Uganda Railway

| |

| Company type | Government-owned corporation |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1895 |

| Defunct | 1929 |

| Successor | Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours East African Railways & Harbours |

Key people | Sir George Whitehouse |

| History of Kenya |

|---|

|

|

|

The Uganda Railway was a metre-gauge railway system and former British state-owned railway company. The line linked the interiors of Uganda and Kenya with the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa in Kenya. After a series of mergers and splits, the line is now in the hands of the Kenya Railways Corporation and the Uganda Railways Corporation.

Construction

[edit]

The official approach, British and local, to both slavery and free porter labour included a genuine belief that the man doing the work had real interests which deserved concern and protection. No such concern was evident among parliamentarians, missionaries or administrators for those at work on the construction of the Uganda Railway. It was decided to build the railway as quickly as possible; its construction was viewed almost as a military attack—casualties were inevitable and might be large if the objective were to be attained and momentum not lost.[1]

Background

[edit]Before the railway's construction, the Imperial British East Africa Company had begun the Mackinnon-Sclater road, a 970-kilometre (600 mi) ox-cart track from Mombasa to Busia in Kenya, in 1890.[2]

In July 1890, Britain was party to a series of anti-slavery measures agreed at the Brussels Conference Act of 1890. In December 1890, a letter from the Foreign Office to the treasury proposed constructing a railway from Mombasa to Uganda to disrupt the traffic of slaves from its source in the interior to the coast.[3]

With steam-powered access to Uganda, the British could transport people and soldiers to ensure dominance of the African Great Lakes region.[4]

In December 1891 Captain James Macdonald began an extensive survey which lasted until November 1892. At the time there was only one caravan route across the length of the country, forcing Macdonald and his party to march 4,280 miles (6,890 km) across unknown routes with limited supplies of water or food. The survey led to the first general map of the region.[5]

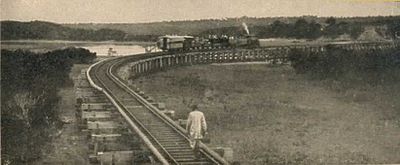

The Uganda Railway was named after its ultimate destination, for its entire original 1,060-kilometre (660 mi) length actually lay in what would become Kenya.[6] Construction began at the port city of Mombasa in British East Africa in 1896 and finished at the line's terminus, Kisumu, on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, in 1901.[2]

Engineering

[edit]

The railway is 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge[7] and virtually all single-track with passing loops at stations. 200,000 individual 9-metre (30 ft) rail-lengths and 1.2 million sleepers, 200,000 fish-plates, 400,000 fish-bolts and 4.8 million steel keys plus steel girders for viaducts and causeways had to be imported from India, necessitating the creation of a modern port at Kilindini Harbour in Mombasa. The railway was a huge logistical achievement and became strategically and economically vital for both Uganda and Kenya. It helped to suppress slavery, by removing the need for humans in the transport of goods.[8]

Management

[edit]| Uganda Railway Act 1896 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to make provision for the Construction of a Railway in Africa, from Mombasa to the Victoria Nyanza, through the Protectorates of Zanzibar, British East Africa, and Uganda. |

| Citation | 59 & 60 Vict. c. 38 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 14 August 1896 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Statute Law Revision Act 1950 |

Status: Repealed | |

In August 1895, a bill was introduced at Westminster, becoming the Uganda Railway Act 1896 (59 & 60 Vict. c. 38), which authorised the construction of a railway from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria.[9] The man tasked with building the railway was George Whitehouse, an experienced civil engineer who had worked across the British Empire. Whitehouse acted as the Chief Engineer between 1895 and 1903, also serving as the railway's manager from its opening in 1901. The consulting engineers were Sir Alexander Rendel of Sir A. Rendel & Son and Frederick Ewart Robertson.[10]

Workers

[edit]Nearly all the workers involved on the construction of the line came from British India. An agent was appointed in Karachi responsible for recruiting coolies, artisans and subordinate officers and a branch office was located in Lahore, the principal recruiting centre. Workers were sourced from villages in the Punjab and sent to Karachi on specially chartered steamers belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company.[11] Shortly after recruitment began, a plague broke out in India, seriously delaying the advancement of the railway. The Government of India only permitted recruitment and emigration to resume on the creation of a quarantine camp at Budapore, financed by the Uganda Railway, and where recruits were required to spend fourteen days in quarantine before departure.[11]

