order. They had expected to meet a 'living corpse' and were apparently very surprised to see a big fat pig. The dacha is a little house in a country village, fifteen kilometres from Moscow, three kilometres from the railway station. The air here is doing me a lot of good. My brother's wife is kindness itself, a girl of your build, only taller and correspondingly broader than you are.[171]

Lissitzky and Sophie Küppers married at 27 January 1927 in Moscow; she left her two sons in a boarding school in Germany, planning to take them on holidays to USSR.[172] According to their grandson, the families of both Lissitzky and Sophie opposed their decision to marry.[173] Their son Jen was born in Moscow in 12 October 1930,[174] named after Lissitzky's sister, Jenta.[173] To celebrate his son's birth Lissitzky created a photomontage now usually called Birth Announcement of the Artist's Son. Perloff describes it as "A poignant and enigmatic image [...] the infant Jen is superimposed upon photographs of a smiling female worker, a smoking factory chimney and whistle, and a newspaper celebrating Stalin's First Five-Year Plan". This work is considered a personal endorsement of the Soviet Union, as it symbolically links Jen's future with his country's industrial progress.[175]

After Lissitzky's death from tuberculosis in 1941, Sophie and Jen were sent into exile to Novosibirsk as German nationals. Sophie's son Hans was arrested and put into a labor camp. They lived in a barrack; Sophie first worked as a cleaning worker but soon was able to sew and knit.[173] Jen later changed his name to Boris; when he was 17, he received a passport with the ethnicity stated as "Russian". He brought El Lissitzky's archives from Moscow to Sophie. Jen became a photographer himself, working for Novosibirsk newspapers.[176] Sophie's exile was "officially ended" in 1956, but she stayed in Novosibirsk.[80] In 1960s she wrote a book in German about El Lissitzky, because it was impossible to publish such book in USSR as it contained a nearly-banned names of Lissitzky, Malevich, Filonov, Tatlin, Klucis and others.[176]

Views

[edit]Typography and books

[edit]1. The words on the printed sheet are learnt in by sight, not by hearing.

2. Ideas are communicated through conventional words; the idea should be given form through the letters.

3. Economy of expression – optics instead of phonetics.

4. The designing of the book-space through the material of the type, according to the laws of typographical mechanics, must correspond to the strains and stresses of the content.

5. The design of the book-space through the material of the illustrative process blocks, which gives reality to the new optics. The supernaturalistic reality of the perfected eye.

6. The continuous page-sequence – the bioscopic book.

7. The new book demands the new writer. Ink-stand and goose-quill are dead.

8. The printed sheet transcends space and time. The printed sheet, the infinity of the book, must be transcended.

THE ELECTRO-LIBRARY.

Lissitzky worked with numerous printed forms, including scrolls, codexes, pamphlets, portfolios, newspapers and posters. He started as a children's book designer and illustrator, but soon started to create avant-gardist books.[177] Book design and typography remained important for him during all his life. He called it an "architecture of the book", and wrote in length about importance of books. Nisbet notes that Lissitzky deemed three aspects of books to be important: "that it is educational, that it is mobile, and that it is infinitely reproducible."[178] In 1919 article "The New Culture" Lissitzky wrote:[179][49]

But surely the book is now everything. In our time it has become what the cathedral with its frescoes and stained glass (colored windows) used to be, what the palaces and museums, where people went to look and learn, used to be. The book has become the monument of the present. But in contrast to the old monumental art, it itself goes to the people and does not stand like a cathedral in one place, waiting for someone to approach.

The book now expects the contemporary artist to use it so as to make this monument of the future.[49]

Kamczycki connects Lissitzky's occupation with book design with Jewish traditions:

in Jewish tradition, the idea that letters are building blocks of the universe is found in the first century CE when Rabbi Akiva interpreted the shape of the letters as indicative of certain kinds of powers and was concerned with their transmutational possibilities. There is a remarkable similarity between Akiva's observation and a key statement by Lissitzky concerning the infinity of the text. As Lissitzky himself wrote: "The letter is an element which is itself composed of elements".[180]

Lissitzky also wrote about Jewish traditions, for example in his 1923 article On Mogilev shul:[181]

Every synagogue always had a small library. The cases hold some of the oldest editions of the Talmud and other religious texts, each with frontispieces, decorative devices and tailpieces. These few pages fulfilled the same function in their time as illustrated journals do in our own day: they familiarised everyone with the art trends of the period.

