User:Ajglove1/Psychological horror

The Psychology behind the Fascination with Psychological Horror movies

Psychological horror films evoke diverse emotions in viewers, influencing their preferences toward or against such cinematic experiences. Enjoyment of these films is not universal; some find them unpleasant or even repulsive. Factors such as personality traits, sensation-seeking tendencies, empathy levels, and a need for affect contribute to individuals' responses to psychological horror movies. Notably, certain dark personality traits—Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism—are associated with a proclivity for enjoying these films.[1]

The allure of psychological horror movies lies in elements such as suspense, tension, and resolution, all of which contribute to the arousal experienced by viewers. Despite often featuring open-ended conclusions, these films do not diminish the overall enjoyment. Employing suspense, tension, mind games, and manipulation, psychological horror movies induce fear in audiences. The physiological response to fear, commonly known as the fight-or-flight [2]reaction, triggers an instinctive survival response shaped by evolution. This response involves the autonomic nervous system, with the sympathetic system initiating the fight-or-flight reaction and releasing dopamine and endorphins that block pain and induce pleasure.

The viewing experience of psychological horror movies provides a simulated sense of danger, resulting in a false high and a feeling of accomplishment upon overcoming fear. Such films allow individuals to explore taboo desires in a controlled setting, aligning with insights from the perspective of Hauke[3]. However, excessive exposure to these films may lead to negative mental and physical effects. Desensitization, wherein the shock factor diminishes, can occur, and prolonged exposure may contribute to increased anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and elevated heart rates, posing risks to those with underlying heart conditions. Despite potential drawbacks, psychological horror movies leave a lasting impact, fostering a state of arousal and provoking contemplation. Well-crafted examples, such as "Us," [4]prompt prolonged reflection by utilizing the unknown and fear to challenge viewers' thinking processes both during and after the viewing experience.

A research initiative involving college students aimed to develop a comprehensive scale for evaluating cognitive responses to frightening movies. The resulting instrument, known as the EFF (Emotion, Fear, and Fright) scale, demonstrated both reliability and validity, as confirmed by the success of studies 1 and 2.[5] The scale, comprising ten items, enabled participants to self-assess the impact of the films on their psychological experiences.

However, a noteworthy omission in the experimental design was the consideration of environmental or contextual factors during the film-viewing experience. It is recognized that the context in which individuals watch these movies can significantly alter their psychological responses. This oversight highlights the importance of acknowledging the influence of viewing conditions on the observed effects of frightening films.

Hauke, in his discussion on the psychological aspects of horror films, explores the profound appeal they hold for audiences, suggesting that they provide a means for viewers to transcend their everyday reality. This perspective adds to the broader understanding of why individuals are drawn to horror films, viewing them as a form of escapism—a temporary disconnection from the mundane. The experience of watching such films can elevate one's thought processes, challenging conventional notions of rationality.

Taking the movie "Triangle"[6] as an example, Hauke highlights its capacity to provoke contemplation on the boundaries of reality. The narrative of "Triangle" evoked parallels with another film, "Fall,"[7] which similarly incorporates a significant psychological twist, leaving audiences in a state of shock and awe. Hauke encapsulates this phenomenon by stating, "this is where the horror starts and the rationality ends." Both "Triangle" and "Fall" share a commonality in their ability to subvert perceptions of reality, introducing sinister elements that disrupt the expected narrative trajectory.

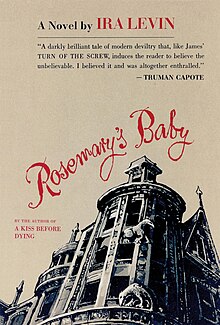

Rob Davies[8] authored a comprehensive article delving into the techniques employed by Roman Polanski to depict the profound paranoia experienced by the heroines in his films. Notably, in "Rosemary's Baby"[9] and "Repulsion,"[10] the protagonists undergo continuous turmoil and stress, with Polanski employing psychological triggers that resonate with women on a relatable level. The director achieves this by placing the protagonists in eerie, unfamiliar environments, creating internal monsters, and blurring the lines between reality and illusion, employing surrealistic elements. In "Repulsion," the character Carol grapples with anxiety and schizophrenic tendencies, including hearing voices, while Rosemary in "Rosemary's Baby" is subjected to a traumatic event and struggles to distinguish whether it was perpetrated by her husband or a supernatural entity, ultimately accepting it. Both films explore themes of psychological repression stemming from societal expectations, religious influences, and sexual deviancy, resulting in a significant psychological toll on the characters. However, in the end, they are portrayed as victorious and justified, highlighting the effectiveness of blending reality and fantasy in enhancing the impact of psychological horror on viewers.