A total of 35,729 coolies and artisans were recruited along with 1,082 subordinate officers, totalling 36,811 persons.[12] Each coolie signed a contract for three years at twelve rupees per month with free rations and return passage to their place of enlistment. They received half-pay when in hospital and free medical attendance.[12] Recruitment continued between December 1895 and March 1901, and the first coolies began to return to India after their contracts ended in 1899. 2,493 workers died during the construction of the railway between 1895 and 1903 at a rate of 357 annually.[12] While most of the surviving Indians returned home, 6,724 decided to remain after the line's completion, creating a community of Indians in East Africa.[6]

Law and order

[edit]To maintain law and order, the railway instituted a police department. The force was uniformed and drilled and armed with Martini-Henry rifles.[13] The force was composed of Indians and two officers were lent by the Indian government to drill and superintend the force. A maximum of 400 constables were recruited, and the force was handed over to the Protectorate government on completion of the railway.[13]

Resistance

[edit]At the turn of the 20th century, the railway construction was disturbed by the resistance by Nandi people led by Koitalel Arap Samoei. He was killed in 1905 by Richard Meinertzhagen, ending the Nandi resistance.[14]

Tsavo man-eating lions

[edit]The incidents for which the building of the railway may be most noted are the killings of a number of construction workers in 1898, during the building of a bridge across the Tsavo River. Hunting mainly at night, a pair of maneless male lions stalked and killed at least 28 Indian and African workers – although some accounts put the number of victims as high as 135.[15]

Lunatic Express

[edit]The Uganda Railway faced a great deal of criticism in Parliament, with many parliamentarians decrying it as exorbitantly expensive. Whilst the concept of cost-benefit analysis did not exist in public spending in the Victorian Era, the huge capital sums of the project nevertheless made many sceptical of the value of the investment. This, coupled with the fatalities and wastage of the personnel constructing it through disease, tribal activity, and hostile wildlife led the Uganda Railway to be dubbed a Lunatic Line:

What it will cost no words can express,

What is its object no brain can suppose,

Where it will start from no one can guess,

Where it is going to nobody knows,

What is the use of it, none can conjecture,

What it will carry, there is none can define,

And in spite of George Curzon's superior lecture,

It is clearly naught but a lunatic line.— Henry Labouchère, MP, [16]

Political resistance to this "gigantic folly", as Henry Labouchère called it,[17] surfaced immediately. Such arguments along with the claim that it would be a waste of taxpayers' money were easily dismissed by the Conservatives. Years before, Joseph Chamberlain had proclaimed that, if Britain were to step away from its "manifest destiny", it would by default leave it to other nations to take up the work that it would have been seen as "too weak, too poor, and too cowardly" to have done itself.[18] Its cost has been estimated by one source at £3 million in 1894 money, which is more than £170 million in 2005 money,[19] and £5.5 million or £650 million in 2016 money by another source.[20]

Because of the wooden trestle bridges, enormous chasms, prohibitive cost, hostile tribes, men infected by the hundreds by diseases, and man-eating lions pulling railway workers out of carriages at night, the name "Lunatic Line" certainly seemed to fit. Winston Churchill, who regarded it "a brilliant conception", said of the project: "The British art of 'muddling through' is here seen in one of its finest expositions. Through everything—through the forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway."[21]

The modern term Lunatic Express was coined by Charles Miller in his 1971 The Lunatic Express: An Entertainment in Imperialism. The term The Iron Snake[22] comes from an old Nandi prophecy by Orkoiyot Kimnyolei: "An iron snake will cross from the lake of salt to the lands of the Great Lake to quench its thirst.."[23]

Extensions and branches

[edit]

Disassembled ferries were shipped from Scotland by sea to Mombasa and then by rail to Kisumu where they were reassembled and provided a service to Port Bell and, later, other ports on Lake Victoria (see section below). An 11-kilometre (7 mi) rail line between Port Bell and Kampala was the final link in the chain providing efficient transport between the Ugandan capital and the open sea at Mombasa, more than 1,400 km (900 mi) away.