In 1923 Lissitzky published his article Topography of Typography. Despite his thesis that "The words on the printed sheet are learnt in by sight, not by hearing", he dedicated a lot of work designing Mayakovsky's poetry book For the Voice, published in Berlin in the same year.[182] In that book he called himself the "constructor of the book";[114] the book itself contained a thumb index.[183][184] Lissitzky later wrote: "My pages stand in much the same relationship to the poems as an accompanying piano to a violin. Just as the poet in his poem united concept and sound, I have tried to create an equivalent unity using the poem and typography".[182][114] Topography of Typography was not his first theoretical work about books; in 1920 he wrote in the first issue of the UNOVIS almanach: "Gutenberg's Bible was printed with letters only; but the Bible of our time cannot be just presented in letters alone."[114][185] Later Lissitzky wrote about children's books: "By reading, our children are already acquiring a new plastic language; they are growing up with a different relationship to the world and to space, to shape and to colour; they will surely also create another book."[186]

Science, mathematics, and art

[edit]

Lissitzky, an architect, was always interested in interconnections between scientific theories and art. He became interested in Malevich's Suprematism; John G. Hatch writes that it was based on thermodynamics, "describing the coloured forms of Suprematism as representing nodes or concentrations of energy, and its whole narrative as one paralleling the universe's evolution toward thermal death, as postulated by the second law of thermodynamics". Malevich was also interested in theosophy and philosophy, which was of no interest for Lissitzky. Prouns were an attempt to create a new form of Suprematism, and he tried to integrate new scientific theories into it. One of the earliest examples is Proun G7, based on Hermann Minkowski's diagram from the "Space and Time" essay; "It not only incorporates the hyperbolas found in Minkowski's diagram, it transcribes the oblique presentation of the x- and y-axes as well." Several other works are also similar to that diagram.[188]

Though most researchers agree that mathematics plays important role in Lissitzky's thought, Richard J. Difford doubts that Lissitzky directly referenced mathematical papers.[189] Lissitzky thought about himself as of "artist-engineer" contrasting it to the "artist-priest" tradition of Malevich. In 1922 he gave a lecture called "New Russian Art" in Berlin, where he stated that "The idea that art is religion and the artist the priest of this religion we rejected forthwith."[27]

While in Berlin, Lissitzky was influenced by the ideas of philosopher-biologist Raoul Heinrich Francé, who was a director of the Biological Institute of the German Mycological Society in Munich,[187] especially by his "biotechnics",[190] "an idea that called for humans to learn new principles and processes from the dynamic powers of nature that would recalibrate human society to the animal world".[187] Nisbet have found multiple allusions to Francé in Lissitzky's works, most notably in August 1924 issue of the journal Merz, published together with Kurt Schwitters, titled Nasci.[190] Lissitzky and Schwitters wrote on the cover: "'Nature', from the Latin term NASCI, signifies becoming, origination, that is to say, what develops, forms and moves itself from its own proper force."[187] Forgács calls the issue a "programmatic homage to nature as opposed to artificiality, including the concept he had once shared with van Doesburg: that art is superior to nature". The last page of the journal has a heading that reads: "Enough of the MACHINE MACHINE MACHINE with which man has achieved modern artistic production".[191] Nisbet notes Nasci's "organic orientation" and several quotes from Francé's books; the last page of the issue featured photography of the planet Mars, similar to one from Francé's 1923 book. Lissitzky used photo of Mars even earlier, in his 1920 article "Suprematism of Creativity" in the Unovis Almanac. In the essay Lissitzky stated: "Here are signs of Earth and Mars. The savage does not understand the content of the first. We do not understand the content of the other."[190]

Lissitzky's article "A. and Pangeometry" was published in avant-garde magazine Europa Almanach in 1925 (in German), edited by Carl Einstein and Paul Westheim.[192] The article was a tribute to Nikolai Lobachevsky's essay, "Pangeometry", of 1855, one of the first works on non-Euclidian geometry.[188][193][194] Lissitzky, an architect by education, was one of a small number of avant-garde artists who can understand modern science and mathematics; in his Prouns and articles he was interested in concepts of infinity and relativity. Igor Dukhan writes that "Lissitzky's imagination was stimulated by the ideas of space revealed by non-Euclidean geometry and the theory of relativity. He was attracted by the irrational worlds discovered by the latest mathematics and natural sciences, which could not always be represented by spatial, geometrical or numerical means—conceptual worlds of 'immaterial materiality' (Lissitzky's phrase)."[192]

Dukhan places the article into "historical context of Jewish messianic ideas":[10]

As early as the third century CE, the program of the Dura Europos frescoes was marked by the pronounced dominance of the forthcoming messianic future overother horizons of time – an ancient Jewish utopian time project. [...] In Lissitzky's case, it is essential just to mention that the apocalyptical thinking of the Russian revolutionary era was washed by the waves of the Jewish messianic mentality. The latter makes Lissitzky's montage of time in "Art and Pangeometry" understandable, and his specific visualization and sensibility of the future's domination over "here and now".[10]

