University of Reading

| ||||||||||||||||

Former name | University College, Reading | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Public | |||||||||||||||

| Established | 1892 – University College, Reading 1926 – university status | |||||||||||||||

| Endowment | £111.4 million (2024)[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Budget | £339.2 million (2023/24)[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Paul Lindley[2] | |||||||||||||||

| Vice-Chancellor | Robert Van de Noort[3] | |||||||||||||||

Academic staff | 1,610 (2022/23)[4] | |||||||||||||||

Administrative staff | 2,225 (2022/23)[4] | |||||||||||||||

| Students | 19,485 (2022/23)[5] | |||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 12,725 (2022/23)[5] | |||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 6,760 (2022/23)[5] | |||||||||||||||

| Location | , , 51°26′31″N 0°56′44″W / 51.44194°N 0.94556°W | |||||||||||||||

| Colours | Black, white and purple[6] | |||||||||||||||

| Affiliations | ||||||||||||||||

| Website | reading | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

The University of Reading is a public research university in Reading, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1892 as the University Extension College, Reading, an extension college of Christchurch College, Oxford, and became University College, Reading in 1902.[7] The institution became a university with the power to grant its own degrees in 1926 by royal charter from King George V, and was the only university to receive such a charter between the two world wars. The university is usually categorised as a red brick university, reflecting its original foundation in the 19th century.[8]

Reading has four major campuses. In the United Kingdom, the campuses on London Road and Whiteknights are based in the town of Reading itself, and Greenlands is based on the banks of the River Thames in Buckinghamshire. It also has a campus in Iskandar Puteri, Malaysia. The university has been arranged into 16 academic schools since 2016. The annual income of the institution for 2023–24 was £339.2 million of which £33.7 million was from research grants and contracts, with an expenditure of £257.2 million.[1]

History

[edit]

University College, Reading

[edit]The university owes its first origins to the Schools of Art and Science established in Reading in 1860 and 1870. In 1892, the College at Reading was founded as an extension college by Christ Church, a college of the University of Oxford. It opened in September of that year under the name of The University Extension College in Conjunction with the Schools of Science and Art, Reading, which was soon shortened the following spring to The University Extension College, Reading.[9] The first president was the geographer Sir Halford John Mackinder, and the college's first home was the old hospitium building behind Reading Town Hall. The Schools of Art and Science were transferred to the new college by Reading Town Council in 1892.[10][11][12][13]

The new college was incorporated in 1896 and was approved to participate in the Parliamentary grant to university colleges by the Commissioners of the Treasury in 1901, resulting in it changing its name to University College, Reading in 1902.[9] Three years later it was given a site, now the university's London Road Campus, by the Palmer family (connected with the firm of Huntley & Palmers). The same family supported the opening of Wantage Hall in 1908 and of the Research Institute in Dairying in 1912.[10]

University status

[edit]The college first applied for a royal charter in 1920 but was unsuccessful at that time. However a second petition, in 1925, was successful, and the charter was officially granted on 17 March 1926. With the charter, the college became the University of Reading, the only new university to be created in the United Kingdom between the two world wars.[10] It was added to the Combined English Universities constituency in 1928 in time for the 1929 general election.[citation needed]

In 1947, the university purchased Whiteknights Park, which was to become its principal campus. In 1984, the university started a merger with Bulmershe College of Higher Education, which was completed in 1989.[10][14][15]

2006–present

[edit]In October 2006, the Senior Management Board proposed[16] the closure of its Physics Department to future undergraduate application. This was ascribed to financial reasons and lack of alternative ideas and caused considerable controversy, not least a debate in Parliament[17] over the closure which prompted heated discussion of higher education issues in general.[18] On 10 October, the Senate voted to close the Department of Physics, a move confirmed by the council on 20 November.[19] Other departments closed in recent years include Music, Sociology, Geology, and Mechanical Engineering. The university council decided in March 2009 to close the School of Health and Social Care, a school whose courses have consistently been oversubscribed.[20][21]

In January 2008, the university announced its merger with the Henley Management College to create the university's new Henley Business School, bringing together Henley College's expertise in MBAs with the university's existing Business School and ICMA Centre. The merger took formal effect on 1 August 2008, with the new business school split across the university's existing Whiteknights Campus and its new Greenlands Campus that formerly housed Henley Management College.[22][23]