Branch lines were built to Thika in 1913, Lake Magadi in 1915, Kitale in 1926, Naro Moro in 1927 and from Tororo to Soroti in 1929. In 1929 the Uganda Railway became Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours (KURH), which in 1931 completed a branch line to Mount Kenya and extended the main line from Nakuru to Kampala in Uganda. In 1948 KURH became part of the East African Railways Corporation, which added the line from Kampala to Kasese in western Uganda in 1956.[24] and extended to it to Arua near the border with Zaïre in 1964.

Inland shipping

[edit]Lake Victoria

[edit]Almost from its inception the Uganda Railway developed shipping services on Lake Victoria. In 1898 it launched the 110 ton SS William Mackinnon at Kisumu, having assembled the vessel from a "knock down" kit supplied by Bow, McLachlan and Company of Paisley in Scotland. A succession of further Bow, McLachlan & Co. "knock down" kits followed. The 662 ton sister ships SS Winifred and SS Sybil (1902 and 1903), the 1,134 ton SS Clement Hill (1907) and the 1,300 ton sister ships SS Rusinga and SS Usoga (1914 and 1915) were combined passenger and cargo ferries. The 812 ton SS Nyanza (launched after Clement Hill) was purely a cargo ship. The 228 ton SS Kavirondo launched in 1913 was a tugboat. Two more tugboats from Bow, McLachlan were added in 1925: SS Buganda and SS Buvuma.[25][26]

Lake Kyoga, Lake Albert and the Nile

[edit]The company extended its steamer service with a route across Lake Kyoga and down the Victoria Nile to Pakwach at the head of the Albert Nile. Its Lake Victoria ships were unsuitable for river work so it introduced the stern wheel paddle steamers PS Speke (1910)[27] and PS Stanley (1913)[27] for the new service. In the 1920s the company added PS Grant (1925)[27] and the side wheel paddle steamer PS Lugard (1927).[27]

Safari tourism

[edit]

As the only modern means of transport from the East African coast to the higher plateaus of the interior, a ride on the Uganda Railway became an essential overture to the safari adventures which grew in popularity in the first two decades of the 20th century. As a result, it usually featured prominently in the accounts written by travelers in British East Africa. The rail journey stirred many a romantic passage, like this one from former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who rode the line to start his world-famous safari in 1909:

The railroad, the embodiment of the eager, masterful, materialistic civilization of today, was pushed through a region in which nature, both as regards wild man and wild beast, does not differ materially from what it was in Europe in the late Pleistocene.[28]

Passengers were invited to ride a platform on the front of the locomotive from which they might see the passing game herds more closely. During Roosevelt's journey, he claimed that "on this, except at mealtime, I spent most of the hours of daylight."

Current status

[edit]

After independence, the railways in Kenya and Uganda fell into disrepair. In summer 2016, a reporter for The Economist magazine took the Lunatic Express from Nairobi to Mombasa. He found the railway to be in poor condition, departing 7 hours late and taking 24 hours for the journey.[20] The last metre-gauge train between Mombasa and Nairobi made its run on 28 April 2017.[29] The line between Nairobi and Kisumu near the Kenya–Uganda border has been closed since 2012.[30]

From 2014 to 2016, the China Road and Bridge Corporation built the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) parallel to the original Uganda Railway. Passenger service on the SGR was inaugurated on 31 May 2017. The metre-gauge railway is still used to transport passengers between the new SGR Nairobi Terminus and the old metre-gauge train station in Nairobi city centre.

Research has shown that expectations and hopes for the transformations that the Uganda railway would bring about are similar to contemporary visions about the changes that would happen once East Africa became connected to high-speed fibre-optic broadband.[31]

In popular culture

[edit]

A documentary on the construction of the line, The Permanent Way, was made in 1961. John Halkin's 1968 novel, Kenya, focuses on the construction of the railway and its defence during the First World War. The construction also serves as the backdrop to the novel Dance of the Jakaranda (Akashic Books, 2017) by Peter Kimani, and appears early in the novel A History of Burning by Janika Oza (2023).