The incorporation of psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and neurodevelopmental disorders[11] in horror films has been a prevalent theme for decades, with a notable shift in recent times toward portraying characters with mental disorders in a more nuanced light.[12] Earlier films, including "The Shining,"[13] "Psycho,"[14] and "Halloween,"[15] often depicted characters with mental disorders as dangerous psychopaths, contributing to the negative stigma associated with mental illnesses. Contemporary films, such as "Split"[16] and "Pearl,"[17] strive to present these characters with more understanding and elicit moments of compassion from the audience, although the overarching theme of their potential danger and mental illness remains. The use of real scenarios and mental health conditions enhances the realism of these portrayals, thereby intensifying the impact on viewers and heightening the fear factor.

A study was conducted to see if movie genres influenced psychological resilience during the pandemic. Through rigorous testing with groups, they were able to determine that preferring horror movies and fiction helped people with the psychological toll of enduring COVID. The Pandemic Psychological Resilience Scale,[18] or PPRS, was created to assess psychological resilience during the pandemic. The study determined that being a horror fan didn’t increase positive resilience, but it did show that they had lower psychological distress. A possibility from this study is that through ongoing exposure to horror in a safe space, we develop a better handle on our emotions during stressful situations. Almost like exposure therapy, we put our bodies regularly through that stress from fear, so much so that it adapts. In this light, psychological horror films are acknowledged to have some positive psychological benefits for viewers.

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

[edit]Lead

[edit]Article body

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Martin, G. Neil (2019-10-18). "(Why) Do You Like Scary Movies? A Review of the Empirical Research on Psychological Responses to Horror Films". Frontiers in Psychology. 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02298. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6813198. PMID 31681095.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Why Do People Like Horror Movies? What Is the Psychology Behind It? - Psi Chi, The International Honor Society in Psychology". www.psichi.org. Retrieved 2023-11-10.

- ^ Hauke, Christopher (2015-11). "Horror films and the attack on rationality". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 60 (5): 736–740. doi:10.1111/1468-5922.12181. ISSN 0021-8774.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Us (2019 film)", Wikipedia, 2023-10-13, retrieved 2023-10-21

- ^ Sparks, Glenn G. (1986-01). "Developing a scale to assess cognitive responses to frightening films". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 30 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1080/08838158609386608. ISSN 0883-8151.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Triangle (2009 British film)", Wikipedia, 2023-10-03, retrieved 2023-11-25

- ^ "Fall (2022 film)", Wikipedia, 2023-11-11, retrieved 2023-11-25

- ^ Davies, Rob (2014-06-01). "Female Paranoia: The Psychological Horror of Roman Polanski". Film Matters. 5 (2): 18–23. doi:10.1386/fm.5.2.18_1. ISSN 2042-1869.

- ^ "Rosemary's Baby (film)", Wikipedia, 2023-10-31, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ "Repulsion (film)", Wikipedia, 2023-10-31, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ "Mental disorders". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ Mancine, Ryley (2020-09-10). "Horror Movies and Mental Health Conditions Through the Ages". American Journal of Psychiatry Residents' Journal. 16 (1): 17–17. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2020.160110. ISSN 2474-4662.

- ^ "The Shining (film)", Wikipedia, 2023-11-10, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ "Psycho (1960 film)", Wikipedia, 2023-11-04, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ "Halloween (franchise)", Wikipedia, 2023-11-09, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ "Split (2016 American film)", Wikipedia, 2023-10-31, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ "Pearl (2022 film)", Wikipedia, 2023-11-04, retrieved 2023-11-10

- ^ Scrivner, Coltan; Johnson, John A.; Kjeldgaard-Christiansen, Jens; Clasen, Mathias (2021-01). "Pandemic practice: Horror fans and morbidly curious individuals are more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic". Personality and Individual Differences. 168: 110397. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110397. PMC 7492010. PMID 32952249.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link)