A restructuring of the university was announced in September 2009, which would bring together all the academic schools into three faculties, these being the Faculty of Science, the Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social sciences, and Henley Business School. The move was predicted to result in the loss of some jobs, especially in the film, theatre and television department, which has since moved into a brand new £11.5 million building on Whiteknights Campus.[24]

In late 2009 it was announced that the London Road Campus was to undergo a £30 million renovation, preparatory to becoming the new home of the university's Institute of Education. The Institute moved to its new home in January 2012.[25] The refurbishment was partially funded by the sale of the adjoining site of Mansfield Hall, a former hall of residence, for demolition and replacement by private sector student accommodation.[26]

The university is a lead sponsor of UTC Reading, a new university technical college which opened in September 2013.[27][28]

In 2016, a move to reorganise the structure of Reading University provoked student protests.[29] On 21 March 2016, staff announced a vote of no confidence in the vice chancellor Sir David Bell.[30] Eighty-eight per cent of those who voted backed the no confidence motion.[31]

In 2019, The Guardian reported the university was in "a financial and governance crisis" after recently reporting itself to regulators over a £121 million loan. The university is sole trustee of the charitable National Institute for Research in Dairying trust, and after selling trust land had then borrowed the £121 million proceeds from the trust, despite the potential conflict of interest in the decision making. Including this loan, the university has debts of £300 million, as well as having an operating deficit of over £40 million for the past two years.[32][33]

In 2021, the university declared, in a statement reply to the student's union, that it would not refund tuition fees for its students.[34]

Campuses

[edit]

The university maintains over 1.6 square kilometres (395 acres) of grounds, in four distinct campuses:

Whiteknights

[edit]Whiteknights Campus, at 1.3 square kilometres (321 acres),[35] is the largest and includes Whiteknights Lake, conservation meadows and woodlands as well as most of the university's departments. Though within the Reading urban area, most of the campus actually falls within Wokingham District (parish of Earley). The campus takes its name from the nickname of the 13th century knight John De Erleigh IV or the 'White Knight', and was landscaped in the 18th century by the Marquis of Blandford. The main university library, in the middle of the campus, holds nearly a million books and subscribes to around 4,000 periodicals. The URS building, designed by Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis in concrete brutalist style in the 1970s is Grade II listed.[36] The Whiteknights campus was voted one of the best green spaces in the United Kingdom for the seventh year running in the 2017 Green Flag People's Choice awards.[37]

London Road

[edit]The smaller London Road Campus is the original university site and is closer to the town centre of Reading, sited across from the Royal Berkshire Hospital. The London Road site is home to The Institute of Education – a major provider of teacher training in the UK.[38] The Institute moved to its new home in January 2012 after the campus was refurbished at a cost of £30 million.[25] The London Road site also plays host to the university graduation ceremonies twice a year, in the Great Hall.[39]

Greenlands

[edit]The Greenlands Campus, on the banks of the River Thames in Buckinghamshire. Once the home of William Henry Smith, son of the founder of WH Smith, and latterly the site of the Henley Management College, this campus became part of the university on 1 August 2008, with the merger of that college with the university's Business School to form the Henley Business School. The school's MBA and corporate learning offerings will be based at Greenlands, with undergraduate and other postgraduate courses being based at Whiteknights.[23]

Malaysia

[edit]An Asian campus at Iskandar, Malaysia was formally opened in February 2016.[40] It offers a range of professional programmes at foundation, undergraduate and postgraduate levels including the Henley Business School MBA.[41] First announced in October 2012, it is the university's first overseas campus. The project was overseen by Tony Downes.[42][43] Professor Wing Lam took over as Provost in May 2018 after the retirement of Tony Downes[44] and restructured the campus to enable it to focus on core professional disciplines that were aligned with the region's need for talent.[45]

Other sites

[edit]The former Bulmershe Court Campus in Woodley was the site of the former Bulmershe Teaching College, which merged with The University of Reading in 1989. The campus was sold in January 2014 as the university decided to concentrate its activity on its three other campuses. It had previously moved all teaching and research at Bulmershe either to Whiteknights or to London Road, and closed the student accommodation.

The university also owns 8.5 square kilometres (2,100 acres) of farmland in the nearby villages of Arborfield, Sonning and Shinfield. These support a mixed farming system including dairy cows, ewes and beef animals, and host research centres of which the flagship is the Centre for Dairy Research.