The Tsavo man-eating lions at Tsavo feature in a factual account by Patterson's 1907 autobiographical book The Man-eaters of Tsavo. They are part of the plot of the 1956 film Beyond Mombasa, The Ghost and the Darkness in 1996, and Chander Pahar, a 2013 Bengali movie based on the 1937 novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay.

Several other films have featured the Uganda Railway, including Bwana Devil, made in 1952. In addition, the 1985 film Out of Africa utilizes its railway equipment in several scenes, albeit out of place.

See also

[edit]- Kenya Railways Corporation

- MacKinnon-Sclater road

- Rail transport in Kenya

- Transport in Uganda

- Uganda Railways Corporation

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Clayton & Savage 1975, pp. 10–1.

- ^ a b Ogonda 1992, p. 131.

- ^ Whitehouse 1948, p. 5

- ^ Ogonda & Onyango 2002, p. 223–4.

- ^ Whitehouse 1948, p. 2

- ^ a b Wolmar 2009, p. 182.

- ^ Treves, Frederick (1910). Uganda for a holiday. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 57. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ^ Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 601–606.

- ^ Whitehouse 1948, p. 3.

- ^ Whitehouse 1948, p. 15.

- ^ a b Whitehouse 1948, p. 7

- ^ a b c Whitehouse 1948, p. 8

- ^ a b Whitehouse 1948, p. 10

- ^ "End of Lunatic Express". The East African. 21 September 2009.

- ^ "Man eating lions – not (as) many dead". Railway Gazette International. 27 November 2009. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010.

- ^ Muiruri, Peter (31 May 2017). "End of road for first railway that defined Kenya's history". The Standard.

- ^ Henry Labouchère (30 April 1900). "UGANDA RAILWAY [CONSOLIDATED FUND]. HC Deb vol 82 cc288-335". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

I am opposed entirely to this sort of railway in Africa, and I have been opposed to this railroad from the very commencement because it is a gigantic folly. . . . This railroad has been, from the very first commencement, a gigantic folly.

- ^ Joseph Chamberlain (1 June 1894). "CIVIL SERVICES AND REVENUE DEPARTMENTS ESTIMATES, 1894–5: CLASS V. HC Deb vol 25 cc181-270". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "Currency converter". The National Archives. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ a b Knowles, Daniel (23 June 2016). "The lunatic express". The Economist. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Churchill 1909, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Hardy 1965.

- ^ Matson 2009.

- ^ "Investing in Uganda's Mineral Sector" (PDF). Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Cameron, Stuart; Asprey, David; Allan. "SS Buganda". Clyde-built Database. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ Cameron, Stuart; Asprey, David; Allan, Bruce. "SS Buvuma". Clyde-built Database. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Cambridge University Library: Royal Commonwealth Society Library, Mombasa and East African Steamers, Y30468L". Janus. Cambridge University Library.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore, 1909, African Game Trails, Charles Scribner's Sons, page 2

- ^ Ruthi, William (8 May 2017). "Last ride on the Lunatic Express". Daily Nation.

- ^ "Inter-City". Rift Valley Railways. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Graham, Mark; Andersen, Casper; Mann, Laura (15 December 2014). "Geographical imagination and technological connectivity in East Africa". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 40 (3): 334–349. doi:10.1111/tran.12076. ISSN 0020-2754.

Bibliography

[edit]- Amin, Mohamed; Willetts, Duncan; Matheson, Alastair (1986). Railway Across The Equator: The Story of the East African Line. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 0370307747.

- Boyles, Denis (1991). Man Eaters Motel and other stops on the railway to nowhere: an East African traveller's nightbook, including a summary history of Zanzibar and an account of the slaughter at Tsavo : together with a sketch of life in Nairobi and at Lake Victoria, a brief and worried visit to the Ugandan border, and a survey of angling in the Aberdares. New York: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 039558082X.