Esther Levinger notes "mathematical precision" of Lissitzky's works, which she called his "art-games"; Lissitzky himself wrote about mathematics as a game: "Archimedes would have regarded modern mathematics as a clever, but curious GAME (because its aim is not an end result like three buns, forty five kopecks, etc ... but the actual operation, combination and construction of dependences which we find with Gauss, Riemann and Einstein)." For Lissitzky, both art and mathematics is a game, both activities are "rule-bound". Levinger draws parallels between Lissitzky's ideas (analogies between art and game), and Wittgenstein's (analogies between language and game).[195][196][w]

Manuel Corrada analysed mathematical ideas that Lissitzky described in his essay; he found that Lissitzky's explanations "can be easily expressed in mathematical terms". Corrada concludes: "Proun Space was Lissitzky's visualization of a four-dimensional manifold-in his own words, the creation of 'imaginary space'. ... his method of visualizing abstract mathematical notions was coherent, even if from these works alone it seems impossible to comprehend the mathematical concepts involved."[197] Lissitzky's use of axonometry for Prouns was described as "a way by which we may apprehend infinity".[189]

Bauhaus

[edit]UNOVIS, Vkhutemas, and Lissitzky as individual artist are often compared with and even called a "Russian Bauhaus".[198][199] Lissitzky lived in Berlin in the early 1920s and was aware of the Bauhaus school and works through his friends and colleagues; in 1923 he was introduced to Walter Gropius and later visited Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar.[200] Still, his views on the movement were not favourable. He wrote in a letter to Sophie in 1923:

The criminals in Russia were formerly branded on the back with a red diamond and deported to Siberia. In addition, they had half their hair shaved off their heads. Here in Weimar, the Bauhaus puts its stamp – the red square – on everything, front and back. I believe the people have also shaved their heads...[201]

In 1927 Lissitzky even proclaimed that Bauhaus was inspired by Vkhutemas, though it did not exist when the Bauhaus school was founded.[202]

Scholarly assessment and legacy

[edit]

Several art historians wrote in length about Lissitzky's legacy.

Peter Nisbet writes of Lissitzky as of one who have "most diverse and extensive career":

El Lissitzky had one of the most diverse and extensive careers in the history of twentieth century art. A bare outline of his activities can give only some indication of this wide-ranging multifariousness: Lissitzky the architecture student in Germany before the Great War; Lissitzky the participant in the revival of Jewish culture in Russia around the time of 1917 revolutions; Lissitzky the passionate convert to geometrical abstraction and coiner of the neologistic title "Proun" for his paintings, prints and drawings; Lissitzky the participant in the cultural debates on the social and political role of creativity; Lissitzky in Germany in the 1920s as a bridge between Soviet and Western European avant-gardes; Lissitzky the prolific essayist, journal editor, lecturer and theorist; Lissitzky as a founder of modern graphic design; Lissitzky the experimenter with photographic techniques; Lissitzky as architect of visionary skyscrapers, temporary trade fairs, and industrial buildings for the Soviet Union; Lissitzky in Russia in the 1930s as loyal propagandist of the achievements of socialism under Stalin.[204]

Yve-Alain Bois agrees with Nisbet, writing that there is not one, but three Lissitzkys,[x] Dukhan also writes about Lissitzky as an artist "between" the styles.[y] This view is challenged by some scholars - Maria Mileeva sees this distinction of different Lissitzkys misleading.[70]

Lissitzky's works inspired many artists. In 1920s, Polina Khentova, Lissitzky's good friend from his early days in Moscow, created embroidery and several illustrations using his drawings as inspiration.[203] In 1982, American artist Frank Stella created his version of Had Gadya after seeing Lissitzky's book of the same name in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.[205][206]

First post-war exhibition of Lissitzky in the USSR was in the 1960 at the Mayakovsky Museum. The exhibition was created by Nikolai Khardzhiev and became possible only by linking Lissitzky to Mayakovsky, who was a "recognized" Soviet poet. The next exhibition followed only in 1990s.[70] Lissitzky's works are now exhibited in many major museums, including Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow),[207][208] Vitebsk Center of Contemporary Art,[209] MoMA (New York),[210] Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven),[211] Stedelijk (Amsterdam)[212] and others.

Abstract Cabinet was recreated in 1969 in Sprengel Museum, Hannover.[213] In 2017 it was recreated in augmented reality.[214] Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven has one of the biggest collection of Lissitzky's works. Proun Room was recreated there in 1965, Abstract Cabinet was partially recreated in 1990. For the "Lissitzky+" exhibition four models based on figurines from Victory over the Sun were made: the "Announcer", the "Time Traveler", the "Gravediggers" and the "New Man". Eight-metre-high statue of the "Gravediggers" was installed in the pond of the museum.[98]

"El Lissitzky – Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. Utopia and Reality" was an exibition of Van Abbe Museum, set as a "dialogue" between Lissitzky and Ilya Kabakov.[215][216] Kabakov was ...[217]

Notes