As part of the proposed Whiteknights Development Plan in Autumn 2007, the university proposed spending up to £250 million on its estates over 30 years, principally to focus academic activities onto the Whiteknights site.[46] The university also announced its intention to site some functions on the London Road site, and proposed a complete withdrawal from Bulmershe Court by 2012, which was accomplished.

Museums, libraries and botanical gardens

[edit]

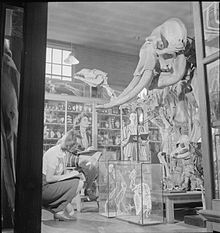

Reading University maintains four museums, the main campus library, a range of inter-departmental libraries, and a botanical garden. The largest and best known of these museums is the Museum of English Rural Life, which has recently relocated from a location on Whiteknights Campus to a site nearer the town centre next to the London Road Campus. The Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology, the Cole Museum of Zoology, the University of Reading Herbarium and the Harris Garden are all on the Whiteknights Campus. The Department of Typography and Graphic Communication holds a number of lettering, printing and graphic design collections[47] including those of Isotype, Ephemera, printing presses, Twentieth-century posters, non-Latin typefaces and the archive of partners Banks and Miles.[48]

The University Library at Whiteknights makes available over 1 million physical resources, as well as a range of electronic online resources, from 14,000 square metres of space across seven floors. The secondary site library at the university's Bulmershe campus closed in 2011 and its operative collections were transferred. There is also a library in the university's Meteorology department.

The library underwent refurbishment costing £40 million starting in 2016[49] and was re-opened in autumn 2019.[50] The redevelopment aimed to improve the energy efficiency of the building with the installation of new windows, cladding and roofing. New lifts, additional study seating capacity, a larger Library cafe with an outside seating area, more toilets (including disabled and gender-neutral provision) and card-access security barriers were also part of the refurbishment programme.[50]

Organisation and governance

[edit]Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Science

- School of Arts and Communication Design

- Department of Art

- Department of Film, Theatre and Television

- Department of Typography and Graphic Communication

- Institute of Education

- School of Humanities

- Department of Classics

- Department of History

- School of Law

- School of Literature and Languages

- Department of English Language and Applied Linguistics

- Department of English Literature

- Department of Languages and Cultures

- School of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics

- Department of Economics

- Department of Philosophy

- Department of Politics and International Relations

- International Study and Language Institute

Faculty of Life Sciences

- School of Agriculture, Policy and Development

- School of Biological Sciences

- School of Chemistry, Food and Pharmacy

- Department of Chemistry

- Food and Nutritional Sciences

- The Reading School of Pharmacy

- School of Psychology and Clinical Language Science

- Department of Clinical Language Sciences

- Department of Psychology

Faculty of Science

- School of Construction Management and Engineering

- School of Archaeology, Geography and Environmental Science

- Department of Archaeology

- Department of Geography and Environmental Science

- School of Mathematical, Physical and Computational Sciences

- Department of Mathematics and Statistics

- Department of Meteorology

- Department of Computer Science

Henley Business School

[edit]Henley Business School is a highly selective, top-ranking business school, among only 58 institutions worldwide to be granted Triple accreditation by the three largest and most influential business school accreditation associations: EQUIS, AMBA and the AACSB.[51] It includes several academic areas:

- Marketing and Reputation[52]

- Business Informatics, Systems and Accounting

- Leadership and Organisational Behaviours

- International Business and Strategy

- ICMA Centre[53]

- Real Estate and Planning

Graduate school

[edit]The university-wide Graduate School is a faculty providing training and a range of support for doctoral researchers and related staff across the other four faculties.

Governing bodies and roles

[edit]The university is nominally led by a chancellor, who is the titular head of the university and is normally a well-known public figure. The day-to-day chief executive role is the responsibility of the vice-chancellor, a full-time academic post. The senior management board of the university is headed by the vice-chancellor, assisted by a deputy-vice-chancellor, three pro-vice-chancellors, four deans and five heads of directorate. It is responsible for the day-to-day management of the university and meets fortnightly throughout most of the year.[54]

The senior management board reports to the university's Senate, the main academic administrative body. The senate has around 100 members and meets at least four times a year and advises on areas such as student entry, assessment and awards. Membership includes deans, heads and elected representatives of schools, as well as professional staff and students. The Senate in turn reports to the Council, which is the supreme governing body of the university, setting strategic direction, ensuring compliance with statutory requirements and approving constitutional changes. The Council meets four times a year and comprises a broad representation of lay members drawn from commercial, community and professional organisations.[54]

On 24 March 2016, it was announced that William Waldegrave was to be the new chancellor of Reading University.[55] Lord Waldegrave is the fourth Conservative politician to be appointed chancellor of the university, following Austen Chamberlain, Sir Samuel Hoare and Lord Carrington. Waldegrave's predecessor, Sir John Madejski is also a supporter of, and contributor to, the Conservative Party.