- Chao, Tayiana (28 October 2014). "The Lunatic Express – A photo essay on the Uganda railway". The Agora. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Churchill, Winston Spencer (1909) [1908]. My African Journey. Toronto: William Briggs. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Clayton, Anthony; Savage, Donald C. (1975). Government and Labour in Kenya, 1895–1963. London: Routledge.

- Hamshere, C. E. (March 1968). "The Uganda Railway". History Today. 18 (3): 188–195.

- Hardy, Ronald (1965). The Iron Snake. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Hill, M. F. (1961). Permanent Way. Vol. 1: The story of the Kenya and Uganda Railway (2nd ed.). Nairobi: East African Railways & Harbours. OCLC 776735246.

- Kinuthia, Helen. "The Iron Snake, History of the Kenyan Railways". Haligonian Investment Limited. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- D., Mannix (1954). "R.O. Preston of the Lunatic Line". In Hunter, J. A.; Mannix, D. (eds.). African Bush Adventures. Hamish Hamilton.

- Matson, Alfred T. (2009) [1993]. Nandi Resistance to British Rule: The Volcano Erupts. Nairobi: Transafrica Press. ISBN 978-9966-940-18-6.

- Mills, Stephen; Yonge, Brian (2012). A Railway to Nowhere: The Building of the Lunatic Line 1896-1901. Nairobi: Mills Publishing. ISBN 9789966709431.

- Odongo, Waga (12 December 2013). "How 'Lunatic Line' shaped Kenya and transformed the region". Daily Nation. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Ogonda, Richard T. (1992). "Transport and Communications in the Colonial Economy". In Ochieng', W. R.; Maxon, R. M. (eds.). An Economic History of Kenya. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. pp. 129–146. ISBN 978-9966-46-963-2.

- Ogonda, Richard T.; Onyango, George M. (2002). "Development of Transport and Communication". In Ochieng', William Robert (ed.). Historical Studies and Social Change in Western Kenya. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. pp. 219–231. ISBN 978-9966-25-152-7.

- Otte, T. G.; Neilson, Keith, eds. (2012). Railways and International Politics: Paths of Empire, 1848-1945. Military History and Policy. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415651318.

- Patience, Kevin (1976), Steam in East Africa: a pictorial history of the railways in East Africa, 1893-1976, Nairobi: Heinemann Educational Books (E.A.) Ltd, OCLC 3781370, Wikidata Q111363477

- Patterson, J. H. (2013) [First published 1908]. The Man-Eaters of Tsavo: And Other East African Adventures. New York: Skyhorse. ISBN 9781620874066.

- Preston, R. O. (1947). The Genesis of Kenya Colony: Reminiscences of an early Uganda railway construction pioneer. Nairobi: Colonial Printing Works. OCLC 3652501.

- Pringle, Patrick; Hill, Mervyn F. (1970) [First published 1954]. The Story of a Railway (New ed.). London: Evans Brothers Ltd. ISBN 0237288559.

- Ramaer, Roel (1974). Steam Locomotives of the East African Railways. David & Charles Locomotive Studies. Newton Abbot, North Pomfret: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-6437-6. OCLC 832692810. OL 5110018M. Wikidata Q111363478.

- Ramaer, Roel (2009). Gari la Moshi: Steam Locomotives of the East African Railways. Malmö: Stenvalls. ISBN 978-91-7266-172-1. OCLC 502034710. Wikidata Q111363479.

- Robinson, Neil (2009). World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. Volume 7: North, East and Central Africa. Barnsley, UK: World Rail Atlas Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5.

- Sood, Satya V. (2007). Victoria's Tin Dragon: a railway that built a nation. Cambridge, England: Vanguard Press. ISBN 9781843862741.

- Wolmar, Christian (2009). Blood, Iron & Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 9781848871700.

- Whitehouse, G. C. (March 1948). "The Building of the Kenya and Uganda Railway". The Uganda Journal. 12 (1). Kampala: The Uganda Society: 1–15.

External links

[edit]- History of the Uganda Railway

- 1⁄4 scale replica of EAR 31 class steam locomotive "Uganda" at Stapleford Miniature railway in the UK

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936), "Through desert and jungle", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 193–199 illustrated description of the Uganda railway