Finances

[edit]In the financial year ending 31 July 2024, Reading had a total income of £339.2 million (2022/23 – £321.9 million) and total expenditure of £257.2 million (2022/23 – £325.7 million).[56] Key sources of income included £198.8 million from tuition fees and education contracts (2022/23 – £186.9 million), £32 million from funding body grants (2022/23 – £36.5 million), £33.7 million from research grants and contracts (2022/23 – £34 million), £9.6 million from investment income (2022/23 – £7.4 million) and £4.1 million from donations and endowments (2022/23 – £4.9 million).[1]

At year end, Reading had endowments of £111.4 million (2023 – £101.9 million) and total net assets of £533.6 million (2023 – £453.2 million). It holds the thirteenth-largest endowment of any university in the UK.[1]

Between 2009 and 2010, the university was beset by controversy, with the closure of departments and job losses among staff.[19][20][21] The university lost 7.7% of its HEFCE funding in fiscal year 2010–2011.[57] In 2016 a move to reorganise the structure of Reading University provoked protests.[29]

Academic profile

[edit]Admissions

[edit]

|

New students entering the university in 2020 had an average of 129 points (the equivalent of ABB at A Level).[60] According to the 2023 Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide, approximately 13% of Reading's undergraduates come from independent schools.[61]

Reputation and rankings

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[62] | 35 |

| Guardian (2025)[63] | 35 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2025)[64] | 24= |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[65] | 401–500 |

| QS (2025)[66] | 172 |

| THE (2025)[67] | 201–250 |

Departments in the university have been awarded the biannual Queen's Anniversary Prize for Higher and Further Education five times: in 1998, in the Humanities, Social Sciences and Law category, for work on Shakespeare; in 2005, in the Environment category; in 2008, again in Humanities, Social Sciences and Law; in 2011, for "teaching and design applications in typography, through print and new technologies" in Typography & Graphic Communication; and in 2021, again in the category of Environment And Conservation, for "connecting communities with climate change" through "new modelling work on the interaction between the Earth’s climate and local weather systems, enabling the development of risk assessment, community preparedness and action to tackle climate change."[68]

Reading was ranked 35th in the UK amongst multi-faculty institutions for the quality (GPA) of its research[69] and 28th for its Research Power in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework.[70] In total, 98% of the university's research is labelled as 'internationally recognised', 78% as 'internationally excellent and 27% as 'world leading'.[71]

Its School of Agriculture Policy and Development was ranked top in the UK and 11th in the world, according to the QS classification of universities by subject.[72]

Reading has been highly ranked in meteorology and atmospheric science. In the 2024 Global Ranking of Academic Subjects, it was ranked 5th in the world for atmospheric science.[73] It was ranked 15th in the world for Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences by U.S. News & World Report in 2024[74] and 13th among global universities in atmospheric science in the 2024 SCImago Institutions Rankings.[75] It was ranked 2nd in the world in meteorology and atmospheric sciences by the Center for World University Rankings in 2017 (the most recent year subject rankings were published).[76]

Affiliated institutions

[edit]The Gyosei International College in the U.K. was established on property acquired from the University of Reading in 1989. The college, later renamed Witan International College, was acquired by the University of Reading in 2004.[77] Witan College closed in 2008.[78]

In 2009 the university partnered with the Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology to offer Chinese students courses taught by the department of chemistry.[79] In 2015 this was expanded to form the NUIST Reading Academy which currently offers six degree programs and enrolls nearly 400 students annually.[80][81]

Student life

[edit]Students’ Union

[edit]Reading University Students' Union (RUSU) is the affiliated student organisation which represents the students' interests. The university also has a number of Junior Common Rooms that are linked to the Students' Union. The Students' Union has been the launchpad for many successful careers including Penny Mordaunt (Former MP for Portsmouth North), who was the 1994–5 president of the Students' Union.

The Students' Union runs the student radio station. It broadcasts locally from the Whiteknights campus in university retail outlets and over an internet live stream on a full-time basis. The station was formed in 1997 and started broadcasting in 2001 on 1287AM and transferred to solely online in 2007. It also publishes the Spark, a newspaper aimed at the student population of the university, which is published fortnightly during term-time only and student television station RU:ON.

The union provides a free advice service to students, and facilitates over 160 different activities for students to get involved in.[82] The Students' Union building on Whiteknights Campus contains a 2500 capacity venue called 3sixty (recently renovated in 2018), with seven bars, and a number of retail outlets. The retail outlets include an Asian supermarket, a Starbucks and a hairdressers.

Halls and accommodation

[edit]

Student accommodation is provided in a number of halls of residence offering a mix of partially catered (19 meals per week) and self-catering accommodation, along with other self-catering accommodation. Following a major review the university is now proceeding with the integrated Halls and Catering Strategy, that will see several halls replaced as well as new ones created with social, catering & welfare facilities provided in hub areas.[83] Most of the halls of residence lie close to the northern campus periphery and in residential areas close by.

Wantage Hall is the second oldest purpose-built hall in England outside of Oxford and Cambridge, opening a year after Hulme Hall at the University of Manchester,[84] and is built in the style of an 'Oxbridge' college.

St. Andrews Hall closed in 2000 and is now the home of the Museum of English Rural Life.[85]

St. George's Hall and the Reading Student Village (renamed Benyon) are leased back to the university from UPP. The cost of leasing back the Student Village to the university, according to the university accounts, was £1.3 million in 2002–03 and £1.5 million for 2003–04.[citation needed]

In 2011 the management of the mature and international halls, Hillside and Martindale, was taken over by the "Estates management team", as was Bulmershe Hall in 2012, the sale of which was finalised in 2014.[86] In the same year the new Kendrick Halls were opened on the ground of halls which had not been in use for many years. These are not managed by the university.

Working with business

[edit]Reading hosts a number of private sector businesses on its campuses, either occupying dedicated buildings or in managed space at the Science & Technology Centre or Enterprise Hub.

Science & Technology Centre

[edit]The University of Reading Science & Technology Centre is situated on the eastern side of Whiteknights Campus. The Science & Technology Centre supports and accommodates technology companies from start-up through to larger SMEs.[87][88][89]

Notable companies currently or previously based at the Science & Technology Centre[90][91] include Reading Scientific Services Ltd.

Reading Enterprise Hub

[edit]Reading Enterprise Hub is a business incubator opened in 2003. The hub was jointly sponsored by the university and SEEDA, and sought to attract startup high tech companies, particularly those with interests in environmental technology, information technology, life sciences, and materials science.[92]

The hub was originally situated in World War II-era temporary office buildings on the university's Whiteknights campus. During the summer of 2008, the hub was demolished, along with the neighbouring former agriculture buildings, and the remaining tenants relocated to a building on the London Road campus. As of April 2010, a new Reading Enterprise Centre is being constructed on the hub's original site.[93]

Notable people

[edit]Notable alumni

[edit]Officers

[edit]Principals of University College, Reading

- Sir Halford John Mackinder (1892–1903)[12][94]

- William Macbride Childs (1903–1926)[12][95]

Chancellors of the University of Reading

- J. H. Benyon (1926–1935)[96]

- Sir Austen Chamberlain (1935–1937)[96]

- Sir Samuel Hoare (1937–1959)[96]

- Lord Bridges (1959–1969)[96]

- Sir Roger Makins (1970–1992)[96]

- Lord Carrington (1992–2007)[96][97]

- Sir John Madejski (2007–2016)[96][97]

- William Waldegrave (2016–2022)[98]

- Paul Lindley (2022–Present)[99]

Vice-Chancellors of the University of Reading

- William Macbride Childs (1926–1929)[95]

- Sir Franklin Sibly (1929–1946)[100]

- Sir Frank Stenton (1946–1950)[101]

- Sir John Wolfenden (1950–1963)[102]

- Sir Harry Raymond Pitt (1964–1978)[103]

- Ewan Page (1979–1993)[104][105]

- Sir Roger Williams (1993–2002)[106]

- Gordon Marshall (2003 – July 2011)[107][108]

- Tony Downes (acting; July 2011 – January 2012)[109]

- Sir David Bell (January 2012 – September 2018)[109][110]

- Robert Van de Noort (August 2018 – Present)[111][112]

Notable academics

[edit]- Stanislav Andreski – was a professor of Sociology at the University of Reading

- Malcolm Barber – Emeritus Professor of History, University of Reading

- Dianne Berry – Professor of Psychology and Dean of Postgraduate Research Studies at the University of Reading

- James Anthony Betts - inaugural Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Reading (1934-1963)

- Emily Black - Professor of Meteorology at the University of Reading and a senior research fellow in National Centre for Atmospheric Science (Climate)

- Humphry Bowen – Reader in Analytical Chemistry at the University of Reading

- Nicola Bradbury – Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Reading

- William de Burgh – Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Mark Casson – Professor of Economics, University of Reading[113]

- Susanne Clausen – Professor of Fine Art, University of Reading

- Francis Cole – Professor of Zoology, University of Reading

- Howard Colquhoun – Professor of Materials Chemistry, University of Reading

- John Cottingham – Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Neil Crosby – Professor of Real Estate, University of Reading

- Jonathan Dancy – Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Michael Drew – Professor of Chemistry, University of Reading

- Christopher Duggan – was Professor of Modern Italian History, University of Reading

- Antony Flew – was Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Rosa Freedman – Professor of law, conflict, and global development[114]

- Sir Terry Frost – was Professor of Fine Art, University of Reading

- Michael Fulford – Professor of Archaeology and Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the University of Reading

- Colin S. Gray – Professor of International Relations and Strategic Studies, University of Reading

- Edward Guggenheim – was a thermodynamicist and professor of chemistry at the University of Reading

- Andrew Gurr – was a professor of English at the University of Reading until his retirement and is a leading authority on Shakespeare

- Katherine Harloe - Professor of Classics, expert on classical reception, in particular the classicist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann

- Beatrice Heuser – Professor of International Relations, University of Reading

- Gustav Holst – former lecturer in Music at University College, Reading

- Brad Hooker – Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Harold Hopkins – was a professor of Applied Physical Optics at the University of Reading

- Sir Brian Hoskins – Professor of Meteorology, University of Reading and Director of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change, Imperial College London

- Vitaliy Khutoryanskiy – Professor of Formulation Science and Royal Society Industry Fellow

- Mary Lewis – Professor of Bioarchaeology, University of Reading

- Michael Lockwood – Professor of Space Environment Physics, University of Reading

- William Burley Lockwood – Professor of Germanic and Indo-European Philology 1968–1982

- J-P Mayer – Professor Emeritus, editor of the works of Alexis de Tocqueville and founder of the Tocqueville Research Centre at the university

- Roger W. Mills – Emeritus Professor of Finance, University of Reading

- Edith Morley – Professor of English, University College, Reading: the first woman appointed (1908) to a chair at a British university-level institution.[115]

- Helene Muri – Norwegian climate scientist

- Crispin St. J. A. Nash-Williams – was a professor of Mathematics at the University of Reading

- David S. Oderberg – Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Frank R. Palmer – Emeritus Professor of the Linguistic Science, University of Reading

- Richard Rado – was a professor of Mathematics at the University of Reading

- Peter Robinson – poet, poetry editor at Two Rivers Press, and Professor of English and American literature at the University of Reading

- Michael Schmitt – Professor of International Law, University of Reading

- Ted Shepherd – Grantham Professor of Climate Science, elected Fellow of the Royal Society

- Hugh Macdonald Sinclair – pioneer of human nutrition and visiting professor in Food Science at the University of Reading

- Keith Shine – Professor of Meteorology, University of Reading

- Jeremy Paul Edward Spencer - Professor of Molecular Nutrition, University of Reading

- Sir Frank Stenton – was a professor of History at the University of Reading

- Galen Strawson – Professor of Philosophy, University of Reading

- Percy and Annie Ure – husband and wife team. Percy was the first professor of classics at Reading and Annie was the curator of the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology

- Magdalen Dorothea Vernon – Professor of psychology, first woman to head the department

- Andrew Wallace-Hadrill – Director of the British School at Rome and professor of Classics, University of Reading

- Kevin Warwick – former Professor of Cybernetics, University of Reading

- Stuart Woolf - Reader in Italian from 1965 to 1974

See also

[edit]- Early Modern Research Centre (University of Reading)

- International Cocoa Quarantine Centre, a project of the university

- List of modern universities in Europe (1801–1945)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Annual Report and Financial Statements 2023–2024" (PDF). University of Reading. p. 64. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ "University of Reading Key Staff". University of Reading. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Professor Robert Van de Noort". University of Reading. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Who's working in HE?". www.hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ a b c "Where do HE students study? | HESA". hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ "University of Reading Wool Scarf". Reading University Students' Union. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ Reporters, Telegraph (31 July 2019). "University of Reading: a guide to the courses, rankings and student life". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Facts and figures". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b "University College, Reading". Reports for the year 1909-10 from those Universities and University Colleges in Great Britain which participate in the Parliamentary Grant for University Colleges. HMSO. 1911. p. 553.

- ^ a b c d "The University's History". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ "The University of Reading is 85 years old". University of Reading. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Corley, T.A.B. (2004). "Childs, William Macbride (1869–1939), educationist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32402. Retrieved 8 February 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Hospitium". readingabbeyquarter.org.uk. Reading Borough Council. 15 February 2018. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Campus Architecture". University of Reading. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "Statutory Instrument 1989 no. 408". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ "Official statement about the Physics Department on the University website". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Information page of Labour MP for Reading West, Martin Salter". Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Official Statement about University Senate vote from University website". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

- ^ a b "article concerning the confirmed closure of the Physics department". BBC News. 21 November 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ a b Melanie Newman, "Institutions draw up plans for closures and job losses", Times Higher Education, 19 February 2009

- ^ a b Melanie Newman, "Alarm grows as jobs to go at four more institutions", Times Higher Education, 26 March 2009

- ^ "World-class business school to be created as University of Reading merges with Henley Management College". University of Reading. 9 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Briefing News Update – Henley Business School". University of Reading. Summer 2008.

- ^ Fearn, Hannah (11 September 2009). "Reading plans restructuring". Times Higher Education.

- ^ a b "Welcome to your new home – Institute of Education". The University of Reading. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "University announces £30 million development of historic London Road campus". University of Reading. 10 December 2009. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Partners – UTC". Utcreading.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "High-tech education at Reading's first technical college". Reading Chronicle. 17 September 2013. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Hyde, Nathan. "Cost-cutting review slammed by University of Reading student". getreading. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Hyde, Nathan (22 March 2016). "University of Reading vice chancellor faces vote of no confidence". getreading. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ "'No confidence' in University of Reading vice-chancellor". BBC News. 14 April 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Andrew McGettigan, Richard Adams (9 February 2019). "Reading University in crisis amid questions over £121m land sales". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Adams, Luke (9 February 2019). "University of Reading expected to cut jobs due to challenging financial times". Reading Chronicle. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "UEB Response to RUSU Open Letter" (PDF). University of Reading. 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Campus life for students". University of Reading. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ De Castella, Tom (8 July 2019). "Reading Uni shelves Hawkins\Brown's 'Lego Building' overhaul". Architects' Journal. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "University of Reading". University of Reading. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Smithers, Alan; Bungey, Mandy-D. "The Good Teacher Training Guide 2017" (PDF). University of Buckingham. Centre for Education and Employment Research. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "University of Reading". University of Reading.

- ^ "University of Reading's £25m Malaysia campus officially opens". BBC News Online. 25 February 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "The University of Reading Malaysia – about us". The University of Reading Malaysia. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "University of Reading Malaysia appoints Provost". reading.ac.uk. 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ "University of Reading Malaysia". reading.ac.uk.

- ^ "Tony Downes to retire; Wing Lam appointed new UoRM Provost". archive.reading.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Changes at University of Reading Malaysia - University of Reading". www.reading.ac.uk.

- ^ "Whiteknights development plan" (PDF). University of Reading. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Collections and archives – Department of Typography & Graphic Communication". www.reading.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Alexander, James (4 April 2002). "Colin Banks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "University of Reading". University of Reading. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b Redrup, Rachel. "Library open following major refurbishment". University of Reading. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "Accreditations". Henley Business School. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Kind (2 June 2018). "- Henley Business School". Henley Business School. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Department of Finance associated with ICMA Centre

- ^ a b "Governance of the University of Reading". University of Reading. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "Lord Waldegrave named as Reading University chancellor", BBC News, 24 March 2016

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Exeter Financial Statement 23/24was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Melanie Newman, "Teaching and research escape 9% grant cut", Times Higher Education, 18 March 2010

- ^ a b "UCAS Undergraduate Sector-Level End of Cycle Data Resources 2024". ucas.com. UCAS. December 2024. Show me... Domicile by Provider. Retrieved 7 February 2025.

- ^ "2024 entry UCAS Undergraduate reports by sex, area background, and ethnic group". UCAS. 7 February 2025. Retrieved 7 February 2025.

- ^ a b "University League Tables entry standards 2024". The Complete University Guide.

- ^ "The Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide 2023". The Good University Guide. London. Retrieved 16 February 2023.(subscription required)[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Complete University Guide 2025". The Complete University Guide. 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Guardian University Guide 2025". The Guardian. 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Good University Guide 2025". The Times. 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2024". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 15 August 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. 4 June 2024.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings 2025". Times Higher Education. 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Winners archive".

- ^ "Research Excellence Framework results 2014" (PDF).

- ^ "REF 2014 results". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Research facts and figures". The University of Reading. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings by Subject 2014 – Agriculture & Forestry". QS.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's Global Ranking of Academic Subjects". www.shanghairanking.com.

- ^ "Best Global Universities for Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ "University Overall Rankings - Atmospheric Science 2024". www.scimagoir.com.

- ^ "Rankings by Subject - 2017 | CWUR | Center for World University Rankings". cwur.org.

- ^ "The University of Reading and Witan International College." (Archive) University of Reading. 6 August 2004. Retrieved on 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Witan International College." (Archive) University of Reading. Retrieved on 9 January 2014.

- ^ "About NUIST". University of Reading. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Reading academy". Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "NUIST Reading Academy". University of Reading. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Societies". www.rusu.co.uk.

- ^ "Halls Redevelopment Information". University of Reading. p. 1. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Hulme Hall, Oxford Place, Victoria Park, Rusholme, Manchester - Building | Architects of Greater Manchester".

- ^ "The History of St. Andrew's Hall". Online Exhibitions. The Museum of English Rural Life. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "University finalises sale of Bulmershe campus". University of Reading. 21 January 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Science & Technology Centre – Business Zone". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ "University of Reading Science and Technology Centre and Enterprise Hub". UKSPA. Archived from the original on 26 November 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ "Science Parks in Europe". UNESCO. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ "Science & Technology Centre – Companies". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 23 March 2005. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ "Science & Technology Centre – Companies". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "Reading Enterprise Hub". University of Reading. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ "Facilities for Business at the University of Reading". University of Reading. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Ian Macrae, "The making of a university, the breakdown of a movement: Reading University Extension College to The University of Reading, 1892–1925", Journal International Journal of Lifelong Education, Volume 13, Issue 1 January 1994, pages 3–18

- ^ a b "University of Reading Bulletin (16 March 2006)" (PDF). University of Reading. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Reading welcomes its new chancellor". Bulletin. University of Reading. 17 January 2008. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b "Football boss made uni chancellor". BBC. 11 July 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "University of Reading selects new Chancellor". 24 March 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ "Graduation reflections by Chancellor Paul Lindley". 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Halls Booklet" (PDF). University of Reading. p. 12. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "University of Reading Bulletin (20 November 2008)". University of Reading. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ "Papers of Lord Wolfenden". University of Reading. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Sewell, Michael (2 February 2006). "Tribute to Sir Harry Raymond Pitt, F.R.S." (PDF). Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ "Apply again, funding council tells universities". Times Higher Education Supplement. TSL Education Limited. 21 July 1995. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ "First Vice-Chancellor for computer profession" (PDF). The Computer Journal. Oxford Journals / Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ "Professor Sir Roger Williams". University of Glamorgan. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Professor Gordon Marshall". University of Reading. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "Farewell Vice-Chancellor". University of Reading. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Introducing our new Vice-Chancellor". University of Reading. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Vice-Chancellor, Sir David Bell, to leave the University of Reading". University of Reading. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Vice-Chancellor, Sir David Bell, to leave University of Reading". University of Reading. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "New vice-chancellor for University of Reading". The Reading Chronicle. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "Professor Mark Casson – University of Reading". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Professor Rosa Freedman - University of Reading". Reading.ac.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ Law, Cheryl (2004). "Morley, Edith Julia (1875–1964)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/48617. Retrieved 14 February 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

[edit]- Official website

- University of Reading at the Wayback Machine (archive index)